1.8 Random notes on recovering the lost art of reading

- Queuing up books?

- Buy print versions of audiobooks I enjoy?

- Returning or borrowing books?

- Could I hate and love the same book?

- Paperback or hardcover?

- Used or new?

- Is reading expensive?

- Is reading passive?

- Writing as a conversation the authors were having about the books they read?

- Were book clubs worth joining or starting?

- How do I remember words I look up?

- Real purpose of reading is to spur intellectual engines?

- Modular reading versus single-book reading?

- Could I skip ahead when bored?

- How to control my saccades?

- What aspects of technology discouraged long-form reading?

- What value did non-technical books have on a technical career?

- What about books related to tech comm?

Queuing up books?

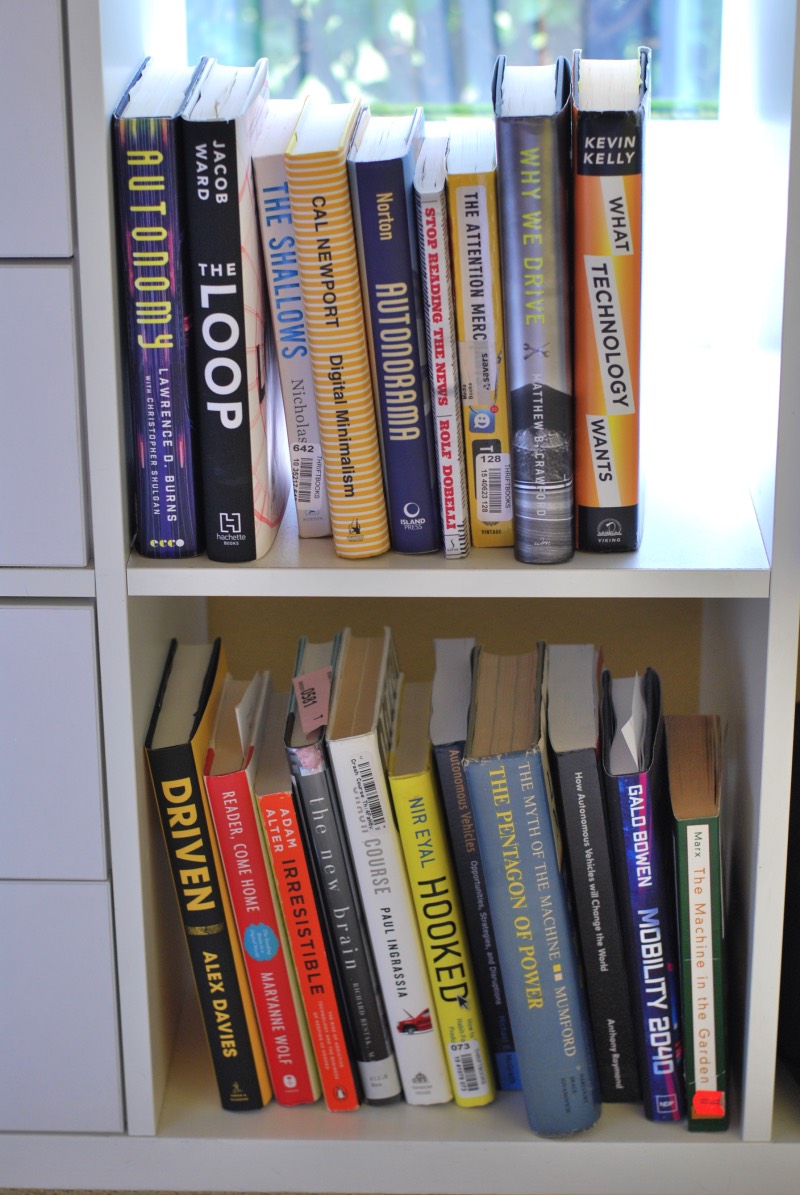

When I began the “Book a Week” challenge at work, I came across a page of tips that said to collect a pile of books that you plan to read over the year ahead of time. Otherwise, when you finish one book, you might lose your reading momentum for the next one. Ordering a hardcover or paperback through the mail often took a couple of weeks to arrive. So as I ordered them to queue the books up, I soon had a whole shelf of books waiting to be read.

