3.2 Techniques for deep work from Cal Newport

- Introduction

- The basic idea

- Definitions of deep and shallow work

- Why prioritize deep work

- Carving out sustained focus periods

- Routines

- Enemies to sustained focus

- Limits to focused work

Introduction

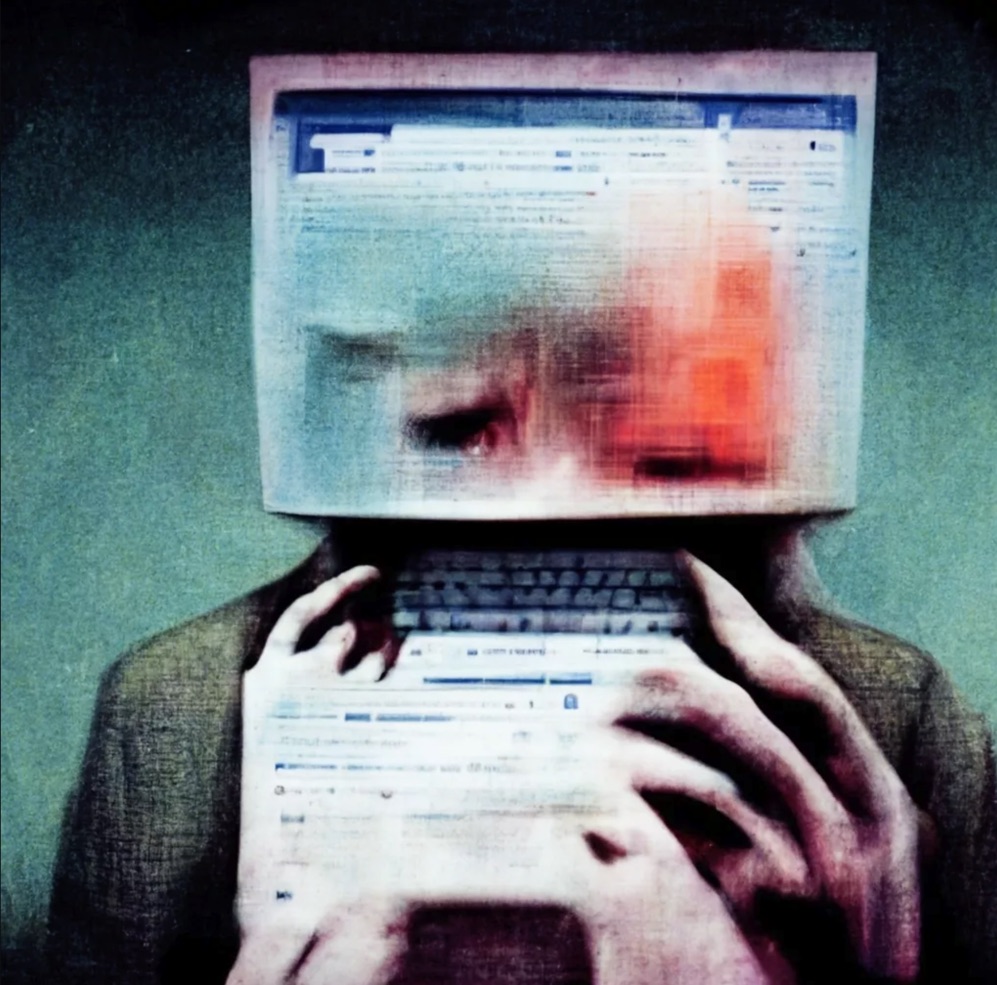

In the last article in this series, “From smartphones to Netflix: moving past plateaus in growth,” I explored how systems enforce constant rebalancing, so that if you make a change in one area that leads to a temporary gain, you might find that the system compensates in another area, eliminating your gains. Specifically, my abandonment of smartphones led to a temporary win with long-form concentration and reading, but it didn’t take long to find another form of distraction through television.

When I couldn’t identify the true source behind distraction (why do I keep watching TV?), I decided that maybe we point the finger too much at social media and other entertainment sites as the culprit behind our concentration failure. Long-form concentration is a difficult skill to develop. As such, I decided to read Cal Newport’s Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World (which is one of the best business books I’ve read and currently has 17k+ reviews on Amazon with a 4.5 star rating). The book lives up to the ratings: it describes techniques that unlock significant productivity. Fully implementing them, though, still remains a challenge.

