3.5 From monkey mind to calm, ordered consciousness -- even outside of flow? Wrestling with Csikszentmihalyi's assumptions about psychic entropy

- Context and background for this topic

- Why accept the monkey mind as a natural state?

- Csikszentmihalyi on pre-conscious states

- How humans developed consciousness

- Origins of consciousness—the bicameral mind hypothesis {#origins-of-consciousness—the-bicameral-mind-hypothesis}

- Metaphoric language and consciousness

- Externalizing thought through writing

- The first time I became aware of consciousness

- Paradoxes of consciousness

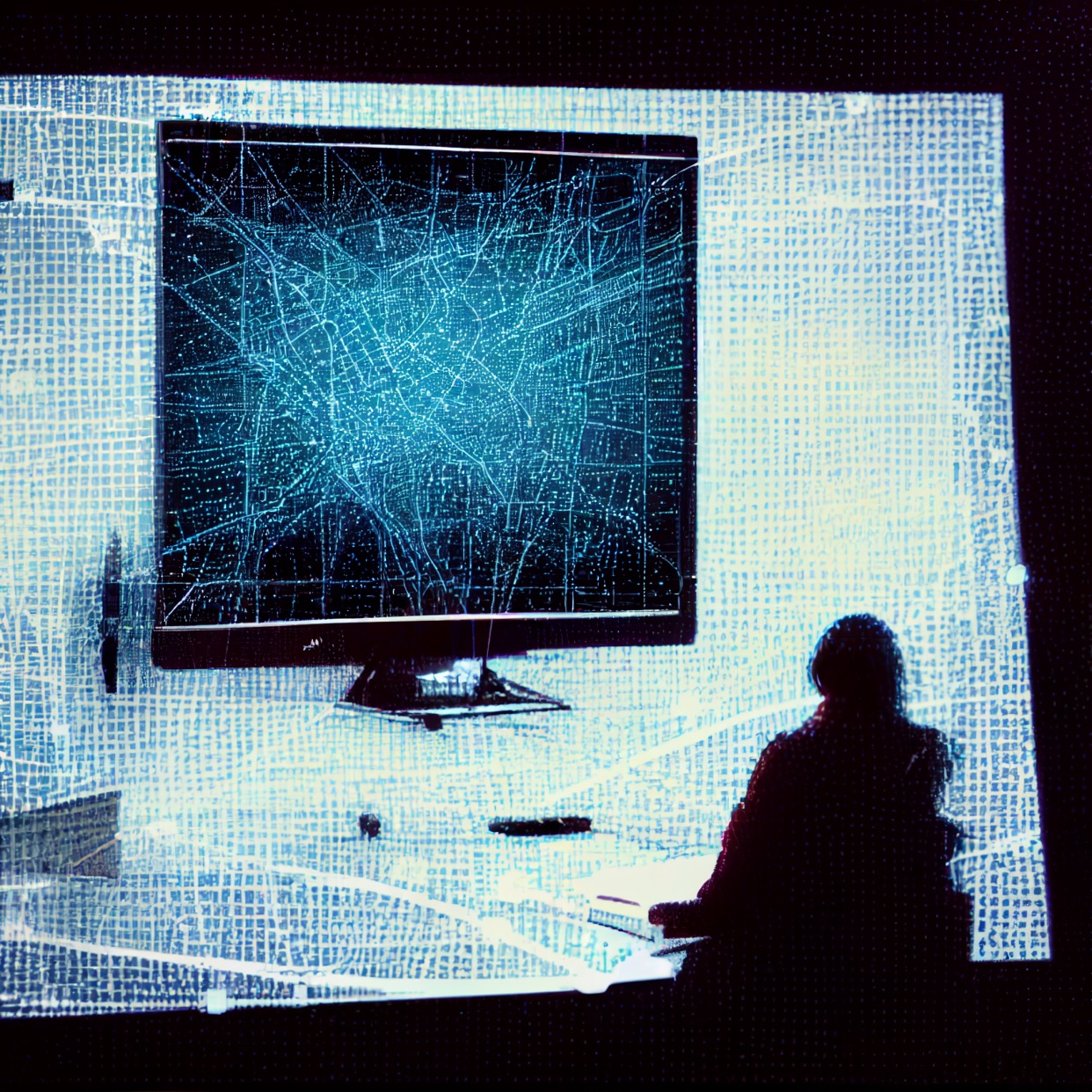

- When consciousness trends toward the dark side

- Internalizing a 19-second pattern

- What I’ve noticed {#what-i’ve-noticed}

Context and background for this topic

In my last post, “Applying Csikszentmihalyi’s psychology of flow,” I explained that Csikszentmihalyi says our normal psychological state is one of constant entropy (disordered, unstructured thought). Some people call this “monkey mind,” a term coined by Buddha to refer to the way a monkey swings from branch to branch, similar to our mind jumping from thought to thought.

