Single Sourcing and Redundancy

Although we have a lot of single sourcing tools, and the term single sourcing is used constantly in tech comm conversations, I've never had a firm answer to the following question: How should the print output differ from the online output?

Let's assume that you have all your content in a help authoring tool. You have two outputs configured: an online help and a PDF manual. Should the two formats contain about the same content?

This question isn't as relevant with some platforms, such as wiki-based platforms. With MindTouch, for example, users can choose to create their own table of contents and render it into a PDF on the fly. Other browser-based platforms, like Mediawiki, may keep all of the content in online formats only.

However, if you're using a help authoring tool, such as Flare, Robohelp, Author-it, Doc-to-Help, or some other tool (such as DITA Open Toolkit), you're often presented with a variety outputs to choose from. Generally you store your help content in the help authoring tool and publish selectively and strategically to the outputs you want. But the strategy about what should you publish to each output tends to be something that gets overlooked.

You can publish to both outputs with varying degrees of redundancy. I'll explore four basic options.

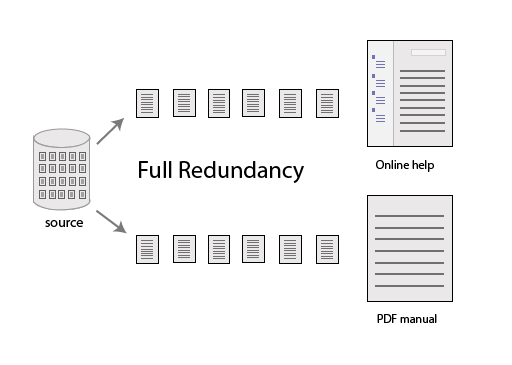

Option 1: Full Redundancy

One option is to keep the online help and printed guide pretty much the same. Sure, the PDF has a title page, table of contents, and maybe an index. But there's not a whole lot of difference between the printed guide and the online help. The content is redundant between the two mediums. Users choose the medium they prefer.

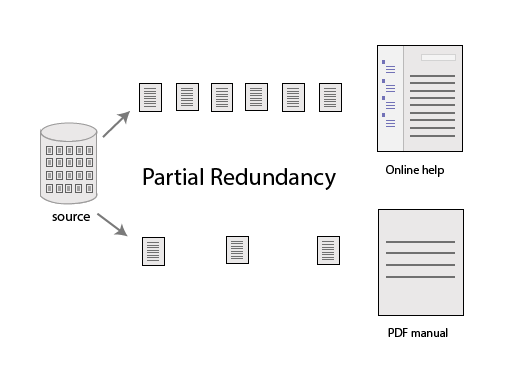

Option 2: Partial Redundancy

Another option is to publish a subset of the topics to one output, usually the PDF manual. Your online help might be a giant repository of all kinds of content, as you write for the long tail. But the PDF manual would only be a fraction of the total information. The printed guide just contains the mainstream tasks and concepts.

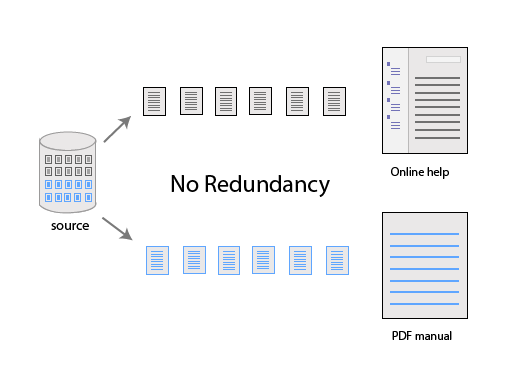

Option 3: No Redundancy

A third option is to make the PDF manual substantially different from the online help. Proponents of this camp believe the scenarios for which people access the online help versus the PDF vary significantly. Because of the different scenarios, the formats warrant entirely different content.

