Thoughts on ChatGPT after reading Crawford's Why We Drive: whatever skill you outsource, atrophies

- Crawford’s Why We Drive and automation

- What we outsource, atrophies

- Let’s switch from driving to writing

- Luddite?

- Conclusion: Weighing tradeoffs

- References

Crawford’s Why We Drive and automation

In Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road, published in 2020, Matthew Crawford blends philosophy and personal experience in compelling ways to explore what happens when we outsource our agency to machines, choosing automation instead of individual action. Cars are becoming increasingly more computerized, with more driver assistance features (from lane centering to adaptive cruise control, self-parking, ABS, autopilot, and more). Crawford believes that automation removes many of the human elements from driving, converting the experience once perceived as the epitome of freedom and mobility to one in which our decisions and actions take a backseat to the will of the machine. We have replaced real experiences with manufactured experiences, Crawford says, cocooning people from the satisfaction of pushing back against the world with some form of mastery.

Crawford wrote Why We Drive while autonomous vehicle development plans and hype were going strong; many thought we would soon transition to driverless cars, or that driverless Uber fleets would be in full production. Crawford’s Why We Drive is a rebuttal to this trend, pushing back against automation that replaces human decision-making, acting, and thinking. Crawford explains:

What, then, is so special about driving? That is the animating question of this book. In trying to answer it, I will be attempting something like “philosophical anthropology.” For driving is a rich and varied practice. As with any such practice, a full consideration of it can focus light of a particular hue on what it means to be human. It can also shed light on the challenge of remaining human against technologies that tend to enervate, and claim cultural authority in doing so. (7)

In other words, Crawford selects driving because it’s an example where automation reduces the human experience of the activity. Other activities might have likewise served the point, but driving in particular expresses a special freedom and autonomy that we have celebrated. When you’ve felt the exhilaration of control over your mobility, of having the ability to go wherever you want, as fast as you want, when you want — it’s exhilarating.

When automobiles were first introduced, they unlocked mobility for rural-based families, such as farmers, to travel outside their communities and come into the city. Crawford says this sense of freedom creates much of the joy of driving:

Life often feels overspecified, fully modeled and determined, but the road has a dicey quality to it. We usually have a destination in mind, but when we get behind the wheel we expose ourselves to unexpected hazards, as well as unlooked-for moments of discovery. On a road trip, you encounter landscapes and human types beyond the ken of your usual routines, and there is something rejuvenating about this. It reminds you that there are possibilities you hadn’t reckoned with, lives you could have lived — or might yet.” (8)

Driving offers a sense of spontaneity and freedom not available in other activities. To travel unfamiliar roads without a clear destination other than to explore and discover new areas, or to follow a curiosity and drive to a new place — this autonomy offers a sense of randomness and play that delights us.

We drive to express our freedom, and this freedom makes up a core aspect of our human identity. Crawford says, “…our mobility as self-directed, embodied beings is fundamental to our nature as it has evolved over millions of years, and to the distinctly human experience of identity” (14). From nomads to other community groups that moved from place to place, we hold personal mobility high up in our list of human behaviors.

Automated driving removes many of these elements. How do you go to a random place in an autonomous vehicle (AV) that doesn’t have a steering wheel? You don’t. Cars become entirely utilitarian machines in which you input a destination for a specific transportation end.

Crawford says the marketing pitches for AVs usually depict the passengers, freed from the monotony of driving, instead catching up on poetry and interacting with other family members. This free time, however, will more likely be occupied by checking email, completing Wordles, and playing Candy Crush, all while you’re exposed to more advertising. Instead of pondering T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of Alfred Prufrock,” the AV rider “will spend these minutes irritably sifting through offers of various products and services tailored to his creative lifestyle and to his intended destination, conveyed through the same table interface, each of which must be declined before the car will proceed on the route he had in mind initially” (39-40). How many people use ChatGPT to bang out a report so they have more time to read Shakespeare?

Crawford distrusts the motivation behind automation, seeing it as a demand-engineering project of big tech, intended to carve out yet another space to insert itself into our lives. Crawford embraces Shoshana Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism and raises many points about how big tech, through data collection, nudges and herds us in their directions.

