Diversity in tech comm -- Conversation with John Paz

- Discussion articles and summary

- Getting to know you

- The access barrier

- The pipeline problem

- Networking hurdles

- Comparing Silicon Valley with other areas

- The hiring process

- Anonymity as a problem more than benefit

- Concluding thoughts

- About John Paz

Discussion articles and summary

As with other conversational posts, we start with some articles for discussion:

- Segregated Valley: the ugly truth about Google and diversity in tech

- Atlassian’s John A. Paz On Being A Technical Writer, A Young Parent, And A Fan of #BlackTechTwitter

Article summary: In these articles, the authors say that although many Silicon Valley companies aspire for more diverse workforces, they haven’t made much progress. In the top 75 companies, only about 3% of employees are black. Many Silicon Valley companies attribute the low percentages due to the lack of candidates in the pipeline, but they also insist on recruiting from elite colleges. Here’s a quote from the Silicon Valley article:

The representation of black, Latino, and female employees at top Silicon Valley technology firms remains so disproportionately low that a government report published last year described the problem with the same word that Jackson uses: ‘segregation’. For all its forward looking technologies, Silicon Valley is in many ways mired in the ugliest practices of the American past. . . . The DC area is a kind of mirror image to Silicon Valley when it comes to hiring African Americans. Overall, blacks make up 14.4% of the workforce nationwide and 7.4% of high-tech employment. In the DC metro area, which includes parts of Virginia, Maryland, and West Virginia, blacks hold 17.3% of the jobs in 12 computing occupations, according to government employment data. But cross over to the west coast, and in Silicon Valley African Americans hold just 2.7% of the jobs in the same categories. At premiere employers like Google and Facebook, black representation in technical jobs drops below 2%.” (Segregated Valley: the ugly truth about Google and diversity in tech)

For a more current article that reflects what many tech firms are currently doing, see Tech firms say they support George Floyd protests — here’s what’s happening. However, the underlying under-representation as described in the original Silicon Valley article still remains.

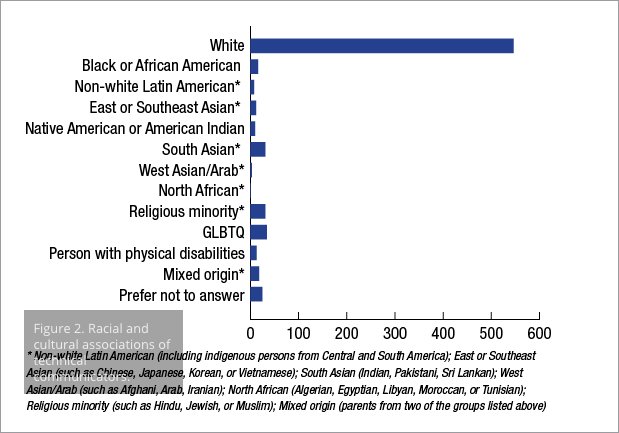

The current protests and other efforts for reform, along with this article and the tech comm profession’s demographics, prompted me to reflect more about ethnic diversity in tech comm. Looking at the demographics of the tech comm profession from Data USA, it shows that 84% of technical writers are White, 7% are Asian, and 6% are Black. This profile is similar to the findings in Saul Carliner’s 2018 Tech Comm Census, where he found that “Diversity appears to be a challenge in technical communication. Eighty-one percent identified as White. Association with other groups ranges from 2 to 5 percent.”

Getting to know you

TJ: Before we jump into the topic, I’d like to get to know you better. In this POCIT profile article, you mentioned that your mother, an English professor of writing and literature, steered you in this direction. Can you describe your story about how you got into tech comm, about how you identified that this career path was right for you? Also, what kind of work do you do at Atlassian? Can you share details about any projects you’ve worked on, or professional interests that excite you?

JP: My Tech Writing origin story: I always wanted to be a writer. As far back as I can remember I’ve been writing stories, poetry, and all kinds of things. It wasn’t until my wife and I got pregnant early in life that I considered Tech Writing, and even then it was pretty reluctant. My mother, an English professor, had her office directly next door to a Tech Writing professor. They were friends and spoke regularly and once I became a college student he essentially started to actively recruit me to the Tech Writing program at the University of Central Florida. I wasn’t sold.

