Bakhtin and model collapse: How to use AI with expressive writing without generating AI slop

- Introduction

- Writing categories: expressive vs encyclopedic

- Heteroglossia

- Deep dive into heteroglossia

- From Bakhtin’s heteroglossia to AI model collapse

- Takeaways and a new approach to using AI with expressive writing

- Conclusion

- Works cited

- Related resources

Introduction

It seems like every time someone talks about AI and writing, it’s usually to slam AI slop and to say how much of a turnoff AI writing is. I agree that AI slop is terrible to read. It’s generic, void of unique voice, lacks first-person perspective and experience, and doesn’t say much at all. I also dislike reading it.

The problem, though, is that assuming all AI-assisted writing results in AI slop seems dismissive of the potential of AI. Is it possible to somehow use AI with more creative genres of writing in a way that doesn’t result in slop? In this post, I’ll explore ways to use AI to level up the quality of expressive writing without resulting in garbage output, and without robbing writers of the value of the writing process itself.

In brief, I argue that writers can use AI as a research assistant to add additional voices and perspectives into their writing; this contribution adds a heteroglossic quality that actually brings the content to life and deepens its meaning. AI can also be used to properly verify that you’re engaging with the authors in your essay fairly, representing their views correctly. In this post, I dive deeply into Bakhtin for my critical lens.

Writing categories: expressive vs encyclopedic

First, let’s acknowledge that “writing” is such a broad category that applying blanket statements about AI and writing without qualifying what type of writing we’re talking about is generally misguided. This is a problem I encountered in Jonathan Warner’s More Than Words, which is otherwise an excellent book. Had Warner clarified the type of writing he was analyzing in the context of AI, it would have been easier for me to support his arguments.

In the corporate enterprise, a lot of writing happens, but very little of it is expressive. Few people care how AI-assisted the enterprise content is, as long as it’s accurate and clear. For example, take technical documentation for APIs. In this genre, you’re describing an API field, writing code, code comments, or internal procedures. By and large, when you have a scenario that’s highly technical and impersonal, with no expectations about arguments and perspectives, AI does a good job at the writing without slipping into soulless superlatives and flowery sentences.

In fact, in many cases, AI can help improve the accuracy and factuality of the information, acting as a verifier based on contextual data you provide. I routinely add API reference docs as context to my AI sessions when I want to verify release notes and other updates, for example. AI is generally welcome in enterprise writing scenarios, particularly with technical documentation, where the author is invisible, and where accuracy and clarity are more important than style.

However, in expressive genres of writing, such as personal essays, opinion articles, argumentative essays, blog posts, and more, AI is much less welcome. This is where using AI is met with accusations about AI slop, and rightly so.

My question is whether AI could also be helpful in more expressive genres, without becoming AI slop that everyone hates, including those producing it. I do think there’s a possible use case for using AI without losing your own voice, which seems to be the main concern. The strategy involves using AI as a research assistant to deepen your writing with a Bakhtinian “heteroglossia” strategy, which I’ll both explain and explore at length. In fact, the liveliness of the writing might emerge from this juxtaposition of multiple voices.

Heteroglossia

In general, good writing is informed by what others have said on the subject. It’s rare that we have a lot to say about a subject that no one else has said anything about. Any genuine inquiry usually includes a research component.

In my college days, I remember reading Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian literary theorist writing in the 1930s, on the idea of “heteroglossia” in texts (later published in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays). What stuck with me was Bakhtin’s idea that weaving multiple voices into writing brought the prose to life. That’s about all I remember about Bakhtin and heteroglossia, so I had to dig back into the text and get a bit more detail. In doing so, I was floored to see how relevant and revelatory Bakhtin and heteroglossia is within the context of AI-generated content. Bakhtin’s dialogic imagination might be one of the elements that separates soulless AI-generated writing from soul-filled human-written content.

