Best Practices for Writing Interface Text [Organizing Content #24]

In this ongoing series on organizing content, we've shifted from organizing help outside the interface to organizing help inside the interface. Moving help inside the interface has many advantages, and there are plenty of best practices for style and format. But the biggest shift in perspective, which I argued in my last post, is to stop differentiating between the interface and the help content. The interface is mostly text. It is an orchestra of words on a page that users rely on to navigate and understand the application's content.

The first step in organizing help content is to refine the existing words on the buttons, tabs, labels, and dialog boxes. When those words aren't enough, you can supplement the interface with more text to help users achieve their goals. Some technical writers refer to this supplementary text as narrative text, others as instructional text.

I don't have a specific methodology for reviewing interface text. I've reviewed hundreds of student essays in my time, and despite the rubrics that departments dream up to objectify and standardize the review, rubrics always fall short for me. They're an afterthought to try to organize your thoughts. I typically just read through a text and have a general reaction to it. Despite my resistance against rubrics, my thoughts on reviewing interface text can be grouped into five general areas: clarity, position, brevity, convention, and informativeness.

Clarity

In looking at the words in an interface, pay attention to your gut reaction. Where does it not feel right? Are there phrases or words that jump out at you as being off? Oftentimes the interface fails to use the right word to describe an action or concept.

As I mentioned in my Technical Writer as Outsider post, determining what's clear and what isn't clear becomes problematic if you're an insider to the product, having attended countless meetings discussing every aspect of the application's terminology and design from the beginning.

Even if you're an insider, as you look closely at the text in the application, read it carefully and analytically. Try to misinterpret it. See it as a new user might, and wipe away all your assumptions. What information is required to understand the sentences or labels? Where do you think users will become confused? Focus on these problem areas first. Replace obscurity with clarity. Switch clunkiness for plainness. Strip away fuzziness with accuracy.

In a culture of scanning and skimming, it's easy to become desensitized to poorly constructed sentences and imprecise meaning. But when we put on our language glasses and look closely at each sentence and word to analyze its meaning within the context of the screen, we start to see the gaps more clearly. Knowledge of grammar and style is helpful in heightening awareness, but as Chris Atherton points out, even reading good writing can make your literary senses more acute. For example, after reading this psycholinguist's essay -- They get to me -- about her love affair with pronouns, you'll start looking more carefully at the words you use in your sentences.

Position

Clarity isn't just a matter of choosing the right words. Clarity also comes from putting the right words in the right places. Proximity increases clarity. The text you add should appear next to what it describes. Mike Hughes expands on this idea and says that users are drawn to action points on a screen. He recommends putting the text just a little "downstream" of the action point. In one of the best essays on user interface text, Instructional Text in the User Interface, Hughes argues,

User assistance occurs within an action context—the user doing something with an application—and should appear in close proximity to the focus of that action—that is, the application it supports.

In other words, position your help text next to the place on the screen where the user performs the associated action the help text describes.

Hughes says users usually skip static text positioned away from points of action. Their line of focus moves straight to the actions they can do on the page. The Microsoft Developer Network also echoes Hughes' point:

Users tend to read control labels first, especially those that appear relevant to completing the task at hand. By contrast, users tend to read static text only when they think they need to. (User Interface Text: MSDN Library)

Practically speaking, you can forget about users ever reading the static paragraph that you add below the page title. They'll move right past it as if it wasn't even there and instead focus on the buttons and other actions they can do on the page. Add your help text next to those action spaces.

Brevity

If there's one undeniable principle in crafting interface text, it's brevity. Interface text needs to be as brief as possible for two reasons: users tend to skip over large chunks of text, and the available real estate for help content on the interface is extremely limited. About all you have available is a tweet, or 140 characters. One tweet per screen, if you're lucky. "Too much text discourages reading," MSDN says. "The eye tends to skip right over it—ironically resulting in less communication rather than more."

