Tech comm trends: Providing value as a generalist in a sea of specialists (Part III)

- Opportunities related to doc tools and processes

- Incorporating structure into content

- Using specifications

- Your reactions and input?

Opportunities related to doc tools and processes

Doc tools and authoring/publishing processes are an area where tech writers can provide significant value. Although tech writers are typically generalists with the subject domain, they tend to be experts with documentation authoring and publishing processes and tooling. Tech writers can transfer the content that specialists write into more advanced tools or processes that allow for content re-use, stylized formatting, professional display, responsive design, and more.

When I first started working in my group at work, one of my tasks involved transitioning our authoring and publishing process from an outdated web CMS into a docs-as-code solution (using Jekyll) that would build from the command line. To create the Jekyll theme, I used Bootstrap to create the layout and styling of the docs. I also created a number includes (or reusable templates) to facilitate alerts, images, glossary tooltips, and more. I collaborated with other teams to create an end-to-end publishing solution that allowed our tech doc solution to scale. In fact, several other teams use our solution, and authors are able to just plug in and start writing docs without building their own solutions from scratch. For more, see Case study: Switching tools to docs-as-code.

Whatever your publishing solution, you can pretty much bet that the engineers in your group will have little input or understanding (and even less desire) to handle the publishing aspects of documentation. And yet, no one wants docs to look unprofessional. No one wants to deliver a Word file or PDF to customers.

Doc tooling and processes are a big topic, and I don’t want to suggest that every tech writer needs to be a tools support team. I’ll limit the scope here by drawing attention to two specific areas within authoring processes where tech writers can add significant value: structure and specifications.

Incorporating structure into content

One of the strategies in publishing is to separate content from presentation by extracting the content into a structure. This is a technique that is often lost on specialists when they write. When you extract content into a predictable structure, you can more easily manipulate the display/presentation.

In his new book on Structured Writing: Rhetoric and Process, Mark Baker says:

The aim [of structured writing] is not to eliminate complexity altogether – that is impossible – but to partition it so that each part of that complexity is handled by the person or process with the knowledge, skills, and resources to handle it. (xxi)

In other words, when you separate content out into its own structure, you can then turn up the complexity dial on the display because you’re no longer manually coding all the display logic with each page. You’re programmatically rendering this display from a simple data source. (Basically, you won’t get lost in div soup.)

For example, one topic in my docs is the Fire TV device specifications. This is actually the most viewed page in our entire doc site by a wide margin. Originally, this page was formatted as a table with various columns for the devices.

As the number of devices increased, the table layout no longer worked because I couldn’t have 12 columns and require users to scroll horizontally (a design atrocity that is often committed regularly in internal wiki pages).

I decided to extract all the specification information into a YAML file and then create a template that pulls information from the YAML file in programmatic ways. The code loops through each device in the YAML file to populate its own table, and also incorporates show/hide logic with a drop-down selector.

Here’s the YAML. Updating the information on the page basically involves just adding or adjusting entries in this simple YAML file:

media_specifications:

video:

h265:

ftvcube: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p (4K) @ 60fps...

ftvgen3: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p (4K) @ 60fps...

ftvgen2: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p (4K) @ 30fps...

ftvgen1: Not supported

ftvstickgen2: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftvstickbasicedition: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftveditionelement: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p (4K) @ 60fps...

ftveditiontoshiba4k: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p (4K) @ 60fps...

h264:

ftvcube: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p @ 30fps...

ftvgen3: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p @ 30fps...

ftvgen2: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftvgen1: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftvstickgen2: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftvstickgen1: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftvstickbasicedition: Hardware accelerated up to 1080p @ 30fps...

ftveditionelement: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p @ 60fps...

ftveditiontoshiba4k: Hardware accelerated up to 3840x2160p @ 30fps...

...

This approach has dramatically simplified the creation and maintenance of specification info, as I don’t have to try to maintain the consistency of formatting and styles across 12 different discrete tables. I created a sophisticated display component that lets users select the device they want to see, and all other information that applies to other devices gets hidden. Check it out here.) For fun, view the source code. You’ll see that if one had to manually code the HTML on that page, it would be a nightmare, prone to all kinds of errors.

Further, when I want to include the same specification info on other doc pages, I can pull the information from the single specification source. For example, I pushed some select and relevant info about devices into another page here, pulling the content into navtabs with dropdowns. Pulling from the same source removes redundancy and risk of error. (For more technical details on how to manage this in Jekyll, see this post on handling device specifications on the same page.)