I’ll try my best to unpack Bakhtin. My critical theory skills are somewhat rusty and he’s a bit opaque, as most philosophers are. (They’re wrestling with deep, complex concepts.) Basically, Bakhtin grounds his ideas by contrasting two different forms of writing: the poem versus the novel.

In the poem, the poet adopts more of a “monologic” approach to the content, expressing a single point of view with a specific style. Bakhtin describes this mode as a “monologically sealed-off” world (296) where the poet seeks a “unitary” language, stripping the word of others’ intentions to create an “Edenic” world of pure meaning (331). In other words, it’s writing as if you are the sole person on earth and act as if you completely own all the words and their meaning.

In contrast, with the novel, the writer embraces a much more dialogic (conversational) approach. The novelist doesn’t have this same Edenic world of pure meaning but instead welcomes more of a social heteroglossia. In other words, novelists immerse themselves in a language landscape with multiple layers of professional, generic, and social dialects (288). Novelists jump into the minds and voices of characters and settings, engaging in conversations with the reader (such as imagining responses and responding in advance), inviting readers into interactive explorations of thought, and more.

In a novel, there are many different characters and points of view all bumping into each other. The narrator traverses these different languages or perspectives (as in a busy marketplace with lots of conversations going on), wrestling with otherness. The novelist doesn’t just show characters; they “ventriloquate” through “social languages” that carry their own specific worldviews (299). This multiplicity of languages (the heteroglossia, or mixture of tongues) gives rise to an energy and vivaciousness in the language that pulls readers in, engaging them.

Deep dive into heteroglossia

In this spirit, let’s give voice to Bakhtin for our own bit of heteroglossia here. Bakhtin starts by describing how the poet typically adopts a monologic (single-voiced) stylistic approach, one that seeks to maintain “a complete single-personed hegemony over his own language” (297). Bakhtin writes:

“Stylistics [traditional formal analysis] locks every stylistic phenomenon into the monologic context of a given self-sufficient and hermetic utterance, imprisoning it, as it were, in the dungeon of a single context; it is not able to exchange messages with other utterances; it is not able to realize its own stylistic implications in a relationship with them; it is obliged to exhaust itself in its own single hermetic context. … It is precisely this orientation toward unity that has compelled scholars to ignore all the verbal genres (quotidian, rhetoric, artistic-prose) that were the carriers of the decentralizing tendencies in the life of language, or that were in any case too fundamentally implicated in heteroglossia.” (274)

In other words, the monologic approach imprisons language within its own self, robbing it of the meaning that surfaces when put in context with other speech, in dialogue. Bakhtin argues that traditional linguistics fails because it views the listener as a “passive” recipient—a view that creates “sclerotic” and “flat” discourse. Bakhtin continues:

“… Therefore, insofar as the speaker operates with such a passive understanding, nothing new can be introduced into his discourse; there can be no new aspects in his discourse relating to concrete objects and emotional expressions. Indeed the purely negative demands, such as could only emerge from a passive understanding (for instance, a need for greater clarity, more persuasiveness, more vividness and so forth), leave the speaker in his own personal context, within his own boundaries; such negative demands are completely immanent in the speaker’s own discourse and do not go beyond his semantic or expressive self-sufficiency.” (281)

Without more dialogic engagement outside him or herself, the speaker has nothing new to introduce into his or her own discourse. Semantically, the speaker resides in his or her own world of meaning, without crossing over into other semantic worlds. There’s no tension or uncertainty in the language or meaning, no contextual energy.

