10 Ways to Gather Feedback from Users

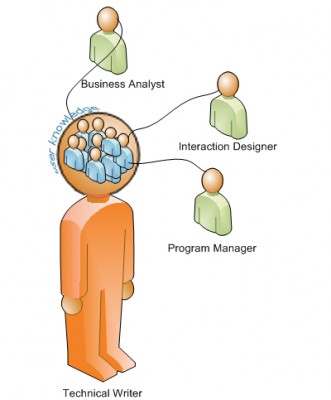

Ever since I came back from Doc Train West and had my epiphany about the transformative, empowering nature of user knowledge with the tech writer role, I've wanted to build stronger connections with my users.

Having extensive knowledge of user behavior can make you a valuable asset on any project team, allowing you to deliver key advice on application design and development. Additionally, as in any writing situation, a detailed sense of audience helps you write content much more useful to the audience.

In short, the more user knowledge you have, the more powerful you are as a technical communicator. Here are 10 ways you can gather feedback from users.

1. Create a "Send Feedback" Link in Your Online Help

I add a Send Feedback link on every page of my online help. This allows users a point of connection when they can't find what they're looking for in the help. I add the Send Feedback link on the master page of my webhelp target, so one instance in the footer automatically propagates to every help topic.

The link contains a javascript that opens the user's default email program and inserts the absolute URL of the help topic he or she was on at the time. This link is important in identifying the problem the user was trying to solve, because often the messages users send are cryptic and ungrammatical. It also lets you know they were actually in the help. Here's the script:

<script type="text/javascript">/*<![CDATA[*/document.write("<a href="mailto:youremail@company.org?subject=ACME%20Application%20("+document.title+")&body="+location.href+"%0A%0A"+"">Send Feedback</a>")/*]]>*/</script>I've heard some people say they have feedback links in their help and never receive any customer responses. For an application used by about 1,500 people, I receive about one feedback email every two weeks. The email is automatically distributed to a list that includes our core project team.

It's cool to receive feedback from users, except when they point out an inaccurate step in the help or a broken link. At that point it's a little embarrassing, but still preferable to blissful ignorance.

Other times they're trying to do something that's not possible in the application. For example, two nights ago I receive an email at 9 p.m. from a user asking how to perform a task. At first it wasn't clear what he was asking, but by visiting the embedded URL, I could piece together his real intentions.

The program manager saw the email and immediately responded, and I chimed in to the conversation as well. The user who asked the question was stunned at the quick response, and I ended up fixing a step in my help.

2. Track Help Usage with Analytics Tools

Most companies have an analytics tool to track visitors to their corporate site. For example, we use Omniture at my work. Others may use Google Analytics or other site metric tools.

You can add a script to each of your pages that tracks the pages most commonly viewed. From these stats, you can see what problems users struggle with most. (If you don't know where to get the script, ask your company's web metrics guru.)

Unfortunately, looking at help site metrics can be a little depressing. I counted about 37 visitors in a month once. Whatever the numbers, viewing help metrics is a reality check.

You can also pull statistics from your application's database or logs (assuming your application has them, and that you can convince a techie to get them for you). This can help you understand actual application usage and trends. Based on the most commonly used functions, you might strengthen those sections in your help. You could also make your help's home page a list of the top 10 topics users search for.

3. Monitor Support Center Call Logs

If you have a support center, the service agents usually log calls in an incident management system, and then document solutions and workarounds in a knowledge base. It's important to stay aware of support center trends. You can often generate reports from their support logs.

You can also view the hits on various topics in your support center's knowledgebase. If possible, try to integrate your own help material with the support center's knowledgebase.

At my organization, the service desk agents have an incident management system that ties in with their knowledgebase. Apparently the integration is so close that keywords from the incident log automatically show relevant search results from the knowledgebase.

The first report I analyzed from the support center showed me that a lot of users had trouble logging in to the application. They also needed help setting up their committees and designating the correct roles. Using this knowledge, in the next release of the application we added additional help links to the login page.

4. Observe Users in Their Environment

It's helpful to observe users in their own environment. For example, the main users for one of our applications are secretaries. I happen to sit near a secretary, and from casual observations, I can tell she spends much of her day scheduling meetings in Outlook and handling other administrative tasks through email.

She's not a break-it-to-understand-it techie by any means, but she's hard working and organized. And she seems to prefer print material. Mostly she seems exasperated most of the day, constantly looking at full Outlook calendars.

Wear your help ethnographer hat and go visit your user's environment. You can often learn a lot about your audience. At a previous company, we provided documentation for financial analysts, whom we never met. One day we went on a field trip to one of their offices. The financial analyst we intended to visit was gone (playing golf with clients, I think), but the secretaries were busy at their desks, buried in paperwork.

We finally did meet some financial analysts at a smaller office. It turns out they had never read the documentation we wrote, as far as they knew. It was somewhat of a shock to both of us. Previously I pictured an aggressive financial analyst skimming the help as he logged numbers in spreadsheets. In reality, we were mostly writing for their assistants.

5. Contact Your Users Periodically

You can contact your users periodically with a friendly email asking if they have any questions or feedback about the application. I don't often do this, but I have been starting to do it more lately.

Try to think of the last time someone from a major product you use (Microsoft, Adobe, TechSmith, etc.) contacted you to see how the product was working for you. Imagine if a person from Adobe just called to see if you needed any help with Photoshop. My jaw would drop to the floor, and I would never forget this non-marketing-based outreach.

An email can provide an important piece of contact information when a user needs help. They may not respond at the time (in fact, they may probably ignore you entirely). But when they're frustrated, they'll remember your email and seek you out. And people who find answers from one source tend to return, like a stray cat to a plate of milk.

