Incorporating Learning into Tech Comm Deliverables

I recently attended an internal conference at my work for instructional designers. The focus of the conference (as I assume the focus is for many instructional design conferences) was on "learning." I always find the emphasis on learning in the ID crowd fascinating, because this is rarely a word that tech writers use, yet our goals are largely the same.

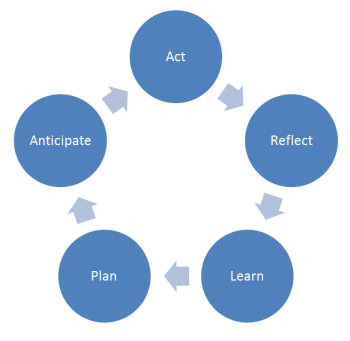

The keynote speaker presented a model for learning that included five steps:

- Act

- Reflect

- Learn

- Plan

- Anticipate

The Plan and Anticipate steps seem nearly the same. And I'm not sure step 3 is legit, because how can "learn" be a step in "learning"? But stick with me, because I really like the first two steps.

The speaker explained that this model of learning focuses on "action-oriented development." He admitted his bias about the importance of experience in learning. He also emphasized that unless we take the time to reflect on our actions, we don't often learn from our experiences.

Given that I don't include any activities for acting or reflecting in my help material, I mulled over this model for quite a while. By not incorporating these elements, am I excluding what would otherwise allow my users to learn? Why isn't learning a more important consideration for the way I develop my help material?

Attempts at Integrating These Elements

While I was about on lap 20 at the pool the other night, I realized how to integrate both the action and reflection components into help material.

The first component, Act, can be incorporated by including some sipmle practice activities below tasks. This is not difficult by any means. If you can provide a sandbox environment for users to explore, all the better.

The second component, Reflect, requires more tact. I don't think I could incorporate reflective questions in a help topic without sounding corny (e.g., How did creating a new widget make you feel? What did you learn from your experience in adding a new administrator?)

However, if we alter the reflection element a bit, changing it to "Real Scenarios," it sort of works.

Mark Baker recently wrote a post that's relevant to this point about reflection. His post, The Real Docs Need Is Decision Support, talks about the need to go beyond technical instructions and instead provide users with decision-making information for real business scenarios. Mark writes,

My field is software development, after all, and not everything in the software development world is done through a GUI. For programs, scripts, and command lines, the mechanical details of command syntax have to be clearly documented. But even where documentation of mechanicals is required, it is never enough. The real tough parts of these tasks are the decisions, large and small, that have to be made along the way — decisions as large as whether and when to do the task at all, to as small as how to choose the right value of an individual field or parameter.

Perhaps the reflection component, so critical to learning, could be included as an exploration of how to apply the technical knowledge to real business scenarios? The basic outline of a help topic might look like this:

- How-to Steps

- Practice Activities

- Real Scenarios

For example, instead of the corny questions I posed above, I might ask the following:

- How can you use this widget during the sales cycle to reduce communication overhead?

- How many administrators might you want to designate to help keep the data up-to-date?

I'm not sure that merely asking the questions provides the business decision support information that users might need, but it's a step in the right direction. (Perhaps a real rather than fictitious scenario might be easier to model.)

Why Help Fails

Mark's post emphasizing the need for business information hits on the findability theme I've explored on my blog at length. If users need business specific information, not just technical how-to instructions, then their searches for this information will fail if the help doesn't include this information. Help will end up being a set of mostly obvious topics (except to tech novices) that fail to have any valuable information.

We talk a lot about different techniques for findability — including indexes, glossaries, organizing the content well, etc. But the largest factor in that equation is the content itself. If the content doesn't address the real questions users have, it doesn't help users. They won't find their answers in the help because the answers aren't in the help.

Why We Omit Business Information

Why exactly do we omit this kind of business information? Because it's hard to write. I once worked on a sophisticated traveling/scheduling application that had an accompanying binder written by the department's secretaries detailing very specific procedures and workflows that weren't part of the application's functionality. Information such as, send "John" a reminder e-mail once you put the report in his inbox," or "The information must be included in the Y report and sent out on Monday; then wait a couple of weeks for it to process," and "Betsy is the one who processes this information and you can call her at 2-5555 with any questions," or "The yellow sheet at the back is the only important information in the report...."

That kind of stuff. I said I'd have to move in to their department and live among them for a few months if they wanted me to document their business process. (I never did.)

In a previous job, I wrote documentation for financial analysts. One time I remember documenting a short sale analysis application. Not having a Series 7 license myself, I found a lot of the concepts difficult to understand. I was grateful enough to correctly document how the application worked. But expanding the help to include advice on short sales and stock trading scenarios as it applied to the application's tools would have been somewhat miraculous. Although it would have been great to include this information, doing so would have required a lot more knowledge than I had.