Now contrast this monologic speaker with a dialogic one. As soon as dialogic speakers engage in dialogue, they have to contend with other meanings and interpretations. They can’t blanket themselves from the larger semantic connections of their words, and this creates tension and friction to overcome. For the novelist, language is never “virginal” or “unuttered”; it’s always already “overpopulated” with the intentions of others. Bakhtin explains:

“Indeed, any concrete discourse (utterance) finds the object at which it was directed already as it were overlain with qualifications, open to dispute, charged with value, already enveloped in an obscuring mist—or, on the contrary, by the “light” of alien words that have already been spoken about it. It is entangled, shot through with shared thoughts, points of view, alien value judgments and accents. The word, directed toward its object, enters a dialogically agitated and tension-filled environment of alien words, value judgments and accents, weaves in and out of complex interrelationships, merges with some, recoils from others, intersects with yet a third group: and all this may crucially shape discourse, may leave a trace in all its semantic layers, may complicate its expression and influence its entire stylistic profile.” (276)

When you venture forth into an alien/external context, you have to contend with meaning, just as I’m doing now by trying to interpret Bakhtin. I’ve used Bakhtin’s same words in my lexicon (alien, dispute, light, agitated, tension-filled, recoils), but now I’m forced to wrestle with their semantic meaning in ways that others, primarily Bakhtin, are using the words, parsing my meaning against Bakhtin’s meaning, who is likely parsing his meaning against other uses. This reflects Bakhtin’s core principle: “The word in language is half someone else’s. It becomes ‘one’s own’ only when the speaker… appropriates the word” (293). Bakhtin continues:

“…In the actual life of speech, every concrete act of understanding is active: it assimilates the word to be understood into its own conceptual system filled with specific objects and emotional expressions, and is indissolubly merged with the response, with a motivated agreement or disagreement. To some extent, primacy belongs to the response, as the activating principle: it creates the ground for understanding, it prepares the ground for an active and engaged understanding. Understanding comes to fruition only in the response. Understanding and response are dialectically merged and mutually condition each other; one is impossible without the other. (282)

Bakhtin says this dialogic engagement evokes a response; we interact like dueling banjos, one with another, in a dialectic, potentially upward spiral of exchanges that derives its energy from the juxtaposition, like two bodies of mass finding gravity from their proximity. Bakhtin continues expanding on the dialogic imagination:

“Thus an active understanding, one that assimilates the word under consideration into a new conceptual system, that of the one striving to understand, establishes a series of complex inter-relationships, consonances and dissonances with the word and enriches it with new elements. It is precisely such an understanding that the speaker counts on. Therefore his orientation toward the listener is an orientation toward a specific conceptual horizon, toward the specific world of the listener; it introduces totally new elements into his discourse; it is in this way, after all, that various different points of view, conceptual horizons, systems for providing expressive accents, various social “languages” come to interact with one another. The speaker strives to get a reading on his own word, and on his own conceptual system that determines this word, within the alien conceptual system of the understanding receiver; he enters into dialogical relationships with certain aspects of this system. The speaker breaks through the alien conceptual horizon of the listener, constructs his own utterance on alien territory, against his, the listener’s, apperceptive [context-assimilating] background.” (282)

This intersection with the alien context, engaging in dialogue with another mind, is exciting. It’s producing energy and interest. The story starts to emerge, and points of friction are felt that inspire the speaker with new conflicts and frictions to address, or to absorb and expand on. In the novel, this intersection might take the form of a “hybrid construction”—an utterance that “belongs, by its grammatical… markers, to a single speaker, but that actually contains mixed within it two utterances, two speech manners, two styles, two ‘languages’” (304). For example, a narrator impersonating another’s style with a sarcastic tone.

Can you see how the context with other languages and the dialogic imagination helps infuse writing with a sense of liveliness and meaning? Ultimately, Bakhtin says “Discourse lives, as it were, on the boundary between its own context and another, alien, context” (284). The meaning of language and meaningfulness of it are dependent on its larger context.

Bakhtin has a lot more to say on this subject, and he goes beyond my scope here. Basically, to write is to engage in this wrestling match with meaning. Meaning emerges, he says, in the space between our own use of the words and the context provided by others. He famously notes that “Discourse lives, as it were, on the boundary between its own context and another, alien, context” (284). When we write, we’re wrestling with the meaning others have imputed to these words, much the same way I’m wrestling with Bakhtin’s ideas and trying to formulate my own ideas about what he means but in a new context.

