Using curiosity to decenter

- Overview of the technique

- Rumination anxiety

- Cognitive decentering prompt

- Social partners for decentering conversations

- Links between curiosity and anxiety

- Decentering in the broader context

- Asking the right questions

- Questions not just to decenter anxiety, but for creative exploration

- Conclusion

- Works cited

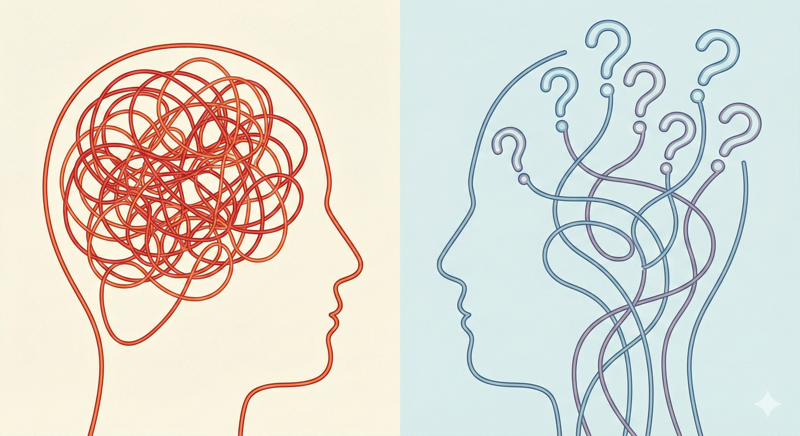

Overview of the technique

Here’s the technique. When I feel stress, boredom, confusion, or some other form of agitation, I first recognize the event, and then I ask myself three questions about it. In other words, I become curious about it. The act of asking questions triggers some kind of power shift in my brain from the amygdala (where fight-or-flight modes operate) to the prefrontal cortex (where more decision-making and executive function operate). This shift defuses the emotional strength of the agitation, leaving me calm and reflective — curious — rather than wound up and rabbit-holing. And with the right question, the issue often becomes not only less threatening, but interesting.

The number of questions isn’t magic, and I could ask just one or a dozen. The questions could be anything, really. Just get curious. Questions about intent usually work well, as it’s easy to misinterpret another person’s actions; when you ask what their intent might have been, it’s much easier to see them in an understanding light. The point is this: the mere act of becoming curious and transitioning into a question mindset (no matter what questions you ask) seems to trigger this amygdala-to-prefrontal-cortex power shift, which consequently nips any rising tension level and resets stress levels.

When I’m actively curious, my stress level remains low all day long, like a 1 on a scale of 1 to 10. Usually bad things happen when we operate at a stress level of 7 or higher. That’s when we’re prone to erupt in anger or have unexpected outbursts over unpredictable triggers (think how seemingly small traffic mishaps quickly turn into deadly road rage). In short, we become walking powderkegs, ready to blow at the smallest spark. Instead, keeping my emotions at a Spock-like level of calm allows me to analyze and process events and ideas in a much more enjoyable way.

Rumination anxiety

The questions technique works pretty well, but it’s possible to be so consumed by a thought or emotion that just asking questions doesn’t accomplish the decentering. Like others, I’m prone to “rumination anxiety” (as it’s called) every now and then. In this state, no matter how many questions I think up, I just can’t shake the rabbit-holing thoughts. I can’t quite step out of the experience to look at it more externally/objectively.

The topic can be trivial, and I don’t want to go into any detail here, though mentioning this might give others the impression that I struggle with this a lot. I don’t. But everyone occasionally does — we all spiral a bit from time to time, rehearsing bad scenarios or running worst-case outcomes over and over in our heads.

The last time this happened (regret over something I said in a meeting…) I tried something new. I opened a session with Gemini and told it I wanted to play a game. I called the game “question-answer-question.” I would ask it a question, and its job would be to answer the question and follow it with a question back to me. I would answer its question and fire a question back at Gemini. Then Gemini would answer my question and ask me a question back. And so on.

I did this question-answer-question game for about 20 minutes and discovered a few things. First, the technique actually worked. It liberated me from the particular rumination loop I was struggling with at the time. At some point in the conversation, I unlocked a new way of seeing the issue that changed my perspective enough that I no longer spiraled about it.

But also, having Gemini respond like this further got me outside of my head, because the “alien algorithm” helped me see things differently. In fact, at one point, Gemini pointed out an irony about the situation that was brilliant. This was an irony I was incapable of seeing while locked in an emotional rumination loop.