The basic idea

I’ll summarize and comment on Newport’s ideas at length, but in case you want the short version, for me, it boils down to this: set aside several 90-minute focus sessions a day in which you block out distractions and focus on an important task. That’s it. If you can do this daily, you’ll be wildly productive. “Three to four hours a day, five days a week, of uninterrupted and carefully directed concentration, it turns out, can produce a lot of valuable output,” Newport says (16). It’s true. You’ll be amazed at how much you can accomplish during a few focus sessions like this.

Note that Newport has many nuances to my simplistic distillation here. For example, Newport mentions different working models, from the total hermit who disappears for days at a time to more of a journalist who disappears for a half hour here and there during other work. But the fundamental idea is the same: you need to dedicate periods of sustained focus on deep work to become productive.

Newport also spends a lot of time arguing for the value of deep work over shallow work, trying to convince the reader that deep work is more rewarding and satisfying than immersion in shallow activities.

Definitions of deep and shallow work

First, let’s start with some basic definitions. Newport defines deep work as follows:

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.” (3)

Notice that deep work pushes your cognitive capabilities, requiring focus and concentration. It’s usually not something you can do while watching Netflix from the corner of your screen.

In contrast, shallow work is as follows:

Shallow Work: Non-cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate. (6)

In distinguishing between deep work and shallow work, Newport says to use this test: consider whether the work could be done by a bright, young college graduate. Ask yourself, “How long would it take (in months) to train a smart recent college graduate with no specialized training in my field to complete this task?” (229). If the answer is that the college grad could learn to do this task within a few weeks of training, you’re not doing deep work.

Shallow work might involve tasks that you do on your phone, or tasks that involve social media consumption or even posting. If it’s something that a bright young college grad could do, with little training, it might be shallow work. This could even include putting together a slide presentation, Newport says.

Why prioritize deep work

Newport says that our natural tendency is toward easy, shallow work. We naturally follow the “principle of least resistance,” which means “we will tend toward behaviors that are easiest in the moment” (58). In fact, we often busy ourselves with tasks that make it seem like we’re doing a lot of work—responding to email, interacting in chat, attending meetings, doing little stuff, and so on—at the expense of a deeper focused state (74). This state of busyness is a mirage, however, and doesn’t lead to productive output.

Focusing on deep work yields a more satisfying, rewarding life. “A deep life is a good life,” Newport says (18). Deep work isn’t just a technique for productivity. It’s the key to a richer, more meaningful way of living. Newport says:

A workday driven by the shallow, from a neurological perspective, is likely to be a draining and upsetting day, even if most of the shallow things that capture your attention seem harmless or fun. …to increase the time you spend in a state of depth is to leverage the complex machinery of the human brain in a way that for several different neurological reasons maximizes the meaning and satisfaction you’ll associate with your working life. (82)

If we occupy our day with little meaningless tasks, checking our email obsessively, and doing small tasks that don’t require much thought or contemplation, we’re spending our time on frivolous errands that are the equivalent of junk food in a diet. Prefer more substance and you’ll feel the rewards of it.

At the extreme, focusing on deep work can lead to states of flow. Quoting psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Newport says, “The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile” (84).

Devoting yourself to tasks requiring deep, complex thought is more rewarding. In an ideal outcome, you might slip into states of flow (hyper-focus) where the external world fades away, you lose sense of time, and you become totally engrossed in your current activity.

Csikszenmihalyi focused his research on the theory of flow, which benefits our psychological well-being. Newport says, “…the feeling of going deep is in itself very rewarding. Our minds like this challenge, regardless of the subject. … the act of going deep orders the consciousness in a way that makes life worthwhile” (85).

Last weekend I spent most of my time cleaning and organizing our house while preparing for a birthday party. I didn’t spend much time writing or doing other deep tasks. At the end of the weekend, I felt like I’d spent my weekend time poorly. Sure, our bathroom drawers and closet were organized, and I’d watched a lot of sports (so maybe the downtime refreshed me), but I had a sense of not having accomplished anything. There wasn’t any deep satisfaction.

