My documentation takeaways from the Boeing disaster -- two essential doc questions to ask for any project

- The Boeing disaster’s relevance to tech comm

- How does this product differ from other products?

- What does the customer need to know?

- Conclusion

- Your reactions and input

The Boeing disaster’s relevance to tech comm

I’ve been following the recent Boeing airline disaster in part because of its relevance to the world of tech comm. A recent article noted that “one captain call[ed] the flight manual ‘inadequate and almost criminally insufficient’” presumably for not “fully disclosing information about how its systems were different from other planes” (Several Boeing 737 Max 8 pilots in U.S. complained about suspected safety flaw).

For background on the story, listen to this New York Times Daily podcast, Two Crashes, a Single Jet: The Story of Boeing’s 737 Max. In a nutshell, to achieve more fuel efficiency, the 737 Max used larger engines and placed them further up on the plane, which changed the way the planes handled. To automatically compensate for changes in pitch, engineers added a Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) to make automatic adjustments by reading from sensors. This MCAS software automatically pushed the nose down to prevent stalling (or something). But many say the sensors were faulty, so the MCAS was pitching the nose of the plane down, and pilots countered by pulling up, and after awhile the planes crashed (analysts are still investigating exactly why).

First, I want to say that I’m glad people’s lives don’t depend on the documentation I write. I can only imagine how much anguish this team must feel around these disasters. Also, documentation for airlines is a highly regulated industry that I know little about. These flight manuals can be hundreds of pages long (here’s an example of a flight manual) and require approval from many writers, engineers, pilots, administrators, analysts, and FAA regulators before release.

Despite my lack of knowledge in this area, when I read about these reports, the following takeaway questions come to mind. They are applicable to pretty much every documentation project.

- How does this product differ from other products?

- What does the customer need to know?

These are tough questions. I’ll tackle both questions in the following sections.

How does this product differ from other products?

This question is actually rarely addressed in documentation, since many companies do not call out competitors or compare their products with competitors. For example, even though my audience for Amazon Appstore documentation are users who presumably have apps that they’re also submitting to the Google Play store, I rarely call out differences between Amazon Appstore and Google Play. There are two reasons for not doing this.

First, callouts like this require me to be familiar with other products and systems. It takes a lot of knowledge and awareness to write about how, say, developing an app feature for Amazon differs from developing an app feature for Google Play or developing a feature for Apple’s Appstore. You barely have enough time to ramp up on your own products, let alone provide more in-depth cross-industry comparisons.

Also, comparisons inevitably invite judgment, and in my experience, product managers run from this like a disease. As soon as you start explaining how your product differs from competitor products, you’ll raise questions in the user’s mind about pros and cons, advantages and disadvantages, and such. It seems so much safer and easier to just write about your own product, and let users bring their own background and experiences with other products to the text in order to draw their own comparisons. Legal departments also do not like technical writers writing about competitors in documentation.

With the case of the Boeing plane, I’m pretty sure the Boeing manuals don’t include any comparisons with the equivalent Airbus model that prompted Boeing to create the more fuel-efficient 737 Max in the first place. I mean, most guides don’t start out saying, “If you’ve flown the Airbus, then you’ll be somewhat at home in the 737 Max, as the two are similar in many respects. But whereas the Airbus handles like this …, the 737 Max has this little software program to help automatically adjust for pitch and such …” And yet, I have to wonder whether this kind of comparison might be more warranted (in retrospect).

Anyway, previously I wrote about the need to read competitor documentation to make sure your terms align with industry-standard terms. See the section Does your documentation use industry standard terms correctly? Beyond using industry-standard terms, though, comparisons with competitor products and features require a lot more work and add significantly to the scope of documentation efforts.

Putting aside comparisons to other products, one might rightly criticize Boeing for not doing more comparisons within their own product line. Even so, comparing products within your own company might also be challenging. One of my doc pages includes specifications for Fire TV devices. On the page, I list specs for 13 different devices, with brief summaries at the top where I try to compare the devices at a high level.

It’s actually hard to get buy-in for some high-level comparisons between devices. I can’t really say, “This device is less expensive and assumes you don’t need HD, whereas this model gives you a more seamless experience with antenna inputs as well. Or … This device has a high-performance chip, whereas this other device will be sluggish if you do anything more than stream media….” Instead, most product managers would prefer that I simply list the specs and let users draw their own comparisons. And yet, a more comparative assessment is probably what users want and prefer.

What does the customer need to know?