This element of heteroglossia often provides an engagement factor to content. As I’m writing right now, about the need for a variety of voices in a personal essay, I’m bumping up against Bakhtin and his ideas here, and in this wrestling with others, my writing is taking on a new sort of feeling: the sense of a mind thinking. I’m not just stating an idea as the monologic voice of a personless encyclopedia article. I’m working through other authors and perspectives, other terms and language, and trying to find my way to the goal I have through these other voices. Imagine me writing this same essay, but not referencing or navigating any external voices — the writing would fall flat. But with the external sources, I’m forced to navigate through them, to align or misalign with reasoning and judgment.

I think this sense of navigation through what Bakhtin calls a “dialogically agitated and tension-filled environment of alien words, value judgments and accents” (276) is what generates a mind in motion—a Montaignesque or Descartes-like sense of thinking and wrestling with those other ideas. This mind engaging with other perspectives creates a sense of soul. You can feel it. The voice isn’t monologic; it’s dialogic. Bakhtin warns that when a writer is “deaf” to this organic double-voicedness, the work becomes a “closet drama”—a lifeless imitation where the language feels as “awkward and absurd” as stage directions (327). In the same way, when you remove the diversity from language, you end up more often than not with slop.

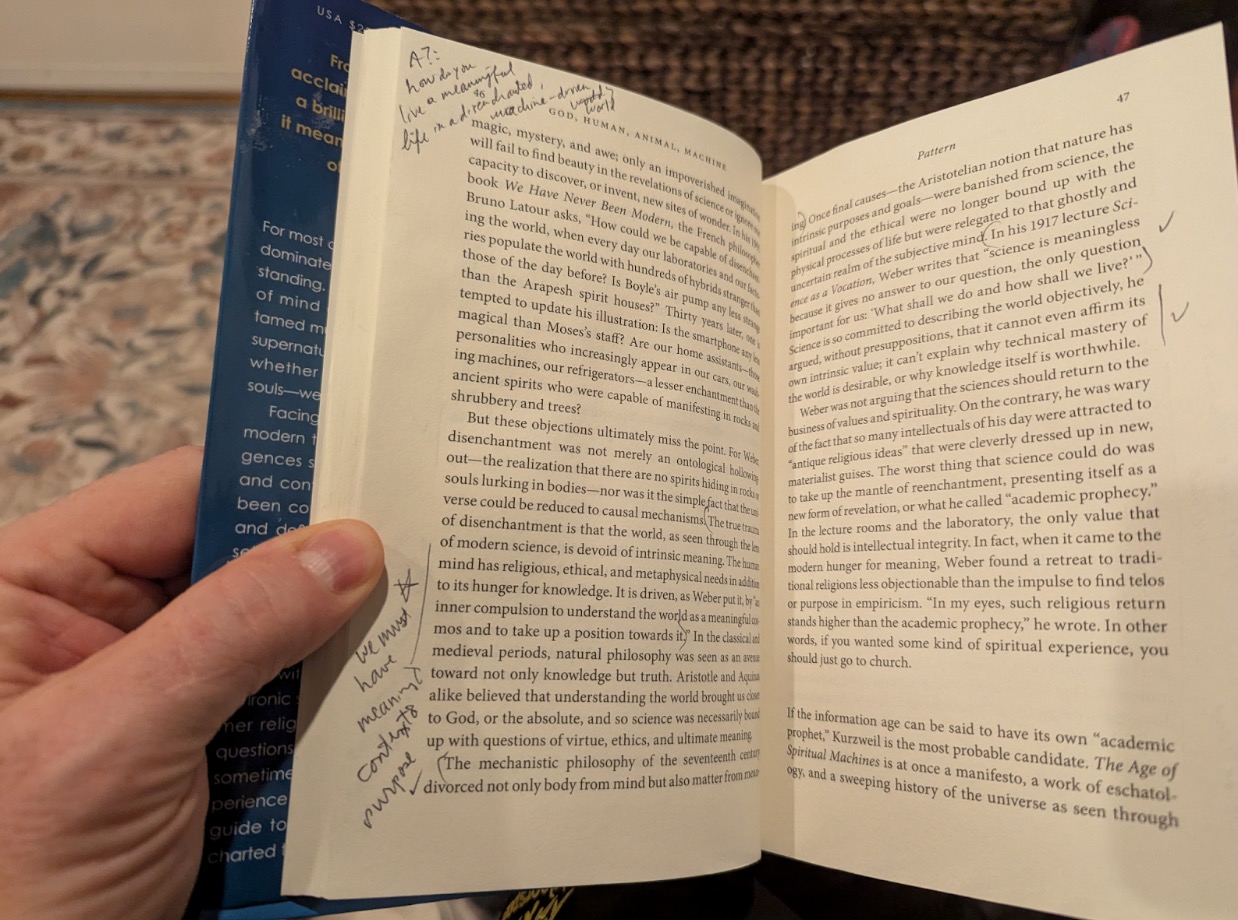

The element of heteroglossia is precisely why Meghan O’Gieblyn’s prose comes to life in God, Human, Animal, Machine. O’Gieblyn freely brings in the first-person (the “I”) into her writing, but despite the few plot points in her book (going to a conference, addressing questions from the audience, etc.), her intellectual journey is where the true dialogism happens. She mingles with Aristotle, Neils Bohr, and Ray Kurzweil, providing her own commentary and analysis. In Bakhtinian terms, she’s orchestrating a “marketplace of ideas,” allowing her own intentions to be “refracted” at different angles depending on the “socio-ideologically alien” nature of the voices she invokes (300). I love the term “refracted” because it perfectly conveys the bending and wrangling of ideas required when you move through alien contexts.