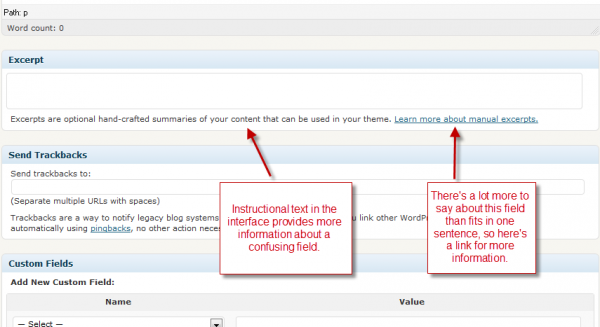

Because space is limited, you may need to provide a link to more information. A small help icon or link next to a point of confusion doesn't tire the eye and allows you to expand on a topic without rigid space constraints. The help link can open a pop-up window in an online help or just provide a pop-up within the interface itself. The following screenshot shows how WordPress handles interface text for the Excerpt field, which appears below each post you write.

Keep in mind that while your users may appreciate copious on-screen text the first time through, seeing the same abundance of text every time they perform a task on the screen can begin to clutter their view. This is one reason to use help links that open up more information: the help information only appears for those readers who need it.

Convention

Follow convention as much as possible. Your users have a history of expectations built up from thousands of hours of web browsing and application use. Users expect certain conventions that should probably be consistent in your application as well. Put the help button in the upper right. Use the standard names for buttons and labels, such as Save and Print.

One of my colleagues tells me that on one of his projects, the designer has decided to call the home button "Front" instead of "Home." I'm not sure why. Following convention may seem a bit boring, but it decreases the learning curve for users. It's one of the reasons Adobe tries to standardize their toolbars and interfaces across all their creative suite products -- so users can carry over learning from one application to another.

When you're stuck on names for buttons or other interface text, consult applications of a similar kind. For example, I was recently stuck on a button label in a calendar application I'm documenting. What word briefly describes the act of deleting "the current event and all subsequent events"? I checked out Google Calendar to see what term they used. While I didn't use their exact term -- "All following" -- their usage helped me come up with a better solution.

Informativeness

One of the greatest challenges in editing interface text is locating all the messages tucked away in the dark corners of the application. Most often this hidden text appears as uninformative or illiterate error messages programmers have either written or ignored as they coded the application.

For understandable reasons, error messages slip by most checkpoints and make their way into production because they are hard to find. Many writers never see these messages unless they're abusing the application. And once they appear, it's hard to remember what you did to trigger the message. My favorite error message is "Object reference not set to an instance of the object." This message seems to be pervasive across all .NET applications I've worked with. Though I've read and re-read this message dozens of times, I have almost no idea what it means.

How do you find all the messages in an application? How do you make sure you haven't missed an error message, or an email notification, or an ungrammatical success message? Just because you don't see it on the interface doesn't mean the text isn't there.

Sometimes programmers have a file that contains all of the language in an interface, especially if the application will be translated. Other times the messages are scattered throughout the application code. Quality assurance is no doubt aware of many of these messages, since they try to purposely break the application.

However you find the hidden text, when you do uncover one of these nuggets, they tend to provide golden opportunities for editing. I have rarely seen an error message or other notification that was informative. Usually these messages are phrased with as much obscurity and generality as possible. Programmers are sometimes careful to express in euphemisms what would otherwise be an admission of ignorance. Instead of "I don't know why this error occurred. Sorry, maybe we'll fix it someday," users see "Unhandled exception has occurred in the application."

Other times the reasons for the error are too complicated to explain in human terms. So we end up with "The conversation ended, or timed out, or resulted in a null exception." It may be accurate, but it's gibberish for users.

In Avoid Being Embarrassed by Your Error Messages, Caroline Jarrett recommends writing error messages in a way that tells users how to fix the problem. Piggybacking on Rhonda Bracey's advice, Jarrett says,

... Try to give users some hint about what to do next, such as: Please try again, switch everything off and on again, jiggle the plug, uninstall the software, or whatever.

Jarrett cites an example. She says one writer changed a message from "Low Voltage Error" to "Check Power Cable." The revised message focused on the fix rather than the problem and resulted in a "reduced support calls and certainly improved user confidence." By focusing on the fix, you can make your interface text more informative to your users.

I've only scratched the surface with interface text. But if you stick with these five areas: clarity, position, brevity, convention, and informativeness, you'll have a good starting point for improving interface text.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.