Experiments: What would happen if I exercised 2 hours a day?

Experiment: Two hours of exercise a day

My first life experiment has been to exercise for two hours a day. Why this goal? Two reasons. First, I needed to rehabilitate a recurring calf strain and prepare to play basketball again. Second, ever since I’d read an article in the New York Times that identified the “blah” feeling of the pandemic as languishing, I wanted to try something to dispel the blah.

Exercise for this experiment usually means low-impact walking, biking, kicking a soccer ball, or shooting baskets. (High intensity exercise for two hours each day would likely result in injury, not to mention it would be much harder to do.) I initially coupled this experiment with some weight-loss goals in an effort to get back in shape in anticipation of post-covid sports freedom, but my weight-loss efforts sort of petered out after a bit.

Regardless of lack of weight loss, I noticed that the increased daily exercise had a positive impact on my well-being. I felt more active, more alive, and more healthy. I noticed that if I didn’t get this exercise, my legs started to become restless. For example, at my kid’s soccer games, rather than sit down to watch, I preferred to walk around, even if it just meant just pacing back and forth along the sidelines.

My wife enjoys walking, especially hiking, so we’ve been going out more for these walks, as well as after-dinner walks around the neighborhood. My kids like to go on bike rides or forays to the park as well, which I’m ready to do (especially knowing that it will help get my exercise minutes in).

It’s no secret that exercise has a positive impact on mental health. In I Exercised Every Day for Two Weeks, and I Totally Underestimated How Happy It Would Make Me, the author says she exercised daily for two weeks straight and said the effect was “amazing” on her mental and emotional well-being. She writes:

Once I got through the initial soreness that’s to be expected from not working out for a year, my body felt lighter and looser than it had in a long time. I also noticed that I was falling asleep easier and waking up feeling more refreshed than usual. Mentally, I felt happier. Not happier in the sense that all of the world’s problems had gone away, but happier like a little dark cloud that had been hanging over my head moved slightly to the left.

The author references studies showing that regular exercise stimulates the production of seratonin, which helps regulate mood, sleep, social behavior, and other key aspects in your body. The author notes that most people stay motivated with their goals when they experience tangible results, and regular exercise certainly delivers on that, as you can clearly notice the difference it makes in your life.

In A Writer’s Reflections on Turning 80, Jane Brody says that getting regular exercise seems to increase importance after 50. For the first 50 years of your life, your body can rebound no matter what you do to it, but after that point, it’s up to you. She writes:

Assuming you don’t smoke, which was my husband’s undoing, Nature will usually take pretty good care of you for about half a century. Thereafter, it’s up to you.

Without regular exercise, you can expect to experience a loss of muscle strength and endurance, coordination and balance, flexibility and mobility, bone strength and cardiovascular and respiratory function. In other words, a sedentary lifestyle is a recipe for chronic disease and decline.

As I get older, I start to see the importance of regular exercise for all the reasons Brody explains. I’m only 45, but I can see the deleterious effects of a sedentary office life. As technical writers, we basically sit on our butts all day.

One downside to exercising more: I realized that I’ve been blogging less as a result, as more exercise requires more time (but it’s outdoor time). I very well could spend this time at home, sitting on the couch watching TV. In fact, sometimes at night, to get the required minutes in, I just walk around the block while watching a show on my phone. But supposedly, exercise stimulates cognitive function, so in the long run, I might be able to hold a train of thought longer.

After the 50 days, I decided to keep this goal/experiment. I didn’t want to return to the more sedentary lifestyle. I like the way my body feels with a more active lifestyle, even if it does carve a chunk of time from my day. However, I needed to modify the “two hour” rule of thumb with more nuance.

Refinements about points versus minutes

What’s wrong with the “two hour” exercise goal? First, two hours of exercise can differ dramatically in the intensity, calories burned, and body wear-and-tear depending on the activity. Walking slowly versus mountain biking versus wogging (walk+jogging) versus active soccer versus grocery shopping have different levels of physical impact. My simple rule of two hours didn’t distinguish the intensity of the exercise. It’s not fair to equate two hours of slow walking with two hours of intense uphill mountain biking. How can I keep the simplicity of two hours while also accounting for the differences in intensity?