Newport also draws upon studies by Winifred Gallagher, who found that what people focus on most defines their state of happiness. Where you spend your time and thinking shapes your life. Newport says:

Our brains instead construct our worldview based on what we pay attention to.. …Gallagher’s theory, therefore, predicts that if you spend enough time in this state, your mind will understand your world as rich in meaning and importance. (77-79)

Gallagher’s “connection between attention and happiness” suggests that if you can focus your attention on deep tasks that matter, you’ll be happier (76). In contrast, if you focus most of your time on shallow tasks, your happiness level will be lower.

Overall, Newport tries to persuade readers that a deep life is time better spent. I think most of us will readily agree, but the question is more of a tactical one: how do you carve out time to focus in deep ways? The chaos of the world makes this hard, even seemingly impossible, to do.

Carving out sustained focus periods

Newport doesn’t force a one-size-fits-all model for deep work. He cites several possible working models for deep work. In the extreme, a person might retreat to a secluded cabin to work uninterrupted for days at a time. On the opposite end, a busy family man might escape for short blocks of time (such as 30 minutes) to work in a bedroom. In the middle of these extremes are the 90-minute focus sessions that I think fit me best. In part, this is because I want to gather momentum and flow for the writing task.

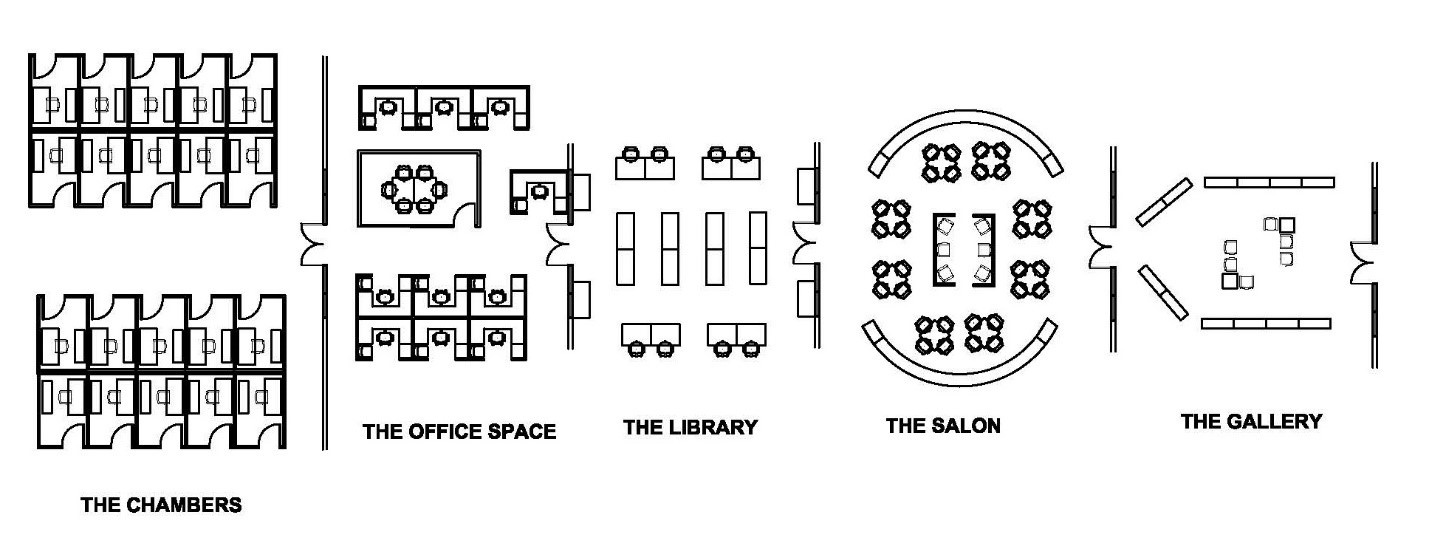

Newport says that David Dewane, an architecture professor, has a model of a Eudaimonia machine (Greek for “good spirit”) that involves rooms that progress from socially interactive at the outer layer to deeply immersive (like an inner sanctuary) at the inner level. The architecture begins with a gallery and proceeds to a salon, library, office space, and finally inner chambers.