For example, I've heard people say, "If it's in the online help, why would users want to view the same content in a PDF? Wouldn't users want to see the information presented in a different way? Otherwise, if the content is the same, what's the point of having a different format?"

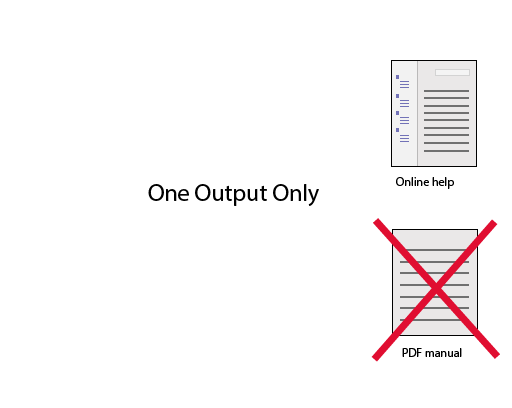

Option 4: No PDF

A fourth option might be to dispense with the PDF altogether. When you have help online, do you really need a printed guide? Printed guides get quickly out of date as software changes, especially in agile environments. When users download and print long manuals, and then bind and shelve them for reference, these outdated manuals become a liability. If you have a web-based platform where you're authoring and publishing content, you might just stick with one source.

My Analysis

Let's break down the question by analyzing in depth why people would access both formats. In general, advanced users (users already familiar with the application) don't print guides. If you already know the application, there's little reason to print off the full manual or even read the help. Instead, advanced users usually search the help for answers to specific, often difficult questions.

The printed guide mainly serves the new user. You don't want to bury the new user with a ton of information, so you probably would select Option 2: Partial Redundancy. The printed guide could be enough to introduce new users to basic concepts and tasks to get them started. You can add references to the online help for more advanced information.

With this strategy, the emphasis of the printed guide would be more of an introductory guide, with the assumption that users have limits to the amount of new information they can process. Sure, users can print a 700-page guide and plan to read 50 pages a day for the next two weeks, but most likely the user who prints a 700-page manual will die of a heart attack as he or she watches the printer print page after page for two hours straight.

Writing for the Long Tail

Earlier I used the phrase "writing for the long tail," but I didn't explain what I meant. By long tail, I'm referring to the non-mainstream help topics. Usually technical writers aim to cover topics of interest by the majority, the 80% rather than the 20%. Usually people assume that the 20%, the non-mainstream topics, aren't worth including since they're used by so few.

However, Amazon.com found that doing well in the long tail game proved more successful than sticking with mainstream products. The aggregate sales of the non-mainstream products adds up to sales greater than the mainstream products. In other words, you may only sell one Grateful Dead coffee mug, one Nicki Minaj wig, one lizard-skin wallet, one Jerry Mumphery rookie card (who's he?), and one used hubcap, but when you keep adding up these odd sales, they begin to outperform the Disney DVDs and other mainstream product sales.

With help content, if you write for the long tail, you choose to include the non-mainstream topics that might not otherwise fit into a guide. Think of all the knowledge base articles that get written by support center agents — the advanced technical notes, the information about bugs and workarounds, specific scenarios for ad hoc roles, situations specific to particular languages or regions, and so on. Each topic may get only 25 hits instead of 2,500, but when 1,000 people each click the topics, their aggregate traffic exceeds the mainstream.

Usually the long content doesn't fit well into help material. But where should it live? About the only place for long tail content to thrive is online. If you include all the miscellaneous information into a PDF manual, users will scratch their heads about why you included so much seemingly random, category-resistant content. It doesn't fit the book-reading paradigm that values sequence and order.

As a best practice, I think it's good to include the long tail content online, either with the online help or on a connected site, and let the user search to find and retrieve the topics. But don't single source all this long-tail content to the PDF manual. Let the PDF manual stick with the basics, targeting the new user who is learning the application. Keep the PDF readable in an attractive way.

I'm curious to hear what your practices are with redundancy between online and print outputs. Which option (if any) do you follow?

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.