But there was a specific moment when I could finally see myself as a Technical Writer and decided to give it a try. It was a flier on the Tech Writer professor’s wall, a riff on the old Jeff Foxworthy bit “You know you’re a Redneck if …,” but instead read “You know you’re a Technical Writer if …” and had a list of hilarious (yet accurate) character traits common to Tech Writers. Things like “bullet lists entice you,” and “you find yourself rewriting poorly written instructions, just because ….” That flier was an assignment done by someone who eventually became a very good friend, and President of the local STC chapter. It was enough to convince me to try the Intro to Tech Writing course, which I found came naturally to me. After spending my entire life trying to build complexity and nuance into my creative writing, Technical Writing wanted me to just write short, simple, direct sentences. Almost seemed criminal how easy it was for me, which was very fortunate. My wife and I were raising three kids while I worked my way through university.

One of the assignments in school was to create a professional resume and post it online, which I did, and got the attention of a tech recruiter. I went from working at Circuit City to being a legit contract Technical Writer for Siemens Power Generation in Orlando, and I had two years left before I graduated! I was in way over my head, but it was a turning point in my family’s history.

Until then, we needed various government assistance to make ends meet. The Siemens job was a blessing and a curse, because while I did essentially double my take home pay with one job change, it meant we no longer qualified for the government benefits we depended on to make ends meet. It was a hard introduction into the middle-class squeeze.

I found out soon how in-demand Tech Writing was, as I was regularly getting contacted by recruiters for different jobs, and worked as a contractor for a few years at some of the biggest tech employers in the Orlando area. Most of those jobs were with defense contractors like Lockheed Martin, but I also did a stint at EA Sports, which seemed like my dream job at the time.

Once I landed my first job at a high tech company, I realized that’s where I wanted to be. I worked on a lot of hardware-based projects in the defense industry, and many of those employers were very resistant to change or innovation. At software development companies, creativity was encouraged and rewarded. Plus I could wear shorts to work, which in Florida is more a big deal than people realize for a sweaty guy like me.

At my previous employer before Atlassian, I acted mostly as the company’s Atlassian tools administrator rather than their Tech Writer. As such, I ended up throwing a Hail Mary and applying for a job with this company I admired, but on the other side of the world. It took me months to even get the courage to apply for the job with Atlassian, but they responded overwhelmingly positively. Not long after an offer I couldn’t refuse, my five-person family and I were off to Australia to work for Atlassian. I’d never been there, and never even really considered it as a tourist destination if I’m honest. But a progressive country in a beachy city that’s safe and clean seemed easy to get behind, and our family was ready for an adventure. That was 2015, and I’ve got to admit that it was not easy. It was certainly fun, but moving to Australia and away from our large support group of family and friends made us feel (or maybe just me?) isolated, and homesick.

In 2017 I changed teams, from Bitbucket Server to Bitbucket Cloud, and locations. Atlassian moved my family and I to the Bay Area after 2.9 years living abroad in Sydney.

To be clear, I went from living on government assistance to renting in the most expensive real estate markets in the world in a short amount of time, and much of the increases in my salary get swallowed up by the high cost of living or traveling to see family.

It wasn’t all bad, not by a long shot. Our family leaves a trail of forever friends whom we love and adore. And I’ve also grown as a professional in so many ways with Atlassian along the way.

The access barrier

TJ: Let’s transition into the Silicon Valley article a bit more. It’s challenging to break into tech comm in part due to the access barrier. Breaking into tech comm requires candidates to ramp up to a certain technical level while also developing a mastery of language. The ability to ramp up to the desired technical level requires access to computers and other equipment, the Internet, time, training, and encouragement.

Developing language and writing skills requires a lot of reading, study, feedback, mentoring, and other educational opportunities. For example, I have an MFA from Columbia. I also have a subscription to oreilly.com, and I only have to work one job. I’ve been to many conferences and had opportunities for training, local tech writing groups, and more. Developing technical proficiency and communication skills can be challenging if you don’t have these resources and time available. I haven’t even mentioned location requirements for jobs, which can be enormously costly in the Bay area and in other urban areas where tech comm jobs are most common. Basically, you have to be in the right location to be hirable, and the right location can be extremely expensive.

