Changing the AI narrative from liberation to acceleration

- Introduction

- The AI narrative

- Hard limits to velocity

- Increasing speed means risking more error

- A world sped up

- A new AI narrative

Introduction

There’s a pretty depressing post on the techwriting subreddit right now: AWS tech writers majorly impacted by today’s layoffs … with nearly 968 likes and 94 comments to date. In the post, one of the former AWS tech writers writes:

… it doesn’t matter that AI can’t do everything we do. It doesn’t matter that the quality is noticeably worse than our writing. It doesn’t matter that it doesn’t know all the overhead and confusing internal systems that we use to get our docs out the door. Corporate leadership doesn’t care about any of those things. They will give you AI tools, train “you” to use them (it’s really the other way around - you’re training it), tell you that it’ll make your life easier, and still let you go in the end.

It’s a sobering thread that has many in the industry upset, and understandably so. However, a recent New York Times article, “Mass Layoffs Are Scary, but Probably Not a Sign of the A.I. Apocalypse,” suggests a different reason for the layoffs. The author, Noam Scheiber, argues that companies might be cutting staff not to replace them with AI, but to free up capital for massive investments in AI infrastructure. Scheiber quotes an analyst who says, “…the companies appear to be making the cuts partly to hold their overall profit margins steady while they spend tens of billions of dollars on A.I. infrastructure like data center.” This perspective adds a layer of nuance to the situation, suggesting the layoffs might be more about financial strategy to fund AI growth rather than direct human replacement.

Even if the layoffs are primarily about reallocating funds, the move still reflects a dangerous confidence in AI’s ability to compensate for a smaller workforce. This confidence is rooted in the common “liberation” narrative about AI, which I believe is misleading. In this post, I argue that laying off employees in the age of AI is a short-sighted strategy, regardless of the immediate financial motives.

Laying off employees in response to AI could be a short-sighted strategy based on a static pace fallacy, which is the assumption that the amount of work is fixed. In reality, AI accelerates the entire competitive landscape, increasing the overall pace of work. Moreover, AI shifts the bottleneck from content generation to human validation. Companies will need their human workers, augmented by AI, to manage this new, higher-volume validation bottleneck and keep from falling behind.