In short, we omit business information because this kind of information is hard to figure out. It's often specialized to a specific group or industry, and it changes periodically. It's not something you can figure out by merely playing with the application on your own, which is how I like to discover a lot of the help information. You have to milk business relevant information from a SME, if he or she decides to explain it to you.

Additionally, business information for one group may vary for another group. If your application is used by a variety of people, from companies in Europe to non-profits in Canada, no doubt the business processes for each group vary. How then can you write relevant business specific information if this information is so variable?

Moreover, if you did start to expand the help with business information, don't you risk increasing the size of the help material to an undesirable length? The user who checks the help for information how to configure Widget X now encounters a 22 page chapter about all the uses of Widget X — but no instructions on how to actually configure it! (At least none that he or she can find.)

I still value and applaud the effort to include business decision-making information in help material; I just want to acknowledge the difficulty of doing so.

Why We Omit "Learning" Information

I started this post by talking about a model for learning, and then I veered a bit towards a discussion of whether to include business information, which some consider extraneous to the core material of help, while others feel it gives help a heartbeat.

Now let's explore why we often omit learning information — the reflective questions, the practice activities, the extensive scenario-based tutorials, and so on.

Going down this road to learning opens up the age-old question about tech comm versus instructional design. Current trends in tech comm encourage writers to adopt a minimalist style. Include only the bare minimum of what the user needs. Stop glucking up your help with all kinds of conceptual explanations the user doesn't want. Get rid of stem sentences as well. Just cut all the fluff and focus on quick, easy, task-based steps, because the user doesn't want to spend time in your help material. The user wants to go in, get the information, and get out. You have about 10 seconds to let the user do that before his or her patience and frustration reach their threshold.

With this minimalist mentality, is it any wonder that we skip the learning objectives, practice activities, and reflection questions? All of these learning components assume the user has a lot of time and nothing better to do than to explore all the modules and exercises and scenarios and question-based activities in your help material. Sure all of this leads to "learning," but the user is so eager to be done with help that learning gets shelved for more time-efficient action.

As an example, have you ever wondered why the instructions for the 1040 EZ tax form don't include any activities for learning? There aren't many practice activities or reflection questions, even though such material would help me learn to do my taxes better. No, those tax instructions are already 40+ pages in length. Who wants to extend them even more, converting them into a homework-like workbook? Only someone who is considering a tax emphasis in pre-law might think this is a good idea.

This leads to the question: what sort of users have time to learn? Few people look forward to going into a Learning Management System (LMS) to complete a course. I currently have a three-week-old invitation waiting for me to complete the yearly security awareness training, which will require me to sit through an LMS, proceeding screen by screen as I read quotes, answer questions, consider the right choice for fake scenarios, click response buttons, and get inspired by watching 30 second clips of leaders reading lines fed to them on a teleprompter.

Is it just the tech writer in me, or don't most people prefer a raw go at the information, a chance to read it and spit it out in a quick completion test rather than having to "learn" the material?

A while ago I sat through 20+ minutes of excruciatingly long e-learning for a Boy Scout volunteer requirement. The e-learning was well done, with video scenarios, periodic quizzes, short things to read, and decisions to make. Throughout this 20+ minutes, I was probably learning a great deal more than I would have if I'd just read the same information. The e-learning techniques were no doubt searing into my brain the importance of "two-deep leadership" and how no leader should ever be alone with the boys.

Well, after I painstakingly "learned" all of this material, it turns out I couldn't complete the quiz at the end because I had used a tablet device to view the video, so I had to replay the whole thing again in the morning on a desktop computer and "re-learn" the material once more. (By this time I was just gaming the system and using Alt-Tab to multi-task between video segments.)

I don't mean to be so hard on learning. There are times when I'm in the mood to learn. One time I wanted to learn Visio and stumbled across an excellent tutorial from Microsoft (and raved about it in a post). Doing all the practice activities really did help me learn the application. The key difference, though, was that I was in a mindset to learn. I had set a goal to learn a new application, and with that goal, I found time to stop whatever I was doing, sit down, and carefully learn.

But unless the user wants to learn, including learning activities seems only to get in the way of the user's main goal: to get information quickly.

Conclusion about Learning and Business Information

Although including business information and learning activities into help can be worthwhile, doing so poses a number of challenges. It can be difficult to gather the business information, especially if you're not an expert in the field. The business information may change radically from group to group and quickly become outdated.

Including learning activities may help users who want to sit down and learn, but this mindset rarely describes the typical user of help, who is often frustrated, at her wits end, and eager to complete a time-sensitive task.

As a result, although expanding help with both business information and learning activities may be appropriate in some contexts, more often than not this extra material is something we don't have time to write.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.