Overall, Crawford celebrates driving as an activity that requires thought, skill, and mastery:

The pleasure of driving is the pleasure of doing something; of being actively and skillfully engaged with a reality that pushes back against us. Only then do we feel the progress of our own mastery. In skilled activities, we sometimes recover the joy of childhood play, that period in life when we were discovering new powers in our own bodies. (115)

In other words, we thrive in this interaction in the automobile — manipulating wheels, levers, and other functions against a sea of other cars, roads, and navigation. The challenge invigorates us. With automation, however, that experience gets reduced. We become cocooned from reality, packaged and transported like a commoditized good.

What we outsource, atrophies

What stands out to me most in Crawford’s book is this: as we automate an action by offloading it to an external machine, our ability to perform that action atrophies. This has become increasingly acute with the release of generative AI models that can create graphics and written content. I’ll get to that in a minute. First, let me explain more about the atrophying of our skills. Crawford says:

The technocrats and optimizers seek to make everything idiot-proof, and pursue this by treating us like idiots. It is a presumption that tends to be self-fulfilling; we really do feel ourselves becoming dumber. Against such a backdrop, to drive is to exercise one’s skill at being free, and I suspect that is why we love to drive” (31).

For example, GPS navigation removes a cognitive task from driving, snuffing out any wayfinding skills as drivers mindlessly follow the blue line on their smartphone or embedded screen. In this mode, we become automated by the automaton. Crawford says:

…with GPS navigation, are you much required to notice your surroundings, and to actively convert what you see into an evolving mental picture of your route? Between the quiet smoothness, the passivity, and the sense of being cared for by some surrounding entity you can’t quite identify, driving a modern car is a bit like returning to the womb. (5)

Have you noticed that the more you use GPS, the more you actually need GPS? I wrote a few posts on wayfinding a while back. I spent more than a year routing to a Safeway with Google Maps that was merely 1.5 miles from my home because the confusing turns never stuck in my memory. It wasn’t until I actively abandoned my mapping applications that I learned the logic of streets in my city. Wayfinding is a skill one loses the more it is outsourced to computers.