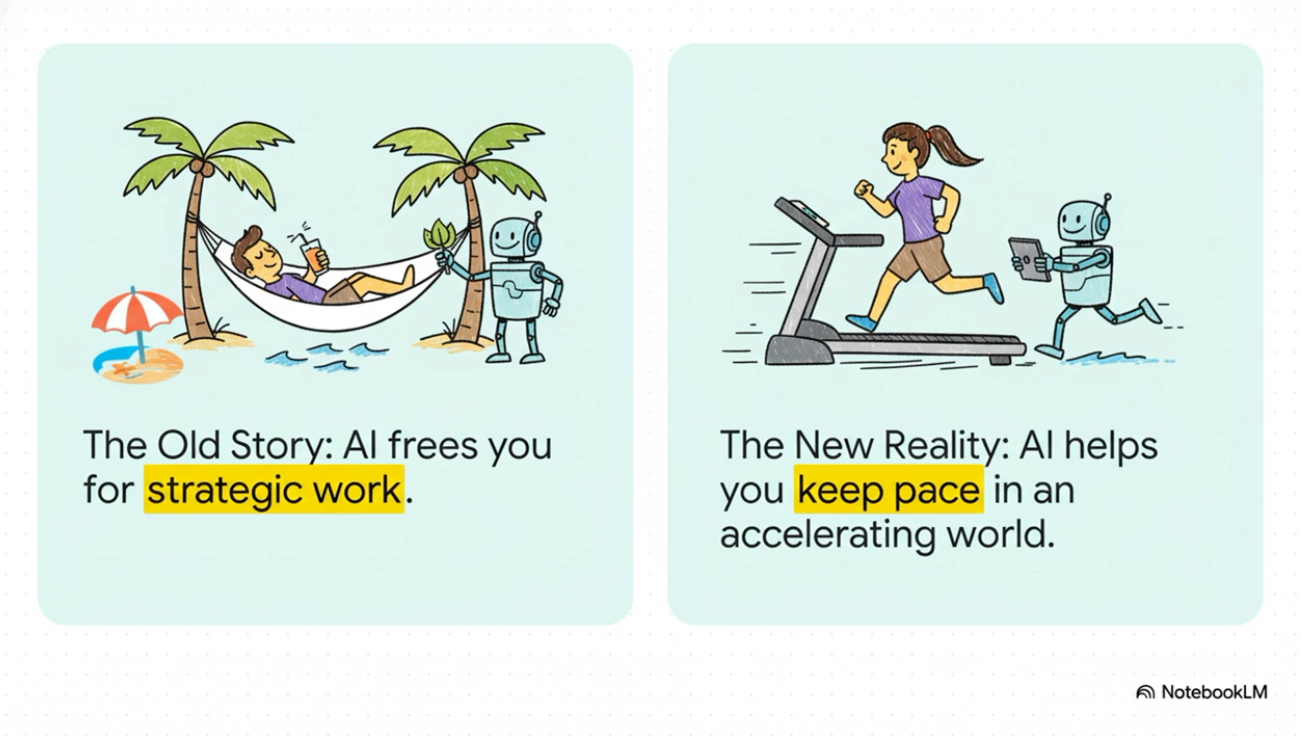

For a short video (7 min.) of this post, see this NotebookLM video. The images in this post are from the NotebookLM slides.

The AI narrative

The AI narrative, if there is a general one, goes something like this:

AI is going to make you so productive, you can do 3x as much and free up time for more strategic, important tasks that AI can’t do.

I frequently hear professionals noting how AI allowed them to do tasks that might normally take a long afternoon of tedious work.

CEOs probably hear this and think AI will allow us to do the same with one third the number of employees. As a result, you’ve seen the flat hiring and the increased pace at which tech writers are working. However, this thinking (reducing employees because AI can do their work) commits the static pace fallacy—the assumption that the total volume of work and competitive expectations are fixed, rather than dynamic and accelerating.

Here’s what most people overlook in the AI liberation narrative: If AI speeds up your productivity, it speeds up the productivity of everyone around you too, including every company in your domain and abroad. So those other companies will also deliver faster, with higher quality, and more prolifically if they’re also using AI.