Cognitive decentering prompt

If you’d like to try the game, here’s the prompt:

Simple version:

I want you to play a psychological cognitive de-centering game with me. I’ll ask you a question and you answer it. After your answer, follow it up with a new question along the same lines.

I initially said this post would only be a napkin sketch, but it turns out I did read a few articles, hoping to deepen my understanding. In “Prompting Large Language Models with the Socratic Method,” Edward Chang argues that you can get a better output from LLMs if you engineer prompt templates that guide the LLM through the Socratic method. By Socratic method, this might involve interrogating definitions, looking at counter-arguments, exploring alternative viewpoints, examining evidence for assertions, cross-examining (elenchus) assertions, employing counterfactual reasoning, challenging reasoning, and more.

Although Chang’s article doesn’t touch upon the psychological application of Socratic reasoning templates for the scenarios I’ve described here, you could program the LLM to apply Socratic inquiry to the emotional state you’re trying to observe from the outside. This tradition of dialogic inquiry has essentially been the foundation of Western critical thought, so why not distill it into a rubric that can guide the LLM toward a more productive set of questions to decenter you?

If you want more of a Socratic spin on the previous prompt, more in line with Chang’s approach, try asking questions related to the following:

- Definitions

- Evidence

- Alternative perspectives

- Counterfactuals (what-if scenarios that run counter to reality)

- Comparison and contrast

Although I usually play this questioning game with myself, it can also be fun to play with AI. I tend to learn more. I created a Claude chat configured with Chang’s Socratic reasoning here: https://idbwrtng.com/decenter

However, honestly the prompt doesn’t work so well. Reason being, Claude does more of the heavy lifting with questions. That’s not the point. The point is for the human to start asking questions. The goal of the exercise is to shift your mindset into asking questions, toward curiosity rather than judgment. If you outsource the question-asking, the whole exercise fails to make that mindset shift. At any rate, you could tweak the AI prompt more to make AI more of a rubber-duck style sounding board rather than a Socrates-like partner driving the questions and perspective shifts.

Social partners for decentering conversations

I told my wife about this game I played with AI, and her first reaction was, why didn’t you play this game with me instead? In fact, she was just relaxing in the other room. Perhaps I was embarrassed by the triviality of my particular rumination. But also, not everyone plays this game well. Sometimes other people stress me out more, and we both catch an amygdala wave and start riding it together in a downward spiral. This phenomenon of the other person adding to the emotional state is sometimes called “co-rumination” by psychologists.

In contrast, the calm, assured equanimity of the amygdala-less AI can be a benefit in these situations. Reason being, humans are empathetic, and so emotions can be contagious; we soak up another person’s enthusiasm, or worry, or spiraling. But the AI doesn’t. The AI is predictably level-headed, constructive, and won’t exude a depressing vibe that adds to an amygdala hijack. Chang says that LLMs don’t use sarcasm or emotions, making them more suitable partners. He explains:

The Socratic method may not always be effective or useful in human interactions, especially when one of the two players is authoritative, emotional, or abusive. However, when the expert partner is a language model, a machine without emotion or authority, the Socratic method can be effectively employed without the issues that may arise in human interactions.

In fact, when I get into discussions with my wife, her emotions often get amped up, as she puts her full energy into her logical arguments. She’ll often be frustrated if I don’t grasp the alternative perspectives she’s arguing for, or if I miss some of the nuances of her arguments. Sometimes, depending on the topic, she’ll really double down and leave everything on the floor in pursuit of some end. Most of the time when our kids ask her for help with math, even if she helps them finally understand, they’re often crying at the end. Strangely, this passion is what I love about her!

So AI might be good in these psycho-therapeutic situations. You need the calm objectivity of a partner who is engaging in Socratic inquiry with you; in fact, if Socrates were to appear via a time machine and engage with me, I think he’d be kind of a disagreeable ass, always showing me how wrong I am about everything.

However, there are some risks to using AI. AI’s sycophantic tendencies might lead you down imaginary worldviews that deviate from reality. There are plenty of stories about people becoming deluded about crackpotted world views (inventing a new math language), or falling in love with their AI (“Leo”), or deciding to commit suicide (insulating yourself from real people who can actually help).

But I think these unfortunate outcomes are unlikely in this decentering questioning scenario I described. The whole purpose of the exchange is for AI to get you to change your mind, basically, not to go along with it. This pushback against your current trajectory/spiral runs counter to the sycophantic behavior of a yes-man virtual companion. The approach to cross-examination and Socratic questioning provide a strong pull against sycophantic drift.

