New series: Sitting, standing, and walking

- Introduction

- Physical deterioration

- Treadmill desks

- Frequent changes in posture and position

- Balance boards

- Yoga ball

- The anti-fatigue mat

- Constant rotation

- Challenging culture and expectations

- Links to products

- References

Introduction

In Get Up! Why your chair is killing you and what you can do about it, James Levine, MD, says that 86% of people spend 13 hours a day sitting, and 68% of them hate it. He says sitting is the culprit behind many physical ailments, contributing to diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and more. Levine pioneered the treadmill desk and says that the solution is simply to stand up and move around more frequently. I’ll get more into the details in later sections, but for now, I wanted to simply introduce the new series.

Beyond the dislike of sitting, why this topic? I like focusing on projects that involve a specific action of some kind. In my Journey away from smartphones series, that action involved first abandoning my smartphone and later, after reintroducing it, paring back its apps and functionality until it was no longer addictive. In this series, I plan to minimize my office chair and spend an equal amount of time standing as much as sitting. I’m aware of the challenges of giving up so much chair time, but my hope is that the changes will be worth it.

Physical deterioration

Although sitting isn’t unique to tech careers, sitting tends to go hand-in-hand with working on computers. As computers become more pervasive across all jobs, more of us are sitting the majority of the time. Productivity itself seems to involve sitting for long periods of still focus in front of the screen. Long-term sitting is not without effects on our bodies. Levine says:

The cost [of sitting] is too great; for every hour we sit, two hours of our lives walk away—lost forever. The list of health consequences is an alphabet soup of life’s torments. A is for arthritis, B is for blood pressure, C is for cancer, D is for diabetes … and so it goes. But what I have learned is that it is not these health consequences that hurt people the most. Sedentary living etches away at our very essence. The spring in our step has vanished. We sit in our cubicles alone, blue and sad. Our chairs have become islands of isolation. (1)

In other words, sitting doesn’t just lead to bodily impact but also affects our spirits. I’ll get into both of these topics later. But first, let me set up a bit more context about why this topic interests me. Physically, I’m in decent health. My blood sugar and blood pressure are a little high but not in danger zones. I could lose a good chunk of “Dad” weight as well. My lower back tends to hurt after sitting too much, caused in part by a herniated disc from a basketball injury 15+ years ago. Consequently, I often slouch in my chair. My right calf muscle tends to get strained every time I start playing serious basketball, which has compelled me to walk and bike more as an alternative. I’ve twisted my right ankle so many times, its ligaments are permanently loose. In sum, at 47 years of age, I know that I’m no spring chicken anymore, and I need to start taking better care of my body.

In A Writer’s Reflections on Turning 80, writer Jane Brody says that for the first 50 years of your life, your body can rebound no matter what you do to it. But after 50, it’s up to you. She writes:

Assuming you don’t smoke, which was my husband’s undoing, Nature will usually take pretty good care of you for about half a century. Thereafter, it’s up to you.

Without regular exercise, you can expect to experience a loss of muscle strength and endurance, coordination and balance, flexibility and mobility, bone strength and cardiovascular and respiratory function. In other words, a sedentary lifestyle is a recipe for chronic disease and decline.

I’m approaching that 50-year mark. If I don’t change course now, my body will continue to decline. I often see my teenage children sitting at desks or at the table doing homework, and I tell them, Your back might not feel it now, but give yourself 20 years sitting all day at a corporate desk and see how your back feels. I have a growing hunch that many of my physical ailments might be connected to extensive sitting. Even when I do regular calf exercises to strengthen my calves, when I follow the exercise with hours of sitting, I can almost feel the muscles disengaging again, atrophying by the hour.