The whole point of getting into flow, according to Csikszentmihalyi, is to counter that entropy with a more “ordered consciousness.” Csikszentmihalyi says,

The optimal state of inner experience is one in which there is order in consciousness. This happens when psychic energy—or attention—is invested in realistic goals, and when skills match the opportunities for action. (6)

Ordered consciousness is the opposite of psychic entropy / monkey mind. (Csikszentmihalyi doesn’t use the term “monkey mind,” but it seems so much clearer than “psychic entropy,” so I refer to them synonymously.)

I’ve covered a lot of straightforward ground in this series, but they’ve all sort of led up to this larger question of achieving order in consciousness (avoiding a state of distraction). So bear with me as I wrestle with this more abstract topic.

Why accept the monkey mind as a natural state?

Although I like the idea of getting into a flow state, Csikszentmihalyi’s assumption about entropy being our natural mental state seems like a pessimistic view of human consciousness that view reduces the value of our most celebrated quality. Why is humanity’s natural mental state entropy instead of order?

Csikszentmihalyi addresses this question in a short section called “Recovering Harmony” (p.227). Anticipating the objection, he phrases it as follows: “Aren’t people born at peace with themselves—isn’t human nature naturally ordered?” This is also my objection. Why shouldn’t my natural mental state be naturally ordered? If it’s disordered, how did it get that way?

If we can’t have ordered consciousness outside of flow, and we only experience flow during optimal times, what does this imply about the rest of our time? The bulk of our lives are spent outside flow? If flow is difficult to achieve, maybe 1-2 hours a day, it can hardly form the backbone of our mental state. It seems like we should address the root of why we become disordered in the first place, so that we don’t have to revert to infrequent states of flow to escape it.

Csikszentmihalyi on pre-conscious states

Csikszentmihalyi says flow helps us return to a pre-conscious state, almost like that of an animal. Csikszentmihalyi says:

The original condition of human beings, prior to the development of self-reflective consciousness, must have been a state of inner peace disturbed only now and again by tides of hunger, sexuality, pain, and danger. … If we were to interpret the lives of animals with a human eye, we would conclude that they are in flow… (227)

Look over at your cat or dog, and quietly observe their state. Presumably, the animal enjoys peace free from the psychic burdens of self-reflective consciousness. I have a young cat that likes to paw at random objects on the floor as if they were mice. In many ways, the cat gets into a state of flow doing this.

But alas, we humans have the burden of a conscious mind, which leads to psychic entropy (monkey mind). Csikszentmihalyi continues:

The forms of psychic entropy that currently cause us so much anguish—unfulfilled wants, dashed expectations, loneliness, frustration, anxiety, guilt—are all likely to have been recent invaders of the mind. They are by-products of the tremendous increase in complexity of the cerebral cortex and of the symbolic enrichment to culture. They are the dark side of the emergence of consciousness. (227).

Animals don’t experience “unfulfilled ambition” or get overwhelmed by “pressing responsibilities.” They don’t “weigh possibilities unavailable” or “imagine pleasant alternatives.” They aren’t “disturbed by fears of failure” (228). These characteristics represent the “dark side of consciousness,” which came about due to the “tremendous increase in complexity” of our brains and from an advanced culture.

How humans developed consciousness

Csikszentmihalyi doesn’t spend much time on how consciousness is formed (at least not in Flow), and his writing about consciousness is more speculative than evidence-based (due to the nature of the topic), but he briefly touches on it. He says consciousness likely formed due to the following:

- the “biological evolution of the central nervous system”

- “the development of culture—of languages, belief systems, technologies”

- “the dubious blessing of choice”

- the transition from “dispersed hunting tribes to crowded cities … [which] give rise to more specialized roles that often require conflicting thoughts and actions from the same person.”

- the juxtaposition of many different social roles, reinforcing the fact that all “see the world different from one another. There is no one right way to behave, and each role requires different skills.”

- the “cacophony of disparate values, beliefs, choices, and behaviors.”

- exposure to “increasingly contradictory goals, to incompatible opportunities for action” (230)

The overarching theme here is that as civilization grows complex and multifaceted, particularly in ways that prompt reflection, such as by being confronted with contradictory or opposing views or lifestyles, consciousness increases. These more complex scenarios prompt advanced thought.

Overall, Csikszentmihalyi doesn’t seem too concerned with how humans arrived at consciousness (or an advanced state of mind), only that they do experience consciousness, and that the mental state of consciousness drifts toward entropy. However, before dismissing the possibility of a better answer about how consciousness formed, let’s explore one more theory about how consciousness formed.

Note: How humans became conscious is one of the big mysteries of human biology, philosophy, and psychology. “Consciousness” is probably too general and slippery of a term, but I’m hesitant to get into definitions and nuances because this is a deep topic that probably merits more space than I can give it. I want to explore it only briefly.