Dewane’s model is for people to retreat for periods of time into the inner recesses of the building for deep, immersive thought, and then periodically surface back to the outer layers with more social interaction. Newport explains: “He imagines a process in which you spend ninety minutes inside, take a ninety-minute break, and repeat two or three times—at which point your brain will have achieved its limit of concentration for the day” (97).

Newport recommends that you find what works for you. “You must be careful to choose a philosophy that fits your specific circumstances, as a mismatch here can derail your deep work habit before it has a chance to solidify” (102). In fact, near the book’s end, Newport reveals that he follows more of the family man (“journalist mode”) who disappears for short stretches of time; he can’t simply withdraw from life for consecutive days or longer at a time like a hermit.

The 90-minute sessions resonate with me because I’ve found focus sessions to work well in the past. (I wrote about focus sessions earlier on my blog: idbwrtng.com/focussessions.) I use an app called “Focus” and previously followed a Pomodoro technique (more or less) of focusing for short periods of time. However, in my implementation of focus sessions, I developed some poor habits: anytime I wanted to stop, I simply paused the timer. Then I resumed it later. And I kept the sessions short, to either 20 minutes or 60 minutes. (For some reason, I’d stopped doing these focus sessions, and I can’t remember why.)

After reading Newport’s book, I decided to tweak the focus sessions a bit. Instead of pausing when I wanted a break, I tried not to hit pause. I’m not a monster, though. If my wife or kids needed me, or someone interrupted me with an information need, I would attend to it. I didn’t ignore everyone around me in off-putting ways. But I’d try not to break the session, especially not to check my email or do some other mental break such as checking the news or sports.

When you sit down and focus on a complex task, you must avoid distractions from email or the Internet. Even retrieving a small bit of information from the Internet, Newport warns, can lead to being sucked down a rabbit hole, as that’s what most Internet sites strive to do: hijack your attention. Put the internet, email, chat, and other disruptors on pause for a while.

It’s critical to reduce context-switching so that you can get more into a state of flow. The more you context-switch during the 90-minute session, the less effective it becomes. Newport says, “To produce at your peak level, you need to work for extended periods with full concentration on a single task free from distraction” (44). Don’t even glance at your email every 10 minutes because this creates context switching and carries over “attention residue.” For example, suppose you check your email during a focus session and find that an email gets you thinking about another topic. Even when you try to get back into your focus session, you’ll have some attention residue from the other context that dilutes your attention.

I’m also trying to train my brain’s muscles for longer periods of concentration. Newport says that even when people want to focus on a task, they often can’t because they’re so used to distractions. Newport says:

Unfortunately, when it comes to replacing distraction with focus, matters are not so simple. To understand why this is true let’s take a closer look at one of the main obstacles to going deep: the urge to turn your attention toward something more superficial. Most people recognize that this urge can complicate efforts to concentrate on hard things, but most underestimate its regularity and strength. … you can expect to be bombarded with the desire to do anything but work deeply throughout the day… (98-99)

So I recognize that my general inclination is to break up this 90-minute focus session and do something easier, such as glance at the news and my email. By resisting, I’m building up my ability to focus in a more sustained way. “The ability to concentrate intensely is a skill that must be trained,” Newport says (157). The brain is a muscle, and the more I can resist distraction, the stronger my long-form concentration power becomes.

Think of concentration as a brain muscle. You have to strengthen your concentration ability to get better at it. Our natural tendency is to stray off task and occupy our attention with easy things. Resist this tendency, and you’ll improve at immersion in deep work.

Routines

Another technique for carving sustained focus periods is to rely on routines. If you can build structures for your day that encourage deep work habits, you’ll be much more productive. Newport says, “The key to developing a deep work habit is to move beyond good intentions and add routines and rituals to your working life designed to minimize the amount of your limited willpower necessary to transition into and maintain a state of unbroken concentration” (100).

Establishing routines can help you stick with your plans for deep work. For example, follow a similar structure at the same hour of the day. Maybe complement your rituals with a specific beverage.

