What is Diátaxis and should you be using it with your documentation?

- Introduction

- What is Diátaxis?

- What does “Diátaxis” mean?

- Why follow the Diátaxis approach?

- Who is Daniele Procida?

- Comparing Diátaxis with other approaches

- Why is Diátaxis so popular?

- Breaking down the Diátaxis information patterns

- Objections about separating content by type

- Experiments at work

- Will information organization still be necessary when users interface with docs through AI tools?

- How can information patterns be used with AI prompting techniques?

- Conclusion

- Related resources

Introduction

One topic I keep seeing surface in various places online is Diátaxis. Here are a few places I’ve seen it surface:

- Upcoming webinars — see Introducing the Diátaxis Approach to Technical Documentation on the Content Wrangler’s BrightTALK

- PyCon talks — see What nobody tells you about documentation

- Reddit threads — see Diátaxis, a pragmatic system for technical documentation writing

- Tutorials that mention it — see API tutorials beyond OpenAPI

- Discussions among Python doc groups — see Adopting the Diátaxis framework for Python documentation, and more.

You can read more about it here: Diátaxis. It seems Diátaxis is gaining some traction in the technical writing community.

I knew Diátaxis involves organizing docs into four specific content types: explanation, reference, tutorials, and tasks. But I was fuzzy on most other specifics. The constant references to Diátaxis made me wonder, what am I missing? Is there something new here? Is this how I should be approaching the structure of my own documentation? And why is Diátaxis growing in popularity? What’s unique about the approach, and how does it differ from DITA?

What is Diátaxis?