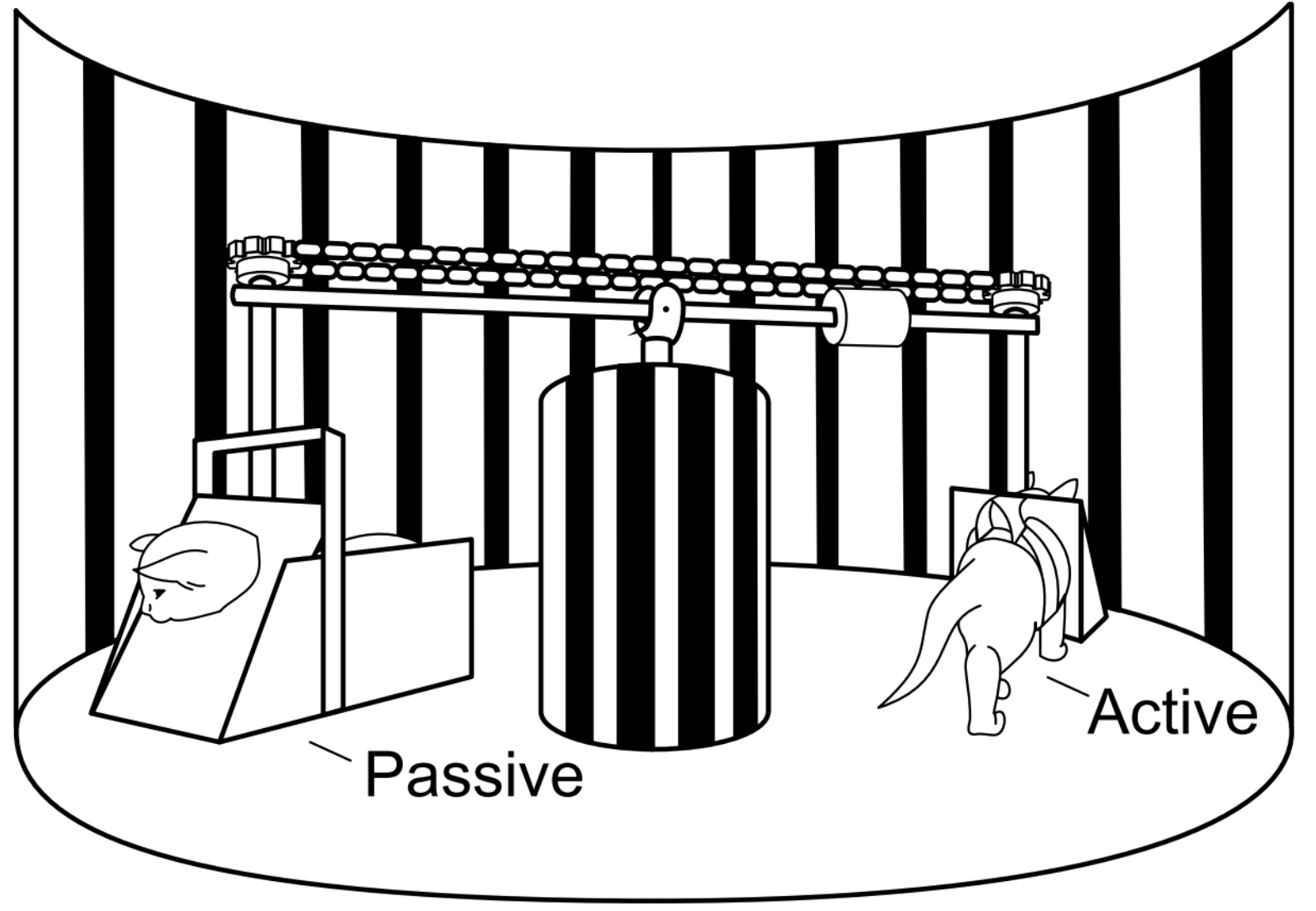

Wayfinding is just one skill among many lost in automation. Crawford relates a carousel experiment with kittens that determined their motor development. In one scientific experiment, researchers (Held and Hein, 1963) made one group of kittens active controllers of a roundabout carousel car, while making the other group of kittens passive and unable to control it. “The active kittens developed normally; the passive kittens failed to develop visually guided paw placement, avoidance of a visual cliff, a blink response to quickly approaching objects, or visual pursuit of a moving object …” (61). In other words, the physical act of manipulating the carousel, controlling their mobility, led to key motor development that didn’t happen in the passive kittens.

Continuing in this direction of automation, with driving, the more we abdicate our skills, the more those skills atrophy until we lose the capacity to drive at all. At that point, all the safetyist messaging about human drivers being poor drivers and needing machines to do the driving will actually be the case. It’s self-fulfilling, Crawford says. “What is at stake is not simply a legal right, but a disposition to find one’s way through the world by the exercise of one’s own powers” (10-11). With fewer skills and capability to drive, we lose interest in it.

On a more biological/physical level, our ability to navigate our environment affects how our brain and memory structures grow. Crawford explains:

Navigating space and exploring our environment influence how the hippocampus develops, and this structure at the center of the brain is where we develop our cognitive maps of the world…. Time and space are connected in experience, and therefore also in memory. And it is only after the brain becomes capable of place learning, through the slow development of the hippocampus (via roaming self-locomotion), that we begin to retain episodic memories.” (12-13)

In other words, our sense of space and environment provides a foundation for memories to form and have context in the brain. If automation reduces place learning, will other parts of the brain likewise be affected?

Let’s switch from driving to writing

With this perspective (what you outsource, atrophies), let us now shift to the automation trend of the day: language-generative AI with ChatGPT. (GPT stands for generative pretrained transformer and refers to the language models used to train the AI.) Exploring the OpenAI Playground, which uses similar GPT-3 APIs as ChatGPT but with more custom controls (such as choosing which model to use, how long the responses are, and other toggles), I was dumbstruck by how the AI bot could perform writing tasks in advanced ways. We’ve been using simple grammar and style checkers for years to identify misspellings or confusing syntax, but suddenly AI bots moved light years ahead of these tools. The AI bots allow you to write an entire essay (sounding intelligent and articulate) from a rough list of bullet points. You can paste in large chunks of text and have the AI bot instantly convert the content into graceful language. Or you can have it alter the tone of your writing, injecting excitement or other emotional elements. You can make your essay sound like Hemingway, or like an obscure scholar, all with the click of a button.

