Stoplight -- creating a single source of truth to drive the API lifecycle

- Limits to line-by-line spec coding

- Not just simpler tools, but a design-first philosophy

- Not a post-design artifact to generate documentation

- Documentation hosting features on Stoplight

Note that Stoplight is one of the sponsors of my site.

Limits to line-by-line spec coding

At the recent TC Camp unconference here in Santa Clara, the camp organizers put on a full-day API workshop focused on OpenAPI and Swagger. I was excited to see this topic addressed in a workshop because I think coding the OpenAPI spec is both the most complicated and most important part of API documentation.

I didn’t attend the workshop myself, but I was chatting with a few who did. One attendee was a little frustrated that they spent so much time in YAML working on different parts of the OpenAPI spec definition. He said they actually spent most of the day in YAML, and it was kind of frustrating/tedious/boring. For this participant, this isn’t what he imagined when he signed up to learn how to create interactive API docs.

In the instructor’s defense, I told my friend that describing an API using the OpenAPI spec does pretty much involve living in YAML all day, and it is tedious, highly prone to error, and technical. One of my favorite API bloggers, API evangelist Kin Lane, explains that “hand crafting even the base API definition for any API is time consuming.” It is an activity “that swells quickly to being hours when you consider the finish work that’s required” (Automated Mapping Of The API Universe…).

Lane says he was exploring ways to automate the API definition using different tools such as Charles Proxy. During this time, he started exploring Stoplight.io, a platform for modeling APIs and more, and he became engrossed in the workflow and design tools. He says,

I stayed up way too late playing with some of the new features in Stoplight.io. If you aren’t familiar with what the Stoplight team has been cooking up–they have been hard at work crafting a pretty slick set of API modeling tools. I feel the platform provides me with a new way to look at the API life cycle–a perspective that spans multiple dimensions, including design, definition, virtualization, documentation, testing, discovery, orchestration, and client. … I am curious to see what API designers, and architects do with Stoplight–I feel like it has the potential to shift the landscape pretty significantly, something I haven’t seen any API service provider do in a while. (Automagically Defining Your API Infrastructure As You Work Using Stoplight.io)

