My conflicted thoughts about the decentralized web (while taking the Census of Technical Communicators survey)

- About the Census Survey

- Advertising’s impact on the web’s original ideals

- A web without advertising is naive

- How other content is invisible

- Conclusion

Listen here:

About the Census Survey

Researchers at Concordia University (including Saul Carliner) are conducting a “Census of Technical Communicators.” The survey takes a while to complete (20 min.), but it’s well worth the time, and I’m fascinated to see the upcoming results. You can take the survey here: Census of Technical Communicators Survey.

Some of the census questions will prompt some serious reflection. For example, these two questions:

- As a technical writer, where do you feel the most pain or friction?

- How do technical writers in your organization feel the most pain or friction?

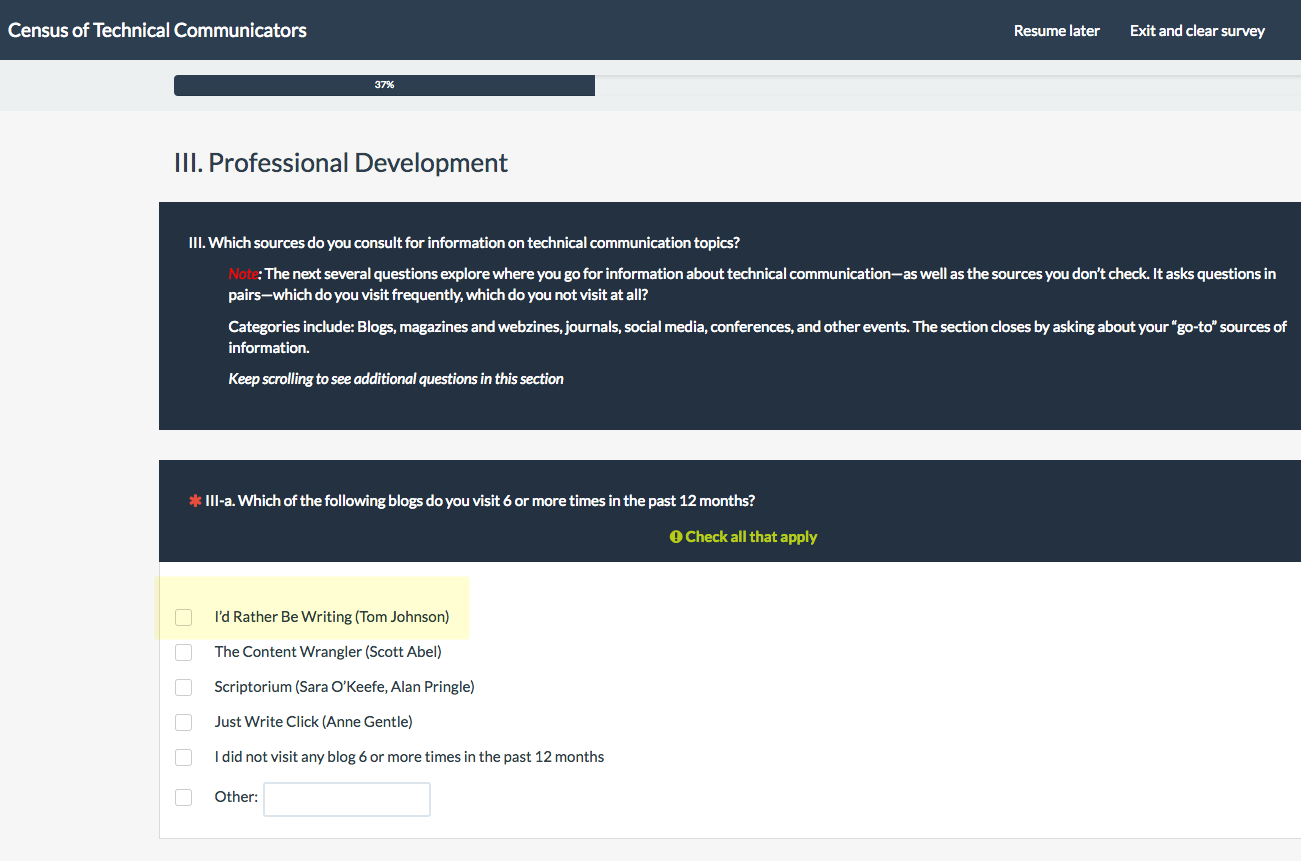

There’s also an entire section about resources you consult for professional development, including blogs. The survey names several blogs specifically, including the one you’re reading:

Advertising’s impact on the web’s original ideals

I’m excited to see blogs listed as sources for professional development here, because in my view it celebrates the decentralization of the web. The very fact that I would be listed among other sources such as peer-reviewed journals, formal conferences, or other trade magazines for professional development suggests that the dynamics of the web have destabilized the hierarchy of information in interesting ways.