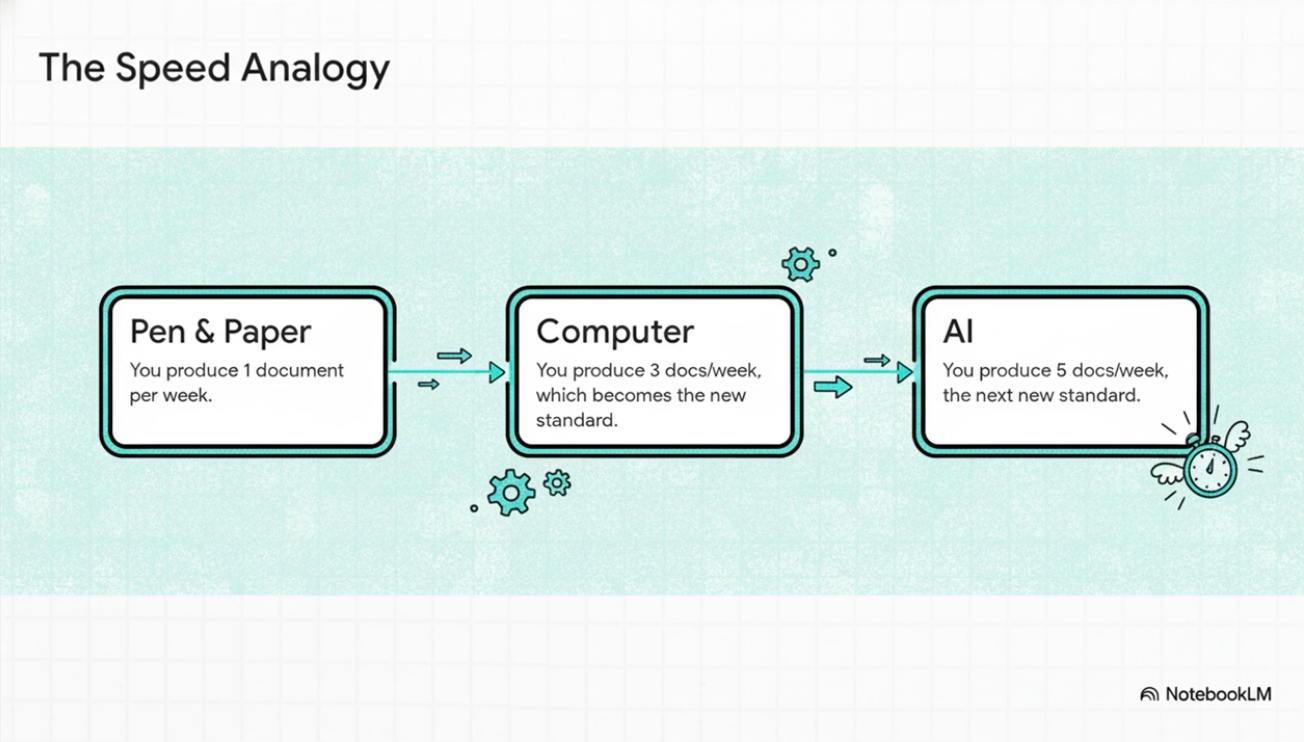

Here’s an analogy for this argument. Consider the computer’s effect on writing. Let’s say you, a tech writer working in 1990, get a computer, learn to type, and realize that you can write a lot faster and easier using this tool. It even doubles your productivity versus writing by longhand with a pen. It’s amazing. For the first few months, your productivity soars because not many other writers have computers, and it’s become your secret weapon. Whereas with pen and paper you might have written 1 document a week, with a computer you now produce 3 documents a week.

However, within the year all the other writers have computers too and are using them to match the same increased levels of productivity. Pretty soon everyone else is also producing 3 documents a week.

Now AI comes along and wow, it’s another leap in speeding up technical documentation. As an early adopter you figure out the tools, the prompting techniques, and how to integrate AI into your workflows. You’re no longer producing 3 documents a week—you’re creating 5 documents a week. For the first few months, you’re ahead of everyone else because some writers are slow to learn new tools and processes.

But before long, the other writers also figure out AI, get access to the complex reasoning models, and learn how to integrate them into their workflows. Everyone is now generating 5 documents a week.

Now consider that AI is speeding up the roles of everyone around you too—developers, product managers, lawyers, customer support, partner engineers. Everyone has ratcheted up their productivity a couple of notches. Because speed is relative, any early advantage you might have had in using AI to produce more documentation is negated as the entire system accelerates. The number of requests simply increases to fill the new capacity.

The net result is that although your productivity is 5x as much, your workload is 5x greater too. Whereas before you supported 1 software team pushing out a major release quarterly, now you support 3 software teams pushing out major releases monthly.

