Turning Point (Wikis)

I tried the volunteer writing model for more than a year. I kept thinking that if I just figured out the right approach, it could take off into endless productivity. With 100+ writers creating content on a regular basis, we could publish new blog posts daily. We could translate documentation overnight. We could sketch out a skeleton of tasks to write about, and then have volunteers fill in the details. It didn't happen.

The reasons, as I have stated, can be summarized in three bullet points:

- Writing requires insider knowledge that volunteers lack.

- Professional writing standards are usually beyond volunteer capabilities.

- The management overhead in coordinating volunteer writing barely outperforms the return.

This marked a turning point for me in using wikis as a collaborative platform.

With wikis, I did like the publishing immediacy and the web interface, but Mediawiki had so many shortcomings that the platform didn't seem worth it without having an overwhelming need to collaborate.

With Mediawiki, I couldn't publish to any other output other than web. With Flare and other help authoring tools, you can publish to PDF, Webhelp, EPUB, Mobile, and more. Given the proliferation of mobile and tablet devices, it seems that technical writers will need to master multi-device publishing if they are to remain relevant. With that, I switched back to help authoring tools and wrote a post, When Wikis Succeed and Fail.

Switching back from wikis to traditional help authoring tools

Switching back from wikis to traditional help authoring tools

Time for Another Model: Testing Documentation

Despite my apparent failure with wikis and engaging volunteer efforts, I have not thrown in the towel on volunteer efforts. I do think another model may be more productive: crowdsource documentation testing.

Our biggest success in LDSTech by far has been with testing rather than development. Testing a software application across the variety of platforms (iOS, Android, BlackBerry, Windows), carriers (AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile), locations (North America, Europe, Africa, South America), roles (clerks, bishops, stake presidents, auxiliary leaders, members, website administrators), computers (PC, Mac, other), operating systems (Windows 7, Windows 98, Mac OS, Linux), browsers (Opera, Safari, Chrome, Firefox, Internet Explorer 6,7,8,9), and scenarios (so many possibilities) is pretty much impossible to do in-house.

The in-house quality assurance team can test general load and general requirements for the software, but testing all of the possibilities of user experience proves impossible under normal budgets.

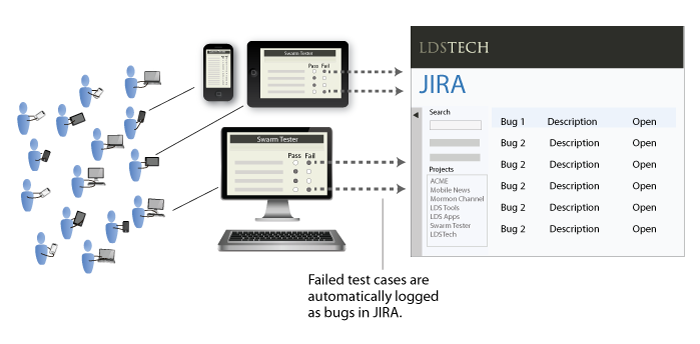

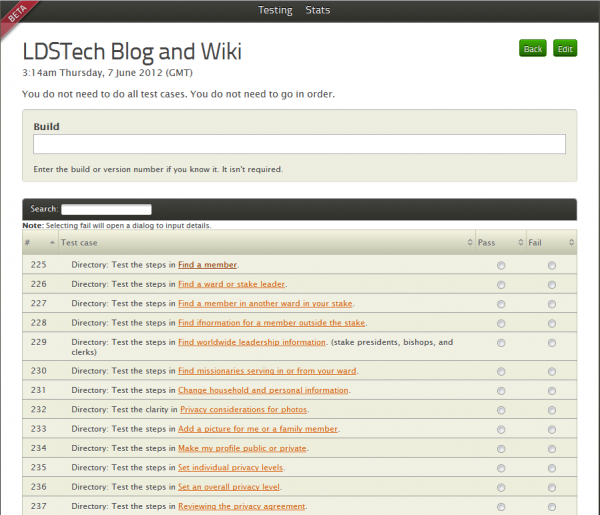

Because of the success with testing, our team decided to build a tool that would facilitate more directed testing. The tool was just released a couple of weeks ago, and it's still very new. But here's how it works. The testing lead enters a list of specific test cases he or she wants the crowd to test. Users can respond to the test cases with pass/fail options. If the user marks the test case as fail, he or she is prompted for a reason why. The failed responses are automatically appended to JIRA items.

