Unconscious Meaning Suggested from the Structure and Shape of Help

I'm continuing to make my way through James Kalbach's book, Designing Web Navigation. In chapter 2, he says the structure and format of content helps users anticipate the meaning of the content. He writes,

The human visual system naturally seeks structure in information, often very rapidly. Scientists refer to this as "pre-attentive" processing. This occurs in such a way that interpretation of a display is determined by the design itself. People can therefore infer relationships between elements on a web page before actively reading the page. This sets the stage for subsequent interactions. (p. 39)

We do this pre-attentive processing all the time. As an example, Kalbach says if you were to format a telephone book entry as a dictionary definition, users would assume the content was a dictionary definition rather than a phone list. Similarly, if you were to replace the telephone list with a lot of Xs rather than real content, users would still guess the list referred to telephone numbers, because the structure and format of the content suggests its meaning.

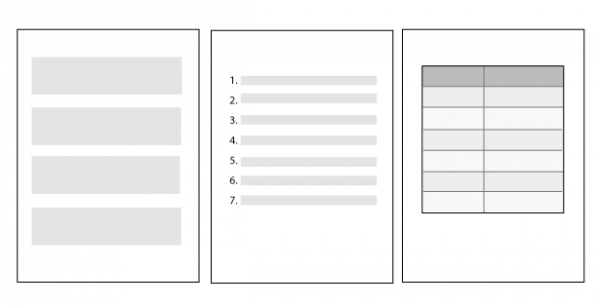

Here's another example, more related to help content. Based on the shapes below, what kind of information you would find in each one?

Did you guess that the first shape would explain conceptual material, the second, how-to instructions, and the third, reference information?

DITA has a strong influence in this area. Help topics typically fall into three main formats: concept, task, and reference.Rob Hanna, in his presentation on Information Ecosystems, says these three formats roughly reflect a beginning (concept), middle (task), and end (reference) pattern, so in that sense, DITA ties in with a larger story archetype.

Styles and preferences vary here, but in general, concepts are formatted in paragraphs, tasks in lists, and references in tables. When readers see information in paragraphs, they know the information will explain conceptual information. When users see a numbered list format (1, 2, 3), they know the information will contain sequential instructions for doing something. When readers see a table, they know it contains reference information.

Minimalist style enforces this shape of help. In minimalist style, task topics don't have any introductory paragraph information at all, except for one or two sentences. As a result, after the topic heading, you dive directly into the numbered list. Here's an example:

Add new posts

- In the Dashboard, go to Posts > Add New.

- Type a title and add content in the body of the post.

- In the sidebar, select a category and add descriptive tags for the post.

- Click Publish.

This task does not explain when or why you would create a new post, or SEO strategies for posts, or what kind of content you might explore in the posts you write. That information would more suitably fit a concept topic. Instead, you jump directly into the list of steps, without even a stem sentence to introduce the list (such as "To add a new post:").

In contrast, here's a concept topic:

About posts

If you want your blog to be visible and read, you need to publish posts on a regular basis -- usually about three posts a week. This can require a good deal of time, sometimes two or three hours per post. This time can easily add up to a part-time job, taking you away from time you might otherwise spend with your family, exercising, or developing other talents.

Because blogs require the same amount of time as a part-time job but often don't pay much in return, you should explore topics on your blog that you find personally enjoyable. The compensation should be writing itself and the enjoyment that comes from creatively exploring topics you care about.

To find what you're passionate about, consider answers to the following: what do you read/do/think about in your spare time? What direction do you want to be moving in your career? Remember that regardless of the topic you choose, you'll most likely fall back to writing about what you know. If you're involved in writing help documentation all day long, you'll probably have a lot to say about documentation strategies on your blog.

This can be both a good thing and a bad one -- good because your experience gives you a foundation of content to explore, bad because you may be tempted to write only what you know, rather than exploring unfamiliar but potentially more rewarding topics.

You're soaking in the concepts, right, without any expectation to actually follow a series of steps. You could have guessed that by merely glancing at the format rather than reading it.

Finally, here's a table format:

Rich text editor reference

The following buttons appear in the toolbar when writing new posts.

Add Media Allows you to upload photos and other media, resizing the uploads in the three sizes set in your Media Settings page. Blockquote Indents a paragraph of text, usually setting it off in a graphically appealing way. Align buttons Aligns text right, left, or center. If you're trying to align an image, don't use these buttons. Instead, use the image classes in the picture editor. Insert More Tag Breaks a post into two parts, with the first part shown on the home page. The second part is visible when users click the post title and view the post in the single post view. Strikethrough Puts a line through content to show that the content is no longer valid. Bold, Italic Formats the content as bold or italic. The tags added are <strong> or <emphasis> rather than <b> or <i>. This provides more information about the semantic nature of the tags. Toggle Spellchecker Spellchecks your content by adding a red squiggly line under words that are misspelled.

Mixing content types

It seems rather straightforward to organize help like this, but content does get more complicated. Suppose you have a two-paragraph conceptual explanation for a topic. Do you separate this conceptual information into its own concept topic? If you leave it in the concept mixed in with the task, does this mixing of structures make it more difficult for users to anticipate what the information will cover? Here's an example. Quickly glance at what follows and consider whether the structure lets you know what the content is about:

Writing posts

If you want your blog to be visible and read, you need to publish posts on a regular basis -- usually about three posts a week. This can require a good deal of time, sometimes two or three hours per post. This time can easily add up to a part-time job, taking you away from time you might otherwise spend with your family, exercising, or developing other talents.

Because blogs require the same amount of time as a part-time job but often don't pay much in return, you should explore topics on your blog that you find personally enjoyable. The compensation should be writing itself and the enjoyment that comes from creatively exploring topics you care about.

To write a new post:

- In the Dashboard, go to Posts > Add New.

- Type a title and add content in the body of the post.

- In the sidebar, select a category and add descriptive tags for the post.

- Click Publish.

Many people write help this way, mixing the two. But I believe it's generally a bad practice. Dividing the two would make the forms clearer to the reader.

About posts

If you want your blog to be visible and read, you need to publish posts on a regular basis -- usually about three posts a week. This can require a good deal of time, sometimes two or three hours per post. This time can easily add up to a part-time job, taking you away from time you might otherwise spend with your family, exercising, or developing other talents.

Because blogs require the same amount of time as a part-time job but often don't pay much in return, you should explore topics on your blog that you find personally enjoyable. The compensation should be writing itself and the enjoyment that comes from creatively exploring topics you care about.

Write a post

- In the Dashboard, go to Posts > Add New.

- Type a title and add content in the body of the post.

- In the sidebar, select a category and add descriptive tags for the post.

- Click Publish.

Heading formats

The structure of headings poses more questions as well. The structure of a task topic differs from a concept topic in the verb tense of the topic. For the concept, I wrote, "About posts," and for the tasks, "Add new posts."

Using the gerund form would be more ambiguous. For example, does "Writing posts" address a task or concept? By adding the word "about" or "overview" in the topic, it helps identify the topic as a concept.

As far as reference topics are named, I don't have a clear style defined for this, but I would probably use a form similar to concept topics.

Your feedback

I am interested to hear how you organize and name your help topics based on these three types of information. Do you have a clear way of styling verb tenses in your topic titles? Do you set off concept topics with "About" or "Overview"? Do you allow a few sentences before the task begins, or do you always put conceptual information into its own topic?

And if you always keep concepts separate from tasks, do you divide these two kinds of information into separate table of contents entries, or do you stack them together in the same topic under different headings?

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.