One option could be to measure calories burned through fitness trackers (e.g., MapMyRide, Strava, Google Fit, Fitbit). I do use fitness trackers to attempt to measure my activity and see calories burned, but these trackers work best with only straightforward walking, jogging, or road cycling. If you’re shooting baskets, kicking a soccer ball in a field, or mountain biking in a hilly area, the trackers can be pretty inaccurate. For example, if I choose “Hike” in MapMyRide instead of “Walk,” MapMyRide says I burn about 800 calories instead of 300 for the same route. I also feel like shooting baskets for an hour should burn more calories than walking, but it’s hard to measure it.

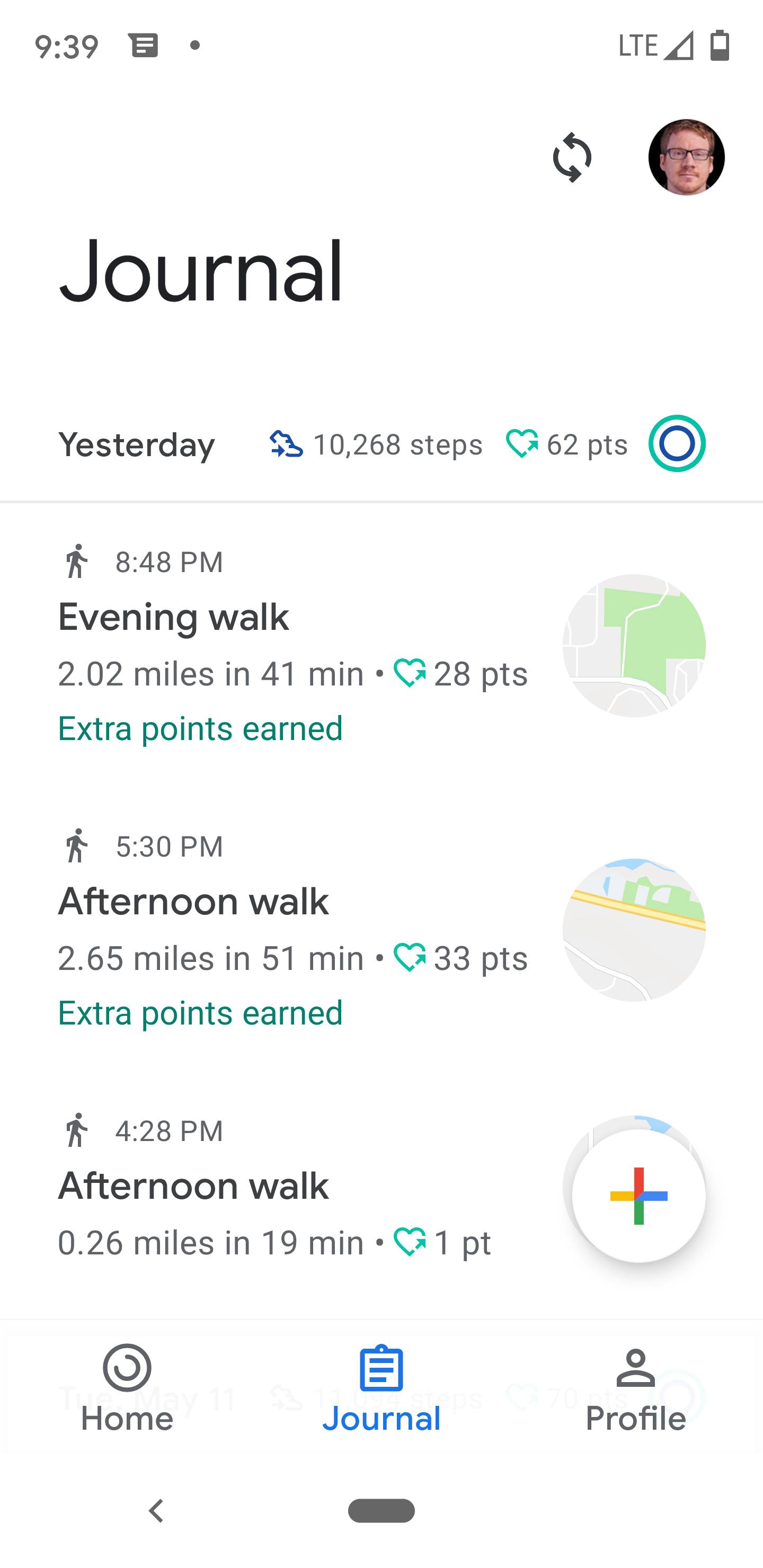

I’m still trying to figure out the best tracker. Google Fit’s estimations for walking and biking activities seem the most realistic, and it even counts my forays into the supermarket as a calorie-burning activity. Additionally, Google Fit also has another interesting metric: “heart points.” You earn heart points when you move more quickly; the points indicate that the exercise is more heart-healthy. For example:

Notice how that last “Afternoon walk” earned only 1 heart point? That’s because it wasn’t actually exercise — it was a stop at Safeway to pick up a few grocery items.