The problem was that my interests evolved from book to book. I started out reading with a question about how technology affects our attention span and focus, and I also read books related to the auto industry and driving. But sometimes a book ignited or prompted other questions, which then shifted my thinking and interests. For example, I wasn’t so eager to continue reading about how smartphones affect the brain, as I felt I’d read enough material tackling that question (Shallows, Stolen Focus, Digital Minimalism). I still had a few books queued up on that topic (such as Hooked and Irresistible), but I never got to them. My interests shifted to more philosophy-like topics.

Ordering books was a bit of a gamble as well. Some books turned out to be duds. For example, I started Reader, Come Home but found that after the first 15 pages, I wasn’t really interested. Same with The Loop. I tried to like that book, but after 150 pages, I decided it wasn’t worth slogging through. Given the possibility of duds, I decided that having a shelf full of unread books wasn’t such a bad idea.

Buy print versions of audiobooks I enjoy?

Some books on my “To Read” shelf were print versions of audiobooks that I immensely enjoyed, which prompted me to order the print copy. But after finishing the audio version, I wasn’t inspired to revisit it in print. Namely, The Attention Merchants, Digital Minimalism, and Crash Course. Even so, I wanted the print version so that I could easily reference some passages, perhaps. Yet so far, after I finished a book, I mostly moved on to something else. Maybe I just wanted a visible artifact to remind me of the book?

Returning or borrowing books?

