What I learned in using AI for planning and prioritization: Content strategy might be safe from automation

- Planning and prioritization tasks

- Inputs to consider when doing doc planning

- Correctly identifying priorities

- Cycling in important-but-not-pressing tasks

- The experiment

- Step 2: Create a list of planning and prioritization rules

- Step 3: Run the analysis

- Results

- Analysis

- The positives

- Quickly surveying research

- Conclusion

Planning and prioritization tasks

Although not often seen as a core tech writing task, I spend probably 10% or more of my time trying to figure out what I should be working on among a host of possible tasks and priorities. Can AI tools help with planning and prioritization? This is the question I explore in this post.

The short answer is basically no, AI tools aren’t that helpful with this task. This is actually a good result, as it points to an area that tech writers can focus on without the fear of it being automated by AI.

Note: Due to the limited availability of tools for this task, I wasn’t able to do the full testing I wanted to perform. As a result, this post is more theoretical than experiential.

Inputs to consider when doing doc planning

When doing planning and prioritization, you have multiple inputs to consider:

- Objectives at different levels: These objectives include company-wide objectives, department-wide objectives, group-wide objectives, team-wide objectives, and even personal objectives. Known by many different names, these objectives are often called “OKRs,” for objectives and key results. Theoretically, the OKRs should stack, with each level supporting the objectives above it, eventually rolling up to the company-wide objectives. This stacking provides coherence across the organization. However, in reality, the objectives rarely stack.

- Analytics: Analytics can identify the most popular content, content with potential usability problems, content with findability problems, least-visited content, and more. These analytics can inform priorities in some way. At the very least, a list of your top ten most popular pages should likely receive more attention than pages no one visits (unless the one visitor is a multi-million dollar partner).

- Release calendar: The release calendar identifies upcoming product releases (that require supporting documentation) for all the teams you support. Gathering release information is key to planning, especially because it identifies some of the lengthier documentation efforts that might take several weeks to complete. Minor doc tasks don’t usually appear on the release calendar, but those major product releases that often require weeks of documentation work do.

- Backlog of bugs: Almost every tech writing team I’ve worked on has 100+ bugs in the backlog, with different creation dates, severity, priority, and difficulty for each bug. The list of bugs is usually a miscellaneous list in random order. Some bugs were filed by tech writers, others by engineering teams. Some bugs might be old and no longer relevant, while others are still relevant but old and people seem to be getting by just fine as is.

Correctly identifying priorities

Beyond these inputs, you have to navigate misplaced priorities due to extra-vocal requesters. Just because a team makes a doc request and is vocal about fixing the doc issue, it doesn’t always mean you should prioritize it. There might be more pressing issues impacting users that are outside the requesting team’s priorities.

For example, suppose Issue A is resulting in many frustrations and failures for users, but the Alpha team isn’t responsible for Issue A. Instead, team Alpha has a huge upcoming release for a feature that, in all reality, isn’t even something users want. Team Alpha is riding you to create documentation for their upcoming SuperDuper Widget, and they’re invested in having you dedicate endless hours to creating the perfect docs. All the while, Issue A continues to discourage users and lose business revenue; users don’t have a clear way to relay the problems with Issue A to you.

It takes a lot of acumen and willpower to backburner Team Alpha’s request and focus on Issue A. Now multiply this kind of prioritization across 5 different teams, and you’ve got a real challenge. Suppose Team Alpha happens to be co-located with you, or is familiar with how to file docs, or even just has doc champions. That doesn’t mean Team Alpha’s projects are more important than Team Omega’s projects, or Team Zeta’s, or Team Beta’s, and so on. In short, you need an objective way of determining priority apart from the person who happens to be shouting the loudest.

Cycling in important-but-not-pressing tasks

There are also doc tasks that are important but which don’t map to any OKRs, aren’t things people are asking you about, and aren’t even user-facing bugs. These bugs could be scripts to automate doc generation and publishing, internal docs that define processes to follow, bug templates that require requesters to add necessary details when filling bugs, and so on. You have to cycle this work into the other doc work.

From all of these inputs, you have to decide what to work on. Ideally, you do this planning during sprint planning periods, which scrum-following teams tend to do every 2-3 weeks. However, in my experience, work rhythms are usually too dynamic to do this in a neat fashion. Incoming requests frequently disrupt and shift sprint plans. Additionally, it’s rare that I dedicate an entire day to auditing, labeling, and prioritizing bugs in a way that would facilitate proper planning. Even gathering analytics data, reviewing goals, and updating the release calendar are time-consuming tasks in themselves.