I’m convinced that it’s the heteroglossia that gives O’Gieblyn’s text energy (along with many other personal essayists, who browse different authors and spaces in meandering ways). There’s no sense of O’Gieblyn’s content being machine written because the “social atmosphere” (277) of the words makes the facets of her arguments sparkle. In this post so far, I’m 1,000+ words into it and have only mentioned a few other voices. I could venture into Julia Kristeva on intertextuality, Tzvetan Todorov and narratology, Emmanuel Levinas and otherness, and more. But hopefully I’ve communicated my point already.

Just bringing in a multiplicity of voices and perspectives isn’t enough. Bakhtin says the novelist must organize these voices into a cohesive, harmonious way — “maintain[ing] the unity of his own creative personality and the unity … of his own style” (298). In interweaving quotes into my own essay, I’m afraid I haven’t done such a good job at maintaining my own creativity unity here, but the attempt is here. We want the reader to steer us through these ideas in a graceful, conversational, and fair way. In fact, in O’Gieblyn’s book, I wanted fewer external voices and more O’Gieblyn. Striking this balance between self and other is key for the writer to be a pleasing read.

From Bakhtin’s heteroglossia to AI model collapse

Now let me make a radical pivot into the present with Bakhtin and compare the idea of monologism and heteroglossia (from Bakhtin’s essays originally written in 1934 and 1941) to AI model collapse today. In 2024, a troubling research paper came out called “AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data.” It argued that AI trained on AI-generated content suffers “model collapse”—a degrading of output quality such that the model loses its ability to reflect reality.

The paper argues that this degradation happens because of the disappearance of the “tails” of the data distribution. With each new model version, when the model is exclusively trained on its own output, the prediction algorithms focus on the most probable, central part of the bell curve. The tails—those rare, creative, or bizarre data points that make up the jagged, alien edge of human thought—”get washed away.” As the copy of a copy of a copy reduces these fringes, the model arrives at a “mean representation” of the data that eventually collapses into nonsense (1). In the paper’s examples, by the ninth generation, a model asked about architecture begins babbling repetitively about “blue-tailed jackrabbits” (2). It loses its connection to the living world.

