Urban sprawl and car dependence -- some thoughts on solutions

- What is urban sprawl?

- The idea of a walkable city

- Solution #1: Switch from gas to EV cars in the suburbs

- Solution #2: Reduce parking in downtown areas to encourage public transportation

- The challenges of biking the last mile

- Multi-modal travel

What is urban sprawl?

Urban sprawl refers to the ever-growing expansion of single-family homes in residential neighborhoods farther and farther from cities. In these suburban areas, the primary means of travel is by private car. As a result, cars proliferate as the dominant mode of transportation, not just within the suburban areas, but into cities as well. The same people driving around in suburbs often drive their same cars into downtown cities. As a result, cars seem to dominate everywhere as the only mode of transportation. The car becomes the default way you get around.

Beyond congestion and car dependence, though, urban sprawl increases pollution and global warming, reduces the use of public transportation (busses run empty and have fewer stops due to lack of demand), reinforces racial divides through single-family-zoned housing (which eliminates less expensive multi-unit dwellings), encourages massive parking lots everywhere (creating the urban hell cementscape), increases pedestrian and bicyclist accidents/deaths (as well as de-incentivizes biking — no one wants to bike when their life is at risk), removes the greenery by destroying ecosystems (single-family homes are space inefficient and require parking garages), and more.

All of these problems are severe and worthy of discussion, but I want to focus on the transportation aspect. Urban sprawl promotes a car-dependent world. All those people like me who chose to buy a home in a residential area of a bedroom community are furthering the dependence on cars. Cars clog up streets and make it unsafe to walk or bike. They can convert what might be a walking paradise of downtown shops and livelihood to a dangerous urban hell with cars whizzing by everywhere.

The idea of a walkable city

One solution for avoiding a car-dependent world is to create walkable cities. A walkable city allows you to get to most things within 20 minutes (or allows you to easily hop on public transportation to go farther). More importantly, walkable cities make walking appealing to people. According to Project Drawdown:

Walkable trips are not simply those with a manageable distance from point A to point B, perhaps a 10- to 15-minute journey on foot. They have walk appeal, thanks to a density of fellow walkers, a mix of land and real estate uses, and key design elements that create compelling environments for people on foot. Infrastructure for walkability can include:

- density of homes, workplaces, and other spaces

- wide, well-lit, tree-lined sidewalks and walkways

- safe and direct pedestrian crossings

- connectivity with mass transit.

New York City is one of the best examples of walkable cities. You don’t need a car to get by in New York City; in fact, having a car is actually a liability in New York City (parking it is a huge, costly, time-consuming headache). Walking down Broadway in New York City is an appealing, visually stimulating activity, full of window shopping, people-watching, and landscape exploring. Places like New York City, San Francisco, Boston, Philadelphia, and Miami have high walkability scores, freeing those residents from a car-dependent lifestyle.

While the walkable city seems like a cool innovation, it’s problematic. The problem is that most desirable downtown options are unaffordable — for example, a two-bedroom apartment in downtown Seattle, with about 1,000 square feet, will cost ~$4K or more in rent. Homeownership would most likely involve a small condo only. The high costs make it so only dual-income professionals can afford to live there, and lower-salary workers are driven out.

Less expensive housing in downtown areas usually involves undesirable living conditions — renting a home that’s more than 120 years old and falling apart, for example, or living in a failing school zone, or living in a dangerous drug-infested neighborhood, or living right next to a freeway.

In contrast, housing options in the suburbs include two or three times as much space, much newer homes, yards, ample parking, and more greenery — in addition to costing much less. You can achieve the American dream with a house of your own, white picket fence, dog running in the grassy backyard, etc. The only tradeoff: you must drive a car everywhere. That’s the price you pay — being chained to your car. Urban sprawl dictates a car-only infrastructure. For most people, the car-dependent lifestyle is a price they’re willing to pay, especially with the trends toward working from home.

Solution #1: Switch from gas to EV cars in the suburbs

I support city designs and plans that encourage walkability without urban sprawl, and there are some good examples across the world. For example, downtown Brooklyn recently went car-free. For newer construction and future city development, that’s the way to go. But I’m skeptical that we can escape the urban sprawl infrastructure that we’ve built up nearly everywhere. Is anyone going to raze our suburbs into the ground and replace them with multi-unit dwellings connected to walkable transit hubs — probably not within any time frame that would avoid the “point-of-no-return” environmental disasters timelines that we frequently hear about due to the overuse of fossil fuels.