In Sitting Kills, Moving Heals, Joan Vernikos, a former director of NASA’s Life Sciences Division, explains that sitting is akin to the effects astronauts experience in weightless space. She compares the impact of long-term sitting to the detrimental effects of being in space without gravity forcing their muscles to stabilize and exert force:

… we do not yet know of the ways our body senses gravity and what all the various characteristics of gravity are. However, we do know gravity pulls down to the center of the hearth, and it exerts its maximum effect when we stand up. We also know that sitting largely counteracts the beneficial effects of gravity. (31)

Without the benefits of gravity, astronauts’ physical bodies decline rapidly, not just their muscles but also bone density, blood pressure, brain, and more. She says:

We have always considered gravity as the foe that drags us down and dreamed of how liberating it would be to float in the weightlessness of space! But when astronauts traveled away from Earth’s gravitational pull, those of us at NASA who were monitoring their physical health were in for quite a shock. The absence of gravity for even a few days accelerated the astronauts’ physical degeneration. We found changes in their bodies of the kind that we typically associate with aging. Could it be that living without the downward pull of gravity was actually detrimental? We observed merely returning to their active lives on Earth, the astronauts could quickly be restored to full fitness. It became obvious that gravity is a greater contributor to good health than anyone has previously thought. We discovered that living without gravity is like being immobilized, since the leg muscles, bones, and the brain and spinal programs that regulate our movements are no longer needed and atrophy. Nothing speeds up brain atrophy like immobilization. And here we are, an entire population voluntarily immobilizing itself with its sedentary, comfort-oriented lifestyle. Gravity can’t help us when we’re sitting! (xi)

In other words, despite the fantasies we might have of floating in space, putting ourselves into gravity-less environments wreaks havoc on our bodies, speeding atrophy akin to advanced aging. It’s the equivalent of immobilizing ourselves long-term. Sitting is a position that seeks to skirt gravity and drives the rate of atrophy.

Vernikos says some of the astronauts have gone jogging a couple of days after they returned to earth, only to end up with a muscle injury, much like what happens to athletes without proper training. One astronaut who spent 2.5 hours of intense exercise a day nearly every day during a 152-day space mission said that upon returning, he “needed several weeks back on Earth to feel normal” (18). Imagine going to the gym 2.5 hours a day, doing intense physical exercise and weight training, only to watch your body continue to atrophy and get weaker and weaker. I feel that way about sitting in my chair; even when I go to the gym and run a couple of miles on the treadmill, it doesn’t reverse the atrophying effects of long-term sitting.

Both Vernikos and Levine don’t recommend going to the gym more to counteract the effects of sitting. They say that if you go to the gym for 30 minutes a day, it’s not enough to counter the other 23.5 hours spent sitting or lying down. Instead, they recommend frequent, small movements in a continuous way, like walking on a treadmill at 1 mph while working, or frequently changing posture. The answer isn’t standing all day, they say, but changing positions for much of the day in ways that activate your stabilizer muscles.

Treadmill desks

In my initial efforts to get up from my chair more, I experimented with working from a treadmill desk. Levine describes how he pioneered one of the first treadmill desks, along with wearables to measure movement. Treadmill desks are the solution Levine envisions to solve the problems of sitting. I’d always hated just standing at my desk. I wondered, could a treadmill be more tolerable than a basic standing position? I decided to experiment.

At my work, there are actually a couple of treadmill desks across the campus, so I decided to try them out. The first treadmill desk didn’t rise high enough. I’m 6’2”, but I wouldn’t consider myself “tall.” Even so, mechanized desks that can adjust the height at a push of a button tend to max out at a low-ish height. (I assume it’s challenging engineering-wise to maintain stability when the desks’ legs are fully extended.)

A good ergonomic position when typing is to have your elbows bent at a right angle, but since the desk didn’t rise high enough, I had to add 2 reams of paper and a few paper notebooks to elevate the keyboard. I also added 3 reams of paper before the raised keyboard so that my forearms could rest a bit on the desk, similar to the posture when sitting. As hacky as this sounds, using paper reams to elevate the desk height seemed to work well enough, and I started a slow walk at 0.7 mph.