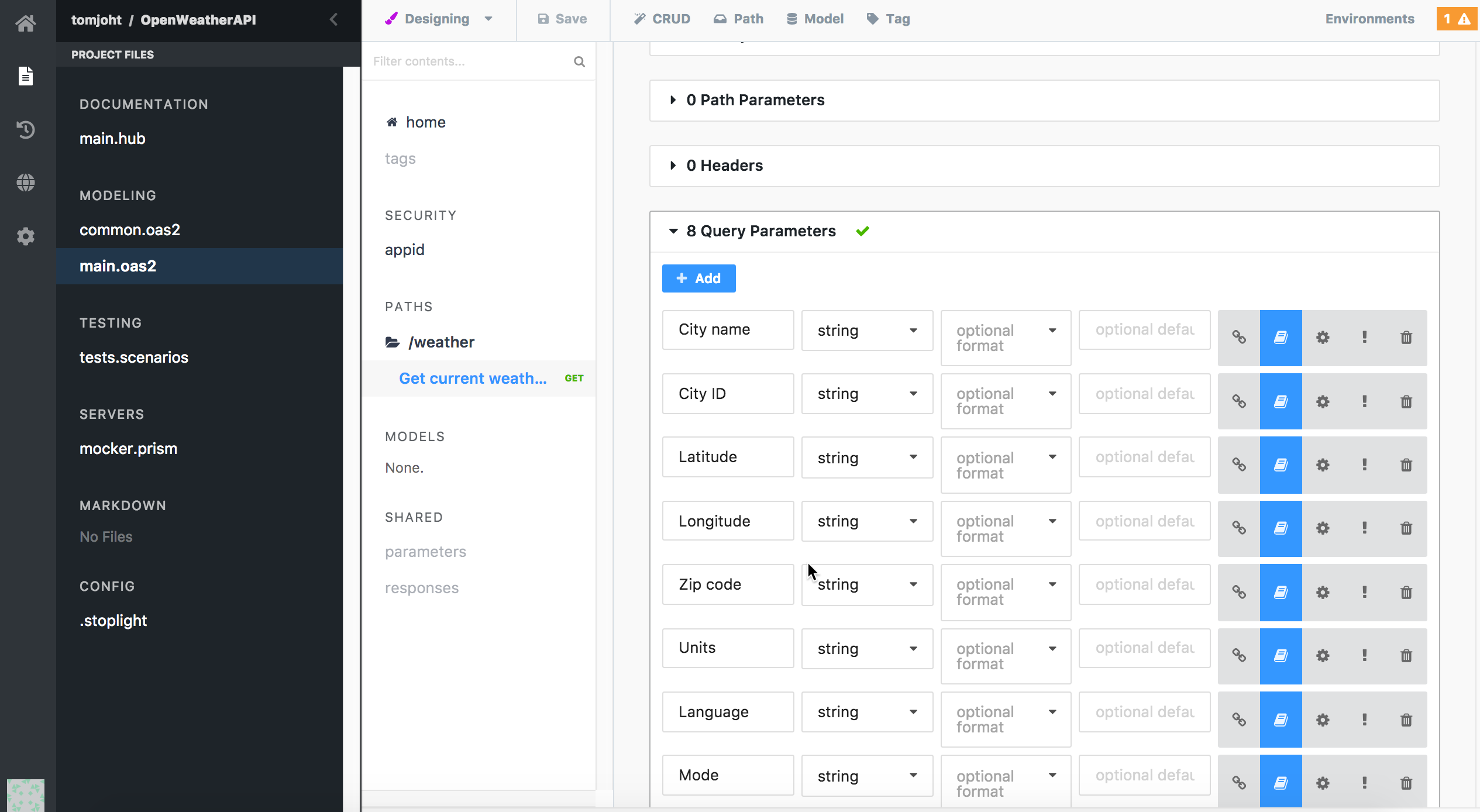

I, too, started playing around with Stoplight. I was curious to see whether the visual modeling tools for describing an API could take the tedium out of working in YAML on a line-by-line level with the spec. While using Stoplight to create an OpenAPI description for a recent (still unreleased) API at my work, and I found Stoplight to be really useful. It made it much easier to create the OpenAPI description.

Stoplight’s visual modeling tools eliminate the need to be familiar with the format of the specification. You don’t have to know the data type for each property, whether the property needs to be indented or defined directly and so forth. That level of complexity has been abstracted away in a GUI for designing your API.

As part of the visual modeling tools, Stoplight’s interface for describing JSON schemas (used in request bodies or responses) is especially welcome. Details about how to document JSON schemas aren’t fully documented in the OpenAPI spec, so they can be particularly challenging. What’s especially neat is that you can simply paste in a chunk of JSON and Stoplight will automatically describe it in the right syntax for you. You do this using the Generate from JSON button, as I’ve demonstrated in this short video:

Additionally, you can toggle between the visual tools and the specification code easily. If you want to work in the code, your updates will update the UI as well. The two sync perfectly when you make updates in either mode. Here’s a short video I made showing this:

Not just simpler tools, but a design-first philosophy

After playing around with Stoplight, I had the opportunity to chat with Marc Macleod, founder of Stoplight, about how Stoplight differs from SwaggerHub and Readme. Marc said when the spec was first introduced, he saw value in having a standard specification for APIs, but at the time, all the tooling required users to write the specification line by line. This hand coding was error prone, slow, and tedious.

Marc and his team designed Stoplight with visual modeling tools that don’t require teams to know the details of the OpenAPI spec. This simplification of tooling opens up the spec’s development to a wider number of team players — to product managers, developers, UX designers, technical writers, and more. The barrier to entry in the design and prototyping of the API grows beyond the scope of just engineers.

Building the specification document is probably the most important activity in API development, because once you have this API description, you have a single source of truth. This single source of truth can then inform and empower a variety of other roles: developers, testers, user experience designers, technical writers, sales, and more. Marc’s core philosophy is that the OpenAPI specification document is central to API development. Once you have this specification document, you can build tools around it to empower these other teams. For example, after you have the specification document:

- UX designers can prototype the API using a mock server to let users execute requests and see sample responses — before developers even write one line of code.

- Developers can write code by following a specific contract, like a construction team following a blueprint. All the decisions and questions have been put into the specification document to make it actionable.

- QA can automate unit testing from the API description to speed up endpoint testing across a variety of parameters and scenarios.

- Technical writers can add descriptions and other examples to the specification description, and then generate interactive documentation without worrying about developing their own templates, styles, or other formatting and organization.