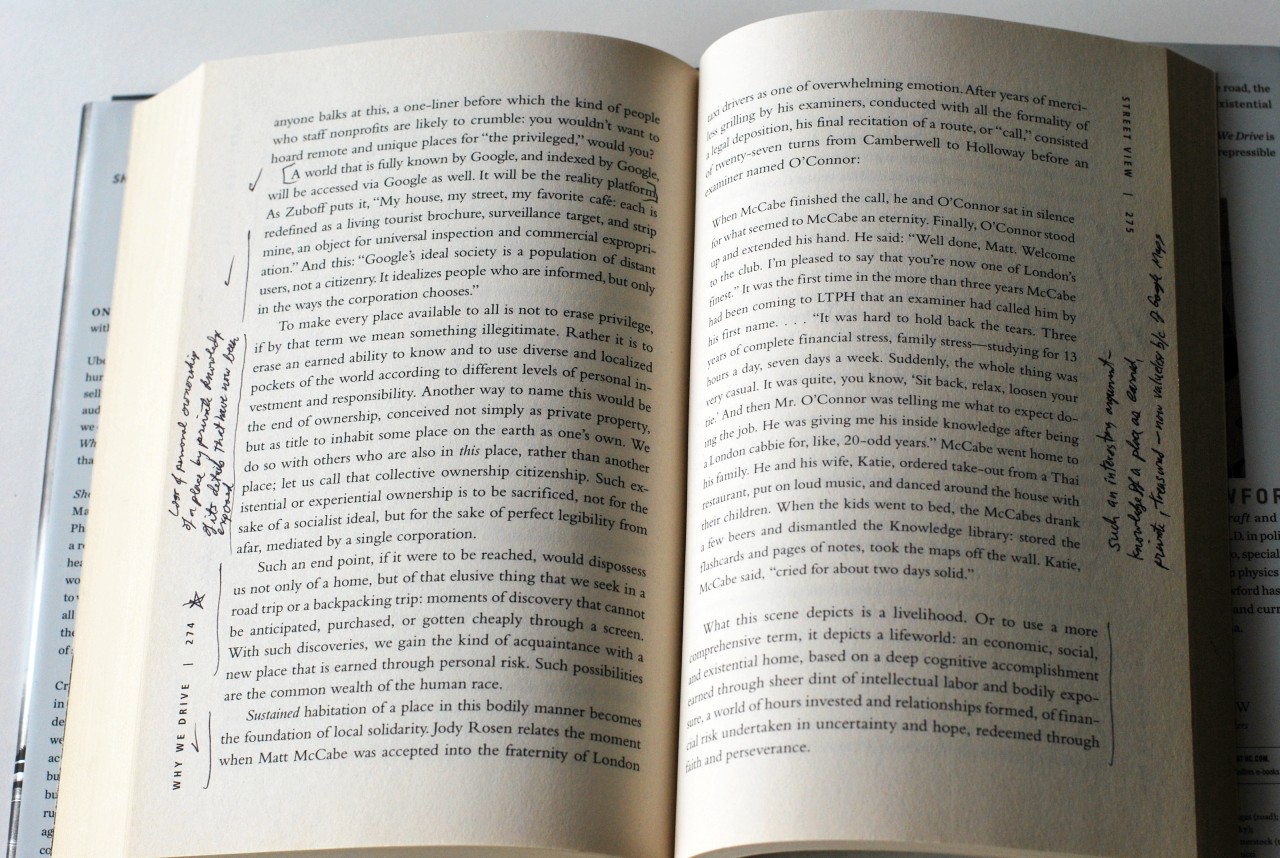

I enjoyed writing notes in the margins of all the books I read. Sometimes my notes were high-level summaries of the author’s main point in that section, which maybe just crystallized in my head. I also noted passages and paragraphs I liked. Sometimes I underlined the passages, but mostly I just bracketed them and put checkmarks in the margins. If it was a passage I really connected with, I would draw a star. Multiple stars if I really liked it.

For me, part of the reading experience involved interacting with the book through these annotations. Writing in a book destroyed it for resale, but I considered that part of the cost of reading.

Could I hate and love the same book?

Even if I liked a book, not all of its chapters usually resonated with me. After I finished Matthew Crawford’s Why We Drive, I felt the book had many ups and downs. Sometimes I struggled to follow the author’s point and it seemed like random anecdotes that didn’t support the larger theme. Other times, I had stars everywhere and many checkmarks. In other words, it was a rollercoaster of loving and hating the book for the whole 318 pages. Was that normal?

In the end, though, my likes outweighed my dislikes. I loved his balance of personal experiences and philosophical ideas. Crawford dropped enough philosophy to be interesting but peppered it with personal experiences to create a sense of authenticity and immediacy (akin to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance). When I tried reading philosophers who omitted the personal element, I found the content too dry. (I mean, can anyone enjoy reading Heidegger in the same way you enjoy Kerouac?) Overall, I realized Crawford’s approach was my favorite style: balancing personal experience with ideas. Learning should involve some transformation or commentary related to your life, I felt.

Paperback or hardcover?

I preferred hardcover because it traveled better. I would frequently stuff the books into my bike pannier or other bags as I carried them around. Paperbacks could easily be folded or otherwise mangled. And surprisingly, used hardcovers tended to be cheaper than paperbacks (especially for popular books, of which there’s a surplus). I disliked Kindle entirely. Reading from screens wasn’t my thing.

Used or new?

I preferred used books. The less expensive, the better. (That way, if the book was a dud, I wouldn’t have blown too much money.) I didn’t mind if there was writing from the previous author—it was kind of interesting to see what parts resonated with other readers. Seeing the annotations (systematically applied) let me see how others marked up books. I added my own annotations according to my style anyway, so the different annotations didn’t confuse me. Sometimes, it was clear when readers stopped reading the book, as their annotations ceased.

Is reading expensive?

Even though I had a shelf of books, the cost was relatively cheap. I considered how much it costs to eat at a restaurant or go to the movies for just one day of entertainment. On the other hand, if you spent $100 on used books, I reasoned, you would have at least 1-2 months of entertainment right there. For the same cost as a latte or two, you might spend an entire week reading a book. And if I were broke, I could still borrow books from the library and resort to post-it notes as a form of annotation for a completely free experience.

I was fortunate that both my main hobbies, reading and writing, didn’t require much money (just infinite time). It wasn’t like being a car collector or an RV recreationist.

Is reading passive?

Reading did feel a bit passive to me. How does one engage with the ideas in a book, I wondered? Did you drink them in and then continue on about your life (slowly forgetting them)? Did you wrestle with the ideas in book reviews and other blog posts? Did you allow the book to naturally shift your world perspective? How did you switch from being a passive reader to a more interactive information consumer?

Writing book reviews seemed like an appropriate practice for more active reading, but book reviews by themselves weren’t that engaging of a format. You could get a book review and snippets of impressions about the book from pretty much anywhere, especially from dozens of readers on Amazon, so what was the value of posting a review on my blog?