Google Fit describes heart points as follows:

Activities that get your heart pumping harder have tremendous health benefits for your heart and mind. You’ll earn one Heart Point for each minute of moderately intense activity like picking up the pace when walking your dog, and double points for more intense activities like running. It takes just 30-minutes of brisk walking five days a week to reach AHA’s recommended amount of physical activity shown to reduce the risk of heart disease, improve sleep, and increase overall mental wellbeing.

If using points instead of time, maybe 75 points (rather than 2 hours) seems like a good rule of thumb. That means if I decide to pick up the pace and move more quickly, I can finish my exercise in less than two hours. (In contrast, if the two hours is a static rule, there’s not much incentive to do more aggressive physical activity, and slow walks have fewer benefits than brisk walks or more active movement.)

Admittedly, two hours is practically four times what the American Health Association recommends, so keep that in mind. This is my own goal, not something scientifically backed, and there’s a good chance the extra exercise doesn’t add any additional benefits. However, recent news in exercise science has cast doubt on the previous recommendations of 30 minutes of exercise a day. Apparently, the 30-minutes-a day guidelines assumes that you aren’t sitting 11-12 hours a day but are actively filling in much of your day with light activity. If you’re sitting most of the day, 30 minutes isn’t enough to counteract the adverse of effects of over-sitting. An analyst from The Conversation writes,

As expected, we found that 30 minutes of daily exercise decreased the risk of early death by up to 80% for those who also spent less than seven hours a day sitting. But it didn’t have the same effect for people who spent between 11 and 12 hours a day sitting. In other words, it’s not as simple as checking off the exercise box on the to-do list. A healthy lifestyle requires more than 30 minutes of exercise if you spend a lot of time sitting.

For those who sat a lot, 30 minutes of daily exercise would only lower risk of early death by 30% if combined with four to five hours of light movement a day (such as shopping, cooking, or yard work) – spending less than 11 hours sitting total. We can think of this mixture of light activity, exercise and sitting as a “cocktail”. And when it comes to living an active lifestyle, there are different recipes you can choose to to get the same benefits. (Thirty minutes’ exercise won’t counteract sitting all day, but adding light movement can help – new research)

I’m not sure how much I sit each day, but it’s likely 11-12 hours, as I don’t think I’m standing and moving around for 5 hours. Anyway, I reference this study only to support the idea that two hours of exercise isn’t so far-fetched, and might be especially relevant for people in tech/office careers.

Coming back to the measurement issue, even though I like the idea of points, Google Fit (which assigns the points) doesn’t always capture every activity or capture them reliably. For example, a recent mountain biking ride doesn’t seem to have registered at all. Other times, Google Fit asks me if my activity involved riding a bike, as if it’s unsure how to interpret the motion.

