Autonomous Agile Teams and Enterprise Content Strategy: An Impossible Combination?

- Agile versus the enterprise

- Enterprise content strategy

- The case for and against independent documentation

- Strategies for unifying content

- Conclusion

Agile versus the enterprise

As our documentation teams at work have grown and fragmented, split and combined, often driven by the needs of agile teams spun up around new projects, it’s caused me to think about how agile fits in with enterprise content strategies. Agile teams tend to be independent, autonomous, smallish groups. They are single-threaded so they can be nimble and execute on a solution from end to end.

For example, companies might spin off a group of 20 people in various roles — engineers, testers, UX, project managers, and sometimes a technical writer — to build out a new solution for a long-shot project. Agile is a driving force that seems, at least in larger companies, to create startups within the enterprise. You need to move fast to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving tech landscape. Enterprises don’t move fast; startups do.

Agile engineering teams sensing extensive documentation needs tend to hire a dedicated technical writer specific to their team. These writers often arrive with only marginal obligations to adhere to wider enterprise concerns. If the writer has to plug into the same toolchain, taxonomy, style guide, re-usable content source, approval process, and publishing workflows as the enterprise, then you’ve slowed down the tech doc process and are at odds with the nimble and quick pace of agile development.

Enterprise content strategy

In contrast to the independent, autonomous efforts of agile teams, enterprise content strategy has much broader, more encompassing goals. An enterprise content strategist might ask how the documentation produced by a single team fits in within the larger enterprise context. This strategist would consider all the content touchpoints customers have across the enterprise through their product journey, from pre-sales touchpoints with marketing to touchpoints with solutions engineers, business development, post-sales touchpoints with tech docs, support, troubleshooting, and more. What is the customer experience from end to end? And how do you ensure consistency of terminology, style, and message across all of these enterprise lines?

Search is where enterprise content intersects – where customers see all content mixed together, often juxtaposed in often jarring ways. Enterprise content strategy by definition forces you to cross department and team boundaries to coordinate on a higher level. For example, enterprise content strategy might strive for a unified taxonomy for all enterprise content so that it can feed into a larger faceted search or content management system, where assets are described, shared, tracked, and re-used. Faceted search simply doesn’t work if all teams aren’t on board with the same terminology.

Is agile at odds with enterprise content strategy? And if so, are the benefits of enterprise content strategy strong enough to overpower the driving forces of agile? If the natural direction for tech writer dynamics in companies is small agile teams rather than coordinated cross-department collaborations and structures, is enterprise content strategy an uphill battle that’s simply running counter to trends in software development? Should we resist the move to unify content across the enterprise and instead be satisfied with the current product we’re documenting, without squaring and aligning it within the larger content landscape outside of our agile team’s concerns? These are tough questions.

The case for and against independent documentation

First, let’s consider the case for independent documentation, meaning docs produced by an agile team that aren’t integrated and aligned within any larger enterprise model. Any writer has to draw lines around their stewardship to survive, right? Take on too much, drawing the circles of ownership too large, and the work will crush you. You aren’t paid, most likely, to produce anything beyond the needs of your immediate business unit. The business lines of the organization define who you’re responsible to and what you’re responsible to produce. Sure, you could scour all enterprise documentation and champion a case across all doc groups (perhaps hundreds of technical writers in your organization) to fall behind a common style guide and approach in docs, but why? You’re paid to write documentation for a product from a particular business unit. Everything else is extracurricular. The additional effort to unify content across the enterprise will exhaust bandwidth you don’t have, maybe even require weekends and overtime work.

Focusing your vision only on your agile team’s needs is a valid position to take, but the content produced will likely be poor quality. Content produced separately by many different teams written in different styles, published by different tools and systems, without any larger awareness often results in a fragmented and disjointed content landscape.

Even setting aside documentation concerns, engineers who build in enterprise isolation face similar problems. If engineers build separate systems that don’t integrate, the user experience also ends up being disjointed and frustrating. Users might find that one SDK doesn’t integrate with another, or that one tool is built on a technology that is incompatible with another. At a previous company I worked at, customers were fed up with disparate systems that didn’t integrate with each other. When two major customers (who brought in millions) threatened not to renew, it caused shockwaves across the company. Business leaders halted the development of all new products as software teams undertook efforts to make the existing software work as a harmonizing suite of applications.