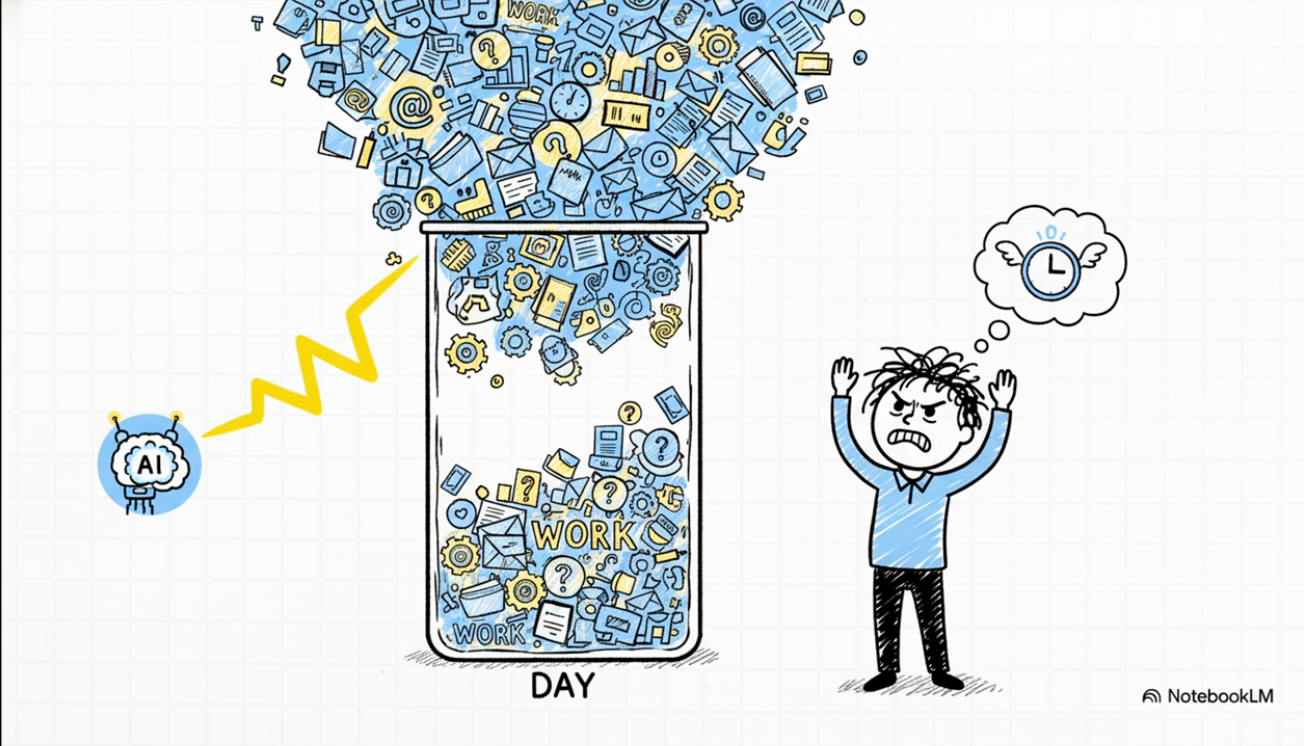

Now come back to this idea that AI tools will liberate you from tedious work and free you up to focus on more impactful, strategic work. That “free time” never unfolds like you think it does because the workload just increases all around. I might not be spending 3 hours formatting entries in an HTML table and troubleshooting rendering errors. But I’m also not seeing my bug queue slim down and my bandwidth open up to tackle more strategic issues. I simply have 3x as many doc tickets coming in.

The net result of AI is to speed everything up. This increased speed is that breathless feeling almost everyone has experienced lately. Hardly a week goes by that you’re not inundated with announcements about new AI tools, integrations, techniques, events, training, and more. This has led to AI fatigue. It’s exhausting.

One of the most prominent proponents of the idea of acceleration is Ray Kurzweil and his idea of the Law of Accelerating Returns (LOAR), as he argues in The Singularity Is Nearer. His argument is that technology’s pace increases, in part, because it’s generating a feedback loop of tools that allow for increased development. AI gives rise to more builder tools: it’s a tool that builds other tools, which allows you to create more and more products easier and faster. Think about the invention of the engine, or electricity, or the internet—these innovations enable new capabilities/inventions across domains.

Kurzweil says the Internet, an invention with feedback loops to expand more technology and new businesses, doubled labor productivity for a decade. If the Internet gave rise to new industries, professions, companies, economies, etc., imagine what AI will give rise to. Will AI double or quadruple labor productivity? If so, won’t that accelerate the pace of innovation in the corporate landscape?