Here’s what usually happens: Every few days, I take out a clean sheet of paper and write down all the pressing tasks I have for the day or week. I draw a vertical line down the page and put all the work tasks under a title called work, and on the other side title it home and put all my personal tasks. About every 2 to 3 days, I repeat this process with a new piece of paper. It feels ridiculous and embarrassing to explain that this is my organization process, but it’s what I’ve been doing for 15 years.

Can we use AI to help with the planning and prioritization of doc work? Let’s see.

The experiment

Here’s my initial experiment to use AI for planning and prioritization.

Step 1: Make sure information is up to date

To experiment, I first needed to make sure all the information was populated online somewhere. If the task was in my head only, there’s no way AI could help with planning and prioritization. To make sure all information was noted, I did the following:

- Make sure bugs exist for the work. I looked through my email to make sure all doc requests were represented by bugs in the ticketing system. A lot of times, conversations start here but haven’t materialized into bugs yet.

- Audit all the bugs in the backlog to make sure they are current. For each bug, I tagged them with the product name and the priority. I also made sure the titles reflected the work.

- Make sure my team goals are up to date. I made sure our team goals were current. We make quarterly goals during a planning process, but they aren’t set in stone. They can also go out of date, get postponed, or be tasks that are already completed. If the tasks were completed, I marked them as completed so the AI tool didn’t factor them into the plans.

- Create a release calendar. Although many teams have release calendars to track product releases, sadly I wasn’t this organized and didn’t have one. To put together this release calendar, I would need to navigate our launch system for product launches; the problem is that not all teams use this system, so it’s not reliable to track all feature releases.

- Export the latest analytics. I should have exported our analytics, but I didn’t do this because I haven’t been monitoring my doc analytics lately.

Step 2: Create a list of planning and prioritization rules

In this step, I created a list of planning and prioritization rules for the AI to follow. How can the AI decide what’s a priority unless I’ve defined what a priority is? Here are my rules for priority:

- Prioritize bugs that are marked as P0 or P1 over P2, P3, and P4 bugs.

- If the task is large (meaning it will take more than 3-4 hours to complete), suggest breaking it down into subtasks.

- Keep time-sensitive tasks with due dates in mind. They might need to be prioritized more than tasks with no due dates.

- Group similar tasks to take advantage of similar momentum and context.

- Prioritize bugs that are related to goals (OKRs).

- Don’t prioritize bugs that are blocked due to incomplete prerequisite tasks.

Step 3: Run the analysis

After ensuring my information sources were up to date, I exported all the information into a single Google Doc and plugged it into Notebook LM.

Results

The results were pretty poor. It seemed to pick tasks at random. I made a number of queries here, trying different approaches, but it was clear that the AI wasn’t good at this. The responses weren’t anywhere close.

As I noted at the start, I’m limited in the tools I can use for this. I didn’t use Bard, ChatGPT, or Claude, which are my favorite AI tools.

Also, I don’t think my list of exported bugs had all the information the AI tool needed. For example, the product tags might not have come through.

I also tried to apply AI to help with planning and prioritization of my personal tasks, and for these experiments, I used more mainstream AI tools. But again, the AI responses disappointed me. I thought I could use AI to more intelligently plan my weekend tasks and tackle them efficiently and productively. But not really. The recommended breakdown of tasks was kind of dumb and unhelpful.

Analysis

This is a topic I’ll need to revisit when more liberal use of AI tools is allowed within the corporation, but I’m not optimistic. The problem is that planning and prioritization involve a lot of context and judgment. Not all of this context is explicit in the information the AI has to process.

If every bug were explicit about when it needs to be published, how it connects with the larger organization’s goals, who the reviewers are, what their timelines and team are like, and more, then perhaps AI would do a better job with planning and prioritization. But really the work of planning and prioritization is gathering this information. It takes many hours to cross-check bugs against upcoming releases and other support ticket priorities. There could be a future where this information is more readily available and can assist planning, but my initial experiments with AI here weren’t helpful.