One glaring detail that Levine doesn’t address in his treadmill desk solution is the challenge of working while standing, especially moving slowly. I initially thought it would be nearly impossible, especially typing, but actually, at 0.7 mph, it wasn’t. I could function at least at 90% efficiency or more. With more practice, I grew more accustomed to typing while walking. Sometimes my legs would get into an automaton-like cadence.

I thought perhaps all treadmill desks were similarly height-challenged, but I soon tracked down the location of the other treadmill desk (in another building) on my campus and found that it could rise another foot. This extra height was all I needed, and now the paper reams weren’t necessary. (I can’t imagine how hard it must be for people 6’6” and above to find standing desks that work for them.)

I walked for about 1.5 hours (with breaks) on the treadmill desks during the first few days. While walking, I noticed a couple of things: I preferred to have some cold water to drink. I also preferred to have a small fan blowing on me.

As for speed, I increased it to 0.9 mph on the third day, but I realized that I needed more practice before I could reach 1 mph. However, this slow speed didn’t bother me; whether burning 100 calories an hour or 80 or 150, any of these was superior to calories burned sitting. The small, regular movement also kept my muscles in action, and activated.

Frequent changes in posture and position

Walking 1.5 hours on a treadmill doesn’t seem like much time, given an 8-hour workday. Which is expected. I never anticipated walking for 8 hours. The treadmill is supposed to be one of many various positions to adopt. Both Levine and Vernikos recommend frequent changes in posture throughout the day (the changes activate the stabilizer muscles). Standing stationary for 8 hours doesn’t accomplish this, nor would the same walking gait all day do it. In fact, long-term standing can result in its own physical issues.

The key is to make your physical movements and activities varied; the treadmill is only one type of movement among many. Standing is another type of movement. Sitting on a yoga ball another. Standing on a balance board is another, and so on. Each change in movement introduces a postural change that activates muscle movement, stabilization, and contraction.

Vernikos explains:

Thus, the shorter but more frequent changes in posture, the greater the benefit to the regulation of blood pressure.

Standing up often is what matters, not how long you remain standing. Every time you stand up, the body initiates a shift in fluids, volume, and hormones, and causes muscle contractions to occur; and almost every nerve in the body is stimulated. If you stand up 16 times a day for two minutes, the body would read that as 16 stimuli, whereas if you stood once and remained standing for 32 minutes, it would see that as one stimulus. … As muscles contract, they pull bone in every which way, even at the low speeds we used, as long as the subjects are upright or changing posture frequently. (33)

In other words, shifting the position regularly is the key, not maintaining the same activity (such as walking) throughout the day. I set a timer on my computer (using the BreakTime app) to cycle a notification every 20 minutes. At this 20-minute mark, I would then change position to some other posture. It’s a different kind of movement and exercise. Vernikos explains:

It can be difficult to convey to people that I am not talking about getting more exercise—I’m talking about a different kind of exertion. I am referring to the multitude of small, low-intensity movements we make throughout the day as we go about the business of living—movements that are related to using gravity. These are the movements that occur naturally throughout the day when you’re doing activities other than sitting. And yet these simple movements—these G[ravity]-habits—are the key to health!” (34)

The authors continually reiterate that you don’t fix the problem by going to the gym more. If you run for 30 minutes on a treadmill, the benefits are marginal. Levine explains that a good cardiovascular workout in the gym might burn 200 calories or so, leaving you exhausted and feeling like you’ve accomplished your needed exercise for the day. But this isn’t the case. What’s more important is what you do for the entire day, whether the main activity is sitting or whether it involves movement.