Links between curiosity and anxiety

The question technique to decenter connects in uncanny ways to brainstorming techniques in the creative space. Here’s where psychology intersects with creativity in unexpected ways. About 20 years ago, back in a creative writing program, I used a technique for brainstorming that involved the following:

- List 10 questions about a topic.

- Answer the questions.

- Pick the most interesting answer.

- Ask 10 more questions about that answer.

- Answer the questions.

- Pick the most interesting answer.

- Ask 10 more questions about that answer.

- Continue on until you’ve hit on something truly interesting.

In brainstorming techniques, Chang would say this method (more like exploratory Socratic questioning) correlates with a midwifery approach (maieutikos from the Socratic method), helping bring forth an idea you already possess. This iterative brainstorming technique works quite well, though I admit that asking and answering my own questions (figuratively delivering my own baby) requires more energy to get somewhere. But it works, and probably accounts for my confidence in being able to fill any page, any time, as often as I want.

(BTW, the technique had flaws. It sort of creates a sense of jumping around in the writing. But it usually moves the discussion to interesting spaces.)

At any rate, I introduce my brainstorming technique because it provides a segue into the link between curiosity and anxiety. Apparently, curiosity and anxiety exist as two opposing poles along the same dimension, according to Bischof (as explained in Hilmerich et al). In other words, the opposite of anxiety isn’t courage (or calm), but curiosity, they say.

Hilmerich et al sought to find neuroimaging evidence for the model Bischof explained linking these two modes (curiosity and anxiety) in the brain. They found that there’s a part of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) that seems to light up with incoming information, and then either signals the amygdala or the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) depending on how that incoming information is assessed.

The incoming stimulus is assessed against one’s “enterprise,” which refers to the amount of novel information a person strives for. There are two different outcomes your brain takes with incoming information:

- If the incoming information is lower than your enterprise (for example, maybe a weather forecaster predicts an “atmospheric river” — which is novel information that fits within your comfort zone), then your NAcc lights up, and curiosity grows.

- If the information is higher than your enterprise (for example, you receive a letter from the IRS stating you owe $40k in back taxes — novel information that doesn’t fit your comfort zone), the amygdala activates and your brain starts triggering anxiety.

(I’ve simplified this as more of a routing switch than it actually is; apparently there are more complex intraregional connections, but that’s beyond my intent here.)

Linking anxiety and curiosity as opposite poles along the same dimension is significant for my investigation here, because I’m arguing that applying curiosity through decentering questions mitigates the potential anxiety and emotional spiraling from rumination loops or even just general agitation.

Hilmerich et al conclude on an optimistic note, saying, “The critical assumption here is that the same stimulus can lead to anxiety or curiosity, solely depending on the subjective expectations of the perceiving individual.” In other words, you have some influence as to whether the novel information signals the amygdala or NAcc.

To connect Hilmerich et al to decentering (which they don’t address), by decentering yourself from the incoming information/agitation, you can better persuade the ACC to involve the NAcc — and hence curiosity — rather than the amygdala and subsequent anxiety. With the amygdala in the backseat, you won’t experience the state where the amygdala hijacks control of the prefrontal cortex (where the brain’s decision-making and executive function reside). In Star Trek characters, you can be Spock instead of Scotty.

Decentering in the broader context

Let’s broaden the research and find an article that focuses more squarely on decentering. Bernstein et al look at the underlying constructs across many related psychological theories, from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to metacognitive awareness theories, cognitive distance, cognitive defusion, and more, even including mindfulness and meditation. From these closely related constructs, Bernstein et al propose a theory of “decentering” to provide a sort of through-line that runs through the core of them all.

In their model, decentering involves “three interrelated processes — meta-awareness, disidentification from internal experience, and reduced reactivity to thought content.” In other words, the process involves three steps:

- Meta-awareness involves recognizing the agitated, emotional state;

- Disidentification involves extracting yourself into becoming an external observer of the emotional state;

- Reduced reactivity is the improved well-being and reduced stress that results from acting as this external, analytical observer.

They describe decentering with an actor metaphor, writing: “People can be both actors engrossed in the unfolding story of their minds’ experience of the world as well as third-person observers of that subjective experience.”

I’m not sure why our brain has such meta-awareness capabilities — this ability to step outside of ourselves and observe and recognize a state, as if it’s happening to someone else. Bernstein et al say “the capacity to shift experiential perspective — from within one’s subjective experience onto that experience — is fundamental to being human.” This “disidentification from internal experience” (removing ourselves from the center of an activity) is the first step in nearly every one of these highly related meta-cognitive therapies.