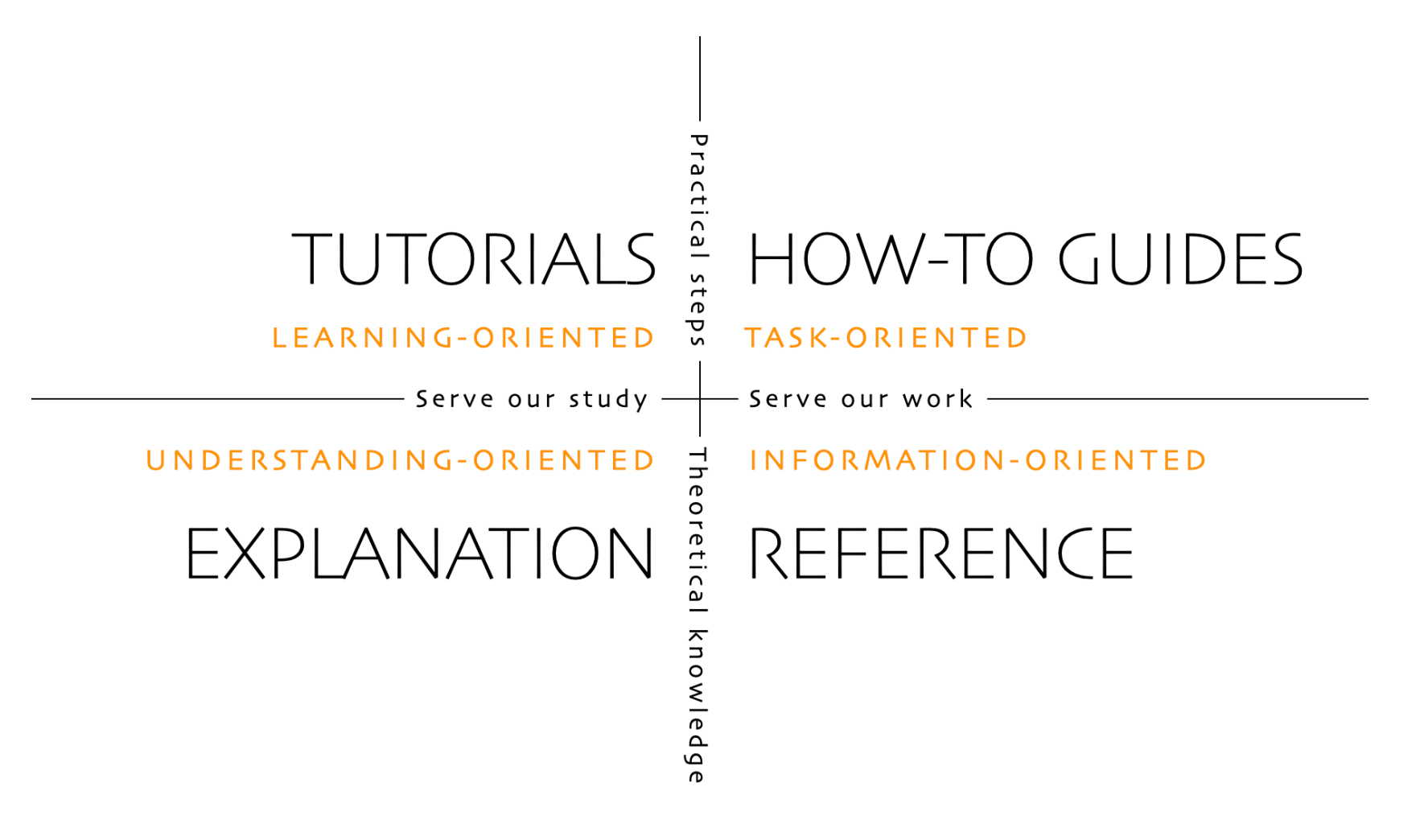

The Diátaxis approach divides documentation into four distinct content types:

- Tutorials - Lessons that provide a learning experience, taking users step-by-step through hands-on exercises to build skills and familiarity.

- How-To Guides - Practical guides focused on providing the steps to solve real-world problems.

- Reference - Technical descriptions and factual information about the system, APIs, parameters, etc.

- Explanation - Background information and conceptual discussions that provide context and illuminate topics more broadly.

The key premise of Diátaxis is that each content type serves a different user need and has a distinct purpose. Keeping them separated allows the content to be tailored and structured appropriately for that specific goal.

What does “Diátaxis” mean?

The name Diátaxis derives from Ancient Greek roots meaning “arrangement” or “layout.” It combines the Greek prefix dia, meaning “across”, with taxis, meaning “arrangement.”

This linguistic root relates to the organizational nature of the Diátaxis documentation approach. At its core, Diátaxis provides guidance for thoughtfully structuring documentation content into different categories based on user needs. The Diátaxis approach takes a jumble of disparate content and systematically arranges it into a meaningful, structured information architecture optimized around user goals.

Why follow the Diátaxis approach?

Here are some key benefits and promises of the Diátaxis approach:

- Helps users find what they need more easily since content is organized by their goals.

- Allows writers to focus on the type of content instead of wrestling with how to fit it into a less structured documentation system.

- Serves both beginners and experts more effectively by separating learning content from reference.

- Prevents muddling of content types, such as conceptual explanations in a how-to guide or instructions within a reference doc.

- Provides a consistent, structured model for organizing documentation across products.

- Promotes better quality content overall by keeping each type focused on its primary user need.

Who is Daniele Procida?

Daniele Procida developed the Diátaxis approach to documentation. Although he has a background in philosophy, Procida has been in the tech industry for a decade now, and has been involved in open-source software for even longer. He is currently an Engineering Director at Canonical.

Comparing Diátaxis with other approaches

As an approach for documentation, Diátaxis shares some similarities with other models.

How does Diátaxis compare with DITA?

DITA users will see quick comparisons with task, concept, and reference, but beyond these overlaps, DITA and Diátaxis actually have a lot of differences:

- DITA is a formal XML-based standard maintained by the OASIS standards organization. It consists of XML schemas that content must validate against. Diátaxis isn’t an XML schema and doesn’t require validation.

- DITA has a strong ecosystem of CMS tools and publishing systems built around its XML architecture. Diátaxis is not tied to specific tooling.

