Review of Parmy Olson's Supremacy — and the futility of chasing non-capitalist dreams

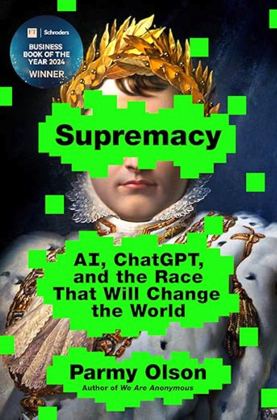

Parmy Olson’s Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World describes the pursuit of AGI as a race between two visionary AI entrepreneurs, Sam Altman (OpenAI) and Demis Hassabis (DeepMind), both of whom initially wanted to change the world for the better with AI. Altman envisioned using AGI to unlock abundance for humanity, while Hassabis, more of an introspective scientist and gamer, hoped to solve humanity’s greatest challenges, like curing disease or solving impossible physics problems.

However, they ultimately struck what Olson calls a “Faustian bargain,” selling out to big tech to fund their immense infrastructure and compute needs. OpenAI pivoted from a non-profit to accept a $13 billion investment from Microsoft, and DeepMind was acquired by Google for $650 million. The sellouts derailed their initial altruistic goals, pulling them into the “vortex” of big tech where their labs became strategic assets for corporate partners optimizing for growth and profit. In a classic tragedy, Olson shows how their initial ambitions for societal advancement, abundance, scientific revolution, etc., were rerouted toward corporate agendas instead.

The sellout is a familiar theme to many tech writers working in the industry. In the case of the tech writer, rather than selling out society, many writer-oriented college grads sell their personal lives to companies to earn livable salaries. After my MFA in creative nonfiction, I thought I’d write a book or write magazine articles or even teach, but those ideas didn’t pan out. Except for a few writers on top, writing doesn’t pay enough, and teaching (which also pays poorly) isn’t my strength. I wended my way towards tech writing and found that it pays surprisingly well. In fact, writing API docs for big tech companies pays exceptionally well.

But there’s the sellout problem. One might think that after putting in a full day’s work writing docs, you could spare several hours at night or in the early morning to write that creative novel, or pursue some other larger pursuit. You can do it, sort of. It’s a tough road to follow. When I read books like Olson’s, it’s clear she immersed herself in research, especially journalistic-based research, for multiple years. I doubt it’s something one can pull off as a side gig, in the same way it’s unlikely that Demis Hassabis will unlock the mysteries of the universe in off hours at night after finishing work for his day job at DeepMind. (But one can hope.)

The scale of these sellouts also differs. A creative writer who becomes a professional technical writer makes a personal trade-off, exhausting his or her creative energy crafting documentation for an API instead of writing the next Moby Dick. This is different from an AI entrepreneur whose grander ambitions—using AI for medical breakthroughs, scientific discoveries, or societal abundance—are compromised. The loss of a potential novel is more of a personal one; the loss of a potential cure for cancer affects larger swaths of society. (BTW, this distinction elevates the AI researcher to a more godlike role, where he or she is on the verge of massively transformative changes that promise to remake society—a goal that many think overestimates and falsely aggrandizes their capability.)

But even with this difference, I like exploring the sellout theme. There are dozens of other themes to comment on in the book, but in this post, I’m focusing only on the sellout angle. Sadly, the further we dive into this topic, the more depressing it gets. Olson’s book portrays big tech companies as the ones squelching out the AI entrepreneur’s dreams. If only OpenAPI could keep its focus on unlocking abundance instead of unlocking profit, think how lifechanging those results could be! one might say.

In reality, the CEOs of tech companies are beholden to shareholders who demand profit increases. For tech companies, those quarterly profits have to follow hockey-stick trajectories. Most tech companies also sold their souls when they turned from private to public with an IPO, a decision they made to scale and grow on another level. Even if a company isn’t public, they’re funding their infrastructure and compute needs through investors and venture capitalists who expect a return on the millions/billions they’re pouring into the company. Consider the ROI demands that OpenAPI is already facing, given the billions that investors are providing. The scope of the investor money directly relates to the scale of the company’s future promises.

But where does this relentless pressure for profit come from? It’s easy to blame faceless shareholders, but the chain of responsibility runs deeper, often starting with everyday people. Retirees, families, and individuals invest their savings in funds managed by professionals. These fund managers, in turn, have a duty to grow those savings to help their clients keep pace with the rising costs of housing, education, and healthcare. To get those returns, they invest in the stock market, becoming the powerful shareholders that pressure CEOs to deliver ever-increasing profits. In this way, a family’s need to fund a retirement account translates directly into the pressure a company feels to prioritize profit, creating a systemic demand that travels all the way up to the boardroom.

Is the capitalist economic model of society to blame, then? The alternative of a state-controlled, totalitarian regime like North Korea or China making decisions doesn’t seem like a good alternative either.

With capitalism in place, are we locked into a trajectory that’s designed to squelch out the dreamer in favor of more profit-driven activities? Whether you start out thinking you’ll write a novel, solve Alzheimer’s, or build AI that reverses climate change, at some point those ambitions get derailed in favor of the need for profit and capital. We end up with compromised ambitions, working for a system designed to maximize profit because we need similar profit to survive.

This is a depressing take on society, one where there’s little hope except to try to find meaning within a profit-driven role and activity. I’ve tried that through this blog over the years, writing creatively about technical writing. It’s the compromise I’ve made between my more creative ambitions and the need to devote and tailor my activities around ones that return a profit and help sustain me financially.

This feeling of being trapped in a system with its own inscrutable logic isn’t new. Think of Franz Kafka, who spent his days working as a lawyer for an insurance company while devoting his nights to writing. His masterpieces, The Trial and The Castle, are explorations of individuals crushed by vast, impersonal, and absurd bureaucracies. Kafka didn’t just write about these themes; he lived them, channeling the anxieties of his corporate job into his art. He is perhaps the ultimate archetype of the modern struggle to find personal meaning while serving a larger, indifferent system. In this sense, then, rather than seeing the capitalist system as antithetical to our more altruistic pursuits, perhaps the struggles can ignite and catalyze more creative expressions? Could Kafka have written what he did if he hadn’t been working for an insurance company? What would my blog be like if I weren’t working for a tech company?

One idea Olson doesn’t explore is whether both agendas can be achieved working within the capitalist framework: both the altruistic agendas and the profit agendas. Or to frame it more personally, can you have a fulfilling life working in a capitalist role where most of your energies are focused on making profit? Can you still achieve some personal meaning while serving a larger, indifferent system? I think the answer has to be maybe or yes. When people retire and stop working, they often report boredom and loss of meaning, no matter if they disliked their jobs. The same is often said of parents burdened by demands to care for their children. Once they become empty nesters, they seem to lose a lot of purpose and meaning.

Perhaps the key, then, is to embrace the stress of whatever situation you find yourself in, recognizing that it provides the conflict and substance that often fuels creative or meaningful work. This might be more true for writing than AI research, and it might be a perspective I’ve settled on instead of accepting the sellout as a final verdict. Even so, I think there’s an argument to be made for working within whatever system you find yourself in, especially if there’s no compelling alternative.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.