I like the actor and observer metaphor, but let’s add in some theatre and spectator audience elements to complete the picture. In short, with decentering, you’re an actor who leaves the stage and goes to sit with the audience. Sitting in the audience, you observe yourself acting on the stage. At this point your mind splits into two experiences — the actor still on stage, and the audience member watching the play.

It’s easy to imagine walking off the stage and sitting down in the audience chairs, but much harder to do when you’re wrapped up in some emotional loop. The emotion could be anger, annoyance, or regret. In fact, yesterday I spent much of the day short-tempered and only partially realized I was in this constant stage of agitation later in the day (at 3pm I wondered, why am I in such a pissy mood today?). So the first step is to recognize the agitated state when it arrives (the meta-awareness — like, oh, I’m experiencing [x]). Is it annoyance, anger, boredom, worry, despair, glee, satisfaction? It could be anything — some stressor usually prompts recognition.

Once you recognize the state, that’s the time to start asking questions. Bernstein et al don’t delve into how an individual shifts from actor to spectator, nor argue that asking curious questions is the lever to decenter. But in skipping this detail, it simplifies the disidentification model. I think disidentification with a thought is really hard to achieve without some method for doing it. In my experience, it’s asking the right questions (more on that in a minute) that allow me to walk off that stage and sit in the audience. Each question turns the frame just a bit:

- Question 1 gets me moving toward the side of the stage.

- Question 2 gets me beyond the curtain.

- Question 3 gets me to the audience platform.

- Question 4 gets me a few steps closer to an audience aisle. And so on.

By the time I’m well into a question and answer session, I’ve moved firmly into that audience chair and am seeing the play, which I myself am still in, but not fully. My mind has sort of detached as a semi-independent observer.

Asking the right questions

Different decentering techniques employ a variety of questions. For example, some say to explore questions of intent, reframing, or exploring opposite points of view. All of these are good questions. However, the type of questions to avoid are recriminating questions, like “Why am I such an imbecile?” “Why do I always let people down?” “Why am I such a failure?” “Why does everyone hate me?” Pretty much any question that begins “Why do I always …” will amplify the ACC’s interpretation of data as a threat for the amygdala to handle, which grabs hold of your emotions in a fight or flight state of anxiety/panic.

Instead, the questions should seek to look at the problem from an unfamiliar angle (decentering). See it differently (off center, non-egocentric) than you’re currently seeing it. Not just looking for ways to see something in a positive light, which I feel is cliche and doesn’t work well long-term. Rather, see something from a different angle. Questions like, “What’s the purpose of that [thing]?” “What’s the historical origin of [x]?” “Why was [x] invented?” “How are other groups using [x]?” “What are the different components to [x] and how do they work together in the system?”

Questions not just to decenter anxiety, but for creative exploration

There could be value in following a rubric of questions that lead down a specific path. But so many of the psychological question rubrics are designed to offset trauma and anxiety/worry. They’re mental-health related. While I experience anxiety/concern like everyone else and use these techniques to decenter away from that agitated stage, I also use these techniques for fun. Because ordinary life, working as a technical writer, is kind of boring.

I like the rush of seeing something new. This is what I wrote about in my post Seeing invisible details and avoiding predictable, conditioned thought. Writing (and art) is about ways of seeing. Rob Walker’s Ways of Noticing has been fascinating for me. The idea that if you look at something from a different perspective, the thing takes on an entirely different shape. This is why I read the Dumbify blog — I like inverting perspectives on the ordinary to discover that a new angle reveals a wholly different story and idea that you didn’t see. I believe we’re surrounded by these opportunities.

One time I was sitting in a high school gymnasium at a less-than-exciting school event for my daughter (an awards event). At about 20 minutes in, while the host droned on about something banal, I started looking at the banners hanging on the walls, wondering why the school excelled in Judo but not football, whether gymnasiums like the one I was in had changed much since they first hung a banner in it, what the stories were behind the pictures hanging on the walls. I imagined the events that must have taken place in the gym 20 years ago, 30 years ago, or 75 years ago. Suddenly, I was at the most interesting event I’d been at for a while.

As an ultimate test of curiosity, while at a diner waiting endlessly for food, I once started examining the patterns on silverware. The patterns were shell-like waves, or patterns representing a “harvest” motif. I started digging into these patterns, wondering why I’d so rarely noticed these patterns on silverware and what they could mean, or the story behind them. My wife, who has ADHD, suddenly caught this line of inquiry and went down a rabbit-hole exploring silverware design patterns for the next hour. After a while, I was trying to bring her out of it. She just kept going and going, fueled by what she was learning online and combining it with her weird trivia-like superpower knowledge of everything. (After a while, I regretted asking the question.)