I liked picking out the author’s larger argument as I read through their book. Sometimes the argument was murky at first and not clear how all the sections connected into a coherent argument. But learning to look for this larger argument helped me be a diligent reader. That’s partly why I wrote more notes and idea summaries in the margins—I was looking to more clearly grasp the larger idea and reasoning that supported the author’s assertions (probably a leftover habit from my composition teaching days).

Writing a post that articulated the author’s argument also took a lot of effort. Synthesizing the author’s main argument, assessing their support, and writing a review required a lot of literary prowess and erudition, especially to contextualize the author within a larger landscape of similarly themed books. It wasn’t a genre I was skilled at given my limited awareness of the genres I was reading.

Writing as a conversation the authors were having about the books they read?

Much of writing, I noticed, involved a conversation the author was having with other sources. I liked thinking of writing as a conversation. Writing was the way the author interacted with what he or she was reading, either using the sources to support an argument, or calling them out to refute gaps or other errors of thinking, or connecting them with personal experiences and elaborations. Thinking of writing as conversation seemed to unlock a technique for content generation.

Almost every good book I’d read seemed to involve the author summarizing and responding to a variety of sources. When the sources were absent, the writing was usually narrow-minded. Reading was a natural precursor, even a requirement, to writing.

That said, I was overwhelmed by how much writers actually read. From the looks of the sources and books cited, it appeared as if the writers had read tomes on the subject they were writing about. Were they sampling only the relevant chapters in these books, or had they devoted multiple years to absorbing everything in a niche? And how did they keep all the quotations and references organized?

No doubt tools like Google Scholar helped them locate a network of relevant texts about a subject. Even so, I needed to figure out a system for storing quotations and summaries of books (my method for a “commonplace book”) so that I could reference the quotations later in posts. I tried using Foam (a personal knowledge management tool) for storing quotes, which included backlink functionality based on topic keywords, but the method didn’t stick.

Were book clubs worth joining or starting?

If I didn’t write book reviews, what substitute activities could be worth pursuing instead? Book clubs? I’d been reading books related to the auto industry as a way to increase my interest and knowledge of the domain I worked in (maps in cars). Because I discovered some really interesting books (Autonomy, Autonorama, Why We Drive, Ludicrous [Tesla], Crash Course, Mobility 2040, The Geography of Nowhere, and more), I wondered if perhaps I should start a book club at my workplace for this niche. Or perhaps including book summaries and commentary in org newsletters could work? I couldn’t quite figure out what to do with the knowledge from books.

Many months later I actually started a book club at work, called the Auto & Transportation Book Club. It turned out to be surprisingly successful, though it depends on how success is defined. If measured by the value of the discussions, then the success was 10/10. If measured by the number of participants, which ranged from 4-8 on average, then the success was 2/10. Even so, my idea to foster a “workplace literary salon” with invigorating and broadening conversations was probably too idealistic for a corporate environment where everyone had their own objectives and key results (OKRs) to answer for.