The time between major inventions is undeniably shrinking. Simply go to Timeline of historic inventions and scroll down; notice the timelines shrinking between major inventions. For more recent inventions, see List of emerging technologies. Kevin Kelly also makes the acceleration argument beautifully in What Technology Wants, noting how 100 years ago, the number of items in your house was considerably less than now. Technology innovation has led to abundance.

While a precise metric for innovation (for example, a way to quantify the pace as a number) is difficult to capture, the trend is clear: 2,000 years ago, there might have been 1 major invention every 50 years. Today, significant inventions seem to appear every 1 year or sooner. The timespan just keeps shrinking.

If the pace is accelerating, companies need all the resources they have just to keep up. By replacing human workers with AI, they risk losing the speed needed to run at the faster clip that others are moving at.

For example, let’s say that pushing out one major feature a month per software team was the norm in 2025, but in 2027, the company is expected to push out 3 major features a month just to keep pace with an increased speed across the tech landscape. In 2030, you need to release a major new feature each week in your software product. By 2035, your product will practically need to be perfect and perform miracles to move past competitors in the market.

In a state of accelerating change, we need AI tools just to keep our head above water. If your company can’t push out new and better tools, they’ll be eclipsed by those who can. If CEOs operate with a mindset that thinning their employees will yield more profits because they can accomplish the same output with two-thirds the number of people, that commits the fallacy of thinking that the goal posts are staying in the same position. The competitive environment is intensifying. The release windows in which you must push out new software are shortening and becoming more frequent.

How will companies keep up? If a small, nimble company can release a disruptive innovation overnight, they can quickly eclipse the incumbent companies. Maybe in the short term, a company like Amazon can lay off large numbers of tech workers and it won’t matter for a while. But think 3-5 years down the line. Will the same company have the tech resources to keep their competitive edge in a landscape that is accelerating with faster releases, speeding up their development cycles to release new features and products more frequently? If the race is getting faster, a company that chooses to reduce the power of its engine will slow down.

Even tech leaders are openly acknowledging this acceleration reality. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, speaking at the US-Saudi Investment Forum in November 2025, directly contradicted the liberation narrative when he said: “I would say that there’s every evidence that we will be more productive and yet still be busier because we have so many ideas.” Huang pointed to radiologists as an example, noting they’re now processing more scans than ever before thanks to AI—not fewer. As he put it, “everyone’s jobs will be different” as AI creates more business concepts and projects to pursue. Rather than freeing up time, increased productivity simply generates more work to fill the new capacity. (Nvidia CEO Says Instead of Taking Your Job, AI Will Force You to Work Even Harder)

Hard limits to velocity

A counterargument might be that an existing tech writer’s output will grow commensurately with technological innovation. For example, in 3-5 years, the same tech writer who was producing 5 documents a week will produce 10.

That might be partly true. However, the idea that a reduced body of employees will commensurately keep pace with accelerating industry change seems unlikely. This is because there are some hard limits to speed that happen even when you apply AI as much as possible. AI’s speed is mostly with content generation, not content validation. As a result, you end up with a lot of generated content, but the validation processes (the human in the loop to review and check the AI output for errors) aren’t moving at the same speed.

This is something I’m wrestling with in the bug zero series that I’ve been writing about. Theoretically, AI should allow me to reduce my doc issues from 40 tickets to 0 tickets. However, I’m not seeing how to use AI in a way that would allow me to achieve that level of speed. I want to, for sure. Often when I turn around someone’s large doc request in record speed, they give me a peer bonus. I feel like a laggard when their requests sit for weeks or months in my queue.

Why can’t I speed up my documentation writing velocity to clear out the doc queue? Two reasons. First, because the requests are coming in at a faster clip (tech is accelerating). And second, because although AI speeds up content generation, it doesn’t speed up the validation process—the review and verification, along with issue tracking and work management.