I’m usually in favor of adopting tools that will help with writing. Who wants to read and reread the same content over and over looking for typos or making a thousand micro-adjustments to smooth out the language and make the ideas flow? It can be tedious and mind-numbing. So as I started writing this post, I actually tried to use the AI bot to do it all for me. I started writing some rough sentences, making no effort to really articulate the ideas in any fluid way but just getting the ideas out; then I asked the AI bot to fix and smooth everything.

It seemed to be working all right, but things quickly veered off track. The AI bot’s wording was too bland, so I made it more punchy. But then it didn’t feel like mine. They weren’t my words anymore. And with the AI doing the writing, the post didn’t stick in my mind. It didn’t compel me (no bee in my bonnet). It wasn’t something I thought about and felt motivated to write and finish.

Part of the writing process is sorting out an idea for yourself, helping you think. If we outsource that thinking process, it atrophies in us. It’s the equivalent of plagiarizing an essay in a college class — if we bypass the writing task, we skip out on all the critical thinking skills we would have otherwise developed.

The larger point is this: the finished post isn’t the purpose of writing. The writing process is the purpose. The journey, not the destination. The act of writing, not the published post. By skipping the journey, skipping the writing, the whole act of writing loses value and becomes far less interesting.

Using the AI bot, my muse spoke less. I didn’t have thoughts on the back-burner continuing to process and sort out in my unconscious mind. I didn’t find myself suddenly experiencing a moment of epiphany while doing some other task (and suddenly stopping on the sidewalk to record it).

Another element missing: the spark of discovery, the unplanned detour that happens mid-way through a post as you come to some new realization about the topic. This spark of discovery is what usually makes writing “hot,” or what makes it compelling to read. The discovery is the realization element that creates the arc of a story as well. The AI bot isn’t good at injecting a spark of discovery; at most, it might incorporate a bizarre fictional element if you specifically request it, but the AI bot isn’t good at coming up with new ideas. You can’t just tell it to come up with a unique realization or thought about a topic. It’s all mimicry from the language model.

The written output from the AI bot didn’t feel like the product of my labor. Further, I had to constantly read and reread sentences to make sure that the bot didn’t distort anything.