When multiple volunteers report a failure for the same test case, the failures are appended to the same JIRA item, thus removing the chaotic mess in the forums where responses about bugs appear across a variety of threads.

The tool was designed for testers to test software functionality, but it also works with documentation (documentation is, after all, part of the product). Each task functions similarly as a test case in software. If users cannot complete the documentation's steps, they can mark the task as fail and explain why.

For the following reasons, testing documentation may prove to be the biggest win for writing within the community:

- Testing documentation does not require insider knowledge.

- Testing documentation does not require professional writing skills.

- Testing documentation does not require a lot of time from volunteers.

Additionally, through the crowdsource testing tool, which we call Swarm Tester, the feedback can be neatly organized.

First Experiences with CrowdSource Testing

Although it's still too early to tell, my experience with crowdsource documentation testing has been positive. I am getting just the kind of feedback that I truly want. With one of the applications we have help for, I created a link to each individual task. The application was rather light, so I just created about 25 links. The test cases outlined that people should test the steps in the documentation. If tasks did not have steps, users were to test the clarity of the information.

It's only been about a week using this model, but so far I've found that many participants who didn't write articles did in fact participate in reviewing the documentation. Their comments were helpful and on target. I hadn't updated the application's help for about a year, so there were clearly some parts that were out of date.

Interestingly, one team member decided to simply update the inaccurate information directly on the wiki, because, after all, it was editable. Most of the others, however, made recommendations for changes. Within a week, about six different volunteers tested the documentation in ways that proved very helpful.

Rather than struggling to edit a volunteer-written article, or figure out a topic that volunteers could successfully write about, or figure out how to connect the volunteer with the right information, I could focus volunteer efforts on well-defined tasks that didn't require any writing or knowledge. All they had to do is try the task and provide feedback. It was perfect.

Some Limitations with Crowdsource Testing

There are a few complications with crowdsource testing. For starters, not everyone can test every role. Unless you can supply sample roles for users to log in and use, some users may not be able to test functionality because their role lacks the appropriate rights.

Another complication is that directed testing removes the spontaneous exploration and discovery that users might have in browsing an application. By specifying all the cases we want users to test, we may overlook the many cases that users don't test because we put figurative blinders on the users. Failed reports will only give feedback about identified tasks, not those tasks that users do but which do not appear in the help.

Finally, using a crowdsource testing tool does not leverage the writing capabilities of the crowd. Anyone can test a task or procedure without leveraging any particular writing talent at all. In that case, it's not capitalizing on writing at all.

Even with these complications, I feel that I have hit the sweet spot in leveraging community contributions with documentation.

Conclusion

As you can see, I have moved from using a traditional help authoring tool and writing alone to a more collaborative authoring environment based on a wiki platform. Despite my attempts at getting volunteers and others to write, the efforts largely stagnated and weren't worth the management overhead. Because collaborative writing failed, I didn't see any need to continue using wikis as a platform, since help authoring tools could provide more robust outputs in different formats.

However, rather than abandon community and collaboration altogether, I instead moved toward crowdsource testing of documentation, which proved to be more useful because it does not require volunteers to have professional writing skills, and it simplifies the tasks to complete as well as the time involved.

I think wikis could still be useful in some collaborative situations, but unless each of the collaborators truly has the ability to collaborate on the writing tasks, the wiki platform doesn't ultimately help the overall goal.

I do feel optimistic about crowdsouce documentation testing, but even this model needs to go a step further. Rather than having volunteers log into separate tools to test a task's accuracy, the pass/fail test should be integrated directly in each help topic and run on a continual basis. Each time a user reads and follows the help in a real situation, the user should be able to pass or fail the documentation -- based on his or her real-world need. If failed, a JIRA item should be automatically created for the writing team to address.

When the writing team resolves and closes out the JIRA item, the user receives a notification that the documentation has been updated. This notification helps the user know that reporting a failure helped improve the documentation. The user's effort was not unrecognized, and through his or her feedback, the documentation has become more usable for others.

The overall model is still collaborative, but the collaboration does not rely on end-users writing documentation.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.