In the POCIT profile article, you mentioned that you were going to school full time, working full time, and raising a child as well while trying to transition into tech comm. Can you describe how you handled all of this? Do minority groups face more severe access barriers in terms of finding the time, training, access, and experience needed to become competitive candidates for tech writing jobs?

JP:

“Can you describe how you handled all of this?”

The secret sauce was my support group. In Orlando, both my parents and in-laws were within 5-10 min drive of us and could help watch the kids so I could go to school at times. And they were also always willing to take the kids for a night or two on the weekend so my wife and I could breathe/relax periodically. Honestly, this is the only acceptable answer. There are no super-human efficiency techniques I learned. I was an average student, at best, mostly because I was falling asleep all the time because I was perpetually exhausted. I was very fortunate to have peers and teachers that were understanding and sympathetic to my regular tardiness and general messiness. Many of my professors were friends of my mother, and I would also use her office to take naps and print out assignments right before class. That’s all to say I had a lot of help, and none of how I did it was graceful. But, finishing school will be one of my proudest accomplishments, because there was every indication I wouldn’t along the way, not least of which was that I was making quite good money by the time I was ready to graduate. Was almost as much as my professors! I nearly didn’t finish because I was missing a handful of credits that could only be taken during certain semesters. So I spent my last year of college taking 1-2 courses each semester to make up for missing core classes.

It would be disingenuous to say any of this was easy.

“Do minority groups face more severe access barriers in terms of finding the time, training, access, and experience needed to become competitive candidates for tech writing jobs?”

Yes. Full stop. Not only is it harder to take advantage of many of the free/low-cost opportunities at college because many of us don’t live on campus, or work, but many of the best opportunities for my career I only found out about because of my proximity to my mother and the English department. I turned my contractor jobs into course credit, and I took some independent studies, all while also attending any/all skills bootcamps offered by the English department. I got to go to several STC conferences on the university’s dime through our Future Technical Communicators (FTC) program, and my connections in FTC helped me get an important job later in my career.

UCF prepared me in a lot of ways for the workforce, but in so many ways I felt like I was just standing in the right place at the right time to take advantage of opportunities available to anyone. I just was always in the English department, so I heard about these things very early and could apply early.

But, I’m serious when I say I’ve actually had a professor wake me from a nap I was taking in my mother’s office to remind me class was starting. Those naps were live-saving, and he knew that. I once missed his class because I overslept, and he knew I was in the office. When he found out he told me he’d check my mom’s office before heading down to class next time. I’m telling you, the English department at UCF was like family to me, in that they all wanted me to be successful and were willing to help me in any way I asked.

Other minorities don’t have a fraction of that support, or if they do it’s not easy to utilize.

I get young parents asking me for advice on how to juggle all this and do it well, like I did … and it breaks my heart, because not everyone has what I had. And I’m genuinely not sure if I could have done it otherwise. I needed all that support, and probably more, to help me finish school.

The pipeline problem

TJ: The Silicon Valley article talks about the pipeline problem, where companies complain that not enough minorities are coming up through the pipeline from computer science programs, so there’s not enough minority candidates to hire. And yet, the pipeline preferred by many big tech companies in Silicon Valley is from elite colleges. Also, the DC area doesn’t appear to have the same problem in finding and hiring black candidates.

Regardless, tech comm doesn’t have the same feeder model as computer science. It’s more common for people to fall into tech comm from a variety of professions, not just through computer science programs. It’s also common for people to fall into tech comm at different stages in their career, transitioning from roles as engineers or scientists, for example.

So I’m not sure if the same arguments about the pipeline problem for tech apply to tech comm. Tech comm’s pipeline isn’t so straightforward. Maybe it’s more a case of needing a job to get experience, but also needing experience to get a job. But finding the time and opportunity to get experience can be challenging without an internship, without the right projects available, without mentors to provide feedback on your writing, without the time and space to build up this portfolio, without training, and so on.

Does tech comm have a pipeline for how new candidates are fed into the workforce? How are different groups more or less privileged in tapping into this pipeline? Does the lack of a straightforward entry path into the career pose additional barriers for entry, especially if you’re completely new to the tech comm domain?