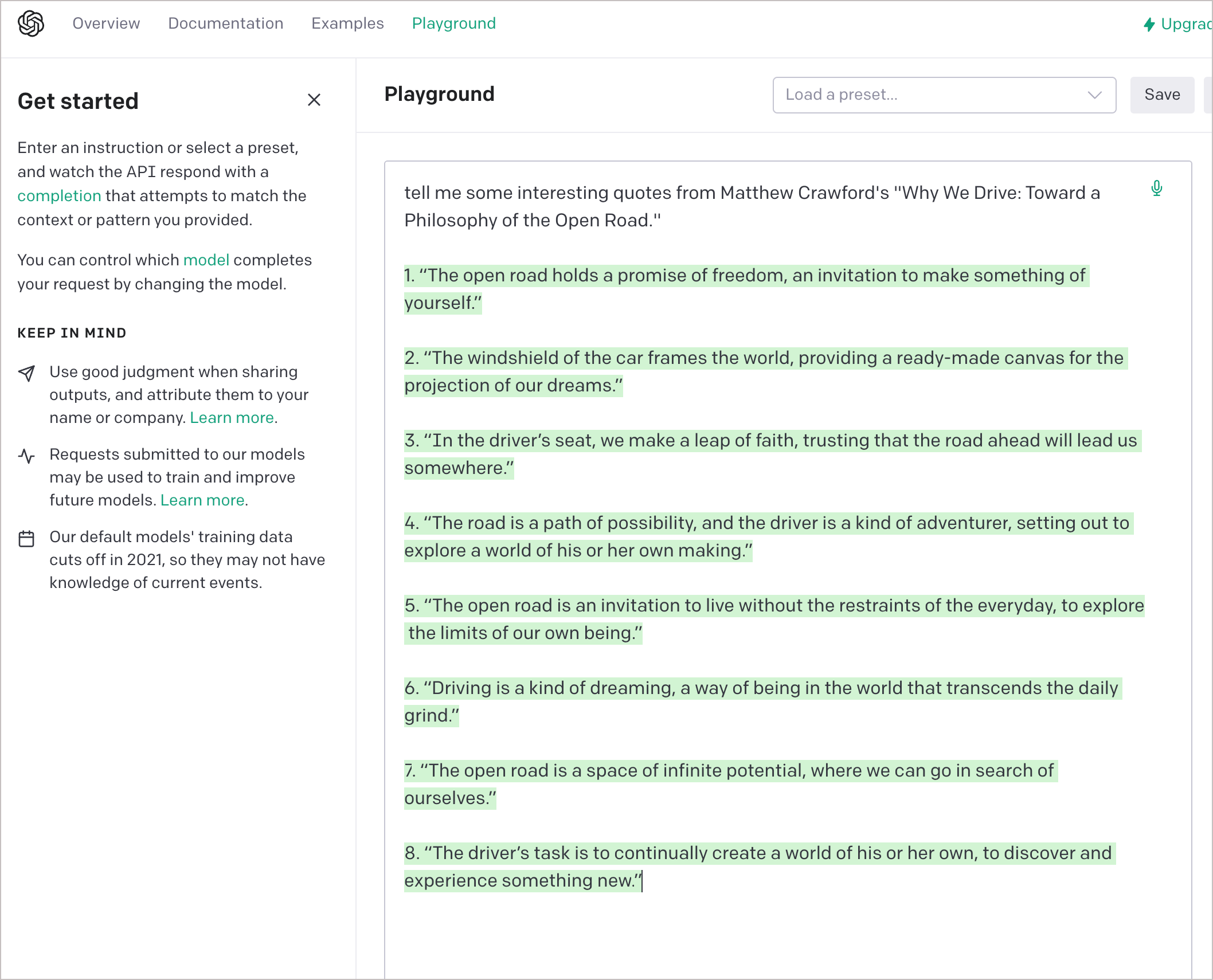

But there’s another major flaw in using the AI bot: its uncanny ability to make details up. If you ask it for quotes from a book, the bot (at least on OpenAI Playground) will literally invent quotes that sound like they might come from the book but don’t.