Note that AI tools aren’t entirely absent in this area. There’s a new AI tool for goal planning called Summit: AI Life Coach. It’s more for personal goals, though, and I think it’s supposed to provide coaching and feedback about your progress. I played around with it briefly but didn’t feel inspired to try using it more intensively. I’m guessing that describing the progress toward my goals in a diary-like way and getting feedback could be valuable. The mere act of keeping a journal about my goals would be a great best practice that is likely a good system and approach for goalkeeping, as it would keep me focused and reflective. But that’s not AI, that’s just a goal journal.

The positives

Although this post might seem like a downer, it actually isn’t. The failure of AI to fully help with documentation planning and prioritization is actually a good thing, as it provides a potential area that can’t easily be replaced by AI. Perhaps content strategy is an area that opens up for technical writers to emphasize, in a more foolproof future way.

This is a topic I’ll need to explore in more depth. And obviously, my planning experiments were half-baked. But I think content strategy is a good area to expand on.

Quickly surveying research

A quick survey of research suggests that analytical thinking and complex decision-making won’t easily be automated by AI, especially compared to tasks such as writing. Here are a few sources that support this idea.

Kai-Fu Lee, author of AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, says “AI cannot create, conceptualize, or manage complex strategic planning” (10 jobs that are safe in an AI world).

In the Economic Times, Satyam Sharma says “Jobs involving high levels of human interaction, strategic interpretation, critical decision making, niche skills or subject matter expertise won’t be replaced by automation anytime soon” (Scared that ChatGPT will take your job? Skills or jobs that won’t be replaced by AI in future).