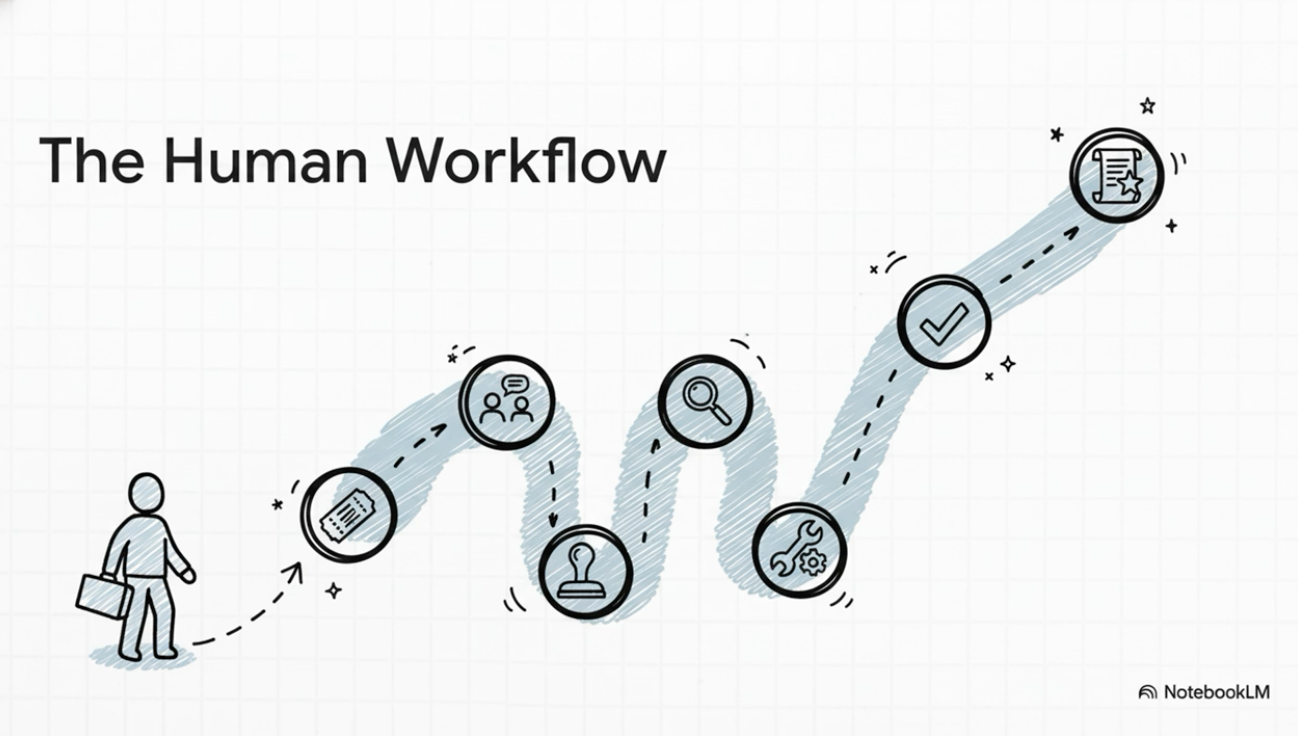

Even the simplest task, like fixing a broken link, demonstrates this acceleration ceiling. While AI might help identify or fix the link itself (perhaps it’s a tricky Javadoc package reference), that single step is a fraction of the total work, which includes the following:

- Create a bug in our ticketing system.

- Identify the source file containing the error.

- Make the updates to the content.

- Create a changelist with the updated file.

- Identify the SME reviewer who has ownership of the directory.

- Describe the update in the changelist.

- Stage the changelist and provide a preview link.

- Ping the SME to review the changelist.

- Address any comments from the SMEs.

- Pass any presubmit tests for the changelist.

- Wait for the SME to approve the changelist.

- Submit the changelist.

- Verify that the changelist correctly propagated into production.

- Describe the update in release notes.

- Relay the update in internal reports.

Maybe a smarter AI system could automate all these steps. In fact, I plan to try to tackle each one and see how it might be automated. But such automation is difficult. For example, automated reminder messages sent to SMEs are likely to be ignored. Automated changelist descriptions might correctly itemize what’s changed, but without more context the descriptions might fail to communicate the “why” behind the changes.

