Notes for Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint for Urban Vitality

Listen here:

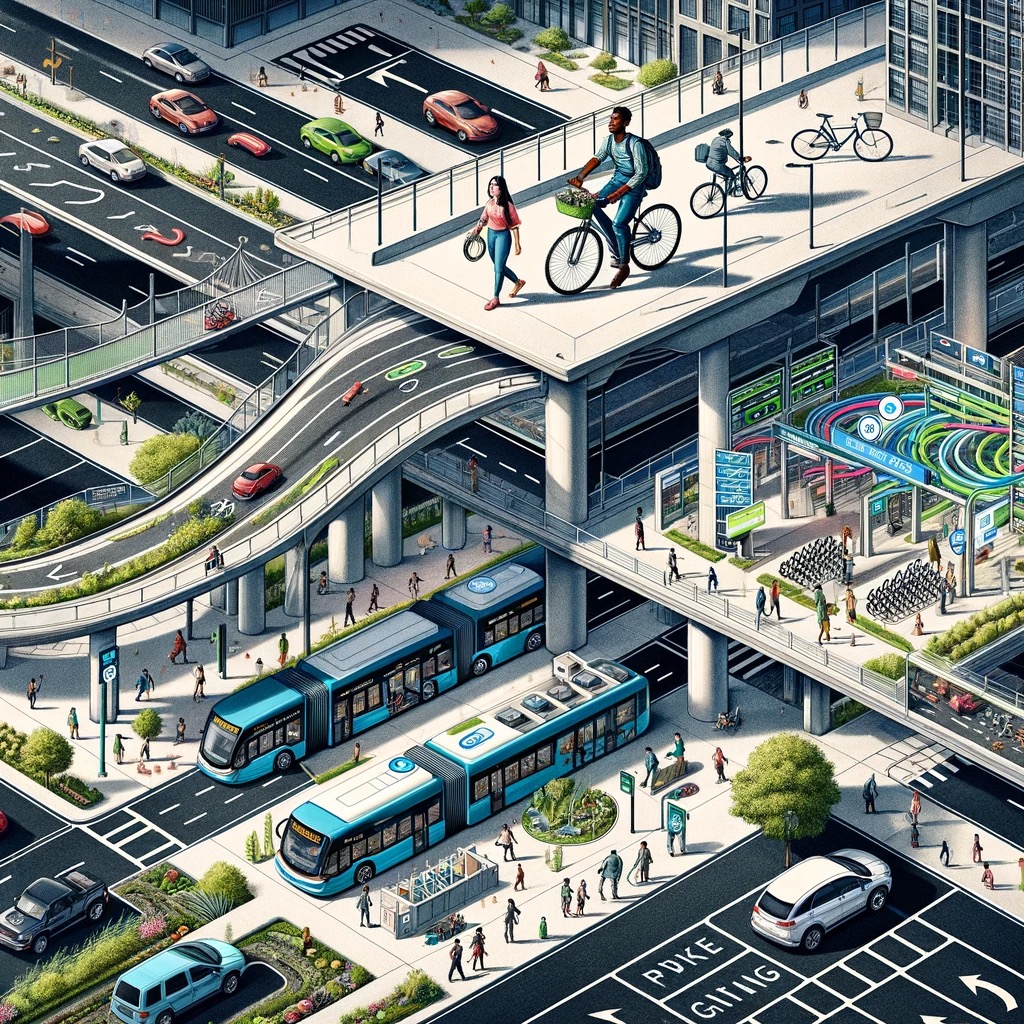

In the following sections, I’ve pulled out my 12 more concrete takeaways from their book. The authors aren’t this explicit in identifying 12 techniques, much less numbering them. This is just my desire for more concrete strategies and takeaways. I created these notes for a book club discussion focused on automotive and transportation books. Note that these notes were AI-assisted, and images were generated by DALLE3.