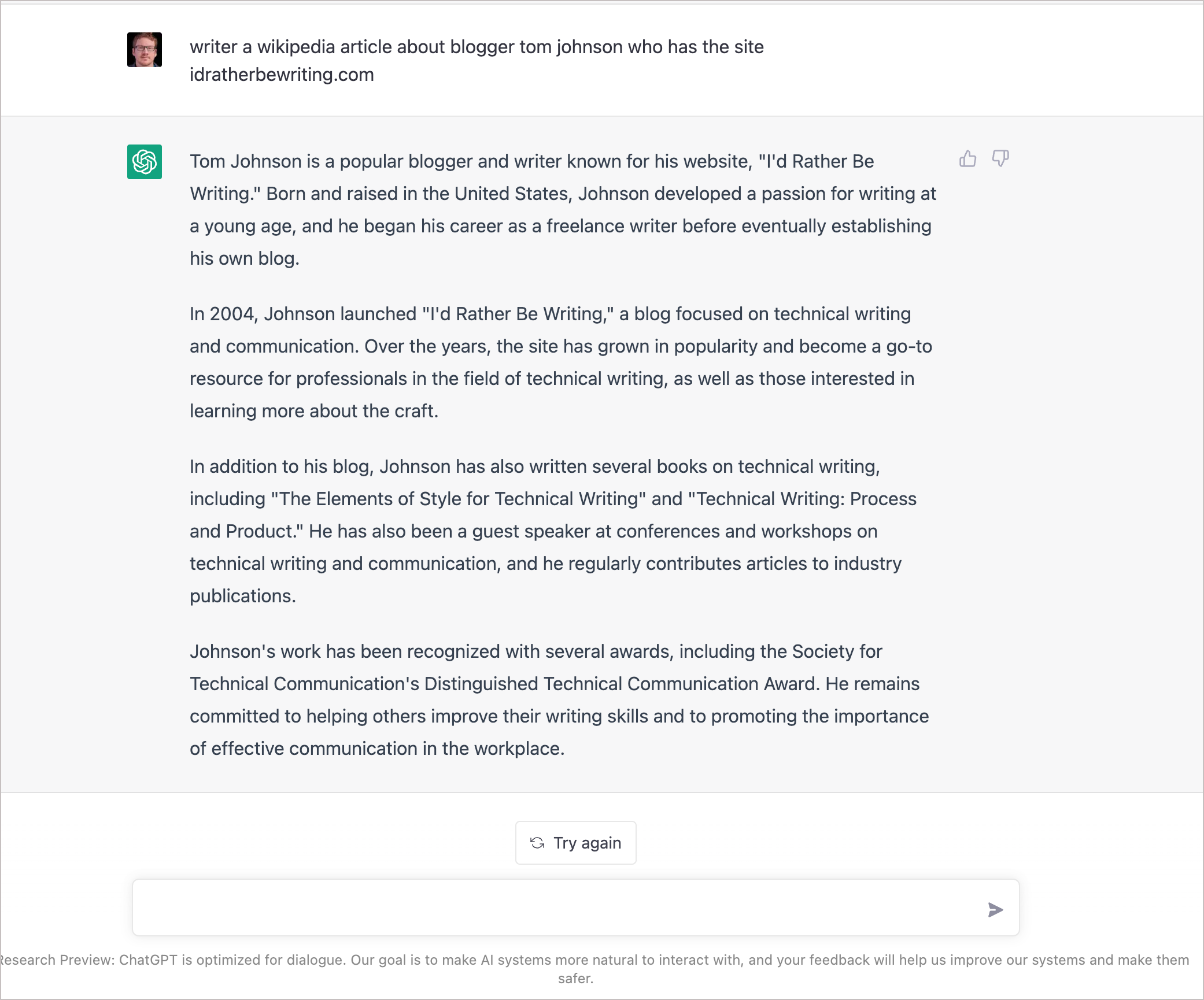

I noticed that the AI bots on the OpenAI Playground make a lot more details up than the AI bot on ChatGPT. Even so, ask ChatGPT to write a wikipedia article about yourself and then ponder the details:

It’s well-known (to AI-savvy people) that these bots fabricate, but it catches many by surprise. In “The New Chatbots Could Change the World. Can You Trust Them?” the authors note that these chat bots “do not always tell the truth. Sometimes, they even fail at simple arithmetic. They blend fact with fiction. And as they continue to improve, people could use them to generate and spread untruths.” See also this other post on Hackr News: “ChatGPT produces made-up nonexistent references.”

Why does ChatGPT make up quotations that don’t exist, without letting on that the quotations aren’t real? Supposedly, it’s because the bot’s responses are based on predictions from language associations, not from raw material crawled and indexed and stored in its memory. Even so, apparently, even experts aren’t quite sure how generative AI works (see “Can ChatGPT make this podcast?”).

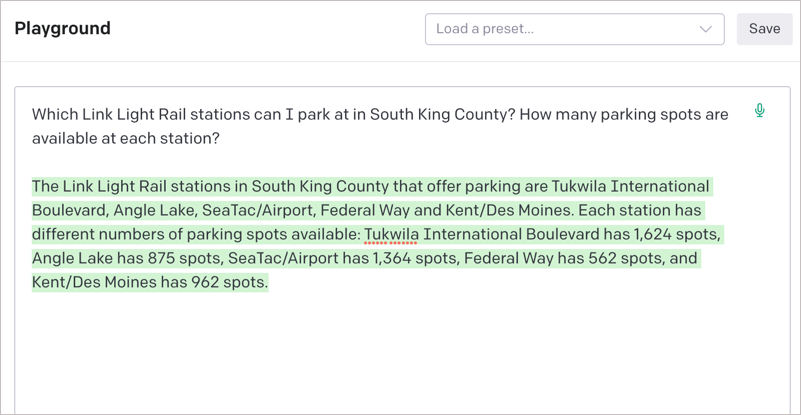

Here’s another example:

The unreliability of information changed my usage of the AI bot. As I attempted to write this post with AI, I asked the bot to list some other books related to this topic. As I mentioned, with this request, it would return nonsense books that it invented. But with some tweaking of the question, it also suggested Kevin Kelly’s The Inevitable (a real book) as another book addressing similar themes. I asked the bot to summarize key points from Kelly’s book about the effect of AI tools on writing, but it wasn’t clear whether the bot was accurately delivering this info or making it up. I couldn’t just summarize other texts that I haven’t read, trusting in generative AI’s accuracy, knowing that bots fabricate.