JP: I am so glad you’re asking these questions, Tom. Because this is a topic I’m deeply passionate about, and have lots of familiarity with. I gave a presentation at one of Atlassian’s user summits called The “Pipeline Problem” and Myths About Workplace Diversity. In it I go over many of the same statistics and conclusions that the article you linked to does. Tech’s diversity problem is Tech’s problem, not the workforce. Yes, Black students aren’t earning as many CompSci degrees as their White counterparts, but it’s still at least 3 times the percentage as what’s currently in the high tech workforce. Nobody I know that’s Black was surprised by any of this, and in that presentation I go over lots of reasons this is prevalent in tech companies. Tech is aware of most of them, but their solutions vary greatly in scope and effectiveness. None of them are “doing” diversity very well, frankly, so long as they require people to be located in some of the most expensive real estate markets in the world.

Tech Writing falls along similar problems, with less clear sources of turmoil. As you mentioned, because there aren’t industry-wide standards for what we do, people from other career paths can transition without ever taking formal classes in Tech Comm/Tech Writing. I don’t even think that’s a problem. Along the same way, Tech Writing falls victim to similar patterns of bias in hiring, although (I suspect) with much better numbers in terms of women’s representation in the field. But Tech Writing isn’t immune to Tech’s problems, and the statistics you cited seemed to validate that hunch.

But I think Tech Writing is far better-positioned to make inroads into improving the balance of representation. I also think it’s just as important, if not more so, to have representation in non-technical roles like Writers or Designers. The kind of impact I expect to have at Atlassian might not be representative of the rest of the industry, but it should be. Tech Writers (and Designers) are on the frontlines of fighting bias within software applications. That’s not an understatement, and I find that even Black engineers can sometimes fall victim to coding bias into their programs by way of bias designs.

One need only look at the popular version control software Git to see evidence of how a Writer could have improved that product in many ways, like pushing back against using the term “master” as the default branch type, among other things. Or making Git use terminology that regular humans don’t need a cheat sheet to decipher.

Git is a great example of a barrier to entry for people outside of the tech industry. It’s something everyone entering the tech world needs to know, but is not even uniformly used within well-established engineers. It’s a daunting stew of confusing terminology, but is absolutely essential to know. And not just for engineers, either. I use Git to contribute to documentation all the time, and it’s only because I worked for a Git product that I have any real comfort using it.

But, you know, Tom, Git isn’t so hard. Most people can pick it up in a few online courses over a week without significant effort. The problem stems from knowing you need to know Git in the first place. Who tells you that? It’s this kind of seemingly trivial information that act as barriers to entry for otherwise exceptionally talented people to come work in Tech.

I’ve been doing a lot of interviews at Atlassian lately, and I can so clearly see the problems tech has even within my own company. Interview panels are only concerned with weeding out people instead of finding potential. They’re concerned with how polished someone is instead of seeing how difficult it would be to help them fill their gaps.

If someone doesn’t know Git, will you hire them to write dev docs? Why not? Because Git is teachable. But well-intending HR people use the lists of skills given to them from hiring managers as knives to trim the fat.

Networking hurdles

TJ: Networks are also a strong net that seems to keep others out. People who work together at one company might work together at other companies throughout their career, choosing to hire each other in a continual way. For example, I learned the other day that three of the colleagues I used to be with at a company in Utah are now together at a different company in Utah.

In-person networks such as the STC have membership fees that can be prohibitive. Even free groups like Write the Docs (WTD) pose challenges to members around access, transportation, and time. To attend a WTD meetup in the Bay area (before Covid19), I would have to ride Caltrain for an hour to get downtown to attend a 1 hour meeting, then ride 1.5 hrs back. It also costs about $20 for the round trip fare. It’s an event that takes up an entire evening, which would only be possible if one has available time and resources to attend these events. And yet, I’ve made a number of strong connections with others through these events that have been job- related.

How does a network exclude people who might not have those connections? How does one get the right connections to enter into meaningful networks to get jobs? Did connections help or hinder you in the job process?

JP: Your network will be the best predictive indicator of your potential for success in finding a tech job. That sucks, but there it is. Of course there are ways for people with merit few connections to land jobs, and they do, but Tech companies have the privilege of hundreds, maybe thousands, of applications to pick from. They aggressively screen people out before their applications ever meet the eyeballs of a human being. So it’s crucial to have a network of insiders to pull your application to the top of the stack, advocate for your interests, and keep people honest when things inevitably don’t go the way they should.