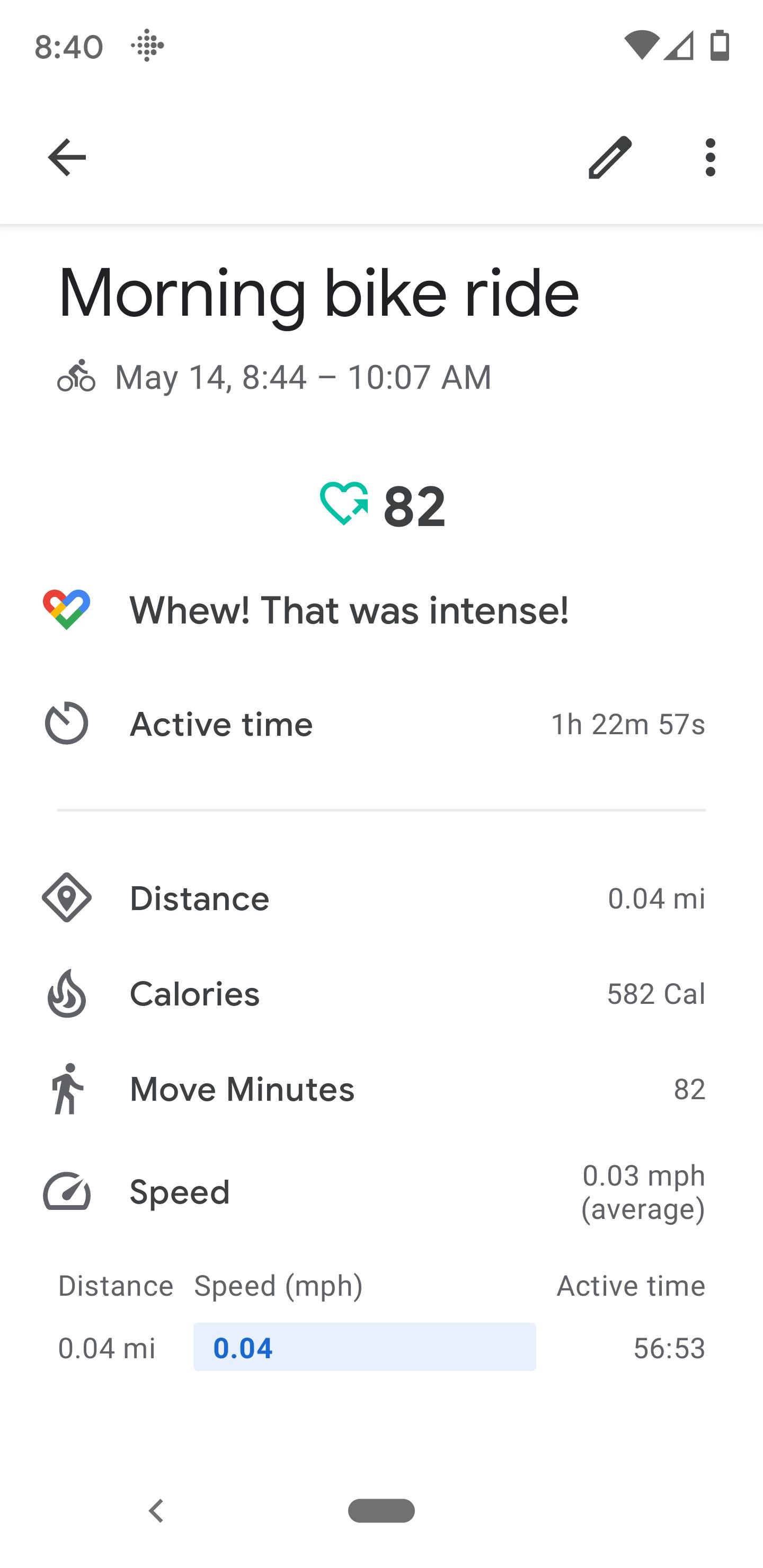

Other times, the analytics just seem wacky. For example, here’s a biking outing at Duthie, a mountain biking park, where my 82 move minutes resulted in burning 582 calories while going a distance of only .04 miles and racking up 82 points.

I’m not sure what happened there. .04 miles? .03 mph? For some reason, when Google Fit syncs with other apps like MapMyRide, the metrics often get distorted. The biking wasn’t intense. The Duthie bike park doesn’t offer challenging elevation climbs, just trails that loop and snake around with lots of dirt mounds, bridges, sloped corners, and other bike-parky things. Did I really deserve 82 points? However, this instance seems to be an anomoly to the norm.