Levine calls these non-exercise movements all day “non-exercise activity thermogenesis,” or NEAT:

NEAT is the energy expenditure of all physical activities other than volitional sporting-like exercise. It includes all those activities that render us vibrant, unique and independent beings, such as dancing, going to work or school, shoveling snow, playing the guitar, swimming or taking a walk. NEAT is expended every day and in every way and can most easily be classified as work NEAT and leisure NEAT. (25)

Levine says that in one study he conducted (as part of Mayo’s Metabolism Research Unit), their research team overfed the study’s participants by exactly 1,000 calories a day for 10 weeks. Some of the overfed participants gained weight, while others didn’t. Why didn’t some participants gain weight? Those who didn’t gain weight burned off the extra calories by introducing more NEAT activity. In contrast, those who gained weight tended to sit more, not up-leveling their degree of NEAT to offset the extra incoming calories (31). Levine explains:

What we discovered was astonishing. People with obesity who lived in the same environment as people who are lean, sit more—a lot more. Sitting caused the low-NEAT calorie burn of obesity. It was not food that explained the differences between lean and obese people, because we controlled the types of food and the diets were balanced …. People with obesity sat 2 hours and 15 minutes more a day than lean volunteers. Obesity, we discovered, was the archetypal sitting disease. People who are chair sentenced the most are the most likely to have obesity. After a decade of research, we had proved that obesity was a chair addiction. The chair is fattening. (35)

In other words, Levine says that sitting was more correlated with those who had low-NEAT calorie burn and gained weight. He recommends that people offset their sitting by at least 2 hours and 15 minutes a day to counteract the effects of a sedentary job.

As one would expect, the most telling predictor of one’s NEAT level is their job, Levine says. If you’re chained to your computer, your NEAT level will likely be low:

Overall, your job is the major predictor of NEAT. Active work can expend 2,000 calories per day more than a sedentary job. If your job is completely chair-bound, as it is for most Americans, you burn 300 NEAT calories per workday. If your job is upright, such as a homemaker or shop assistant, you can burn 1,300 NEAT calories/workday. If your job is physically strenuous, you can expend 2,300 NEAT calories/workday. (25)

I’m not one of those people who become more active if they eat more. Instead, I’m more inclined to sit and lay down more, letting my stomach—full from overeating—digest and recover. This presents more challenges to a career in front of a computer screen. If we just sit down all day, we become like astronauts floating in space, becoming old before our time, developing chicken legs and probably all the problems that accompany obesity.

Hence the treadmill desk. I initially planned to shift between walking on a treadmill and sitting every 20 minutes, but given that the treadmill desks were on other floors or buildings, this created more disruption to my work. So I mostly walked for about 1.5 hours with a couple of short breaks sitting at a breakroom table in between, and then returned to my regular desk. I thought about buying my own treadmill under my dedicated desk at work, but I worried that the noise of the treadmill—equivalent to a soft white-noise machine—would be disruptive to the engineers around me. I walked all around campus and could not find any other worker with a personal treadmill under their desk.

I consulted with my wife about getting a treadmill for my home office, but she said I must use the one at work more frequently before committing to one at home. She said I’m susceptible to throwing myself headlong into far-fetched ideas and then burning out quickly. The at-home treadmill would need to wait a bit.

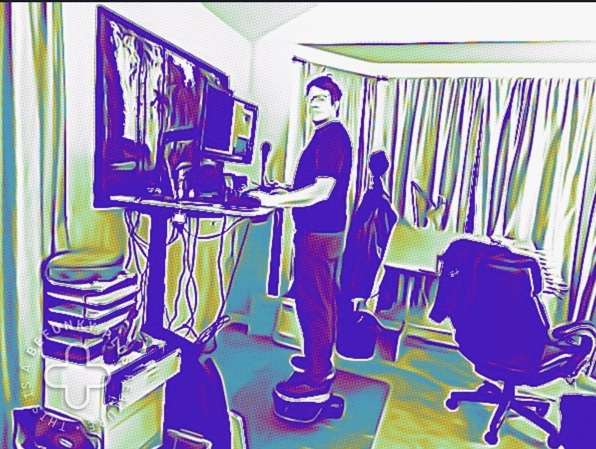

Balance boards

The treadmill desk was cool, but not as fun, I learned, as standing on a balance board while at a desk. There are various types of balance boards. The one I use is a skateboard-like piece of wood on top of a detached cylindrical roller underneath: Revbalance 101 v2 - Balance Board. I initially spent about $150 on a balance board and then later discovered that a long, rectangular piece of wood (literally a shelf) and a thick 4-inch-diameter PVC plumbing pipe would probably do an equivalent job.