I mean, it takes years for cities to create a single new bike path or multi-use trail. For example, in South Seattle, there’s a project to create a new bike trail in Beacon Hill. Here are the timelines for the Beacon Hill bike route:

It takes three years of planning before construction even begins. In contrast, apparently we have about a seven-year window to avoid disastrous rises in temperature from global warming. ClimateClock.world says:

The next ~7 years is humanity’s best window to enact bold, transformational changes in our global economy to avoid raising global temperature above 1.5ºC, a point of no return that science tells us is likely to make the worst climate impacts inevitable.

The pace of development for more walkable/bikable cities (one new path in 3+ years) doesn’t match the urgency of action needed to combat climate devastation (~ 7 years). There’s no way to re-engineer the existing urban sprawl into walkable cities in a quick time frame. Urban sprawl exists and isn’t going away.

The practical solution, I think, is for those driving in suburbs to switch from combustible-engine cars to electric vehicles, also called EVs. (Or to adopt other cleaner energy vehicles.) EV-car dependence might not address the other harms from urban sprawl, but EVs could help address global warming/pollution issues. Granted, the batteries involve heavy metal strip mining, but it’s a better alternative than combustion engines.

Two challenges are slowing the switch to EVs: cost and charging infrastructure. An EV costs a third more than a similar gas-powered car, and charging stations are not available in enough places. Making EVs affordable will require the government to subsidize these vehicles as well as invest in charging infrastructure. Until EVs cost the same as combustion-engine cars and can be charged quickly at home and work, their adoption won’t take off. Right now, if you want to buy an EV, plan to pay about $10k more than for the same gas-powered car, and another $2k to add a charging station at your home.

I bought a car about four months ago, and I really wanted to get an EV, specifically a Chevy Bolt. But it would have cost about $25-30k even after the subsidies. Less expensive EVs like a used Nissan Leaf have low ranges (~ 70 miles). In the end, I just bought a 2013 Honda Accord because I wanted something inexpensive and reliable. It’s just hard to swallow the financial cost of an EV right now, but hopefully that will change as these cars become more affordable, their range increases, and more charging infrastructure becomes available.