Given that a Decentralized Web Summit just ended (I didn’t attend but there are recordings), it’s worth making a few extra notes on decentralization. In a post summarizing highlights from the conference, Computing summarizes takeaways from two key speakers (the speakers were Mitchell Baker from the Mozilla Foundation and Brewster Kahle from the Internet Archive). Computing explains:

The ideology of the web’s early pioneers, according to Baker, was free software and open source. “Money was considered evil,” she said. So when companies came in to commercialize the internet, the original architects were unprepared. “Advertising is the internet’s original sin,” Kahle told the packed room. “Advertising is winner-take-all, and that’s how we’ve ended up with centralization and monopolies.”

At the conference, attendees presented utopian visions of how the future of the internet could look. Civil, a new media startup, proposed crowd-supported journalism using cryptocurrency micro-payments. Mastodon, a decentralized and encrypted social network, was commonly referenced as an alternative to Twitter. As Facebook and Google continue to monopolize the digital advertising ecosystem – recent estimates say that the two companies control over 70% of digital advertising spending globally – the promise of a decentralized web, free from the shackles of advertiser demands is fun to imagine. (Can We Decentralize the Web?)

In other words, the web was founded on free software and open source, but advertising ruined the purity of these ideals.

While web enthusiasts have traditionally celebrated decentralization, the recent political scene has caused many to question the value of decentralization. Given that external entities (e.g., Russia) can destabilize our sense of real news by injecting fake, polarizing news stories circulated through social media channels (e.g., Facebook), many have called out the downsides of a decentralized web. In a centralized web, presumably these fake stories would be filtered out by judicious editors.

So given this context, I can only wonder whether there are downsides with my blog appearing in this list of professional development resources. Maybe the editors of TC peer-reviewed journals look at my site and shake their heads, thinking there goes that crazy blogger again, cranking out more new posts that have people spinning around like wild chickens.

While I would never intentionally post fake news on my blog, there are some undeniable characteristics inherent in blogging that are questionable. For starters, you have to crank out a lot of content on a regular basis. For example, see this post from a professional blogger explaining how she makes a living blogging. She writes 58 posts per month for various sites in order to earn $5,100/month. That is about 2 posts per day. This rapid production of content feeds the social media machine, creating little “bursts of attention” that entice readers to visit a site. Each page visit contributes to eyeballs on advertising media, which generates revenue for web businesses.

This is why at the Decentralized Web Summit, the speaker would say that “Advertising is the internet’s original sin.” It’s not just that there are ads on sites; the problem is that many sites naturally gravitate toward activities that maximize or optimize views on the page, primarily because of advertising. While sure, long content (~1,500 to 2,000 words) has readership, and Google’s search results try to favor long, information-rich content, short little posts often do the trick much more efficiently. Especially if you create clickbait titles, with short posts you can entice people (who are standing in line at a grocery store, taking a two-minute break at work, or hiding out in the bathroom) to visit your site and read a short little article for a tiny hit of information. The lightweight post will fulfill its purpose of bringing more visits to your site.

From an author’s point of view, you can spend a week writing a one 5,000-word article and get maybe 500 views, or a spend a week writing five 500-word articles and probably get 3x as many views. Which activity better optimizes for page views? Shorter, lighter-weight content simply performs better. (By “short” I mean anything that would still qualify as a blog post rather than a longer journal article or chapter.) The barrage of this short, superficial content ultimately distracts readers from immersion in more information-rich, substantial learning sources.

So while on the one hand I might celebrate seeing my name in this Census of Technical Communicators survey, it might also be a sign of our intellectual decline. Sorry ‘bout that.

Actually, although most know me primarily as a blogger, I don’t consider myself in the same category as “professional bloggers.” I only blog as a side hobby outside of my day job as a technical writer. I do have advertising on my site, but it’s not strictly based on the number of page views and it doesn’t keep me financially afloat. I also don’t necessarily make my posts SEO-rich, targeting popular phrases or keywords, nor is my goal rapid-fire content generation. I write about issues that matter to me, and I let readers align if they find the topic relevant.

A web without advertising is naive

In some ways, romanticizing an advertising-free web is somewhat naive. To think that we would get an endless body of rich information on the web (millions of highly accurate, engaging pages; thousands of free, open-source services and other tools) for free suggests that there are content creators and developers just itching to contribute information in non-stop ways with no thought of return. If we didn’t have advertising, both (a) the web would be a lot smaller, and (b) content creators and developers would likely charge subscription fees for their content or services.

Sites like Medium have shown successful models with subscription fees, but the reality is that if you want your content to be discoverable, it needs to be indexed by Google (since this is where 2/3 of traffic originates) and also be free to access. The price of free access and content is advertising.