Also, when you start asking the AI bot more specific questions, like what’s the point of the demolition derby story in Crawford’s book, or what are key points in such and such chapter, the AI bot does an impressive job of making up something that sounds plausible while not letting on that it’s entirely bullshitting. Many times the info is legit, but how do you know? Don’t get me wrong — it’s still impressive (it’s trained to seem believable), but it’s unreliable. It’s a prediction engine that constructs responses based on what language it thinks will complete the sentence. In writing scenarios where I’m creating a blog post with my name, brand, and reputation associated with it, the unreliability element is problematic.

Luddite?

I don’t want to come across as a Luddite here. I’m all for using tools to assist the writing process, especially in identifying spelling and grammar errors. And of course, I don’t want to be left behind if everyone else adopts this tool. I do like how the AI bot can smooth out language and make things more readable. Its ability to distill long passages into short summaries is also useful. Perhaps it could also act as a kind of intelligent reviewer, analyzing your argument or identifying weaknesses in the content you supply it.

But if we start using AI Bots more extensively in generating the raw content itself, we can expect the same results as any other automation: the more we outsource, the more we lose the ability to perform the skill ourselves. Or to use a more familiar phrase: if we don’t use it, we lose it. And that future, in which writing becomes a lost skill (as rare as the ability to wayfind without a GPS app), has unsettling consequences for writers.

Coming up with original ideas is a key reason to keep writing with our own typing fingers. Generative AI writing will likely involve an echo chamber in which new writing is merely an imitation of everything online. And then, as the Internet gets populated by generative AI, the AI bot’s output will become a looping imitation of itself (as the language model is trained with its own output).

Additionally, if the AI bot starts doing the heavy lifting, writing itself becomes uninteresting. The act of writing through the AI bot — feeding bullet points into a machine to organize and synthesize and articulate the ideas — reduces the activity to something far less engaging. Writing becomes a bore, an activity we abandon. It’s kind of novel and amusing at times. But overall it becomes a mechanical process of pushing buttons and strategically feeding it the right prompts to produce the right results.

If we abandon writing, that clever ability of our brain to make connections, to express itself in language, and to ruminate on a thought until we see it through to some written expression becomes a lost capability. This is the paradox of generative AI: the more it helps you write, the harder it becomes to write. Eventually, the part of the brain once actively involved in writing shudders its doors and puts up a Closed for Business sign.

Conclusion: Weighing tradeoffs

I’m not sure if AI bots will be a passing novelty or an invaluable writing tool. In another book I’m reading, May I Ask a Technical Question, authors Jeff Krinnock and Matt Hoff encourage us to examine the effects of the technology we incorporate. They say “we need to measure the digital wonders showing up continually in our lives not simply by their abilities and the tasks they perform for us, but also … we need to measure and consider what human and social tasks, abilities, traditions, skillset, and opportunities they displace” (39). Their book fits into the growing genre of cyber skepticism. What human skillsets and abilities will generative AI models displace as they write for us? Will the effect be similar to cars that drive for us?

Evaluating whether to incorporate a new technology into our lives is also a theme Kevin Kelly explores in What Technology Wants. Kelly explains that growing up in the 50s and 60s, he observed how television became a trending technology used by his friends:

The technology of TV had a remarkable ability to beckon people at specific times and then hold them enthralled for hours…. They obeyed. I noticed that other bossy technologies, such as the car, also seemed to be able to get people to serve them, and to prod them to acquire and use still more technologies…. I decided to keep technology to a minimum in my own life. As a teenager, I was having trouble hearing my own voice, and it seemed to me my friends’ true voices were being drowned out by the loud conversations technology was having with itself. The less I participated in the circular logic of technology, the straighter my own trajectory could become. (2)