- DITA defines a few more core topic types than Diátaxis, including troubleshooting, glossary, and generic topics. Diátaxis focuses on just four main types: tutorial, how-to, reference, and explanation.

- DITA allows creating custom topic types through a specialization mechanism. Diátaxis doesn’t have extensibility for new types, as it’s not an XML schema.

- Diátaxis has a more prescriptive recommended information architecture based on inherent user needs. DITA is more agnostic about optimal structures. For example, you can assemble the tasks, concepts, and reference types into whatever arrangements you want.

- DITA emphasizes content reusability through topic-based authoring. The core idea is that componetizing information into these building blocks allows for efficient reuse across different deliverables (PDF, web, and more). Diátaxis isn’t concerned about content reusability and re-use across multiple outputs.

How does Diátaxis compare with Information Mapping?

DITA also shares some origins with Information Mapping, a technique developed by Robert Horn in the late 1960s. Although many details about Information Mapping are restricted by a paywall, here’s a brief comparison of Diátaxis and information mapping based on the information from Iva Cheung’s Introduction to Information Mapping post.

Cheung says Information Mapping identifies the following information types:

- procedure—e.g., instructions on how to do something

- process—e.g., description of how something works

- principle—e.g., description of a standard or a convention

- concept—e.g., description of a new idea or object

- structure—e.g., description of an object’s components

- fact—e.g., empirical information

You can see similarities here with other approaches. Diátaxis’ explanation is similar to principles and concepts. Reference might related to structure. How-to guides might relate to procedures and processes. I’m not sure what “fact” is, but perhaps it shares intent with tutorials.

Cheung says information management uses these three principles:

- Chunking: group information into small, manageable chunks.

- Relevance: limit each group or “unit of information” to a single topic, purpose, or idea.

- Labelling: give each unit of information a meaningful name.

Here Information Mapping seems more similar to DITA than Diátaxis, in that information is broken down into small chunks with single ideas. The labels, however, seem unique to Information Mapping and interestingly seem to share commonality with embedding techniques used when preparing information for LLMs.

How does Diátaxis compare to The Good Docs project?

Both the Diátaxis approach and The Good Docs Project are focused on identifying best practice patterns and templates for technical documentation, but they approach it differently.

Diátaxis defines 4 core content types — tutorial, how-to, reference, and explanation. In contrast, The Good Docs Project has developed a set of templates mapped to various technical doc types and needs, including:

- API quickstart

- API reference

- Code of conduct

- Explanation

- How-to

- Installation guide

- Logging

- Our Team template

- Overview

- Quickstart

- Style guide

- Release notes

- Troubleshooting

- Tutorial

While Diátaxis focuses on the high-level IA, Good Docs provides more tactical templates and writing guides tailored to each type.

Good Docs templates help authors avoid “blank page anxiety” and provide examples with embedded best practices. In contrast, Diátaxis provides more general principles to help guide what should go in each content type.

Why is Diátaxis so popular?

I believe Diataxis is gaining popularity in part because it reveals discernible information patterns within documentation. The approach defines distinct information types, which helps writers recognize structures for organizing content tailored to specific user goals. By defining various information patterns, the Diátaxis helps writers shape and organize content.

The concept of information patterns extends far beyond documentation. For example:

- Blog posts often follow story patterns.

- Academic papers have a standard IMRaD pattern (intro, methods, results, discussion).

- White papers use problem-solution patterns.

- Knowledge base articles need clear question-focused patterns.

- Speeches rely on patterns like the three-part list.

- Legal documents leverage definitions, clauses, sections.

- Marketing emails use subject lines, preview text, calls-to-action.

Seeing these patterns is like glimpsing the matrix behind communication. Understanding and applying patterns is at the core of rhetoric and document design.

The ability to identify and leverage information patterns in communication is central to the study of rhetoric. Rhetoric is often misunderstood as meaning language intended to manipulate or persuade. But its original definition is using language and information structuring techniques to fit a particular purpose, audience, or situation.