A hodgepodge of technology is understandable in mergers and acquisitions, but few users will be patient with the idea that the single company they interact with is actually made up of dozens of small, independent internal companies that don’t seem to know what each other is working on or building, since none of the products work together. As a worse case, in massive companies, totally isolated teams might even be working on different solutions for the same problem, unaware of each other’s existence.

Good documentation can’t be written with blinders on. I wrote about the need to make information harmonize in the larger landscape in Principle 3: Ensure information harmony in the larger landscape from my series on Simplifying Complexity. The basic principle is this:

Before adding new topics to an information landscape, look to see how the new information will fit in with the existing information — across all information forms, from docs to blogs, forums, white papers, and more. Synthesizing information to harmonize with the larger information landscape requires wide reading and analysis but is essential for the user experience, since users often bounce from one information source to another as they consume information._

Without question, it’s much harder to understand the larger landscape in which you’re writing and to assess how the content (the terms, styles, semantics, etc.) you’re using fits into other content for which you likely do not own or have stewardship over. It’s easier to write a standalone article and push it out, like a blog post.

Strategies for unifying content

The traditional strategy for allowing autonomous teams to harmonize within the larger content landscape is to create style, brand, and design guides that everyone in the enterprise aligns with. UX and marketing teams are excellent at producing these guides — clearly explaining color palettes, voice, logos, and usage.

Style guides for tech docs are similarly helpful, but content by nature is messy. Rather than merely clashing in style, written content has the added problem of not making sense with other written content. Content on any doc site might all read with the same general tone and follow similar structures (due to convention with industry standards), but in many places the content might be muddled and confusing. The content might use different terms to refer to the same process or have functionality that overlaps, or it might present solutions without adding context of similar or contrasting solutions within the same space. Those intermixed semantics are what degrade the user experience, not necessarily differences in title case versus sentence case heading styles.