- 1. Embrace e-bikes to replace more car trips and attract new demographics to cycling

- 2. Integrate bicycling and public transit to enable convenient multimodal journeys

- 3. Design infrastructure around complete trips, not isolated modes

- 4. Use social media for activism, storytelling, and political influence to drive cycling adoption

- 5. Incorporate cargo bikes for efficient urban freight and delivery

- 6. Prototype cycling infrastructure with temporary materials to demonstrate benefits, and iterate

- 7. Customize cycling plans based on a city’s unique context and constraints

- 8. Change is hard-fought and requires advocacy through grassroots campaigns and political engagement

- 9. Collect data on usage, safety, and business impact to make the case for cycling infrastructure

- 10. Recognize that urban vitality requires diversifying transportation outside of cars

- 11. Use signature architecture and art to proclaim a vision for a cycling city — inspire people

- 12. Emphasize practical bike designs optimized for urban mobility over recreation or sport

- End result: cycling becomes remarkably unremarkable

- Podcast notes

1. Embrace e-bikes to replace more car trips and attract new demographics to cycling

e-bikes are allowing more practical replacement of car trips with cycling, especially over longer distances.

- E-bikes are often adopted as replacements for cars (not replacement for pedal bikes).

- e-bikes expand access to cycling by reducing physical barriers. They make longer trips of 5-10 km more feasible for people.

- E-bike attract new demographics to cycling.

- In the Netherlands, e-bikes make up a huge percentage of new bicycle sales. A more current statistic indicates e-bikes comprise 57% of new bikes sold (Pedaling into the Future).

- People can travel further distances on e-bikes, expanding the catchment area (area from which people use a service) and geographic coverage of cycling as transport.

- Cargo e-bikes enable practical transport of children and goods by cycle.

2. Integrate bicycling and public transit to enable convenient multimodal journeys

Bicycles and trains have a complementary and synergistic relationship:

- Bicycles provide an efficient solution to the “first and last mile problem” for train commuters. People can bike to the station at their origin, and bike from the station to their destination.

- Having ample bicycle parking at train stations enables this first/last mile connectivity. The Dutch invest heavily in parking facilities.

- Not all trains allow bikes on board. For example, during rush hour, bikes aren’t allowed on Dutch national trains (see source). So the majority of people park their bikes at the station.

- OV-fiets, the national bike share system located at train stations, further solves the last mile problem for visitors. For as little as $5.50 per day, people can rent a bike on the spot.

- Surveys show over 90% of OV-fiets users say it improves train connectivity. The OV-fiet system has more than 22,000 bikes across 300 locations.

- At major stations like Utrecht, up to 70% of travelers arrive by bicycle. It’s extremely common to bike-train commute.

- The bike extends the feasible commute distance for train travelers, expanding labor catchment areas.

- Biking and public transit together form an inexpensive, efficient, healthy, and environmentally-friendly mobility system.

3. Design infrastructure around complete trips, not isolated modes

When designing transportation networks, it’s important to look at the entire journey experience rather than just optimizing isolated parts.

- Transportation is inherently multimodal — few trips can be completed with just one mode. So the connections and transitions between modes are critical.

- People care most about getting safely, quickly, and comfortably from origin to destination. The separate legs are just components of that holistic journey.

- If certain legs are inconvenient, unsafe, or unavailable, the entire journey fails. Missing links break the chain.

- Looking narrowly at any single mode fails to recognize the interconnectedness of transportation networks.

- Journey planning requires collaboration across all responsible agencies — transit, cycling, roadways, land use etc. To be successful, you can’t afford to silo.

4. Use social media for activism, storytelling, and political influence to drive cycling adoption

Technology and social media enable powerful storytelling and advocacy to drive cycling adoption.

- Platforms like Twitter, YouTube, Instagram allow people to share stories/photos/videos of their cycling experiences. This makes cycling more visible and relatable.

- Hashtags like #joyofcycling help build a shared narrative around the benefits of cycling.

- Geo-tagging bike infrastructure shows policymakers where improvements are needed, crowdsourcing bike data.

- Social campaigns can allow mainstream cyclists to reach and influence decision-makers.