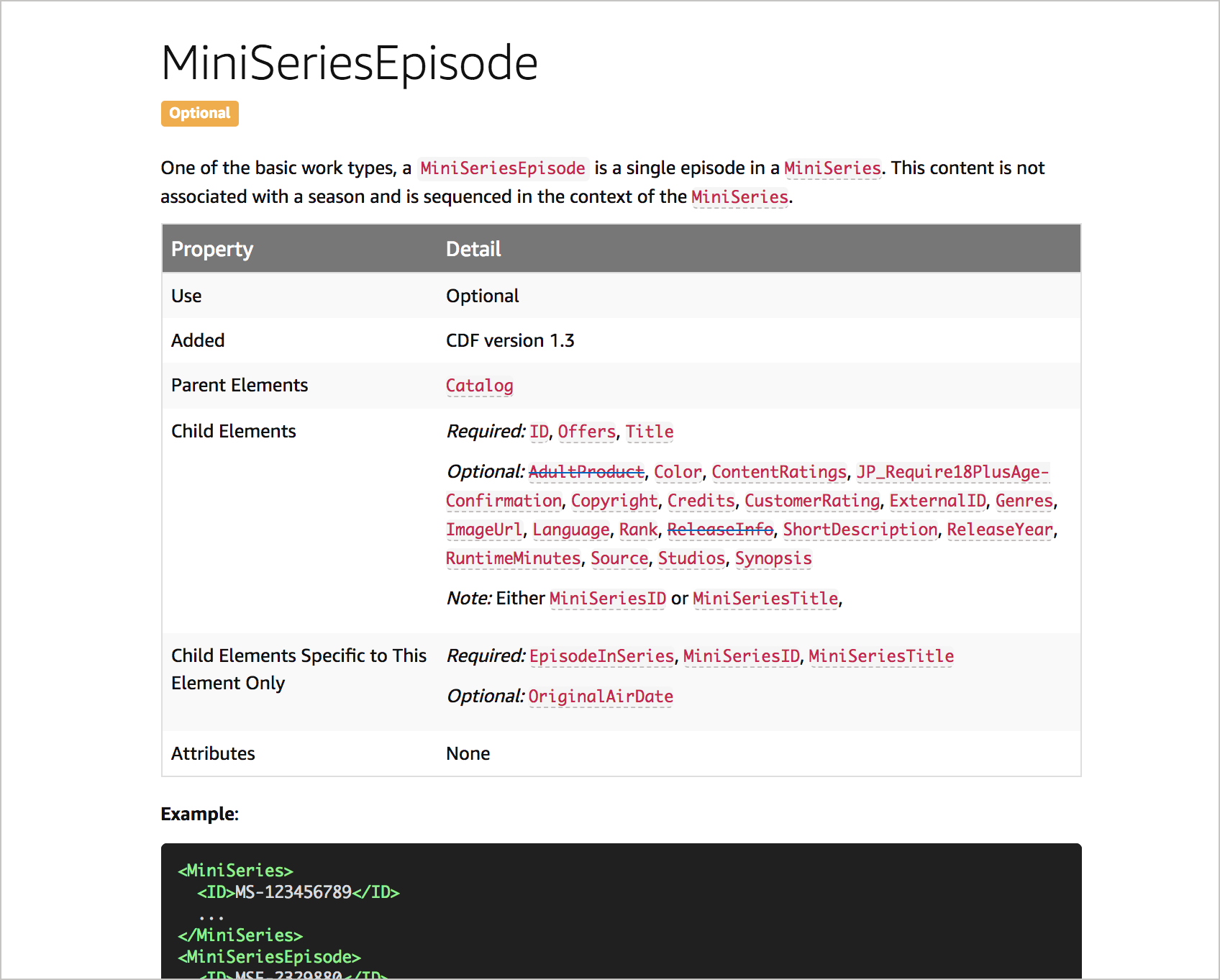

There are lots of different ways to introduce structure into docs. Here’s another example. We have a schema for creating a catalog file. This schema includes about 75 different elements. I wanted to separate out the source content from the display, so I looked at all the different fields we were capturing for each catalog element. I came up with a YAML schema that looks like this:

ElementName:

anchor: string

description: >

string

required: boolean

added: string

deprecated: string

parent_elements:

- name: string

deprecated: boolean

child_elements:

required:

- name: string

deprecated: boolean

optional:

- name: string

deprecated: boolean

this_element_only_required:

- name: string

deprecated: boolean

this_element_only_optional:

- name: string

deprecated: boolean

child_elements_notes: string

child_elements_this_element_only_notes: string

attributes:

- name: string

accepted_values:

- value: boolean

description: string

required: boolean

accepted_values: string (if empty, [])

example: |

code...

I then stored all the catalog elements into this YAML schema. After that, I created a template to iterate through the information in the YAML file and render it into a display (you can see the output here.)

Again, this approach dramatically simplifies the authoring and editing of catalog information, because I no longer need to worry about the display, having defined it in the template.