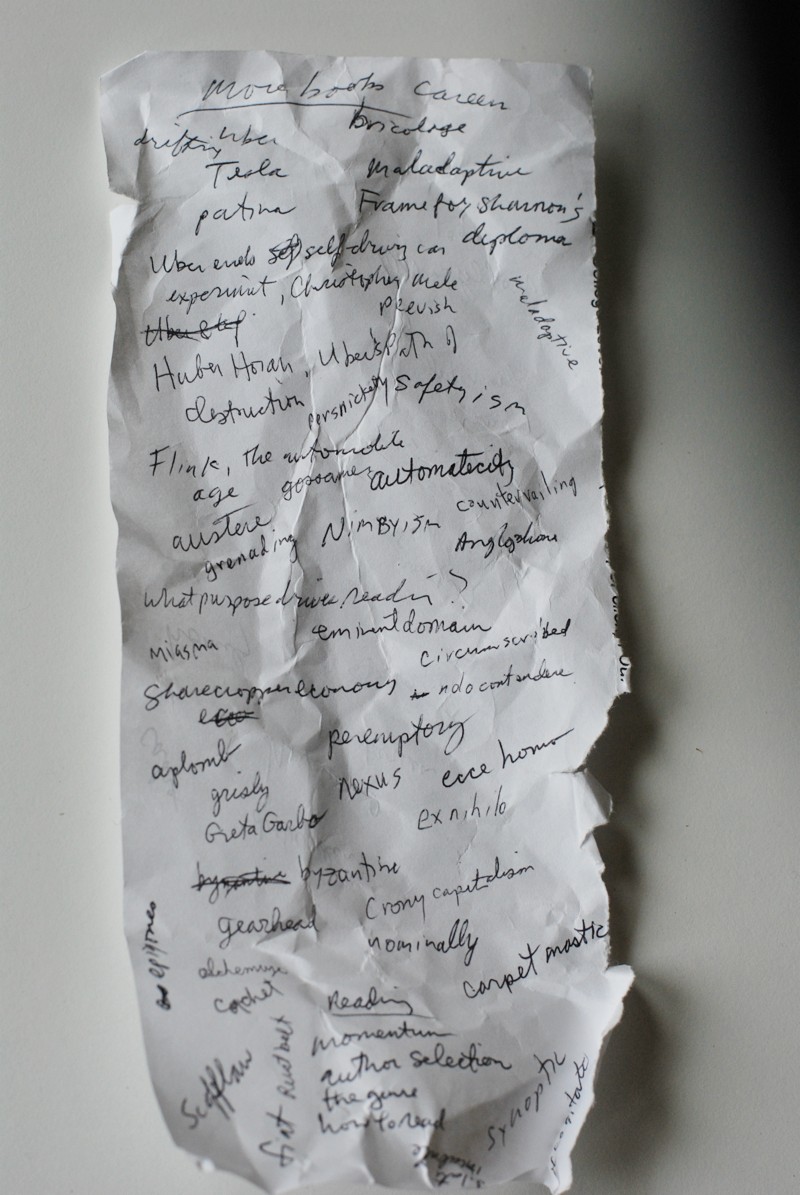

How do I remember words I look up?

Years of being a technical writer had taught me to prefer simple, easily understood words. As a result, I let my vocabulary stagnate. As I read more books, I noted unfamiliar or interesting words on a piece of bookmark paper as I was reading, along with other random notes.

Then eventually, as I grew tired of reading, I’d take an hour or so to look up the words. A few times, I actually paired the vocabulary words with their image equivalents (pulled from an online image search) to cement pictures with words. Looking for supporting images turned out to be fun and helped me remember the words better (such as “anarcho-primitivist”). If language provided the tools for expression, then I felt that increasing the number of tools at my disposal would certainly help me be more articulate.

Real purpose of reading is to spur intellectual engines?

Even if I didn’t engage with a book by writing about it or discussing it in a book club, I figured reading by itself would spur more “intellectual vibrations,” as Nicholas Carr described them. Reading helped prime and warm up my intellectual engine (unfortunately not a V-8), which then made me more capable of performing other tasks, including writing documentation. In this way, reading was like a way to start the day, warming up before practice or a game.

Modular reading versus single-book reading?

Was it better to read modularly/horizontally across authors and sources to follow a theme, such as individual essays or chapters from various sources, or to read a long book from start to finish? Reading modularly, such as chapters from the O’Reilly Books library or standalone journal articles, offered more direct access to a theme, while reading entire books from start to finish allowed for more random discovery of ideas and deeper immersion. Reading a book end to end, I got to know the author’s way of thinking on a more intimate level. And across the length of a book, I stumbled upon themes and ideas that I wasn’t searching for. It was more satisfying to make my way through an entire book. When I finished, it felt more gratifying than if I had sampled a theme from many different sources.

However, sometimes books shifted focus. For example, in Stolen Focus, the author steered the theme from distraction due to technology into distraction due to ADHD, abuse, nutrition, pollution, and other angles. Was it in the service of padding for page count, or was the author digging deep? Did books really need 200 to 300 pages to convey their argument and core facts? Couldn’t that be done more efficiently in a single article? And if I needed a variety of sources to quote from, variety might be better in the long run. And yet, reading a single article wasn’t nearly as enjoyable as an entire book.

Could I skip ahead when bored?

Sometimes while reading, a chapter bored me. I wondered if I should skip ahead, or whether I should instead slog my way through the boring parts? Skipping ahead could help me continue with the book instead of abandoning it altogether. Too many uninteresting chapters in a row and I would toss the book aside. But maybe, I thought, the book would slowly come alive in the chapters that I decided to skip. Later chapters might not make sense if I skipped earlier ones. It was hard to tell.

How to control my saccades?