Of course, being sought for help may be the last request you want -- another to-do item on your already overburdened plate of assignments. If that's the case, then yeah, you may not want to be reaching out to customers. But if you're trying to fill yourself with user knowledge, the email may pay off.

6. Build User Profiles/Personas

It's becoming more and more common to create user personas as means to ground your understanding of your audience. Personas are composite sketches that describe a typical user and his or her behavior. More specifically, a persona is a stereotypical description of an imagined user of your application, complete with a fake name and photo and all kinds of quirky details. Personally, I've never written a persona sketch, but I do have several in the back of my mind as I write.

You can pin these personas up around your computer or office wall (they might make great conversation starters) to help you remember who you're writing for. Envisioning your audience as specific people ("Jim," or "Susan") can help you write with greater clarity and focus than writing with only a vague crowd of faceless people.

7. Establish Regular Communication Through Biweekly Tips

Almost no user ramps up to the power level on your application the first week he or she gets access. Instead, the user most likely learns just enough to get by; he or she figures out how to accomplish the needed basics. In this moment of initial learning, the user may read a dozen pages of your 200 page how-to guide. But once somewhat comfortable, he or she lays the manual in its coffin and continues on day after day with basic tasks.

A biweekly tips newsletter (housed on a blog, with posts sent in emails to users) can help spoonfeed that user little bits of knowledge in consumable fashion, helping ramp the user up to a power user in a period of time.

People can learn immense amounts of material if the learning is rationed out, chopped up into little segments and distributed every other week or so. Even the overworked secretary can watch a two-minute video tutorial and suddenly understand that cryptic feature that was really hard to explain in the documentation.

When you spoonfeed your readers with tips, you don't only ramp your users up to a more advanced level, you also establish a line of communication between you and the users. You strengthen your role on the project team as the conduit and connection point for all those using the application.

8. Become a User of the Product Yourself

There's no better way to understand your users than actually becoming a user of the same product. If you can start using the product you're documenting, integrating it into your daily workflow, it can provide a tremendous perspective boost.

The main product I document right now is a meeting management and decision-making tool. When I started using it to record and track decisions for our own tech writing department, it opened my eyes about so many features.

For starters, I noticed that the authoring window was small. A button on the web editor toolbar, however, could expand the window to full view. I found the window expansion button extremely useful, but I had overlooked in my help, since I never had occasion to use it.

You notice little details like this when using the product. For example, I didn't realize the need for a notes-only workflow in the application until I had to push all my notes through a formal minute-voting process. The application needed a streamlined way to process information-only announcements. Returning to my help, I'm now adding a workaround to the minutes process.

9. Create a User Council

At the last STC annual conference, I listened to a presentation on user councils by a writer from IBM. In her user council, she gathered about a dozen users and periodically met with them to gather feedback, test ideas, and do other mind-altering experiments (just kidding) over the course of several months for a beta product IBM was designing.

In return for their participation on the user council, each user received either a monetary sum or some other benefit. The main incentive for participation, though, was that each user had a chance to improve the software he or she spent much of their day using.

The technical writer carefully tracked all their suggestions and requests and periodically sent them responses letting them know the outcome of their feedback, whether their suggestions were used or not. This made the users feel that IBM was carefully listening to their suggestions.

If you can gather a user council, it's an excellent idea. Often the user council is spearheaded and run by a program manager. Even if you're not invited to participate in the meetings, you can follow the notes and other feedback compiled from their sessions.

10. Watch a User Try to Perform the Tasks in Your Documentation

Every once in a while, when someone asks if they can help me, I ask if I can watch them do the tasks in my documentation. This works well for interns in your department, or even other writers who have spare time. If you're close with one of your users, even better.

Last year I knew one of the admins at my company who wouldn't mind my little experiment. She asked for a tutorial on an application, and I asked if I could observe her use the help for a while. I scheduled an appointment for an hour and then proceeded to sit at a nearby chair to watch her move through the documentation. Her task involved migrating her department's web content from single HTML pages to a new enterprise content management system.

As I watched, I realized more epiphanies in twenty minutes than I could gather from three months of editing the help on my screen. She skimmed the help while alternating her view from the screen to the help. She read quickly, and if she didn't immediately understand, she turned to me for help. On more than one occasion, she actually put her finger on the screenshots and lists and used them to confirm her place in the help. Every five minutes, she was distracted by a phone call or a someone's request and would have to stop the task. When she returned, she lost her place in the help.

Anytime you can borrow someone for an hour to watch them use your documentation, do it. The activity will show you the weaknesses in your help better than any other technique.

Also, observing users live is preferable to merely asking for feedback. I've noticed that when I give others documents to test, the feedback is usually mild. They say, "It was fine; I didn't have any questions except I noticed this needed bold formatting," etc. But if you watch the person, you can see their moments of struggle when they sit there trying to figure out what your document says -- and where they're supposed to click. You can see if they actually perform the task correctly as well. (You'd be amazed how people click erroneously with no idea they're doing things in an unintended way.)

Conclusion

These ten techniques can be powerful ways to connect to your audience. It's not always possible to implement them all, and every situation has its own needs. But I'm convinced that knowledge of user behavior is one of the most important aspects of technical writing.

Here are the ten tasks in summary. You can pin them up next to your computer and check them off as you attain each one.

10 Ways to Gather Feedback from Users

- Create a Send Feedback Link in the Webhelp

- Track Help Usage with Analytics Tools

- Monitor Support Center Call Logs

- Observe Users in Their Environment

- Contact Users Periodically

- Build User Profiles/Personas

- Establish Regular Communication Through Biweekly Tips

- Become a User of the Product Yourself

- Create a User Council

- Watch a User Try to Perform the Tasks in Your Documentation

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.