One approach to breaking through the acceleration ceiling is to incorporate smarter error checking tools at key points in the workflow. We already have some in place, and I’ve also introduced my own custom checkpoints. When I submit a changelist, Gemini looks over the file changes to see if the changes match the bug, examines configuration errors or other problems in the changes, and flags any issues to fix. This is usually helpful and more often than not catches issues I miss.

I also use my own verification on content by asking Gemini to check the content against the API reference. This usually works well too, though I frequently run up against token constraints due to the size of the APIs, along with needle-in-the-haystack findability problems. Also, it doesn’t make sense to check every CL against the API (such as the link fix CL), so there’s a human judgment call here about which verifications are needed for which content updates.

Even with AI assisting the validation process, there are many workflow process steps that can’t be sped up, so each ticket has its own bandwidth constraints regardless of the AI involved in the content generation and verification. This means there’s a ceiling to expected velocity gains. Maybe 7 documents a week is that ceiling. Any attempts to go beyond that speed, such as by reducing the review time or reducing reviewers, means accepting a greater risk of error.

Increasing speed means risking more error

Going faster means risking more error. It’s like driving a car: If you’re going 20 mph, your risk of collision is low. Go 120 mph, though, and a crash is almost certain.

This is where a company starts to incur “productivity debt”: borrowing time by cutting corners on validation, only to pay it back with interest later in the form of rework. Even consider a small doc update that contains an error. When you float this doc update to engineers to review, they won’t approve the changelist due to the error (assuming they catch it). The error can trigger a whole cascade of back-and-forth discussions/interactions on the changelist. You have to look at their comments and interpret them, update your content, resubmit it for review, and so on. Errors slow everything down.

It’s even worse if the error slips by reviewers and makes it into production. Now partners might see the errors and communicate them to field engineers, and so on. Every error reduces trust in the documentation and your professional capabilities. So errors aren’t good. Taking time up front to eliminate errors (the validation process that bottlenecks AI’s speedy content generation) actually speeds up the pace of documentation overall.

How do you speed up without allowing for greater risk of errors? Let’s assume the pace has really picked up so that each tech writer is publishing not 10 but 100 documents a week. Now you really have less time to diligently review each change. You might only have time to quickly skim incoming changelists to review, hoping that the updates are right. You’d need to trust the AI output more because you don’t have time to test or verify it against a source of truth.

You hope that reviewing engineers will do the validation, but they too are sped up. They’re probably relying on the same AI tools to check the content that you already used, creating a dangerous validation loop where no human is actually performing the primary check.

A world sped up

To recap my argument, yes, AI can accelerate our output, but it won’t liberate us. AI is accelerating everyone’s output. Not just you and your colleagues’ output. It’s accelerating the output from your competition, both nationally and internationally. The world has sped up.

In a state of accelerated innovation, we need AI tools just to keep our head above water. If your company can’t push out new and better products, they’ll be eclipsed by companies that can. If CEOs thin their number of employees, thinking it will yield more profits, that short-term thinking commits the fallacy of assuming that the goal posts are staying in the same position.

The release windows in which you must push out new software are shortening and becoming more frequent. Expectations about quality are increasing. You have to spend more time in research and development to ensure the competitor’s next release doesn’t put you out of business. This is why company layoffs might be a strategically poor decision: in an attempt to capture short-term profits, they shed the human validation resources needed to compete in the long-term, accelerated race.

A new AI narrative

Returning to the original idea of this post, what should the AI narrative be? Instead of this liberation narrative:

AI does the tedious tasks so you focus on more strategic work.

it could be:

AI provides tools to speed up your work in a constantly accelerating environment.

But no one likes acceleration as a goal here. We’re all accelerating and reeling from its effects. The idea of AI as liberation—liberation from all the tedious and time-consuming tasks you have to do—sounds much more appealing. But that liberation is a false narrative. AI isn’t liberating us. It’s speeding up the race. And we’re out of breath.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.