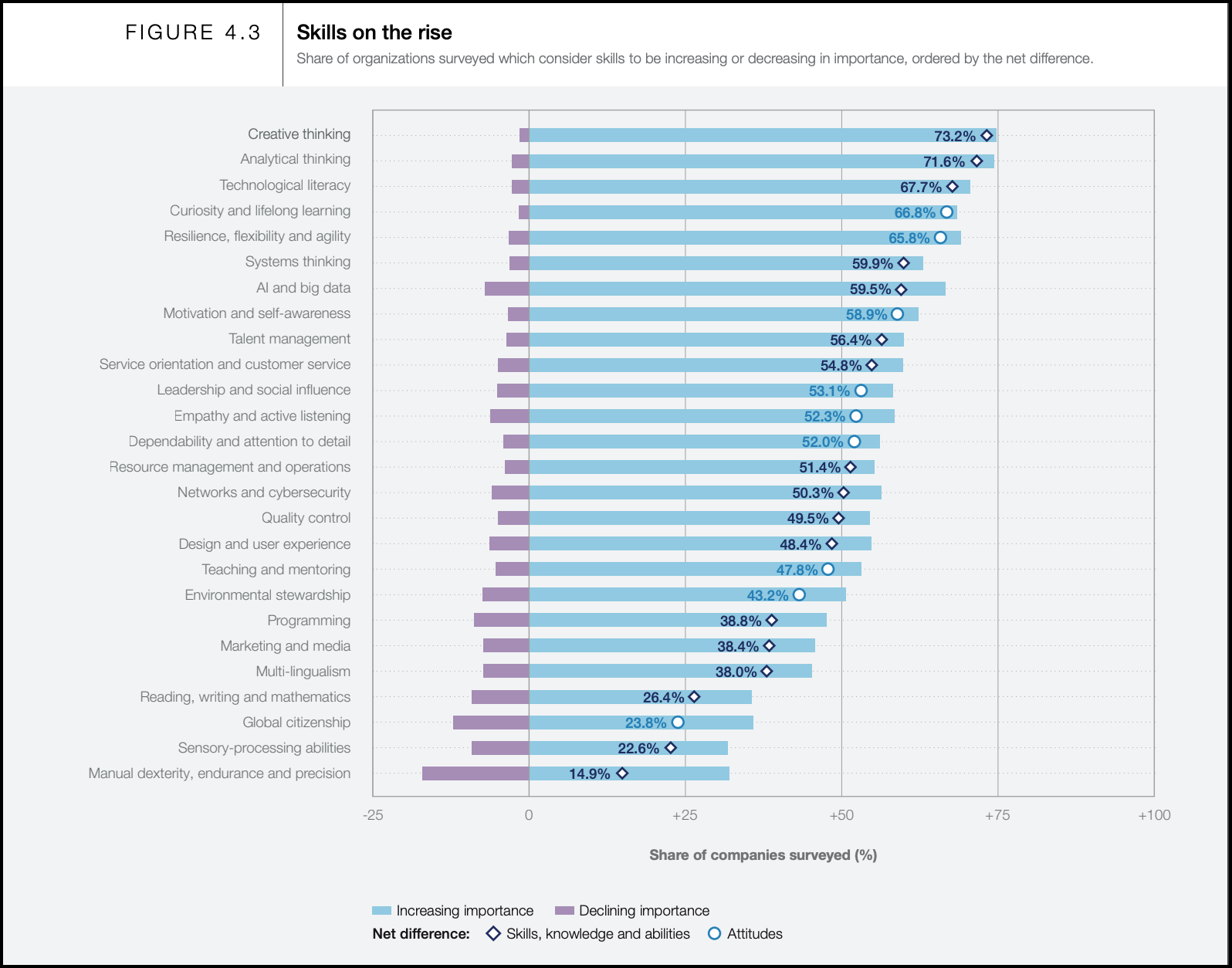

Moving on to more substantial sources, The Future of Jobs Report (May 2023), which highlights skills that will be in demand, notes:

Analytical thinking and creative thinking remain the most important skills for workers in 2023. Analytical thinking is considered a core skill by more companies than any other skill and constitutes, on average, 9% of the core skills reported by companies. Creative thinking, another cognitive skill, ranks second, ahead of three self-efficacy skills — resilience, flexibility and agility; motivation and self-awareness; and curiosity and lifelong learning — in recognition of the importance of workers ability to adapt to disrupted workplaces.

Here’s a screenshot from the report showing the high-demand skills (p.39):

In AI Isn’t Ready to Make Unsupervised Decisions (Harvard Business Review), Joe McKendrick and Andy Thurai explain that AI lacks human qualities like empathy, ethics, and morality that are important for real-world decision making. The article uses the “trolley problem” thought experiment to illustrate this — a human would make a more nuanced decision than an AI system focused solely on facts and data. The authors write:

Artificial intelligence is designed to assist with decision-making when the data, parameters, and variables involved are beyond human comprehension. For the most part, AI systems make the right decisions given the constraints. However, AI notoriously fails in capturing or responding to intangible human factors that go into real-life decision-making — the ethical, moral, and other human considerations that guide the course of business, life, and society at large.

More to the point, they also note that while AI can create content, it might not know what content humans want to consume, and it might have biases in selecting what type of content to create. In other words, AI can’t be left unsupervised from human direction and steering. The authors explain:

Notably, the technology can now create original text that reads as if written by humans. Advancements over the last few years, especially with Google’s BERT, Open AI/Microsoft’s GPT-3, and AI21 Labs’ Jurassic-1, are language transformer models that were trained using massive amounts of text found on the internet in combination with massive sets of data, and are equipped to produce original text — sentences, blog posts, articles, short stories, news reports, poems, and songs — with little or no input from humans. These can be very useful in enterprise tasks such as conversational AI, chatbot response, language translations, marketing, and sales responses to potential customers at a massive scale. The question is, can these AI tools make the right decisions about the type of content people seek to consume, more importantly produce unbiased quality content as original as humans can, and is there a risk in machines selecting and producing what we will read or view?

For example, with documentation, tech writers might pursue more proactive, decision-directed documentation rather than adopting reactive behavior in which they respond to doc requests only.

Even looking back a bit further, in a 2017 McKinsey report titled Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation, the researchers say strategic decision-making jobs are among the harder-to-automate occupations that will continue to be needed in the future, even as automation affects a substantial share of work globally:

Automation will have a lesser effect on jobs that involve managing people, applying expertise, and those involving social interactions, where machines are unable to match human performance for now.

Conclusion

Based on this quick survey of research, it seems clear that analytical thinking and complex decision-making are areas that will struggle to be automated. As technical writers, if we want to survive the AI wave and avoid layoffs due to automated bots that can suddenly write all the docs (for example, see CEO roasts human workers he fired and replaced with ChatGPT), then we might shift more into content strategy roles — the kind of strategy that involves analytical thinking and decision-making, not just content production.

This might mean focusing on documentation strategy more than documentation bugs, on meeting with key stakeholders to gather insights and analysis rather than just fulfilling requests to write docs, and synthesizing the right doc plans based on analytics, user feedback, and product roadmaps rather than just responding to product team requests to write docs for their next release.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.