The cost of speaking up: Thoughts on "The War on Words" by Greg Lukianoff and Nadine Strossen

- Overview of the book

- Arguments in the book

- Living in a democracy is tough

- It’s difficult to speak truthfully without incurring animosity

- Strategies for more tactful disagreement

Overview of the book

War on Words is structured as 10 separate arguments in which both writers present their take on an issue. Nadine Strossen, a liberal former ACLU president, and Greg Lukianoff, a specialized free speech advocate, take turns arguing their positions on a variety of free speech issues, such as whether words equate to violence, or whether shoutdowns are a form of free speech. It’s a short but substantial read covering everything from legal history to social psychology.

Because both authors share roughly the same position (rather than debating opposing sides), this alternating format prevents the book from developing a cohesive, centralized argument. It felt a bit disjointed, likely because the authors approach the same topic from different disciplines—Strossen offers legal analysis while Lukianoff focuses on cultural arguments—without weaving them into a single narrative. In fact, it reads like two experts deciding to each write 10 blog posts on a series of topics, and then compile them together into a “book” (which, according to the acknowledgments, is exactly how this project started). It’s a format I probably wouldn’t tolerate at length, but for 82 pages, the brevity allowed me to get through it. It’s not intimidating to assign as reading material in a book club, and it could also work well as reading material in a high school English or debate class.

Despite my misgivings about the format and length, the book opened my eyes to how interesting the topic of free speech is. Not only have free speech issues occupied the national attention for the past several years, free speech issues also date back to Socrates, who was put to death for corrupting the youth.

To see the prevalence of free speech issues, just survey the news of the past several years: the cancel culture on college campuses, controversies about Israeli-Palestinian positions and “river-to-sea” chants, Trump’s January 6 speech and subsequent mob attack on the Capitol, the murder of Charlie Kirk and censorship following his death for various responses, the firing and reinstating of Jimmy Kimmel, and so on. Especially as Trump curbs press access, removes inspectors general, reduces broadcast funding or licensing, and more, free speech has emerged as a dominant issue, maybe even the dominant issue during the Trump era. Many people outside the US are wondering why Americans don’t speak up and protest more.

But beyond the national events, I’m also intrigued by free speech on a personal level. As a blogger who frequently writes what he thinks about trends, tools, practices, or events, I want a better handle on what’s permissible, where I might be crossing the line, and just what the law is. This book got me thinking about these issues. The book also primed us for a great book club discussion at the Big Time Brewery & Alehouse, where I sat with about a dozen other adults and discussed complex issues related to free speech (before following another interesting topic late into the evening).

Coincidentally, the morning after our book club meeting, Greg Lukianoff appeared on a New York Times Daily podcast (Dec 6, The Lonely Work of a Free-Speech Defender), which was a more interesting conversation than I anticipated. In the podcast, Lukianoff revealed that he went through some dark times in his past, even contemplating suicide. During that time, he discovered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and figuratively “gave free speech” to his own internal struggles. In other words, he didn’t suppress the free expression of those dark thoughts but invited them into the open. This allowed him to inspect and analyze the issues almost objectively and, in so doing, depower them.

In the podcast, Lukianoff also mentioned that he can’t stand going to sporting events because the crowd’s cheering and chanting in unison deeply unsettles him. He attributes this to his heritage/upbringing. He grew up in Connecticut, but he was raised by a Russian father who valued “brutal honesty,” and Lukianoff believes he carries an inherited instinct to flee totalitarianism. (If you don’t read the book, definitely listen to the podcast.)

Arguments in the book

Lukianoff and Strossen’s central arguments are that speech should be allowed except in very narrow “emergency” circumstances, such as when speech causes direct, imminent, and serious harm (not just making someone feel uncomfortable or offended). This includes things like actual threats, incitement to immediate violence, or targeted harassment.

Strossen clarifies that the government can also punish speech crimes like defamation, fraud, and perjury, where false factual statements cause specific damage to reputation or property.

However, they argue we should strictly protect offensive speech, “hate speech,” and general misinformation. Their reasoning goes beyond the standard “marketplace of ideas” (referring to the idea that the truth will win out on its own when pitted against competing claims). Greg Lukianoff proposes a more compelling theory called “The Lab in the Looking Glass.” Basically, this refers to a scientific lab that consists only of a mirror, showing the researcher an image of him or herself.

With this analogy, Lukianoff argues that even if an idea is false or hateful, it’s scientifically valuable to know that people believe it. Lukianoff says we can’t understand the world as it actually is if we silence the voices we dislike. We need free speech not just to find the truth, but to know who our neighbors really are and what they’re thinking, even if the ideas are ugly. (To cite a recent event, think about how the president recently called the Somali people “garbage.” I think putting that comment out in the open rather than suppressing it with censorship reveals more about the president and ourselves based on our reaction.)