Eric Holscher, who I consider a champion enthusiast of the open-source movement, had to introduce ads to support the Read the Docs business model. (I think he cringes every time a sponsor gets highly visible slide space or speaker time at a Write the Docs conference.) His compromise is to make sure the ads are ethical. In Ethical Ads, he explains:

Read the Docs is a large, free web service. There is one proven business model to support this kind of site: Advertising. We are building the advertising model we want to exist, and we’re calling it Ethical Ads.

Ethical Ads respect users while providing value to advertisers. We don’t track you, sell your data, or anything else. We simply show ads to users, based on the content of the pages you look at. We also give 10% of our ad space to community projects, as our way of saying thanks to the open source community.

Without advertising, we probably wouldn’t have Read the Docs (in its current form), because no one can sustain this kind of service for thousands of projects for free. For that matter, without advertising, TV would probably not exist in the same form either.

So advertising is the necessary evil required to power free information and services on the web. But what price are we paying for this advertising? How is advertising corrupting us (like the original sin it is)?

Advertising creates a distortion in the very forms of information that we consume — information has been hollowed out, clickbaited, and generated at such a rapid and constant rate that it has warped our attention span and caused us to constantly seek out what’s new. Our ability for deep immersion and flow has been crippled. Advertising hurts our creativity and intellectual engagement.

I know that to some extent, I am contributing to this degeneration of information. Even with my lengthy, longwinded posts, where I try to question assumptions and think critically, I also fall prey to more lightweight, unchecked content. I’m under (self-imagined) pressure to produce more content, to keep the page views high on my blog, to stay a relevant hub for information. I have to produce, produce, produce for my site to stay visible and relevant.

Even beyond the incentives of advertising, there’s a high that comes from social interactions. The interactive nature of blogging — seeing my posts get retweeted, favorited, commented, discussed — makes me think the content matters, that it is making some contribution. Even now, I can feel that I’m diving into a contentious topic, that I will surely hit a nerve with some groups and spark debate. I can already see the discussions coming. And this feedback, even before it materializes, feeds the drive to blog even more. In this way, advertising encourages this model of short-form, lightweight content, since it increases the number and frequency of these interaction highs.

How other content is invisible

The forms of content that the medium of the web optimizes for is a topic that I have been thinking about regularly with my Academic/Practitioners Conversation project. Deep down, I think academics and the traditional publishing world, where journals and trade magazines close access to their content behind paywalls, where content is distributed via PDF, where review and publishing processes take between 6-12 months, and where researchers must wait months before even getting university approval to conduct research — will simply not survive in the current web. Very few will discover, read, or share the content — at least, not enough to turn revenue through the advertising machine (or even to achieve goals of online presence). As such, the content will become irrelevant and invisible except to those inside academic walls (who are not at the mercy of paywalls, and who know how to navigate the backroads of these academic systems to find relevant content).

It’s unfortunate that academics — who produce more information-rich, in-depth content — are trapped in a “web-invisible” system by the structures of their institution. Their career stability rests on achieving tenure, and tenure is granted only to those academics who publish feverishly in this web-invisible space — in the peer-reviewed journals, thick with the discourse that, as Rebekkah Anderson pointed out in a recent presentation at SIGDOC, practitioners brace for pain before reading (if they find the content at all).

This might be fine since the audience, as some have pointed out, consists mostly of other academics who understand and have access to this system. However, TC academic programs must sell professional TC preparation for prospective students, and to do that, they must be visible to prospective students. And how can they establish credibility and engagement to these prospective students if they produce invisible, inaccessible content?

The only way out of this isolating discourse into the visibility of the web is for academics to become bloggers. But they will not become bloggers because the very methodology upon which their academic souls are forged requires them to be rigorous and methodical, challenging assumptions and avoiding claims that haven’t been carefully researched, analyzed, and backed by peer-reviewed publications. Few will ever crank out multiple posts a week, or even per month. And if they do blog, they’ll rarely pour their energies into blogging because blogs aren’t tied to tenure, and so they are only a distraction to their real work, not a space where they truly engage. Even so, a quick sketchpad that accompanies their real research and passions could have the inklings of some visibility.

Conclusion

Coming back to the Census survey — definitely take the survey. When you arrive at the part of the survey that asks you to identify sources you read, think about some of the ideas I’ve tossed around here. Certainly, this Census survey doesn’t slant you to think any source is better than another. In fact, this survey is likely a model for how surveys should be properly constructed and carried out — soliciting fair, unbiased responses. I am only commenting on my own ideas swimming in my head after I finished the survey, and how I come to terms with seeing my name and blog as a source for professional development.

I don’t know if I have corrupted good reading habits. Surely for some, I’ve sparked ideas that maybe weren’t there before. For others, I might have only distracted you from immersion in better sources. For better or worse, I will keep blogging because it is the inevitable route to follow on the web.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.