If the OpenAPI specification really powers all of these other activities, doesn’t it make sense to build your platform around the specification? And from a larger view, to build your business around the specification? That’s what Stoplight is doing. It’s what makes them fundamentally different from other API platforms. I think it’s what Kin Lane meant when he said Stoplight provides “new way to look at the API life cycle–a perspective that spans multiple dimensions, including design, definition, virtualization, documentation, testing, discovery, orchestration, and client.”

Not a post-design artifact to generate documentation

The OpenAPI specification isn’t just an artifact that describes what the developers already coded. Nor is it just a way to create interactive docs featuring a built-in API explorer, or even to make your API machine readable for larger systems to consume. The OpenAPI specification is a way to design and model your API. Given this purpose, the tools for designing and modeling your API need to be more flexible, easier to manipulate and maneuver by designers and product managers.

Consider this analogy. When I write blog posts, I often write in an editor like Bear or Ulysses or Google Docs, because these tools make it easy to express myself. I can edit and move content around, or insert notes and half-formed thoughts. Only after I’ve finished the content do I move it into Markdown or HTML and then populate the structured YAML in my post’s frontmatter. It’s the same with the API specification. When you’re designing and modeling your API, you don’t want to be worrying about whether your YAML syntax is valid, or be constantly consulting the reference documentation to remember what properties are required or not required at each level of the schema.

If we’re ever going to embrace modeling and designing APIs in a collaborative way, we can’t do it using a YAML editor writing in the spec’s rigid syntax. If we don’t have tools to design and model collaboratively, the spec gets designed and developed elsewhere (such as in the pages of Confluence, or in a Word document on a product manager’s computer). The specification document becomes an afterthought to design, something that a techie (such as a developer or technical writer) comes along later to create post-development.

This has, unfortunately, been the approach in 100% of the APIs I’ve worked on — I create the spec after the API has already been designed and coded. The spec becomes just a way to generate reference documentation for the existing API, rather than as a single source of truth that empowers the whole API lifecycle from beginning to end. Invariably, as soon as user testing begins, the project team discovers shortcomings in the API’s design they don’t have time to fix.

This practice of putting the spec last (rather than first) in the API’s development limits the scope of what the OpenAPI specification can do. Lane explains:

Many developers still see OpenAPI (fka Swagger) about generating API documentation, not as the central contract that is used across every stop along the API life cycle. Most do not understand that you can mock instead of deploying, and even provide mock data, errors, and other scenarios, allowing you to prototype applications on top of API designs. (Code Generation Of OpenAPI (fka Swagger) Still The Prevailing Approach)

To counter poor practices with spec-last development, Lane says more and more platforms are pushing code development further down in the API lifecycle. In other words, design and testing are done first, code development done later.

As I was explaining the idea of spec-first development to our product manager and other leaders, they suddenly became very intrigued. I explained that we can use the OpenAPI specification to do prototype design and UX testing of the API before we even think about development.

The product managers found this idea compelling no doubt because some previous attempts at creating an API weren’t so successful. In fact, we were discussing plans for an API to replace the previous API that never caught on because the intended developer audience found it too clunky, cumbersome, and off-target with the information they needed. It was a failed API.

The light bulb was going off in these product managers’ heads. They started to recognize a way to avoid a similar failure scenario. By pushing code development later on in the API lifecycle, we could avoid scenarios where we lose months of work due to unforeseen requirements or other poor planning. Through the API definition, we could build a nearly functional prototype of the API before code development, including mock servers to simulate actual responses that users could evaluate and provide feedback about.

In this design-first model, technical writers can also insert themselves early in on the API design process, providing input about the shape and model of the API at a time when their input might actually get traction. Once the API gets coded by developers, it’s extremely hard to change even something as simple as the casing of a parameter name, much less the parameter itself.