The problem with AI-generated content, Bakhtin might say (I’m speculating here; obviously Bakhtin predates generative AI and AI slop by decades), is that AI-generated content adopts a monologic style. That monologic style is inherently centripetal; it exerts a centralizing pressure to align on a unified, single “authoritative” voice (274). Bakhtin warns that this orientation toward unity eventually makes discourse “sclerotic” (292) and “histological” (like dead tissue under a microscope) (275)—it turns the living speech into a dead specimen.

In contrast, heteroglossia is a centrifugal force. It embraces the edge of content. On the outside edge, outside the bell curve of predictability, content includes more fringe or extreme, radical, and subversive takes. The outer edge is less predictable; it’s more alien, unexpected, and bizarre. It isn’t smooth. It’s where language is “still warm from struggle and hostility, as yet unresolved and still fraught with hostile intentions and accents,” Bakhtin would say (331). The loss of this edge content leads us instead toward monologism. And monologism leads to model collapse.

In short, not only does writing need heteroglossia (many different tongues) to add meaning and interest, AI models also thrive on this difference. Sameness is a death sentence for both soul and software. This finding should lead us to celebrate those edge voices putting centrifugal pressure away from the center to keep language, and our AI models, alive. Welcome subversive language and be curious about otherness. Trespassing beyond the fenceline of normal, perhaps skirting danger, is what makes prose exciting (and AI models coherent).

Takeaways and a new approach to using AI with expressive writing

Let’s now move toward practical takeaways and a recommended approach to using AI with writing (remember my original aim, which is to rescue expressive writing from prohibitions with AI). If heteroglossia (especially bringing in alien contexts) is vital to any personal essay, can AI help here without diluting your own voice and language? Yes, and I think this technique works in a way that’s mostly acceptable. I’ll explain three strategies:

- Use AI as a research assistant

- Use AI as a verification tool

- Use AI for the alien perspective

1. Use AI as a research assistant

The first technique is to use AI as a research assistant. Consider this approach:

- Write out a draft of a blog post using your own thoughts, voice, and words. No AI at this point. The blog post could be 500 words or 3,000, depending on how much you have to say.

- Plug your post into Gemini Deep Research (or similar) and ask AI to research the topic of your post for you. Read the lengthy report.

- From the research report, identify several sources mentioned that you think are significant in the discussion.

- Read the sources and pull out some interesting quotes or passages.

- Now make a second pass through your essay and interweave/reference the quotes as desired into the body of your content.

- Follow up external quotes with summaries and analyses of these other voices.

- Ask AI to verify that your interpretations of the source are correct.

You could also task AI to do steps 3 through 7 in varying degrees (there’s a whole spectrum of possible AI implementation here), but if you use too much AI, you’ll be abdicating your own essay and voice to the algorithm. You have to keep a hold of it yourself if you want the writing to be meaningful to you. Don’t give away your words, in short. Just use AI to enrich, not usurp, your voice.

Using AI as a research assistant can help you identify relevant voices among a sea of competing conversations. We don’t have endless time to research the topics we write about, reading books and articles end to end looking for the relevant chapters and passages—though doing so would of course be more enriching.

In using AI as a research assistant, you aren’t diluting your own voice because you’re using AI to help identify and summarize other research and voices, bringing and weaving those other perspectives into your own. And AI is really good at summaries.

Summary is one format in which we don’t expect much personal voice. This use of AI aligns best with the way we use AI with technical documentation in the enterprise, such as using AI to summarize all the technical changes in an API release. Summary doesn’t tend to be an offensive use of AI.