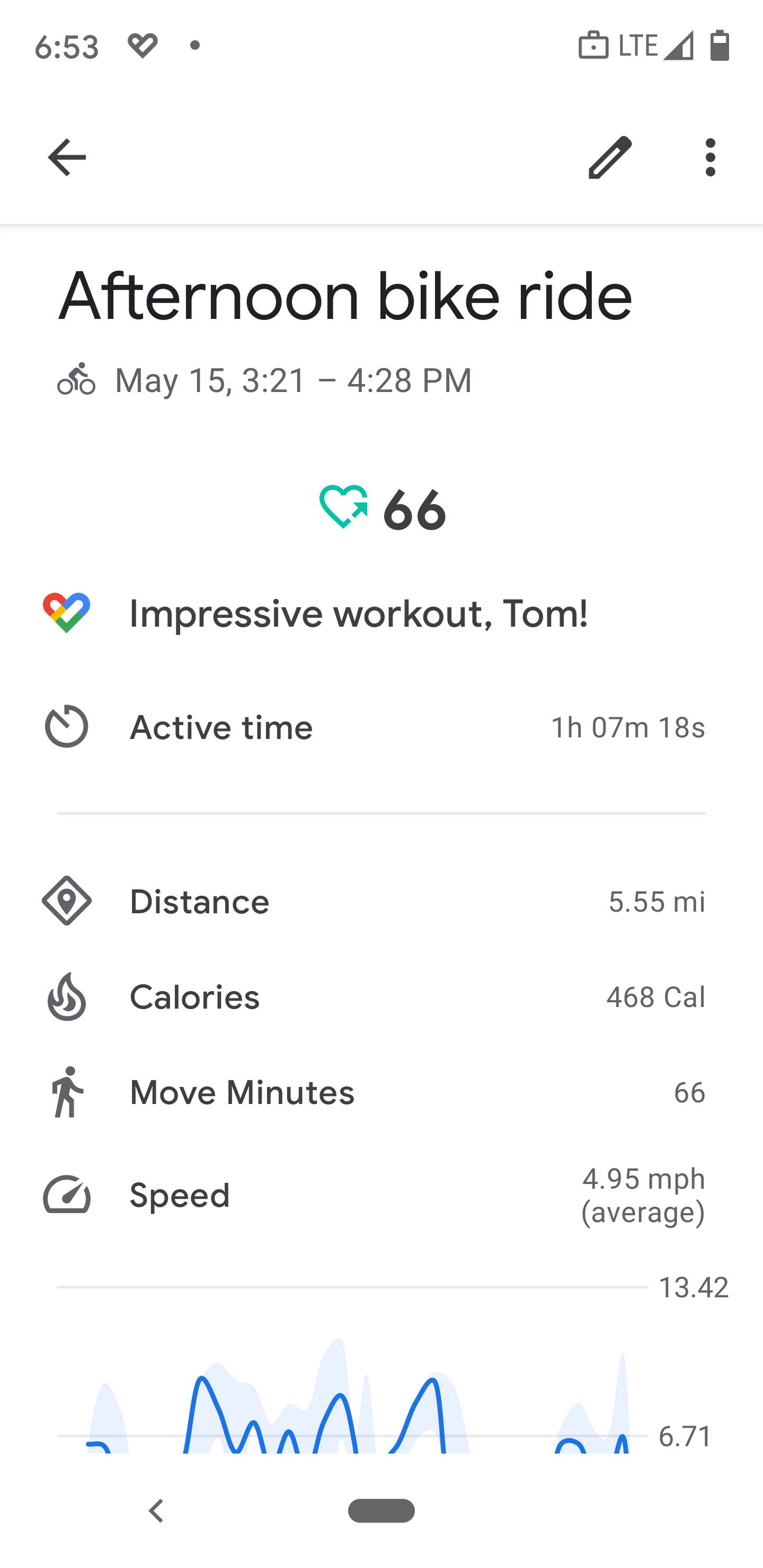

Here’s a normal Google Fit reading for another ride (within Spring Lake / Lake Desire) without the sync with another app:

This is much more expected and reflective of the ride. Overall, I like the idea of points, as it encourages more active exercise.

Note that the promotion of points instead of calories burned seems similar to the idea of “steps.” It seems like getting your 10,000 steps in for the day was all the rage (more than burning 1,000 calories or something). Whether steps or points, there’s definitely a trend against directly measuring calories burned.