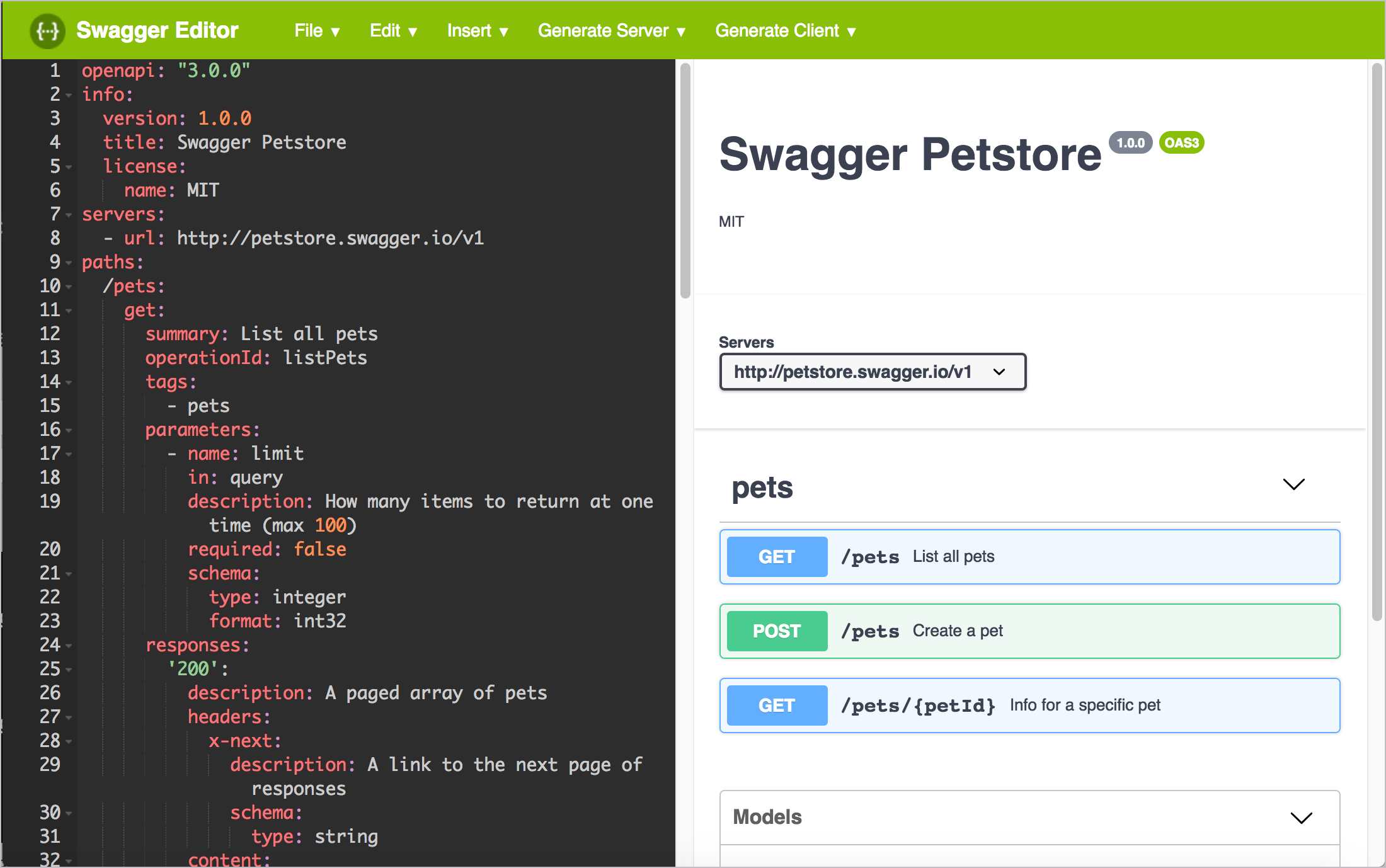

Using specifications

Specifications are just a structure that has been adopted as a standard. One application particularly relevant to API design is the OpenAPI specification (aka Swagger), which is a standardized way of describing a REST API that follows a specific JSON or YAML structure. Most developers I’ve worked with have little knowledge or understanding of OpenAPI or its benefits.

When developers create a new API, they often start drafting all the details in a wiki page, often with a massive table that scrolls horizontally in unwieldy ways. Few developers are aware that there’s an entire specification developed for web APIs — the OpenAPI specification.

By understanding this specification and how to implement it with REST APIs, you can provide a number of benefits to specialists. First, you can help them embrace a spec-first design philosophy, where APIs are designed and tested before being coded. Second, you can generate interactive docs that let users try out requests and see responses for their own data, which tends to be more instructive. Finally, you can align the information in an industry-standard presentation that makes sure you cover all the expected areas of documentation and present them in predictable ways.

Even if you’ve simplified your doc authoring and publishing toolchain with more simple formats like Markdown or wikis, you aren’t limited to primitive publishing techniques. You can look for ways to extract the content into helpful structures and specifications that improve the efficiency and use of the information. This is one of the main ways that tech writers can add value in these specialist contexts.

Your reactions and input?

You can see the responses (so far) here.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.