2. Use AI for verification

Now let’s move on to another use of AI: verification. I’m currently reading Meghan O’Gieblyn’s God, Human, Animal, Machine. It’s impressive how well-read O’Gieblyn is, not just the scope of authors she’s conversant with, but how well she simplifies the messages of philosophers and theorists such as Descartes, Kierkegaard, Bostrom, Bohr, and countless others. (I have no idea how she keeps track of all these quotes and summons them at will for the topic at hand — it’s really impressive.)

For a novice / amateur hack like me, I’m not confident in my ability to summarize major philosophers. I sometimes struggle to follow the details of the philosophical arguments, and when I do quote others, I want to be sure I’m accurately representing their ideas. It’s the same impulse I have in technical documentation: I check my content against the reference material, and I do so multiple neurotic times. Bakhtin would argue that my need to check and verify meaning is because a word is “half someone else’s” (293). More importantly, if I misrepresent a source, I’m not engaging in true dialogue, I’m just performing a monologue with a puppet. I want to be sure I’m actually engaging with a fair, legit representation of an author’s ideas.

I was recently writing a book review of If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares. I wanted to help remember and understand the details of their arguments better, so I found an online PDF of their content, added it into NotebookLM, then presented my draft blog post there to check that I was correctly interpreting their arguments.

This process helped in two ways. First, I felt more confident that I was accurately representing the author’s ideas. When critiquing someone, it’s easy to provide a straw man argument. AI acts as a neutral third party here, providing the author’s arguments in a thorough, fair way.

It’s common to be accused of taking ideas out of context or “cherry-picking” an argument. AI can help ensure you’re portraying the author’s actual work. This intellectual honesty is what turns a “histological specimen” of a quote into a living, “active understanding” (281), Bakhtin would say. Usually AI tends to present someone’s ideas in an almost generous light, giving them more credibility than I think they deserve, but in a constructive, helpful way.

Note that I admit that there’s benefit to wrestling with a text on your own. It can be too easy to abdicate the role of interpreter to AI and let these tools perform their magic simplification. There’s no doubt a loss of critical reading that takes place in doing so. Warner says that reading (like writing) is an emotional experience. When AI creates bullet points of another’s work, it removes our struggle and engagement with that text, which is a loss. Limiting ourselves to the summary removes our emotional engagement entirely, making the text much less interesting and meaningful to the reader. Without more of a pull towards the other, the writer’s dialogic imagination falls flat, because the writer is talking with a text he or she cares little about.

You can’t reduce a book to a list of bullet points and still get the same reading experience. As one of my colleagues pointed out, just as we experience emergence in writing (“emergence” referring to the spontaneous surfacing of ideas that have no clear origin to what produced them), emergence also happens during reading. O’Gieblyn says of her writing process, “at some point the thing I have made opens its mouth and starts issuing decrees of its own. The words seem to take on their own life, such that when I am finished, it is difficult to explain how the work became what it did.” This emergence happens at the boundary between my own mind and the text, as Bakhtin would say. If I offload the interpretation to AI, I short-circuit the likelihood of emergence during reading.

O’Gieblyn is wary of emergence, as she likes to maintain control over her own creative process, and pushes back against the black box algorithms of both AI and religion that favor the mystical. Or rather, she pushes back against obedience to systems that we can’t understand. But as even a blogger, I love the idea that when I start writing a post, I never quite know what I’ll discover or how it will all turn out.

Overall, having AI help me understand my sources makes me more inclined to engage with topics I might otherwise avoid. If AI can be a tool that helps us in that wrestling match, furthering our understanding, and thereby encourages more engagement with the text, is it not a valid tradeoff?

One more point about verification. When writing, it’s easy to fall into the mode of finding sources that support the points we already have. I find that AI pushes back against these easy interpretations, making the sources we cite more problematic. But these problems, the rough points and misalignment, are exactly what makes us engage in a more interesting, lively way. The sources that somewhat support but also kick back make these texts more of a wrestling match that we have to engage with, think through, rather than just use as puppets of pretend support. And that engagement/struggle inserts the soul into our writing.