According to the authors, this open environment with protected freedom of speech leads to many beneficial outcomes, such as:

- Scientific discovery: The authors cite the “Lab Leak” theory of COVID-19, which was initially suppressed as misinformation but later recognized as a plausible hypothesis.

- Safety: Industries like aviation became safer when adopting an acceptance of dissent, such as allowing co-pilots to question captains.

- Fewer chances that a harmful belief will take root underground: Driving hate speech underground often radicalizes the speakers further.

- The ability to negate/neuter the ideas with counterspeech: The remedy for bad speech is often more speech in the form of counter-arguments.

The most compelling arguments appear in the last section, when we learn that prior to WWII, antisemitic speech was restricted in Germany and leaders like Julius Streicher were imprisoned over it, but this only fueled the Nazis’ sense of martyrdom. Meanwhile, Hitler wrote his manifesto, Mein Kampf, during an eight-month stint in prison, though he was there for high treason following a violent coup attempt (the Beer Hall Putsch), not for his speech. The authors argue this proves the government failed because it was too focused on censoring words while being lenient on actual violence.

Lukianoff and Strossen’s arguments reminded me of Jonathan Rauch’s The Constitution of Knowledge (a book I reviewed here). Rauch argues that our democracy’s strength comes from multiple institutions openly competing with each other in debates (from peer-reviewed journals to government institutions and more). When you’re silent, bad ideas are more likely to go unchecked. This is the foundation of democracy—the idea that free speech, especially open, allowed debate, leads to better truths and decisions.

Conversely, when a totalitarian government decides what’s right and wrong in each case, that is, when just one person or group makes all the decisions, the outcomes are more likely to veer from truth and what’s best for people. In those situations, the outcome is often tilted in favor of what’s best for the governing power.

Living in a democracy is tough

Lukianoff and Strossen say that living in a democracy is “tough” because it requires its citizens to speak up, even when it’s uncomfortable. Lukianoff writes:

“Being a citizen in a democratic republic is supposed to be challenging; it’s supposed to ask something of its citizens. It requires a certain minimal toughness—and commitment to self-governing—to become informed about difficult issues and to argue, organize, and vote accordingly.” (8).

Lukianoff contrasts this toughness of democratic systems with authoritarianism, noting that authoritarianism doesn’t ask its citizens to make any decisions at all: “The only model that asks nothing of its citizens in terms of learning, autonomy, and decision-making is the authoritarian one” (8).

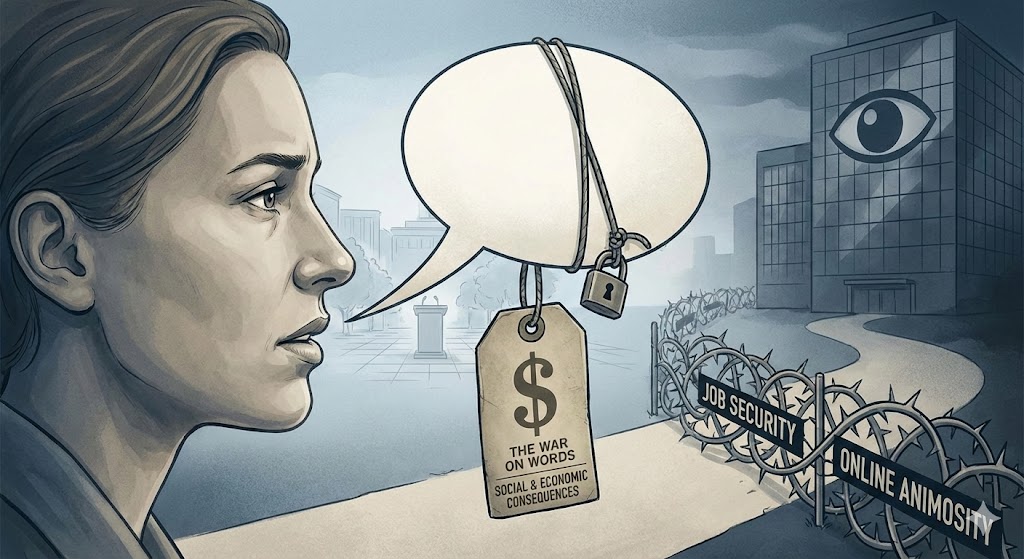

Here I have to admit that, as much as I agree about speaking up in principle, it’s hard to live up to this ideal. Even if you’re legally allowed to say something, there can be economic and social consequences for doing so. Many employees have been fired for speaking up about political issues and ethical concerns, both related and unrelated to their companies.

Lukianoff and Strossen argue that it’s in the best interests of companies to know what their employees think, to avoid emperors-new-clothes scenarios where everyone just goes along with an idea because the CEO says so. They warn against corporate cancel culture, arguing that firing employees for their opinions blinds the company to reality. But I found myself wondering whether the risks outweigh the rewards in these scenarios, in this economic climate. Are you going to come right out and make strong political/cultural opinions that might jeopardize your relationships with co-workers, risking unemployment just to maintain integrity for democratic principles? The person who speaks up might even be wrong or misguided.