5. Incorporate cargo bikes for efficient urban freight and delivery

Cargo bikes are emerging as an efficient delivery solution for packages and freight in cities.

- Large delivery trucks are inefficient in dense urban areas — they cause congestion, lack parking, block bike lanes, and disrupt pedestrian traffic flows.

- Cargo bikes have much more flexibility to navigate narrow streets, bike lanes, and pedestrian zones that trucks cannot access.

- Electric-assist cargo bikes can haul substantial loads, up to 500 lbs or more. They’re sufficient for many intra-city parcel deliveries.

- Cargo bikes significantly reduce delivery costs — some companies estimate a 70% cost savings per stop versus vans, with faster delivery times too.

- Packages are protected from weather inside cargo compartments or boxes. Some have cold storage for food deliveries.

- Limitations are long distances and very heavy loads better suited to trucks. But cargo bikes dominate the last mile.

- Companies like DHL are leading the charge.

6. Prototype cycling infrastructure with temporary materials to demonstrate benefits, and iterate

Prototyping and tactical urbanism* are techniques the Dutch use to build support and adoption for cycling infrastructure:

- Quickly setting up temporary bike lanes or traffic calming features with cones, planters etc. lets people experience the benefits firsthand.

- Starting with pilot projects on low-traffic side streets is often an easier sell than removing car lanes on major roads.

- Pop-up protected bike lanes can demonstrate benefits like safety, traffic flow, business access. This can build public support for more permanent infrastructure.

- Iterative designs with temporary infrastructure — tweaking bike lane width, intersection treatments, pavement markings based on observations and feedback — can help the permanent bike infrastructure be more successful.

- Gradually upgrade temporary materials to more permanent infrastructure as support and funding grows.

- Build datasets about usage and safety to make a case for permanent infrastructure.

*Tactical urbanism: A grassroots approach to neighborhood building and activating public spaces using short-term, low-cost, scalable interventions and policies

7. Customize cycling plans based on a city’s unique context and constraints

Although we can learn principles from the Dutch, each city requires a customized cycling strategy based on its unique context:

- Dutch cities span medieval towns to post-war redevelopment to suburban centers — requiring tailored approaches. There isn’t a “one size fits all.”

- Factors like topography, climate, layout, transportation mix, politics, culture all influence appropriate cycling plans.

- Don’t apply cookie-cutter principles that over-simplify complex transportation ecosystems that differ across cities.

- Some opportunities arise from unique city events/histories — for example, Rotterdam’s postwar rebuilding opened options to rethink the city. But even when places were refashioned for cars, those roads were unchangeable.

8. Change is hard-fought and requires advocacy through grassroots campaigns and political engagement

Cycling transformation in the Netherlands was an uphill battle, not guaranteed. People had to fight for it.

- Cycling wasn’t implemented from the national level across the Netherlands. Instead, decades of advocacy and grassroots activism in each city were required to shift policies and public opinion towards cycling.

- In the post WWII era, cars and roads were seen as symbols of progress. Cities demolished neighborhoods to build roads and highways.

- The turning point came in the 1970s, as traffic deaths mounted, especially of children. Protests erupted demanding safety. Campaigns like “Stop Child Murder” sparked outrage and shifted blame to the system, not just drivers.

- The 1973 oil crisis demonstrated the perils of auto-dependency, spurring questions about car-centric planning.

- Infrastructure was won inch-by-inch, block-by-block. Some city council votes were decided by thin margins.

- Setbacks happened too. After early progress, many cities stalled in the 80s and 90s before reviving efforts.

9. Collect data on usage, safety, and business impact to make the case for cycling infrastructure

Rigorous data collection was key to demonstrating the economic benefits of cycling infrastructure and overcoming business objections.

- Many merchants initially opposed removing parking/lanes for bike paths, fearing loss of customers arriving by car.

- However, studies in some Amsterdam neighborhoods showed cycling infrastructure dramatically increased visitors — that it was good for business. In some places, along with pedestrianization, the change led to 30-40% growth in store revenue on previously car-centric streets.