These routines and rituals kick in when your willpower drops. Matthew Crawford also mentions rituals in The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction. Crawford encourages people to establish structures—metaphorical “jigs”—that naturally guide people into the right actions. Crawford explains: “A jig is a device or procedure that guides a repeated action by constraining the environment in such a way as to make the action go smooth, the same each time, without his having to think about it” (31). For example, when carpenters need to create multiple pieces of wood with the same dimensions, they’ll create a prototype that becomes the model for cutting the others rather than re-measuring and cutting each piece individually. If you can create jigs in your environment that naturally build into the routines you want to keep, you’ll stick with them.

These focus sessions can’t be a one-off activity every other day. Newport says that rituals are important because your success depends on your ability “to go deep, again and again” (119). That’s where structure becomes important, as it helps transition the activity into a daily habit.

For me, writing during the first hour of the day works best. I often wake up earlier than others (kids and wife are still asleep), so this time of day has fewer distractions. Further, as I get older, I’ve noticed that my brain works best when it’s fresh, during the first hours of the day.

As the afternoon and evening set in, my brain gets more tired and I have less energy for mentally consuming tasks such as writing. Therefore, if I can get in 1-2 hours of writing in the morning, and then save the later hours of the day for editing or other less cognitively demanding tasks, I’m more productive. By the time evening rolls around, I mostly edit what I wrote earlier.

Enemies to sustained focus

Fitting in periods of sustained focus can be especially difficult in a corporate culture, where you’re expected to respond to chat and email continuously, Newport says. If you disconnect at work, people will likely think you’re not working. But if you open yourself up to constant disruption, you’ll become entrapped in shallow activities all day.

Figuring out the tactics of deep work can be more challenging than the idea itself. For me, when I have several thirty-minute meetings punctuating the day, it can be difficult to focus deeply. First, I usually have to prepare for meetings, which means coming up with agenda topics. After the meeting, I’m emotionally depleted, so I need some recovery time. I also want to type up the notes and send them out, then create tickets for any action items. A thirty-minute meeting, therefore, takes at least an hour. Add lunch to three meetings, and my actual time is much less. If I look at the clock and see that my next meeting is in 20 minutes, it discourages me from jumping into a 90-minute focus session.

To get in several 90-minute focus sessions during a workday, I might need to adjust my schedule a bit. For example, I could try to adjust my meetings so that they’re all back-to-back, which would allow for more sustained focus periods. Or I could shorten the focus sessions. But at work, I don’t often have the luxury of changing meetings.

In short, carving out several 90-minute sessions a day isn’t easy. It might involve ignoring colleagues and product teams for chunks of time, which could seem off-putting in a “ubiquitous culture of connectivity, where one is expected to read and respond to emails (and related communication) quickly” (56).

Constant distractions in an open-office, always-connected corporate culture can be an enemy of deep work. The paradox of this culture is that it leads to less productivity, not more, Newport says.

The offline behaviors that might seem like you’re not working (why hasn’t Tom responded to my chat message?) are the exact behaviors that lead to greater productivity. If it takes you 90 minutes to respond to your manager’s email, it might give the impression that you’re “away” from your desk during work time, maybe running personal errands or going on leisurely walks. Hardly! During this time, you might actually spend the necessary time to get that complex documentation written.

At my work, there’s a common practice of writing “manuals” about themselves. I created a lengthy guide that explains my styles and preferences, including the fact that I have most notifications turned off and so might not respond immediately to chat or email because I prefer deep focus. But even if people don’t read my user manual (I don’t expect them to), they will appreciate increased documentation output in exchange for slower communication.

Part of the problem, Newport explains, is that knowledge workers have unclear productivity metrics. It’s not easy to measure output, so the person who appears busy (by being visible online) might actually be the least productive. Academic work measures productivity through the number of peer-reviewed articles published each year. As a technical writer, measuring articles published (or more granularly, word count) with documentation is much more challenging. For example, I could tell you the number of lines changed in code commits I’ve submitted, but the auto-generated Javadoc I imported several times will drastically distort these metrics. Publishing content written by someone else could likewise distort metrics. It’s much more time-consuming to author content from scratch than to lightly edit and publish something engineers wrote. But someone could equally argue that it’s better to crowdsource the docs anyway, having product teams do their own writing. It’s also challenging to measure the output of management tasks like distilling tickets into concrete, actionable tasks for others to tackle.