3. Use AI for the alien context

Finally, there’s one more use of AI that’s extremely helpful. Ethan Mollick argues in Co-Intelligence that the alienness of the AI algorithm can help provide an external perspective that we need, helping us see past our own biases. Mollick explains:

“And AI can be very useful. Not just for job tasks, as we will discuss in detail in the coming chapters, but also because an alien perspective can be helpful. Humans are subject to all sorts of biases that impact our decision-making. But many of these biases come from our being stuck in our own minds. Now we have another (strange, artificial) co-intelligence we can turn to for help.” (Chapter 3, “Four Rules for Co-Intelligence,” under the section for Principle 1:)

When writing, we’re frequently blinded by assumptions. To get an outside perspective, I take an early draft and upload it into NotebookLM, then make an audio deep dive or video explainer. Then I listen to it and see if the AI gets my point, or what the AI hosts choose to focus on and the directions they take my ideas.

Listening to my content rendered by the alien algorithm helps me see my content with more distance. In Bakhtin’s terms, I’m seeking a “responsive understanding” (280)—an active listener I can use to “get a reading on” my own words (282). In other words, how does the reader assimilate my words and meaning into their own alien context? Does my meaning align with the listener’s meaning, and if not, how do I refract my words to better achieve my goal?

Again, you can see the dialogic mode between writer and reader, speaker and listener, is shaping the content. I can tell if my points come across or are missed; I can tell if my argument is interesting or lifeless. And I use that response to inform my next words.

Sometimes I’m drawn in by the AI’s flattery (for example, “your connection between Bakhtin and model collapse is brilliant!”), so I have to watch for that. But overall, hearing my own essay as a podcast is like stumbling into a cafe and overhearing one reader explain my post to another person at an adjacent table. It provides a fascinating and helpful perspective. In short, distance.

When I return to my draft, I might incorporate ideas gleaned from the AI, or not. As Kurzweil says, our ideas become indistinguishable in origin (human or machine) as there’s a constant back-and-forth. We end up forming a “heteroglot unity” (284), Bakhtin would say, a back-and-forth building of ideas that might be the new reality of creative work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I’ve argued that AI can be helpful to expressive writing in at least three ways:

- Research assistant: helping us weave in the “alien” voices that bring prose to life and stop it from becoming a monologic “specimen.”

- Verifier: grounding our work in “active understanding” so we don’t accidentally silence the sources we’re trying to engage with.

- Alien perspective: providing the “responsive understanding” we need to see our own arguments from the outside.

Just as I’ve argued here in my essay, I used AI to help verify or identify quotations, and make sure I’m accurately representing and interpreting Bakhtin and others. I still spent hours reading Bakhtin at the kitchen table. I probably need to read the entire text again, to be honest. But AI helped me engage with him in a way that was fun, and I’m confident that I’m relaying his points well here without giving up my own voice.

All of the techniques I’ve described don’t result in AI slop. Instead, they help take writing to the next level. Some of my most popular posts in 2025 (such as The isolation and loneliness of tech writing may get worse as AI accelerates and 12 predictions for tech comm in 2026) used these methods. I encourage you to experiment with AI not to replace your voice, but to expand the social atmosphere in which your voice lives. Try it out, experiment, and engage with these other voices, even, and perhaps especially, when that voice is an alien one.

Works cited

Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, University of Texas Press, 1981. See The Dialogic Imagination (Excerpt).

Warner, John. More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI. Basic Books, 2025.

Kurzweil, Ray. The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI. Viking, 2024.

Mollick, Ethan. Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Portfolio/Penguin, 2024.

O’Gieblyn, Meghan. God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning. Doubleday, 2021.

Related resources

Also relevant but not used, AI Can Teach Our Students the Art of Dialogue, by David Weinberger, MIT Press.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.