(There are a dozen other varieties of balance boards, some one-piece setups, wobble boards, and more. The kind with the detached cylindrical roller on bottom are the most fun to stand on because they allow more varied, back-and-forth rocking motion, but there are also more stable, low-profile options.)

Interestingly enough, Levine doesn’t mention balance boards in his book. He focuses mostly on treadmills. But I found that I love rocking back and forth on a balance board. With my hands resting on the desk or keyboard, it provides much of the needed stability so that I’m not exerting all my attention and effort to balance. I find it really soothing to gently roll back and forth. Occasionally, I’ll remove my hands from the keyboard, such as when I’m watching a video or reading a book, and balance without stabilizing with my hand, but mostly I don’t.

The roller behaves differently depending on the floor surface. If you’re on a plastic office mat, it rolls back and forth smoothly. I have already cracked my plastic mat in multiple places, though. There’s also the occasional squeakiness of plastic on plastic. If you place a piece of smooth wood on the floor, the roller moves more smoothly and quickly, making balance more difficult. But the smooth wood surface is also quieter and more pleasing to rock back and forth.

During the first few days on a balance board, I could feel my glutes and core engage more. They didn’t feel worked over, but they were a little sore. This soreness disappeared the more I used the balance board.

Similar to the treadmill, the balance board elevates your height by 8 inches or more. This creates a similar issue that I solved with the paper-ream hack on the treadmill earlier. My standing desk at home rises to the height I need. Additionally, my monitor is on a swing arm that easily adjusts higher too. But not my desk at work. Just like with the short treadmill desk, my arms dangled to a keyboard on a desk below (too far to be ergonomic). I prefer to rest my wrists on the desk as I type. To fix the height gap, I got a desk riser that is basically a stand for your monitor, keyboard, and mouse that has a spring lift to go up and down. This allowed me to adjust the computer and keyboard to the correct height.

Overall, the balance board makes standing somewhat tolerable, and it’s a lot quieter than a treadmill. Because the balance board doesn’t make noise, it’s less disruptive to incorporate into my desk at work, which is right next to other engineers in an open-office way. However, any active movement is going to be a visual distraction to those around you, sadly. As a result, I tend to move less on my balance board at work than at home simply because I don’t want to draw attention to myself.

Because of the reduced movement, after 20 minutes or so, my feet started going a bit numb. At home, I move a lot more, including “jump-sliding” around to move the roller and sometimes sliding off the board. (By jump-sliding, I mean trying to move the position of the board and roller while still standing on it.)

A lot of colleagues at work don’t realize I’m standing on a balance board. For example, a colleague who sits diagonal to me didn’t notice until someone else came over to ask me about it. However, the other day I was jump-sliding to try to move the roller back into a centered position, and my neighboring colleague (to my left started) to get nervous and said he was worried that I might fall on him. Given his reaction, I either need to move to a more isolated part of the office or get a less rocky balance board. I’m thinking that perhaps with a longer board and a smaller roller, it will appear less dangerous to my colleague. Or I might simply need to get a balance board without a roller, like the Plane from Fluidstance.

Yoga ball

I initially started switching between sitting in my chair and standing on the balance board, but before long, I ditched my chair in favor of a yoga ball (at least a thome). I’d had the yoga ball for a couple of years, purchased during some previous therapy effort to strengthen my lower back. But at the time, I couldn’t entirely adopt the yoga ball full-time, so I abandoned it. Now I found a new use for it. The yoga ball (mine is wrapped in a leather covering) provides a nice alternative to standing. The yoga ball allows me to move my hips around a bit more, and sometimes, when I’m feeling playful, even bounce up and down a bit.

Sitting on the yoga ball differs from sitting in a chair because it allows more hip and pelvic movement and forces me to straighten my lower back more (rather than relying on the back of a chair), but it also isn’t comfortable long-term. After 20 minutes of sitting on the yoga ball, I’m ready to switch to standing. And vice versa.