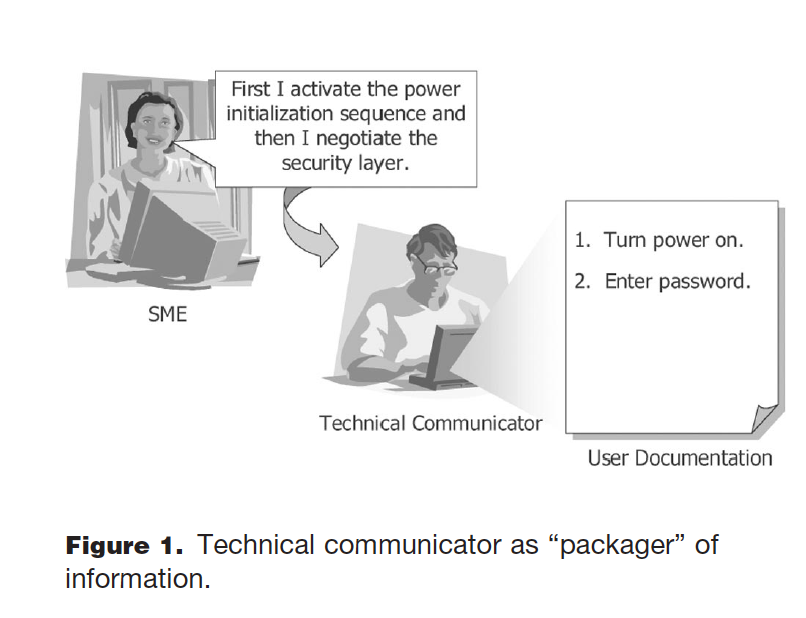

Let’s look briefly at the second question: What does the customer need to know? This question is one that technical writers constantly evaluate. It’s the question we regularly ask as we try to reduce and simplify content. I wrote about this in Reduce information bloat (a section within a larger essay called “Principle 4: Reduce and distill vast information down to its essence”). In that essay, I cite an article from Mike Hughes who depicts the technical writer’s job like this:

As technical writers, we frequently ask, does the user need to know this information to perform his or her task? Is this information just unnecessary background knowledge from engineers? In my essay, I explain:

When some engineers write, they have a tendency to over-explain the details of how something works rather than providing the minimal amount of information the user needs to accomplish their task. For example, an engineer might explain the intricacies of architecture and design even though the user just wants to know which button to press. Reducing the information that falls outside of the user’s task needs is usually the first step a tech writer takes to simplify content.

Reducing information bloat is actually a byproduct of minimalism, a concept put forward introduced by John Carroll. (Principle 4: Reduce and distill vast information down to its essence)

In the Boeing situation, apparently the training omitted explanations about the MCAS software, which applied the automatic pitch correction. This omission is what frustrated pilots. In this case, it was clearly something they wanted to know about.

The situations I encounter related to information inclusion/exclusion are situations where product managers (PMs) want to omit any documentation around potentially negative aspects of the product. Most PMs prohibit tech writers from explaining anything in the documentation that might amplify “negative sentiment,” as one PM called it.

For example, I once documented an app template that had some restrictions around monetization, package names, and advertising. When I called these out more prominently in the docs, the PM feared that I might be raising awareness about negatives that the user didn’t already have questions about, so we toned these down and put them into a less visible FAQ. (I wrote about this in Transparency in documentation: dealing with limits about what you can and cannot say.)

Other times, PMs will simply change the “spin” on some information. For example, one feature I was documenting lacked more informative analytics about system performance. I called this out and said users would need to use third-party analytics tools to gather this information. In this case, the PM didn’t say to omit the info, but he spun it more positively, noting that additional info could be available through third-party analytics tools.

In general, one reason I like working in the documentation domain is because there’s less scrutiny about the content, so more frequently than not I have free reign to speak plainly about a product’s limitations. Usually, engineers are 100% on-board with documentation that transparently lays bare all limitations, assumptions, and other criteria about a system. They don’t want to be blamed when the product doesn’t do what customers want.

In the case of the Boeing training for MCAS, I’m not sure if this is a potential negative that PMs didn’t want to expose, or if it’s really just a background system that, if working properly, would be entirely invisible to pilots and therefore unnecessary for them to learn about. My guess is that it probably would be seen negatively. How else would you spin this kind of statement — “The handling of this plane is going to be a bit different (due to the engine placement), so we have this little software that automatically fixes your maneuvering. If it goes haywire, just use the kill switch.”

I can imagine that if I bought a bicycle that had a maneuvering software like this — some mechanism that might detect if my angle is too far left or right and would automatically rebalance the bike to try to move me upright — I’d certainly want to know about this rather than be surprised by my bike’s sudden balance-correction kicking in.

In an era of self-driving cars, this topic will become more of an issue. With electric vehicles that have extensive software under the hood (e.g., Tesla), with many self-driving features built-in, drivers will need to be aware of what software might be suddenly adjusting their controls.

Conclusion

Again, I want to repeat that I know almost nothing about documentation related to airlines and FAA regulations and such. I’m only commenting on takeaways that I perceive to be relevant to the type of documentation I write.

Also, it’s worth noting that the training for these pilots doesn’t just include documentation but usually involves multi-million dollar flight simulators that pilots would need to train a certain number of hours with. It’s not as if pilots are turning pages in software manuals before firing up a billion-dollar plane. (Though apparently, the training for the 737 Max included just 58 minutes on an iPad, according to Trevor Noah on the Daily Show.)

Still, I think the questions I raised here are semi-applicable to most documentation projects. They are by no means easy questions to address.

Your reactions and input

Would you like to share how you align with some of the topics I’ve discussed? Here’s a short survey to collect your input. You can view the ongoing results here.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.