In other words, some technologies have the potential to mute our own voice. Much of Kelly’s book is a deliberation about what technology we should adopt into our lives, whether it’s inevitable to adopt it and what changes will result. After some deliberation, Kelly mostly embraces technology, saying it expands our options with more freedom. Is ChatGPT expanding our creative freedom in powerful ways, allowing us to express ourselves in more powerful ways? As Emad Mostaque of Stability AI says, is generative AI “one of the ultimate tools for freedom of expression” (“Generative A.I. Is Here. Who Should Control It?”)? Apparently, Mostaque believes “So much of the world is creatively constipated, and we’re going to make it so that they can poop rainbows” (“A Coming-Out Party for Generative A.I., Silicon Valley’s New Craze”). Are these AI writing bots limiting our freedom by reducing our own abilities? By atrophying our creative abilities, are they paradoxically reducing our freedom (like drivers bound to GPS because their wayfinding skills have weakened so much)?

Few technologies have challenged writers more than the emergence of generative AI tools for writing. The reactions have been so extreme, some are wondering whether generative AI can replace technical writers altogether (along with other professionals, like therapists, and other companies, like Google). ChatGPT is based on GPT 3.5. Apparently, those who have used GPT 4, to be released next year, come back with wide-eyed looks as if they’ve just seen God. My hunch is that many people will start using language-generative AI like ChatGPT in the same way I use generative image AI (Midjourney, DALL·E) to create decorative images for this post: as a way to offload a task I don’t want to perform myself.

I’m not seeking to become an artist or illustrator, but I know that people dislike long walls of text. I generate the images to create more of a balance of visuals and text. But make no mistake: my own illustrative skills (already dismal) have probably weakened since doing this. In no way does generating images through AI tools further my career as a graphic designer.

Another point: The AI-generated images don’t need to be exact, just somewhere close to echoing similar themes I’m writing about. In contrast, language must be much more precise. It’s not good enough to generate kind of similar ideas or thoughts. Text has more potential for misinformation, while art has the potential for just being weird and surreal.

The same fate of generative AI images and graphic designers will likely happen with AI bots and writers. For those who dislike writing and just want a tool to perform the task they don’t want to do, it will work fine. Need a quick way to summarize the latest research on a topic? ChatGPT will do. Need a quick decorative image to reinforce a theme you’re exploring? DALL·E will work fine.

But if you want to further your own writing skills and talents, the quickest way to kill that ability is to use another tool to do it for you. This decision isn’t merely the equivalent of using a calculator to avoid doing long division, freeing you up for more complex tasks. With writing, the act of writing includes thinking, synthesizing, problem-solving, and more. When we skip all that, creating the end output with the push of a button, we put those same thinking functions within ourselves to sleep.

The challenge in the coming year will be to figure out how to leverage AI bots as writing assistants without letting it smother our writing abilities. In other words, how can we use the bots as figurative calculators to free us up for more complex writing tasks? What would those more complex writing tasks look like?

Maybe AI bots will force writers to move to another level higher, like two companies with competing products. No more cliche observations or lightweight content. If the AI bot can guess the list of points you’re making about a topic, you need not bother writing it. In this way, AI bots might force writers to climb to a deeper level of thought beyond the capacity of the bot.

References

ChatGPT produces made-up nonexistent references. Hacker News. 3 December 2022.

Crawford, Matthew B. Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road. HarperCollins, 2020.

Kelly, Kevin. What Technology Wants. Penguin, 2011.

Krinnock, Jeff, and Matt Hoff. May I Ask a Technical Question?. 2016.

Metz, Cade. “The New Chatbots Could Change the World. Can You Trust Them?”. The New York Times. 10 Dec 2022.

Roose, Kevin, and Casey Newton. Can ChatGPT make this podcast?. The New York Times. 9 Dec 2022.

Roose, Kevin, and Casey Newton. Generative A.I. Is Here. Who Should Control It?. The New York Times. 21 Oct 2022.

Roose, Kevin. A Coming-Out Party for Generative A.I., Silicon Valley’s New Craze. The New York Times. 21 Oct 2022.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.