Documentation hosting features on Stoplight

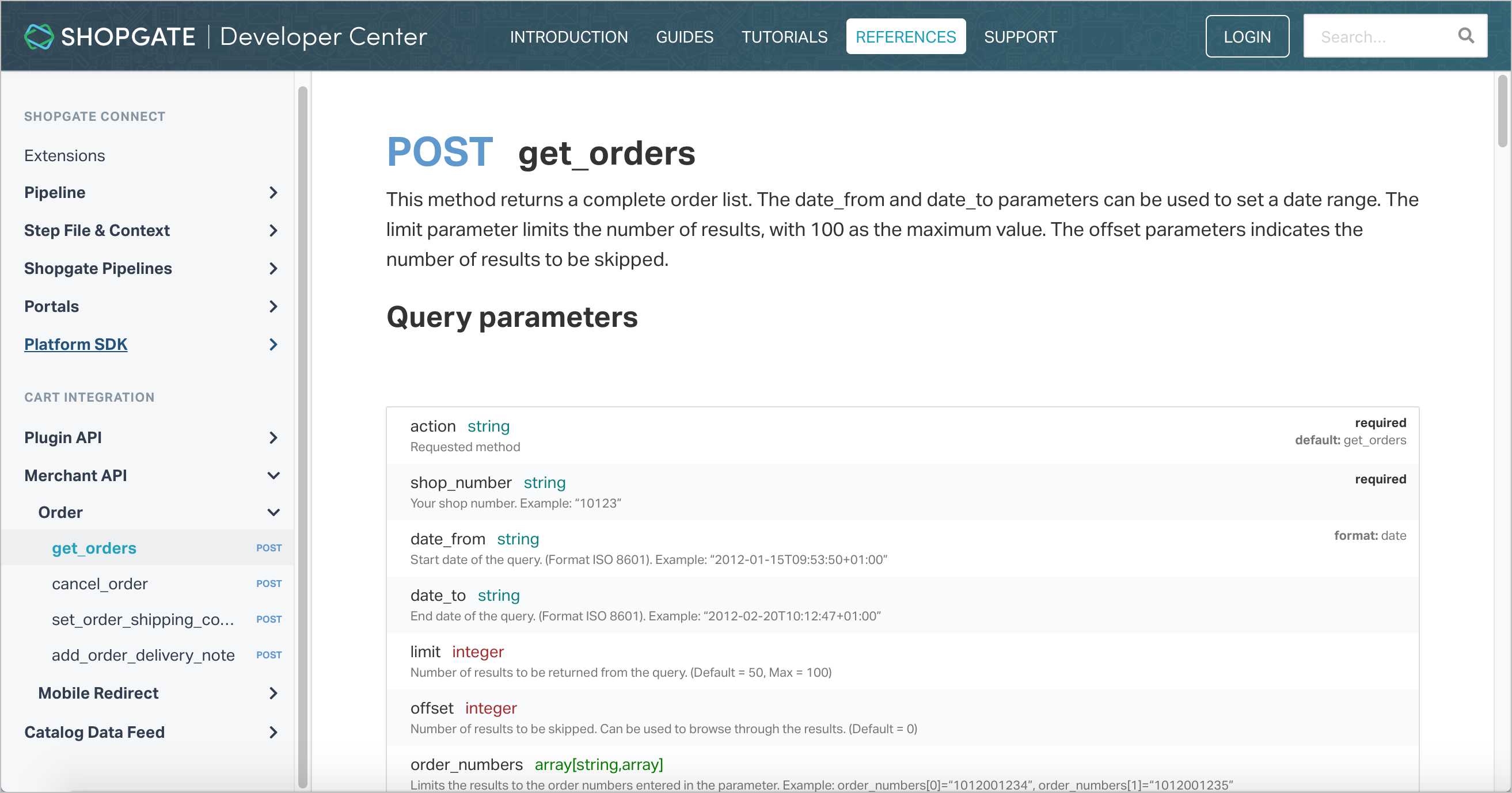

In addition to putting the OpenAPI specification at the center of the API lifecycle process, Stoplight has some other features of particular interest to technical writers. Stoplight offers a hosted docs solution, where you can integrate your non-reference content (the tutorials, guides, and other how-to’s) together with the reference API docs. Here’s an example hosted doc site on Stoplight for a product called Shopgate.

Stoplight also allows you to create variables to use in both your specification and your how-to docs. Stoplight plans to take re-use one step further by allowing re-use of your spec’s component definitions in your non-reference documentation as well. (But this feature is still forthcoming.)

Although I generally like working directly in the code, I’ve found that Stoplight lets me focus more on the content and less on the details of the spec’s format. Ideally, you can probably get developers and other project team members to populate reference content in Stoplight themselves, since this is an activity that needs to happen much earlier in the API design process anyway.

If you’re documenting an API, Stoplight (and their hosted doc solution) are definitely worth checking out. But don’t think of Stoplight as just a documentation platform or an easy way to generate the OpenAPI description. Consider Stoplight a way to design the single source of truth that will empower all other teams in a more efficient toward a successful API.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.