“Saccades” refer to your eye movements as you track across lines and sentences while reading (or tracking other things). Our saccades aren’t smooth, sweeping motions from left to right across the page. Instead, our saccades involve little uneven jerks of rapid movement. When I was searching and assessing information (or consuming information from feeds), my saccades were quick, tracking the F pattern that UX researchers described as I tore through the linguistic shape and high-level substance of a page in 15 seconds.

But when I was reading a book with worthwhile information, I slowed my saccades way down, almost like I was in slow motion. Otherwise, I would miss the meaning. Did this make me a “slow reader”? Perhaps. But not all content could be consumed at the same pace. Reading a fast-moving fiction novel required a much different pace than absorbing complex philosophical ideas. The ability to slow down my saccades helped increase my concentration and focus.

What aspects of technology discouraged long-form reading?

How did I get out of the practice of reading in the first place, I wondered? As a student, many books I read were assigned, while those that I discovered on my own had more personal reward for me. Even so, at some point in my career, I realized that to get ahead as a technical writer, I needed to expand my technical knowledge (for example, learn Java). Given that I had only so much bandwidth, I tried to confine my selection of books to technical books, to learning programming or other more career-useful information. I told myself that to thrive in an increasingly specialized career year after year, I needed to become more technical. Being technical was the key attribute that would allow me to thrive as a technical writer.

Yet I confess that more technical books on programming and engineering-related topics never interested me in a sustained way. I was much more interested in non-fiction literature, the kind I studied in my graduate MFA program. Crawford’s Why We Drive was the perfect balance of ideas and personal experience, which was the type of content I’d longed to write myself on my blog over the years. I speculated that perhaps I stopped reading because I was mentally trapped in a programming genre that I found suffocating. As I branched out, it was like opening a window and breathing in fresh air. Maybe I started reading in part because I no longer confined myself to strictly technical books?

What value did non-technical books have on a technical career?

What value did non-technical books have for a technical career? Much of the work of technical writing, at least at this point in my career, didn’t consist of individual study of APIs and code, as odd as that sounds. Much of the work in tech comm involved interviewing engineers and reviewing existing content. Sure, you looked at code and needed some level of technical proficiency, but there were diminishing returns. To climb up to the level of competency to understand code independently, you would need to almost be a programmer yourself. And the more technical knowledge you immersed yourself in, the more the gaps would develop in other areas, such as with review methodology, project management, information architecture, and last but not least, the business domain itself.

Also, ironically, I found that as a “tech lead,” my role evolved to include more strategy and planning than actual writing. My role as tech lead wasn’t so much to write more technical docs but to identify friction areas, convert those frictions into concrete and achievable tasks, prioritize the work against partner needs and upcoming releases from product teams, assign the tickets to other writers, and streamline our publishing processes. There was much less of a need to know how to read and execute code.

In short, the higher I climbed in job levels, the more my work shifted to content strategy rather than tactics. I no longer needed to be down-in-the-weeds technical. I needed to simplify complex information, but reading a book on Java wouldn’t really help. The tasks were more ambiguous rather than technical. I started to wonder if I had overestimated the need for deep technical knowledge in my career. This opened the gates for more aggressive reading outside the technical domains.

What about books related to tech comm?

In reading several auto-related books, I began to question how this specialized domain knowledge would benefit me in the long run, especially if I decided, after a few years, to switch domains. Shouldn’t I be reading books about tech comm, I thought? Unfortunately, tech comm books tended to be boring, and in some ways, tech comm was meant to support more knowledge-specific domains anyway. There is a difference between studying knowledge domains (such as the auto industry) and communication methods (such as rhetoric). With communication methods, the focus was on decisions and patterns for communicating information, not specific to any particular product. The study of those communication patterns themselves was sometimes interesting, and obviously I have a blog about technical writing. But books on tech comm never ignited my curiosity, for some reason. There were a few exceptions, such as Every Page Is Page One, where the author followed a bold idea with interesting analyses. But it was more fun to become immersed in a specific knowledge domain, such as learning about cars. I never found a tech comm book written in a style like Matthew Crawford’s Why We Drive.

At any rate, despite the many unanswered questions, these were the observations I’ve had about reading these past few weeks. Reading opened up a plethora of questions about reading itself that I hadn’t considered.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.