So when I read about psychology studies that focus entirely on questions to decenter people from anxiety loops, the mental health angle is only part of the picture. I’m equally interested in brainstorming. And also, I think the act of asking questions is more important than the actual questions you ask. Like taking pictures at an event, you have to take a lot of pictures (ask a lot of questions) until you stumble upon the one or two really interesting ones worth exploring. The main principle is to ask decentering questions — questions that don’t center everything back on yourself.

Think of the question topics like sitting in different chairs in that audience watching the play. Start out in the front row, but then move back to aisle 20. Then move to the mezzanine. Then move to the seat that has concrete pillars partially obstructing the view. See if you can walk across the catwalk for a while. Then go down to the orchestra pit. Then stand where the usher is standing. Then to a high-priced balcony private box seat. Then to the lighting and sound control board. Move all around to see the play from different angles.

At some point, you’ll find an interesting angle, one that reveals something you never noticed before. For example, (continuing the analogy) maybe from the orchestra pit you can see the many rows of stage curtains, the various levers, the intricacy of the lighting. You can see the pulleys and trap doors and secret stairs and other aspects that you couldn’t see from the other angles. Let that point of fascination draw you in; ride the wave of interest.

Curiosity does tap into the dopamine circuit, creating rewards for the activity. But apparently, according to researchers, it’s the anticipation that triggers the dopamine circuit, not the information reveal itself (Gruber et al, Kidd & Hayden). It’s the anticipation of the pending reveal from curiosity that delivers the rush; the high comes from being on the edge of discovering some new epiphany. You’ve seen something a thousand times before, but now a new thing is coming into focus; you can’t quite see it yet. It’s exhilarating, realizing that something new, unthought or unseen, is emerging. That’s when the dopamine hits! It’s like the weeks and months spent planning and anticipating an upcoming trip to a faraway place. On the actual trip, there’s less of a dopamine rush.

Conclusion

Curiosity is a powerful tool. Asking questions, becoming curious, following lines of inquiry — doing so can liberate us from agitated stages and rumination loops, but also, the same curiosity can unlock new ways of seeing for more artistic purposes.

Writing this essay has been more than an academic exercise. This approach to life has changed my general state of being. When I encounter some new information, I recognize my emotional state and become curious about it. I ask questions. Soon I become the actor who exits the stage and sits in the audience. That curiosity shifts my brain into Spock-mode, and unlocks new ways of seeing. The new ways of seeing often sidestep more stressful rumination and open up new perspectives.

To conclude, let me share a much-loved scene from the recent TV show Ted Lasso. In this scene, Rupert challenges Ted Lasso to a game of darts. In this scene, neither Rupert nor the viewers know that Ted Lasso spent his teenage years at a sports bar with his dad playing darts. Rupert’s lack of curiosity about why Ted would challenge him in darts leads to Ted Lasso providing a mini-lesson to Rupert, encouraging him to “be curious, not judgmental.” That phrase pretty much sums up my point here as well.

Works cited

Bernstein, A., Hadash, Y., Lichtash, Y., Tanay, G., Shepherd, K., & Fresco, D. M. (2015). Decentering and Related Constructs: A Critical Review and Metacognitive Processes Model. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 599-617.

Chang, E. Y. (2023). Prompting Large Language Models With the Socratic Method. Stanford University Computer Science. arXiv:2303.08769v2.

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of Curiosity Modulate Hippocampus-Dependent Learning via the Dopaminergic Circuit. Neuron, 84, 486-496.

Hill, K., & Freedman, D. (2025, August 8). Chatbots Can Go Into a Delusional Spiral. Here’s How It Happens. The New York Times.

Hilmerich, C., Hofmann, M. J., & Briesemeister, B. B. (2024). Anxiety and curiosity in hierarchical models of neural emotion processing—A mini review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 18:1384020.

Johnson, T. (2024, June 26). Seeing invisible details and avoiding predictable, conditioned thought. I’d Rather Be Writing.

Johnson, T. (2023, May 19). Book review of the Art of Noticing, by Rob Walker. I’d Rather Be Writing.

Kidd, C., & Hayden, B. Y. (2015). The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron, 88(3), 449-460.

Kitroeff, N. (Host), & Hill, K. (2025, December 31). She Fell in Love With ChatGPT: An Update. The New York Times, The Daily [Podcast].

Kitroeff, N. (Host), & Hill, K. (2025, September 16). Trapped in a ChatGPT Spiral. The New York Times, The Daily [Podcast].

Ted Lasso Season 1 — The Dart Game Scene. Be Curious, Not Judgmental. Apple TV+ [Video].

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.