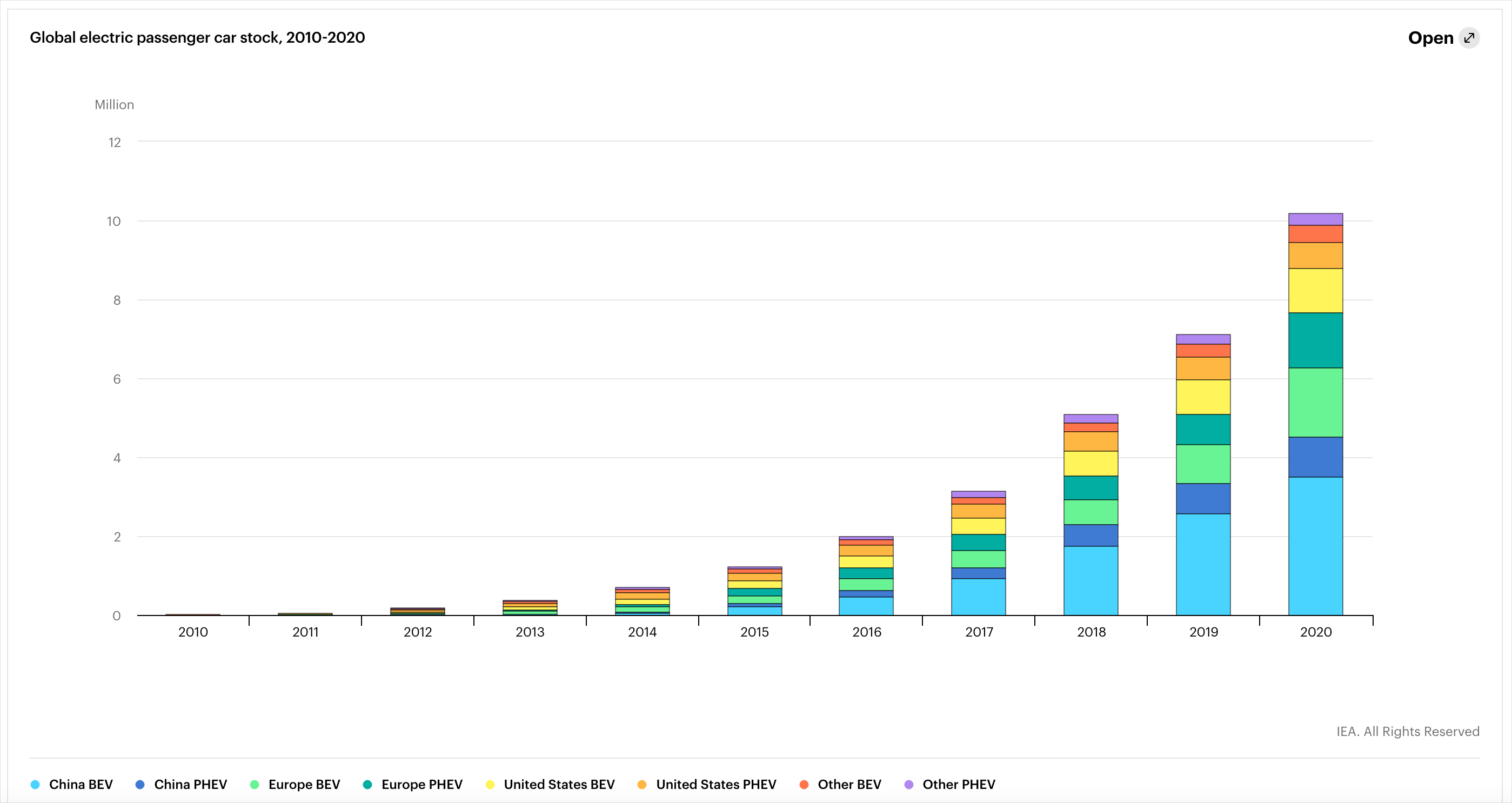

The success of Tesla is encouraging, especially with the recent Hertz announcement to buy 100,000 Tesla Model 3’s by the end of 2022. In many ways, Tesla’s success and popularity is driving other car manufacturers to follow suit with EVs. The adoption rate of EVs is on an exponential trajectory globally (more so in Europe and China than the US).

When I test drove an EV, I really liked the responsiveness — they’re zippy, quiet, and feel very modern. I can imagine a world where everyone drives EVs in suburban neighborhoods. And in fact, car dependence in suburbia isn’t so bad. These areas aren’t as congested as downtown cities at rush hour. Driving your car around (for example, taking your kid to soccer practice across town) is pretty convenient. Granted, this makes it so bicyclists and pedestrians are at risk, and there often aren’t safe routes for anything but cars. But this is the infrastructure we built, and if it’s the only practical solution, then we could at least reduce the pollution.

Solution #2: Reduce parking in downtown areas to encourage public transportation

EVs won’t reduce dependence on cars, but reducing parking in downtown areas will. If you eliminate parking, you de-incentivize driving. If we shut down even a third of the streets downtown or made them much narrower to accommodate wider, protected bike lanes (which might make driving slower than biking), it would encourage people to use public transportation (such as the Sounder train or Link Light Rail) and bikes in downtown areas. A typical commute from urban sprawl looks like this:

- Drive your EV to a transportation hub (e.g., train station).

- Ride the train into downtown.

- Use a bike, scooter, or walk the last mile to work.

Why eliminate parking as a way to reduce cars? While congestion pricing could de-incentivize driving, reducing parking availability has a similar effect without triggering driver hate or targeting class lines. Many downtown streets could be converted into roads closed to outside traffic (Stay Healthy Streets or greenways), allowing them to transform into safe cycling options. Bicyclists could then more easily get around the city and feel safe doing so.

I’m not saying all streets should be blocked off, but if we just created a good balance of bicyclist/pedestrian-only streets that could reach most parts of the city, it would do wonders to promote more bicycle riding. And unlike the timelines for creating new bike paths, it only takes a barricade and a sign to block off a street. It could literally be done on a shoestring budget overnight.

There’s already a lot of momentum for more bicycle-safe streets in Seattle. A new protected path just opened up along 4th Ave, and there’s also a 2021-2024 Bicycle Master Plan. A Vision Zero pledge is underway to reduce bike/pedestrian accidents to zero.

Until cities make it so that driving is less convenient, less comfortable, and less time-efficient than public transportation + bike/scooter options, the switch away from car dependence won’t happen. If it takes 45 minutes to drive and park, but 1.5 hrs to take public transportation (including sitting next to others or having to walk in the rain), cars are going to win that choice.