The yoga ball also offers a variety of uses and positions. Instead of sitting on it, I sometimes kneel on it. (This posture simulates some backless chairs that involve kneeling.) Kneeling on the ball, with my back straight, requires a bit of balance and effort (more than sitting).

However, I am mixed about the yoga ball. From studies I’ve glanced through online, most people slouch on a yoga ball and end up with more “spinal compression” than benefits. This happens partly when you tuck your feet into the ball to keep it from rolling. The yoga ball might not work for me long-term.

Also, the yoga ball that the facilities group provided to me at work is more similar to the yoga balls in the gym (no leather covering, no handle to move it around), and it wasn’t inflated as high. I’m still learning how to properly sit on a yoga ball.

The anti-fatigue mat

Finally, I invested in a textured anti-fatigue mat for those times when I simply prefer to stand. The mat I purchased has some ridges and other shapes, in addition to some cylindrical rollers that my feet can roll back and forth. The standing mat makes standing a lot more tolerable, especially because our feet have so many nerve endings. It’s a welcome respite (especially after standing on a balance board for a long time) to activate those nerves on my feet. Even so, I find that standing in a single place, flat on the floor, gets boring quickly.

Constant rotation

As I mentioned, I switch positions every 20 minutes: from balance board to yoga ball, from yoga ball to standing, from standing back to balance board, then to treadmill. All these objects mean my desk area resembles a little gym area, but that’s the only way for me to make standing fun. Introducing variety helps make standing more engaging and interesting.

As an added bonus, I have some simple physical therapy (PT) exercises that I also work in during moments of rotation. These PT exercises are aimed at strengthening my right calf that I keep straining when I do forceful jumping during basketball. The PT exercises consist of side planks, eccentric calf lowering, crab walks with a Theraband, and lumbar spine extensions. (There’s an unused meditation room at my work for these activities.) When I switch positions, I’ll do a quick two-minute PT exercise. This also keeps the blood flowing.

Overall, it sounds like a lot of movement, which would interfere with focus and make me less productive. And most likely I will adjust to longer intervals (meetings also break this up). But the larger idea is that frequent physical movement will make me more awake, alive, happy, and focused. Plus, oftentimes disruptions will kill this momentum. I’m still early on in this experiment and plan to provide updates throughout the year.

Challenging culture and expectations

This is my first couple of weeks experimenting with life with reduced chair use. There are some inescapable situations where sitting is likely mandatory—driving, eating dinner with family or colleagues, attending meetings, and so on. But if I can stand and move as much as I sit, I think I’ll have won an important battle against the sedentary lifestyle of a career in tech.

One challenge will be to change culture and expectations. In places where sitting is expected, what if I choose to stand? Instead of an office chair, a yoga ball? Instead of sitting while eating, walking while eating? And so on. I attended a high school basketball game the other night with my kids and wanted to stand. The only way to do this without calling attention to myself was to move to a corner at the top of the stands. I imagine this awkwardness will be a sign of more scenarios to come. This should be a good series of posts that I will continue adding to throughout the year.

Links to products

I mentioned a few different products in this post. The following are links to the products on Amazon. (I don’t receive affiliate commissions for any of the links or products.) I can vouch for any of these products—they are excellent:

- Vivora Luno Exercise Ball Chair

- Revbalance 101 v2 - Balance Board Sports Trainer

- Bamboo book stand

- FEZIBO Standing Desk Anti Fatigue Mat

- Jarvis Bamboo Standing Desk

- BreakTime timer app

- X-Elite Pro XL Standing Desk Converter

- HUANUO Single Monitor Mount

References

Levine, James A. Get up!: Why your chair is killing you and what you can do about it. Macmillan, 2014.

Vernikos, Joan. Sitting Kills, Moving Heals: How Everyday Movement Will Prevent Pain, Illness, and Early Death–and Exercise Alone Won’t. Linden Publishing, 2011.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.