A great example is a recent referral for a position at Atlassian. This friend of mine is a career long tech industry leader. He held architectural and managerial jobs for some very reputable companies over the course of a very impressive 20+ year career which began as a full-stack engineer. I’ve lobbied this friend since I started at Atlassian to apply here, because he’s as interesting and compassionate as he is brilliant. I worked with him for two weeks to update and whittle down his executive-style resume, had it reviewed by two recruiters and the hiring manager for the role, only to have his application immediately rejected by one recruiter that was totally out of the loop.

I still don’t know the specifics of why that one recruiter didn’t feel my overqualified friend wasn’t even worth an interview, but this is actually typical of my referrals. I know the procedure by now. I went straight to the hiring manager after hearing my friend was rejected without even an interview, and asked if there was a problem. He’s on his 2nd or 3rd round of interviews now.

I’ve submitted over 30 direct and social referrals to Atlassian in the 5+ years I’ve been here. One has been hired, and she wasn’t even hired right away! I had to do the same thing for her, in going back after an initial rejection that felt far too fast. One conversation and updating her resume, she’s been here for 3 years is one of the highest performing people in her department. She’s viewed as not just a model Atlassian, but a difference maker in our company culture.

We almost didn’t hire her because someone overlooked her application almost entirely.

If not for my connections, which only gets folks another chance at consideration, not any special consideration, these more-than-well-qualified people would have been lost in the sea of qualified applicants.

Comparing Silicon Valley with other areas

TJ: You’ve lived in many parts of the US and even Australia, and you’ve worked in both the government sector and private sector. How does your experience in Silicon Valley compare with your experience in these other areas, especially in terms of finding and getting hired for jobs? Are there certain details that we take for granted in Silicon Valley (like access to tech or training), or things we don’t see because we’re in a bubble (like people who don’t have continuous and unlimited internet access)?

JP: I wanted to move to The Bay Area for the access, there’s no doubt. The cost of living was something I decided to tolerate for the opportunity to test a deep job market for my skillset. And I did. I interviewed with many of the biggest tech companies in the area, and Atlassian’s competitive offer and (mostly) supportive work environment is what keeps me here. I like working in tech, but I have a family to support, and on a single income in The Bay Area, even my generous salary I get from Atlassian isn’t enough to accumulate significant savings while living there.

Taking things for granted might be a stretch, because much of what’s offered in terms of training can be had online as well. It’s the long-running debate as to if it’s worth it to eat the cost of living in exchange for access to a lot more opportunities. The only thing that might be taken for granted is what California has to offer outside of tech. That’s hard to beat. I’m talking beaches, diversity, access to other parts of the country/world, and just stunning natural beauty in your backyard. Cali has a lot going for it, and Tech is just one of those things, So it’d be misplaced if someone only moved there to find a job. Move there because you love the beach, or like to eat vegan, or what to live in the most accepting place in the world of the LGTBQ community. Tech is like #5 on the list of interesting reasons to move to California.

There are tech companies doing cool stuff all over the planet. The Bay has more than anywhere else, yes. But if you don’t love it here the challenges can make you bitter.

The hiring process

TJ: During the hiring process, hiring managers and teams have to make decisions about candidates based on a short time period during the interviewing process (e.g., < 1 hour), yet hiring teams also have to be careful about implicit bias and other judgements. I’m always wary when “team fit” is introduced as a qualifier to endorse or reject a candidate, since team fit often seems to speak to the unconscious biases that we have. Other times, interviewers might rely on a gut feeling or a general sense about a person, or over-index on a small detail and convert it into a reason for rejection. How can hiring teams avoid implicit bias during hiring processes? Have you ever experienced this during your own job interviews, or if you were also interviewing others?

JP:

How can hiring teams avoid implicit bias during hiring processes?

Blind interviews. I’ve heard it pitched before, and I have no idea how practically it might work, but it’s very difficult to see any other serious solutions working. Take all the names and identifying information from an application, and then make a choice. I’m not an expert at how to combat bias, so I don’t really have any good answers on this that would be worth exploring in any kind of depth.