The challenges of biking the last mile

Another reason to block off more streets is that it will make biking more accessible to mainstream people, making it more of a feasible option, no matter one’s age or physical status. Currently, riding a bike in downtown Seattle requires a modest amount of preparation and skill that can be intimidating to non-cyclists. For example, you need to know the following:

- Which routes are safe (with protected bike lanes or closed streets) to get to your destination. Google Maps might not be the best map for figuring out bike paths. Instead, use a map like this interactive Seattle bike map.

- The high-risk situations to look out for, such as where cars might turn into you, doors that might open, parking garage exits, and so on. If you read this Seattle Dept of Transportation Bike and Pedestrian Safety Analysis, you’ll see that most accidents happen at intersections, with cars turning into bikes. As a result, I’m usually extra alert at each intersection and I scan obsessively. A two-way protected bike path means some cars turning might not naturally look for bikes in the direction they anticipate.

- How to deal with inclement weather, which means rain in Seattle, and the question of rain gear. (Hint: choose visible colors and be wary of promises about fabric breathability.) You also have to know how to ride in the rain (e.g., how to eliminate foggy, wet glasses), and how to anticipate reduced visibility from drivers. I never assume that drivers see me in their blind spot, especially in rain.

- How to transport your bike on your car, which might involve installing a hitch or trunk rack, loading it on, and strapping it down. With the supply chain crisis, it might take months before you can get a hitch installed. (It took Rack-n-Road three months for the parts to arrive for my hitch so they could install my Thule Helium Pro 3 rack).

- How to carry your gear in a pannier bag. (That extra pair of work shoes won’t fit, trust me.) You want to pack your bag as light as possible so you can easily lift it up and onto the train as well as carry it up stairs as needed. I love my Ortlieb Urban Downtown Commuter pannier. You also have to know to park and lock your bike at work, especially if your work doesn’t provide an inside cage. And also how to change at the office if your office doesn’t provide showers.

It’s not rocket science, but there are many people for whom biking might pose a lot of learning and familiarization before it could become an option. Think of someone who is completely new to all of this — just figuring out how to get started is a huge obstacle. To demonstrate, watch some videos from UpRide to see how cyclists have to frequently avoid turning cars or how they deal with other close calls

The closed streets would provide an easier on-ramp into the biking world for novice riders. When I look at video clips from bike routes in Holland and other areas of the world, I see people of all ages riding on bikes of all kinds. But it’s partly because the routes are dedicated to bicycles only and offer wide paths and easy routes. That kind of experience isn’t going to happen when bicyclists are limited to small shoulder lanes on the sides of traffic-congested streets where cars dominate. It doesn’t take but one close call with a car (whether unintentional or deliberate) to scare people away from biking.

For some examples of safe biking experiences in cities, see these videos:

Netherlands:

Denmark:

Notice how most of the people cycling look like normal people — young, old, and in various states of physical condition. More accessible, safe biking means more people can and will bike. In contrast, without safe, wide paths and an abundance of routes, the number of people who can successfully bike is far fewer and requires a high degree of expertise. If the only people who can navigate the car-dependent streets are bike messengers, then biking won’t get traction, and we’ll just see more cars, which in turn will make biking even less safe and encourage more driving.

Multi-modal travel

The most practical solution doesn’t involve only EVs or only bikes but rather a combination of the two. From your suburban neighborhood, you drive your EV with your bike mounted on the back to a nearby transit hub, such as a train going into the city. You park your EV at the transit hub and leave it all day. (BTW, the shorter range here — driving only to a transit hub rather than all the way into the city — also complements the limited range of EVs.) You take your bike with you onto the train. When you get off at a downtown station, you bike or ride a scooter (or walk) the last mile to work. It’s that simple. This is what I described in my post Biking and public transportation: Solving the first- and last-mile problems.

Find the combination of driving, public transportation, and biking/walking that works for you in your commuting needs. (Or if you can avoid the commute altogether and work from home, great.) I’ve emphasized bikes here, but you could also get by on scooter shares, which seem popular. (However, scooter shares seem costly and impractical in the long run to me.)

A multi-modal solution is practical, feasible, and works quite well. You can recoup not only some work time on the train, you also won’t have the mental exhaustion of driving in rush-hour traffic. And with the right protected path bike lanes downtown, you won’t be on edge as you ride. In fact, the ride might actually be enjoyable. You get some exercise, fresh air, and you have greater freedom and flexibility. You’re not trapped in a steel cage but are using your body and are outside.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.