This is why so many technical communication academic programs are housed in rhetoric departments. The rhetorical tradition is fundamentally concerned with patterns of communication — how to shape content to achieve goals like persuading, informing, or motivating an audience.

Technical communicators are modern practitioners of rhetoric. Our job is fitting content to the expected discourse for optimal communication, comprehension, and usability.

Breaking down the Diátaxis information patterns

Let’s briefly look at the information patterns that Procida makes explicit. We’ll look at each information type and describe the salient characteristics.

Information patterns in tutorials

In the Diátaxis approach to documentation, a tutorial is “a lesson, safely in the hands of an instructor” that provides a guided, hands-on learning experience.

Whereas DITA focuses on tasks/procedures, tutorials have a different rhetorical shape tailored for education rather than solving problems. Some key elements of a tutorial pattern are as follows:

- Introduction/Learning goals - States what the user will accomplish in the tutorial.

- Prerequisites - Lists required knowledge/tools.

- Step-by-step instructions - Provides hands-on exercises and activities.

- Recap - Summarizes key lessons and takeaways.

- Assessment - Questions or exercises to check understanding.

- Next steps - Points to additional resources for more learning.

This clear rhetorical pattern serves the unique goal of building skills interactively. The lesson shape provides scaffolding and direction ideal for beginners.

(By the way, I’m not sure why “tutorials” isn’t an information type in DITA. The tutorial fills an important niche for learning content in technical communication. Maybe the DITA specification group felt that tasks include tutorials.)

Information patterns in explanation content

In Diátaxis, explanation content provides background and context to illuminate a concept. The goal is deeper understanding rather than problem solving. The following are some common elements of the explanation pattern:

- Introduction - States the purpose and previews the discussion.

- Definition - Formal definition of the concept.

- Background - Provides history and context.

- Details - Elaborates on various aspects of the concept.

- Visuals - Diagrams, illustrations, examples that clarify.

- Relationships - Connects concepts to other ideas and approaches.

- Implications - Explores effects, outcomes, and significance.

- Summary - Recaps the key points about the concept.

- Further Reading - Additional resources to learn more.

This rhetorical structure moves from overview to specifics in order to paint a rich picture of a topic. The goal is synthesizing disparate details into a cohesive narrative about the concept.

Information patterns in reference

In the Diátaxis approach, reference content follows its own distinct pattern serving a dedicated purpose. Procida states, “Reference guides are technical descriptions of the machinery and how to operate it.”

Whereas tutorials focus on learning, reference focuses on factual details about a product or system. Some hallmarks of the reference pattern are:

- Overviews - High-level summaries of a component’s purpose and capabilities.

- Specifications - Precise technical details of inputs, outputs, configurations, etc.

- Options - Charts comparing different options or versions.

- Parameters - Lists defining all available parameters and their usage.

- Code samples - Snippets demonstrating implementation and usage.

- Visuals - Diagrams illustrating technical concepts and relationships.

The reference pattern emphasizes comprehensive, accurate information presentation. The goal is precise and authoritative descriptions users can consult to understand the machinery while working with it.

Information patterns in how-to guides

In Diataxis, how-to guides follow a recipe-like shape focused on solving real-world problems. How-to guides help readers work their way through a problem-field.

Whereas reference provides technical details, how-to guides show practical application. For example, see this topic from the Django documentation: How to configure and use logging.

Some common elements of the how-to pattern include:

- Prerequisites - Required knowledge or conditions to solve the problem.

- Intro - If needed, a more detailed description of what the guide will cover.

- Ordered steps - Sequential instructions to solve the problem, to the extent that’s possible.

- Visuals - Diagrams and illustrations supporting the steps.

- Examples - Specific use cases demonstrating the problem and solution.

- Variations - How the steps may differ under certain conditions.

- Recap - Summary of what was accomplished.

- Related links - Pointers to other related procedures.