Have you ever experienced this during your own job interviews, or if you were also interviewing others?

Absolutely, and even quite recently within my own beloved Atlassian. Having awesome company values doesn’t make you immune to bias. For one job, the interviewer (who, at the time, I considered a friend) opened the interview informally, and the casually mentioned I probably wasn’t a good fit as I’m “more technical.” And the job was for a team that needed a lot of marketing-type copy. I was insulted. Marketing copy is stuff I’m really good at, and I am only ever viewed as “technical” because of projects I was assigned at Atlassian. I lean into that to make the most of what I’m given, but that she came with the assumption and so casually leaned on it before we even began the interview was more than insulting. It devalues my contribution and undercuts the opportunity.

Other times I was denied a job because the role was with a team based out of Sydney while I was based out of SF. I was well-qualified, and met all the criteria, but “the team” decided they needed someone onsite. Imagine my surprise when I met the new writer who eventually filled that role in the SF office, because he was based out of Mountain View. I guess “the team” decided it was fine to be remote, but only for someone entirely new to the company, not the guy working there for the past 4 years.

It got to the point where I felt I had to leave the product teams altogether, because I’d been on a product team for 5 years, with 5 different managers, and no promotion. A look back at my OKRs and personal goals is a depressing chain of unfunded projects and unsupported ideas that hurts my heart to even review. And despite being recognized as an expert in so many Atlassian things, I kept being put on teams that didn’t align with my personal goals or interests, despite my asking to change teams. That’s a recognized pattern for minorities, that we get the job no one else wants. It’s just one of an enormously long list of microaggressions we experience at work, all the time.

Anonymity as a problem more than benefit

TJ: The anonymity of the internet was once thought to be a great equalizer, but it turns out that anonymity seems only to encourage trolling, unrestrained hate speech, bullying, and other irresponsible and racist behavior. Are minorities working in tech exposed to a greater level of this negativity and harassment from people, or does this scenario only apply to forums like Reddit and Twitter, not really applicable to tech comm work?

JP: I’m not sure anonymity plays any more of a role to Tech Comm when compared to the general techie collective. If anything, being an anonymous author might help to avoid detracting from one’s authority in a piece of help and support documentation. For better or worse we all have bias, so there are times when it helps to just keep the task at hand the only focus. Tech comm authors have to be selfless in this regard, in that we don’t get to reap the notoriety gains from being a “published” author. Instead we take solace in knowing the job was done right, and the users get what they need. So anonymity might be a bit helpful in that regard.

Concluding thoughts

TJ: No doubt current events have cast this topic into the spotlight, even though systemic racism has been occurring for a long time. Do you have any other thoughts on this topic, particularly as it relates to tech comm, that you want to share?

JP: As allies, you all need to take a deep look in the mirror as yourself what you’re doing to improve Tech’s dire diversity numbers. And acquiring more minority employees is really only a part of the solution. Retention and promotion velocity are far better indicators of successfully balanced teams than raw diversity statistics alone.

It’s not enough to just hope minorities apply, you need to make space for minorities at your companies with progressive policies that will be uniquely advantageous to people from less prosperous socioeconomic backgrounds. Financial planning/tax advice, helping acquiring a home loan or paying down student loans, and flexibility in location to allow them to live in more affordable areas.

Finally, if you don’t start promoting Black and Brown people into management and leadership positions, you will never make significant inroads into making people feel like they belong. If I can’t see an example of myself in a leadership position somewhere, there’s no point in my sticking around to be their “first” minority anything. The Whiteness of the boardroom and managers’ table is telling, and the best of us aspire to leadership, so there needs to be precedence. Promote Black people, and stop waiting for the perfect storm of opportunity and “readiness” (which is bullshit anyway, no one is ready until they try).

About John Paz

John Paz is a senior content designer with more than 14 years of professional writing and editing experience. He currently works at Atlassian on the Field Operations team, which supports Atlassian’s largest enterprise customers. He has a BA in English from the University of Central Florida. Describing himself, John says, “I’m not the typical techie. I didn’t take a traditional path to working in tech, and I openly share my story to inspire others to find their place working in technology.” You can learn more about John at https://johnapaz.com and follow him on Twitter at @SrContentDesign. In October, John will be speaking at Button, a product content conference.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.