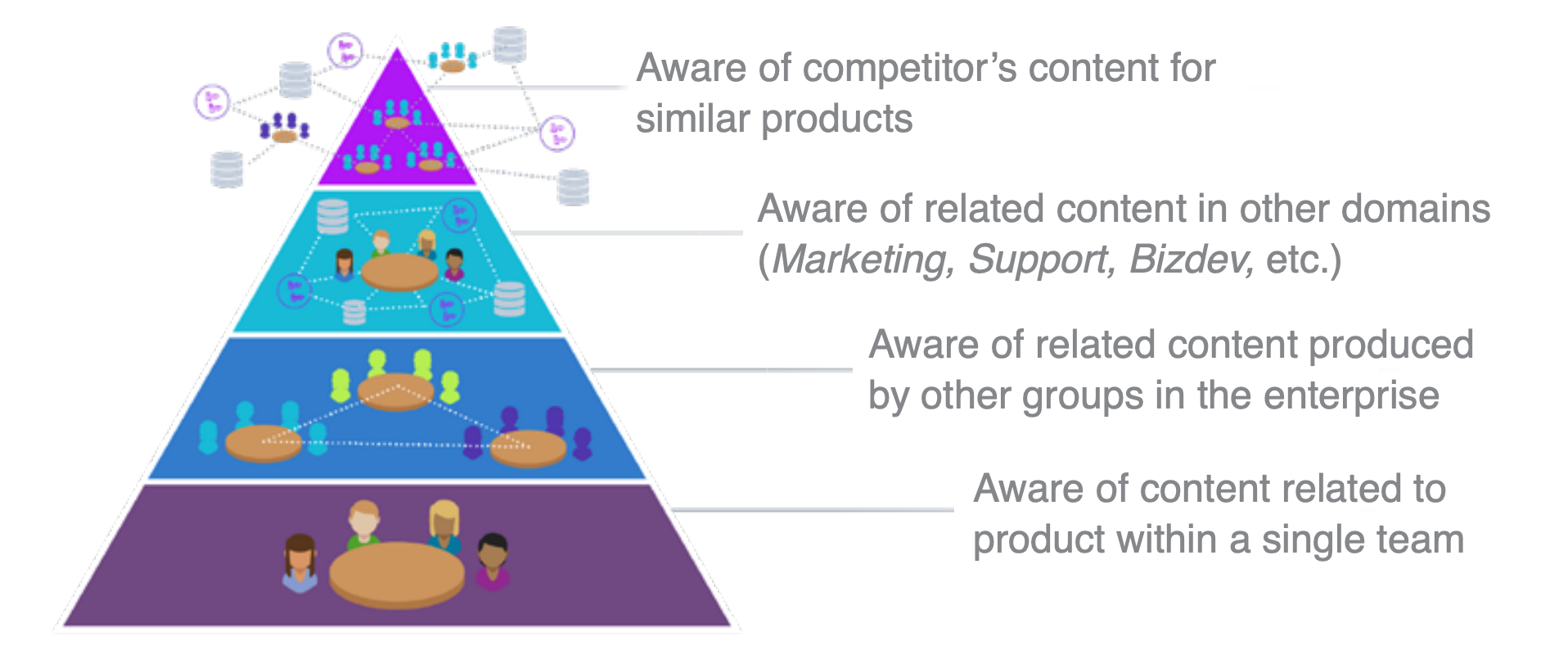

Independent documentation that doesn’t consider anything beyond itself might be acceptable, just as a C or B- might be a passing grade on a test. To increase the quality of documentation, writers have to increase their sense of awareness. The following graphic shows these degrees of awareness:

The first level of awareness is to master your own product. Understanding your product as a SME is practically required to write detailed documentation in the first place.

The next level is to be aware of documentation that other technical writers in other groups are working on. This is more applicable in larger companies with more than just a few tech writers. Good writers expand their horizons to understand docs they don’t necessarily own but which have some influence or relationship with their docs.

The next level is to be cognizant of content outside the documentation domain — content on blogs, white papers, ebooks, business development slide decks, and other collateral produced by other groups outside of documentation. Groups like field engineering, business development, support, and so on are, in fact, producing content. Technical writers often aren’t aware of this content.

Stretching awareness even further, a good writer should also be aware of the competitor’s landscape. I wrote about this in “My documentation takeaways from the Boeing disaster – two essential doc questions to ask for any project.” In that post, I argued that good documentation should address the question, “How does this product differ from other products?” This question is rarely addressed in documentation since many companies do not call out competitors or compare their products with competitors.

This is one area where practitioners can learn from academic genre conventions. As a required section in academic articles, before diving into the details of one’s argument, nearly every academic article presents the context of previous research that has been done on the topic previously. Academics don’t just start writing without awareness of what has already been written on the topic. They start by surveying the landscape, summarizing what other research has been done, and then moving forward with their current argument. In documentation, this kind of landscape survey might involve mentioning how the product fits in the enterprise and competitive landscape of similar technologies.

Conclusion

Most writers won’t expand their horizons to consume more than their immediate product documentation requires. No one will force you to read documentation written by other departments or docs written by competitors. So should you even bother? Surely this expanded analysis isn’t scoped into your project plan or expectations, right? Where do you find the time or bandwidth to do it?

I’m not sure. Those who write our paychecks often won’t factor in time for this, especially given the time you already need to ramp up on the product’s technology itself (which is not insignificant in the developer documentation space).

Although I want to champion enterprise content strategy, if the web has shown us the future, the future is probably independent publishing from disparate groups. It works out all right for the most part on the Internet, though enterprises might have another standard. For example, you won’t see articles in WebMD addressing articles from Yahoo Health covering the same topic. When you search for content, you get a lot of different hits on the same topic, with different approaches and styles and perspectives from different authors at different times on different websites. Content on the Internet is redundant, outdated, disjointed, written in different styles for different purposes, audiences, business contexts, and more. But it works out all right – users find what they need, ignoring content that doesn’t quite match their search.

In the tension between agile and the enterprise, most likely one finds a middle ground here — finding some awareness of other content but not extensive awareness. In general, good writers will read beyond their agile team’s boundaries to provide better semantic context and fit with their content, but none of us has time to read endlessly and widely before the doc is due and another project takes the stage.

Whatever your position, if you want to write more informed documentation, try to climb up the pyramid of awareness. Start with awareness of content related to your product, and then as time permits, expand to learn about similar content across the company, then look at the same content in other business groups, and finally expand your analysis of competitor documentation for similar products. Most tech writers do the base layer and maybe the second, but few climb up higher.

You can see more comments on this post on Linkedin.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.