This structured pattern provides problem-solving assistance distinct from conceptual information. The goal is unambiguous guidance users can follow to solve a particular problem.

Objections about separating content by type

In learning about Diátaxis, I was concerned about the separation of content into distinct groups. Siloing documentation into tutorials, how-tos, reference, and explanation seemed overly opinionated and arbitrary as an information model. What research was this information model based on?

I reached out to Daniele on the #diataxis WTD Slack channel, and he clarified that Diátaxis isn’t meant to impose four rigid buckets that content must squeeze into. Rather, it’s an analytical approach that emerges from identifying four core user needs. In other words, when you identify the user’s information needs, these four fundamental types of documentation arise from those needs: tutorials, explanation, references, and how-to guides.

He acknowledges the critique that people don’t strictly separate these modes, but says that documentation itself should still be clear about its purpose and stabilize around meeting specific user needs.

So the core argument is:

- Users have different needs from docs.

- These needs can be mapped to 4 categories.

- If you write according to those needs, patterns will start to emerge, and …

- Thus, 4 types of documentation naturally form to serve those needs.

This model may oversimplify things, but the 4 Diataxis types are still useful as an abstract approach for thinking about docs, even if divisions aren’t absolute in practice.

Experiments at work

In my documentation at work, I recently separated out some concepts by type. For example, when working on reference materials for map data concepts, I initially had conceptual explanations scattered throughout the docs. This made it hard for users to find the conceptual information they needed.

So I decided to group all the conceptual topics into a central “Map Data Concepts” section — like a Wikipedia for map terms and concepts. This created a reliable one-stop shop for reference on key concepts. I now have a space to continue adding more concepts, and I don’t have to worry about reusing similar concepts in different API overviews.

Although I was initially reluctant to separate out concepts from the API overviews, this turned out to be a good move. Both conceptual definitions and overviews probably fit under “Explanation,” but even more granular separation of content by different explanation types seemed helpful.

Will information organization still be necessary when users interface with docs through AI tools?

At this point, note that I’m steering away from explanations of Diátaxis and introducing my own ideas.

With the rise of AI, I think the information architecture of help content may become less critical in the future. Most users will likely interface with documentation primarily through chatbots and other AI tools rather than navigating a complex help system. I wrote about this in AI chat interfaces could become the primary user interface to read documentation

In a way, this reduces the need to obsess over the perfect organizational schema. ChatGPT, Claude, and other AI agents can deliver hyper-personalized help on demand, without requiring the user to know where some piece of information lives in the docs. The AI interface essentially abstracts away the information architecture or pattern and just surfaces the most relevant content dynamically. This makes the documentation’s organization less important from a user perspective.

That said, the actual documentation source still needs to be well-structured for the AI to “learn” from it effectively. But the end user probably won’t care as much, if the AI delivers the right information to them directly.

How can information patterns be used with AI prompting techniques?

In the context of AI, there’s another major benefit to the Diátaxis information model. You can more easily create structured prompts that ask an AI to sort and arrange unstructured information into specific information patterns. I wrote about this in Use cases for AI: Arrange content into information type patterns.

Let’s say that you gather a large body of content about the Widget API from internal documents, code, threads, and more. You can then supply this corpus of unstructured content to an AI and ask it to arrange the relevant information into an information template like this:

{Intro}

{Prerequisites}

{Problem to solve}

{Ordered steps}

{Substeps}

{Examples}

{Expected outcome}

{Related links}

You could even include descriptions of each template section. The AI tool will then pick out the relevant information from the large body of material and arrange it into the pattern you defined. This can significantly speed time to a first draft.

Conclusion

In conclusion, should you be using Diátaxis? Even if you don’t separate content by type, defining and shaping content into these four content types might help improve your documentation. It’s an easy-to-understand approach to documentation that draws power and appeal from this simplicity. You can learn more at https://diataxis.fr.

Related resources

See this BrightTALK video Introducing the Diátaxis Approach to Technical Documentation.

I wrote this post with some AI assistance.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.