During our book club discussion on this topic, one member recounted an experience during the pandemic in which one of his employees wore a face mask that said “Abolish the police.” Given that many of the customers were from police families, the person asked the employee not to wear the mask (thus, restricting free expression of speech) because allowing it would likely threaten the company’s business model. This experience highlighted the multi-faceted aspects of free speech between both employers and employees. (Interestingly, a similar scenario played out in federal court in Frith v. Whole Foods related to political slogans (Black Lives Matter) on masks.)

Standing up for your political beliefs is commendable, but the risks of doing so are more serious than before. Now, the lines are blurring between politics and companies. Previously, you could be politically active one way or another and it didn’t seem to affect your company employment much. But now the politicians in power are increasingly weaponizing the regulatory state to pressure companies to align with their political views.

For example, the Trump administration has suspended security clearances for law firms that represent political opponents (e.g., Perkins Coie LLP, Covington & Burling LLP), used merger approvals as leverage to ensure favorable media coverage (e.g., Paramount and Kimmel, Verizon and Frontier), stripped universities of federal funding and research grants if they don’t capitulate (e.g., Harvard, Columbia, Cornell), required companies to eliminate their DEI programs to secure contracts, and more.

If these institutions want to survive economically, they’re coerced into falling in line with political pressures. This also means companies might pressure employees to fall in line as well. As a result, you can lose your job by posting the wrong thoughts on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the Charlie Kirk murder on your independent, non-company-related blog or social media account.

It’s difficult to speak truthfully without incurring animosity

Beyond the economic pressures, it’s also hard to speak truthfully without incurring animosity. On my blog, I learned early on the consequences of free speech. During my early blogging years, I decided to adopt a writing experiment of picking a blog post someone had written and analyzing it. One of the first posts I picked turned out to be a landmine.

In my analysis, I both praised and criticized some of the blogger’s views, but in the blogger’s mind, these criticisms came across as damaging and spiteful. The author petitioned me to remove my post, which I did. It was never my intent to offend or upset anyone over topics within tech comm, and I didn’t want to continue this experiment of openly analyzing other bloggers’ opinions and arguments (even if I agreed with much of what they said). It just wasn’t worth it emotionally, and had little payoff except to increase my number of enemies online.

Since that time, I’ve embraced an “if you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all” attitude towards articles/posts I read online by other tech writers. I might read something and disagree with it, but I’m probably not going to devote a blog post trying to debunk or undercut the idea (or tool, company, or practice). The one exception might be DITA. (Just kidding.)

I realize this sounds spineless and undemocratic, and reading Lukianoff and Strossen’s book, I should have probably resolved to speak my open mind with a full analysis (both good and bad) of any idea, be it another tech writer’s post, company-related products or directions, and even national/political events. But the reality is that my life is too comfortable to give all that up, for so little in return.

Even on a more personal level, I often find myself holding back my thoughts to avoid conflict. Few things are as dangerous as sharing an honest opinion with someone who might not welcome it. Be prepared for a huge emotional battle followed by relationship strain and other negative outcomes. Is it worth it? Not usually, in my experience.

Strategies for more tactful disagreement

Perhaps there’s a way to disagree without leading to the headbutting and negative all-around outcomes that I’ve experienced in the past. During our book club discussion in the alehouse, a high school English/history teacher shared that she’d recently read a book called Crucial Conversations, and the takeaway in this context is that it provided some strategies for disagreeing with others without leading to offense and arguments. She noted that the authors advise starting any disagreement by analyzing intent. If you can understand the other person’s intent, you can usually establish some common ground.

Perhaps the first step in confidently moving towards more open speech, then, is to embrace this strategy: understand another person’s intent. This requires both listening and empathy. One of my weaknesses is that I’m too often a peacemaker, ready to switch away from difficult/explosive conversation topics and smooth over rough emotions rather than ripping off the Band-Aid. I dislike it when others are upset, as I’m empathically wired to internalize their emotions.

But maybe if I started down the road of intent, it would help me build up enough of a relationship where the other person wouldn’t receive my criticism with a furrowed brow but rather in more of a spirit of productive inquiry. That inquiry and trajectory is certainly a path worth traveling down, even if it’s a bit rocky.

Trying to understand another person’s intent, listening to their perspective and trying to unpack their emotions and logic, requires a tremendous emotional intelligence and so much calm-minded inquiry that it’s almost superhuman. In the heat of dispute, it’s hard to move out of the moment and into a more objective analysis of the situation. Instead of speaking up in the moment, it’s probably better to wait a week or two. Building on intent and fully listening to others is something I’m still working on, but it does seem like a necessary strategy to embracing more open speech.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.