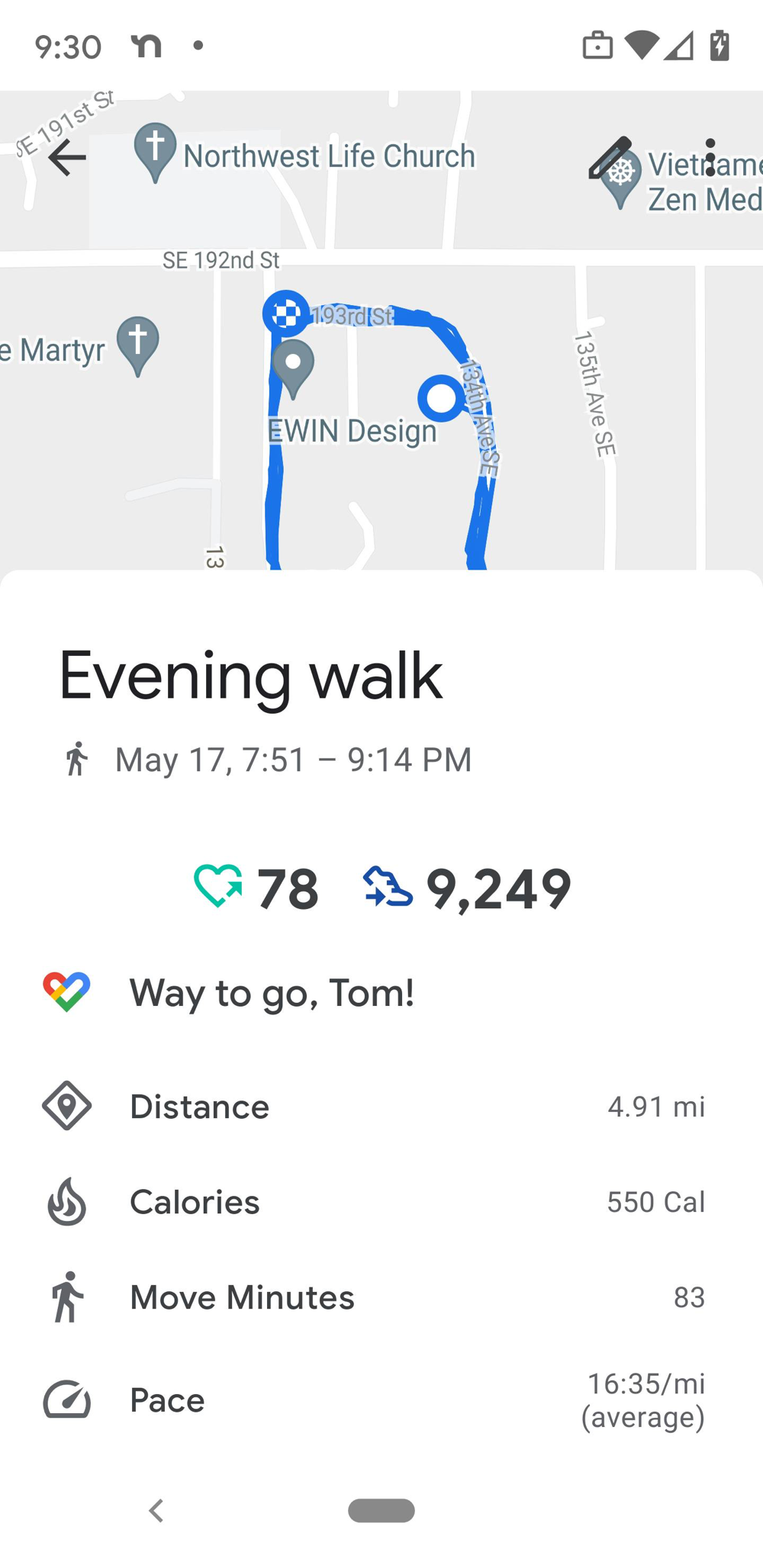

Whether you measure heart points, steps, or calories burned, it’s really challenging to get accurate results. Even among fitness trackers, there’s often a strong discrepency. Here’s a comparison for a 5 mile walk using both Google Fit:

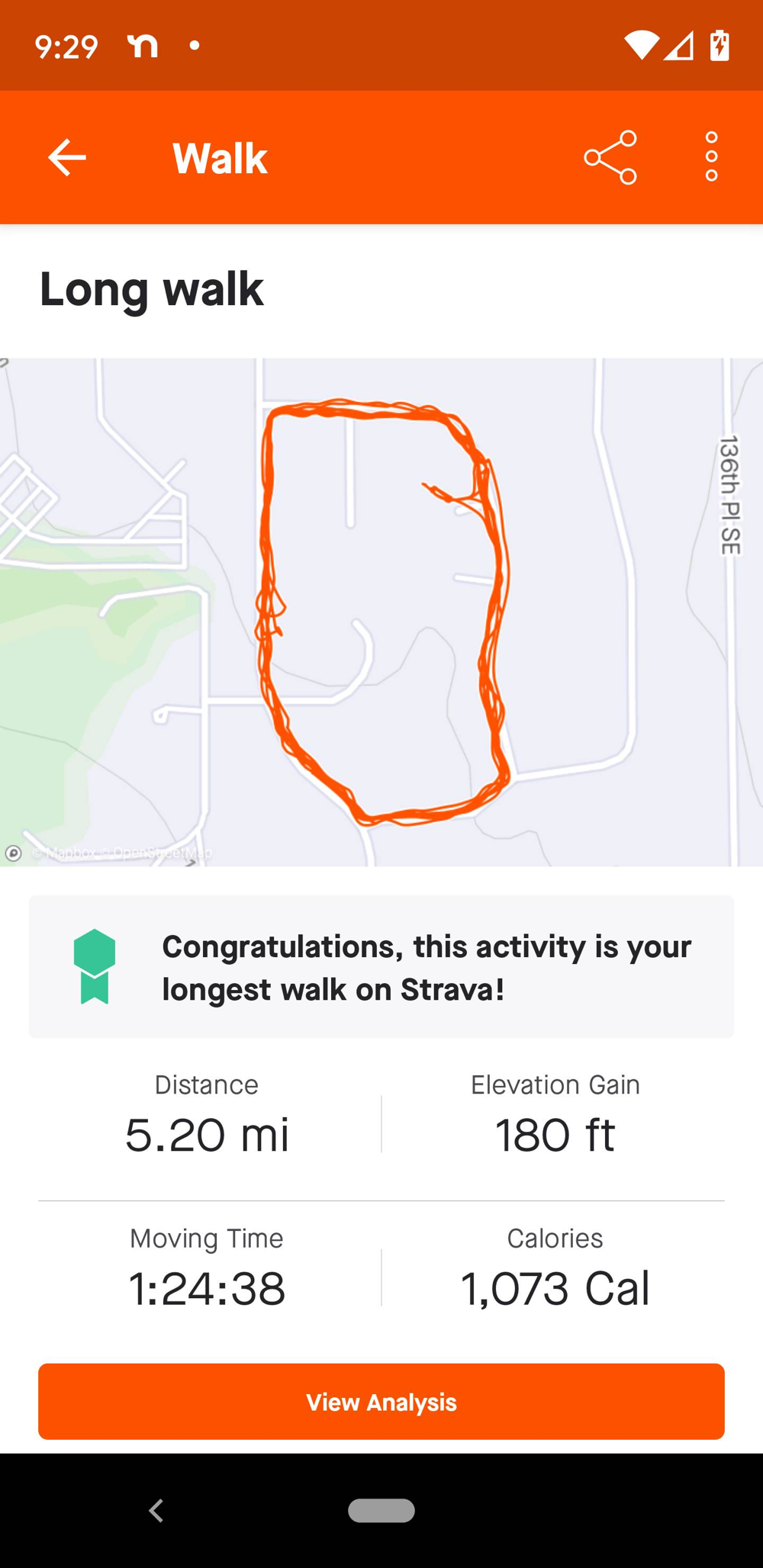

Now here’s Strava’s tracking of the same activity:

In both cases, the distances measured are about the same. So is the pace (not shown in the Strava screenshot). But for some reason, Strava thinks this activity burns twice as many calories as Google Fit. I’m not sure what’s going on with Strava here because other fitness calculators align much more with Google Fit’s estimation. If calories vary widely, it might make more sense to use another metric like points instead.

I’m getting lost in the details here. The important thing is exercise, not the exacting measurement of it. Here’s a picture of my mountain bike on the Lake Desire trail system:

And here’s wife and me atop Echo Peak, with Mount Ranier in the distance.

Exercise gets you outdoors. This also has tremendous benefit for tech workers who spend all day inside, staring at a flat screen.

Other notes

There’s much more I could write about this topic, such as the following:

- How a bike commute integrates time for exercise into the day that would easily meet the two-hours-a-day exercise goal

- How breaking exercise up into morning and evening segments makes it much more doable

- How your body adjusts to exercise levels, requiring you to either work out longer or more intensely to achieve the same benefits

- How a lot of people will be taking on weight loss goals coming out of the pandemic

- How the body just consumes more calories to compensate for those burned during exercise, and more

Overall, my main point was to experiment in some meaningful way and measure the impact on my life. Exercising for two hours a day seems to be a highly worthwhile lifestyle change that I definitely recommend. However, the best way to track exercise still seems to be inconclusive.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.