- Vibrant street life and reduced traffic made commercial districts more desirable destinations. These changes made it a place people wanted to live and visit, which had a positive economic impact on the area.

- This evidence-based advocacy converted many business owners into cycling champions.

- Overall, data can paint cycling as a catalyst rather than an impediment for economic vitality and commerce.

10. Recognize that urban vitality requires diversifying transportation outside of cars

City planners should recognize that a car-centric model limits a city’s potential for further growth and densification.

- Once cities reach a certain size and density, continued growth requires scaling back private car usage and infrastructure.

- Cars consume too much space for movement and parking to sustain dense urban cores, leading to sprawl.

- At some point, cities max out if cars are the only form of transport. Car-centric cities have limited density.

- Congestion and loss of walkable character degrade cities’ economic and cultural vitality. For example, the 20-lane highway being built in Austin is a step backwards for their “keep Austin weird” character.

- Urbanity thrives on proximity and human-scaled infrastructure, which at some point cars undermine.

- Public and active transport allow sustainable densities 5-10 times higher than car-based models.

- The most vibrant, thriving cities have diverse mobility ecosystems with far fewer cars.

11. Use signature architecture and art to proclaim a vision for a cycling city — inspire people

The Dutch used *signature architecture and public art to amplify the cycling vision.

- High-profile cycling bridges, tunnels, and art installations make a bold statement about the city’s values.

- It signals to residents and visitors that this city is a place where cycling is integral to the culture and urban fabric.

- A landmark bridge over a major barrier like a river or highway demonstrates high-level commitment to cycling connectivity.

- Whimsical art along bike routes — such as Van Gogh’s Starry Night — reinforces cycling as joyful. It’s public art you can bike through.

- Culture and infrastructure are mutually reinforcing — world-class facilities spur more cycling which justifies more investment.

* Signature architecture: Signature architecture refers to distinctive buildings or structures that become icons or landmarks strongly associated with a city.

12. Emphasize practical bike designs optimized for urban mobility over recreation or sport

Dutch cycling culture emphasizes practical, utilitarian bikes rather than high-performance sports bikes. The bikes are for transport, not sport.

- The bikes have upright riding posture for comfort, visibility, and the ability to look around. No need for athletic flexibility.

- Coaster brakes allow braking without hand involvement, keeping your hands free.

- Chain guards, skirt guards, and other shielding prevent grease on clothes. No need for special gear.

- Built-in lighting is powered by pedal generators or batteries. Allows for riding after dark.

- Fenders and enclosed chains allow riding in adverse weather.

- Rear and front racks and baskets allow for cargo capability and carrying goods and kids.

- Step-through frames allow for easy mounting and dismounting.

- Durable aluminum or steel frames can withstand years of urban use with minimal upkeep.

- Accessories like kickstands, mirrors, and bells provide for urban maneuverability.

End result: cycling becomes remarkably unremarkable

The author writes “…it is only when everyone else can choose biking as an entirely normal way to get around that other nations will have succeeded in building their own remarkably unremarkable cycling cities” (214).

What does the phrase “remarkably unremarkable” mean?

- It’s remarkable in the sense that the Dutch have achieved something very impressive — high cycling rates, extensive infrastructure, mainstream cycling culture. This is worthy of remark and attention.

- But it’s also unremarkable in the sense that cycling is so normalized and integrated into Dutch cities, it’s become a regular, everyday way of getting around. It’s not viewed as exceptional or outlier behavior. “Cyclists” aren’t a subset of the population — everyone is a cyclist.

“Unremarkably remarkable” captures this dual nature of cycling in the Netherlands — it’s both noteworthy in its scale and success, yet also mundane and ordinary because it’s been so seamlessly incorporated into the urban landscape.

Podcast notes

In the podcast, I mentioned some iconic art that I really enjoy on my ride. Here’s it is:

I also talked briefly about my multimodal commute, captured in this Commute Seattle spotlight video, embedded here:

Slides are here.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.