Even with these difficulties, I have noticed that if I can squeeze in several 90-minute focus sessions, I am massively productive. The difference is noticeable. Honestly, I wrote the bulk of this content in one such session. The other week at work I had a complex documentation task that involved describing some new and confusing attributes added to an API. I’d been meaning to get to these attributes for more than a week but couldn’t make progress. One day I sat down for two hours and completed a first draft. That first draft (where you create something from nothing) is the most mentally taxing, but the subsequent edits are much less demanding.

Here’s the secret: If you can complete three of these 90-minute sessions a day, you’ll be so productive that you will finish your work earlier than you anticipated. A good focus session might wrap up the work entirely! Especially if I’m operating during my peak performance hours (early in the morning), I can make more progress on writing projects.

Limits to focused work

Working on the doc projects in 90-minute sessions, after I cranked out the description of those complex attributes, my brain hurt. I could feel my mental wheels were being taxed. That’s a good sign that I was actually engaged in deep work: I could feel the muscles in my brain being worked over, like I’d just gone to the gym.

Newport says most people can’t sustain focused concentration for more than 1-2 hours a day. Even the most experienced professionals tap out at 4 hours. Newport writes, “The most adept deep thinker cannot spend more than four of these hours in a state of true depth” (220).

I agree with this limit, which aligns with my general writing method for this blog over the years. I typically spend an hour writing a post in the morning or so. If I can space out the writing to 1-2 hours a day over a week, I can make a lot of progress. With writing (whether blog posts, documentation, or books), it’s hard to sustain an active writing effort in any genre for more than 4 hours, especially if you’re generating original material. (This is why it pains me to see my children procrastinate essays right before the deadline—I know they probably can’t sustain a long marathon writing session, especially after midnight.)

Newport says “once you’ve hit your deep work limit in a given day, you’ll experience diminishing rewards if you try to cram in more. Shallow work, therefore, doesn’t become dangerous until after you add enough to begin to crowd out your bounded deep efforts for the day” (220). In other words, Newport isn’t against shallow work; he just says to prioritize deep work first in your day, then once you’ve hit your limit, cycle in the shallow work. In my experience, editing existing writing (improving sentence flow, removing typos, and other proofreading) fits into the shallow work category. In contrast, generating the first draft of anything requires deep work.

I was still developing my ability to work focused for 90 minutes at a time. It was challenging. One morning, I tapped out at 60 minutes and wandered into my garage to organize my tools (not something I usually do). I completed just two 90-minute sessions during a light meeting day, despite my goal of three. Meetings could make it nearly impossible, but even without meetings, my brain isn’t used to sustained focus for 90 minutes (with no breaks to check email or browse Internet sites). I hoped a longer focus period, however, would lend itself to more periods of flow.

Newport devotes a lot of the book to enemies of distraction. Chief among these are social media and email. I’ve purposely downplayed the treatment of social media in my summary here because, in my view, we tend to want a scapegoat for our inability to concentrate. In exaggerated ways, social media becomes that scapegoat.

It is certainly true that social media could interrupt my ability to focus and temporarily short-circuit the wiring in my brain. But based on my experiences, especially how I knocked out the lengthy documentation project in a matter of weeks, I felt that the real key to productivity was not so much to abandon the smartphone but rather to devote 90-minute distraction-free sessions during the day. If I could accomplish these focus sessions, what I did outside of those focus blocks, even if it involved interacting with social media, didn’t seem too harmful to me. Newport did caution: “Spend enough time in a state of frenetic shallowness and you permanently reduce your capacity to perform deep work” (7). Again, I didn’t think social media permanently rewired our brains. But it might take some re-training to break free of the constant scrolling and skimming habits.

Newport says that in a world increasingly consumed with shallow work, those who can focus on deep work possess a highly valuable skill. The larger hypothesis of his book is that “The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time as it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive” (14). Most of us will agree that devoting several sessions of deep focus (whether 90 minutes or another time period) will lead to significant productivity gains. The challenge is finding the right tactics and techniques to make those focus sessions a reality.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.