Origins of consciousness—the bicameral mind hypothesis {#origins-of-consciousness—the-bicameral-mind-hypothesis}

Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow was published in 1990. About 15 years earlier, American psychologist Julian Jaynes published a book called The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. It posits that consciousness was a relatively recent development (just 3,000 years ago), emerging from metaphoric language. The theory is speculative and most experts dismiss it, but they acknowledge a fascination with some aspects of the thesis.

Jaynes says if you look back several thousand years ago, during the time the Iliad was composed (about 8th century BC), you don’t see subjective interiority (consciousness) in the characters. The characters don’t introspect in explicit ways that embody a thinking, conscious mind. There’s no Descartes-style mind at work, no Hamlet soliloquy.

Jaynes says the frequent gods and muses directing events in ancient texts were actually auditory hallucinations from the right hemispheres of people’s brains. The left hemisphere incorrectly interpreted these auditory hallucinations as the voices of the gods. Jaynes called this the bicameral mind (for “two houses”).

As written language evolved, specifically metaphoric language, the bicameral mind started to break down. Those auditory hallucinations, which previously originated from the “gods,” started to be perceived as emerging from the same human mind. As people evolved and the bicameral mind disappeared, the auditory hallucinations from their right brains ceased. Without the gods directing their actions, many people felt abandoned.

Jaynes’ controversial bicameral mind hypothesis caused critics to reconsider their interpretations of gods and muses’ frequent appearances in texts like the Iliad. Many started to think that the gods weren’t literary devices or cultural tropes but rather literal beliefs about what was happening.

Metaphoric language and consciousness

Despite the intriguing hypothesis, there isn’t compelling evidence for it, so it remains a hypothesis. But even putting aside his larger theory, there are aspects to Jaynes’ ideas that are interesting, such as the idea that metaphor gives rise to conscious thought.

Jaynes dissects metaphors into metaphiers (the familiar object) and metaphrands (the unfamiliar), arguing that the “most fascinating property of language is its capacity to make metaphors.” He defines metaphor in the common way: “the use of a term for one thing to describe another because of some kind of similarity between them or between their relations to other things” (48). But even phrases not typically flagged as metaphors are in fact metaphors. For example, if you say, “layoffs are coming,” it assumes that the layoffs are an object, that they have a means of movement (legs?) and that they are heading in your direction (Watch out, the recession is coming to get you!).

Jaynes says “… metaphor is not a mere extra trick of language, as it is so often slighted in the old schoolbooks on composition; it is the very constitutive ground of language.” (48) More importantly, metaphor extends language: “It is by metaphor that language grows” (49). We’re used to “seeing” metaphors as merely literary devices in language, one of many rhetorical techniques available, but Jaynes expands the scope of metaphors to make them the foundation of language and thought itself. Jaynes says:

All of these concrete metaphors increase enormously our powers of perception of the world about us and our understanding of it, and literally create new objections. Indeed, language is an organ of perception, not simply a means of communication. (50)

Metaphoric language helps us consider unfamiliar circumstances and ideas, prompting more advanced thought and ultimately consciousness. Metaphors take us from the familiar into the unfamiliar. By taking us into unfamiliar territory, metaphors prompt us into more advanced thought (and eventually consciousness).

Jaynes continues:

The lexicon of language, then, is a finite set of terms that by metaphor is able to stretch out over an infinite set of circumstances, even to creating new circumstances thereby. (Could consciousness be such a new creation?)” (52)

It’s through language and metaphor that we perceive new circumstances, and awareness of these new circumstances leads us toward more consciousness.

Jaynes also says symbols in language allow us to assemble and manipulate advanced ideas:

Subjective conscious mind is an analog [such as a map] of what is called the real world. It is built up with a vocabulary or lexical field whose terms are all metaphors or analogs of behavior in the physical world. Its reality is of the same order as mathematics. It allows us to shortcut behavioral processes and arrive at more adequate decisions. Like mathematics, it is an operator rather than a thing or repository. And it is intimately bound up with volition and decision.” (55)

If you consider how mathematical operations and computer programming involve converting ideas into symbols that you can manipulate and perform actions against in complex ways, it’s not hard to see how language might perform a similar function. Words act as symbols that we can manipulate in advanced ways, leading to more complex thought.

Externalizing thought through writing

I’m not sure if Jaynes is right about metaphoric language and consciousness (can anyone know?), but there’s widespread consensus that language plays a role in the development of consciousness. As someone who frequently writes, I can attest that written language plays a part in promoting introspection.

When you write something, you’re literally making your internal thoughts external. This externalization allows you to see your thoughts more concretely, almost from another point of view. As E.M. Forster once said, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” Let more time pass (years, even) to the point that you forget that you’re the author of the written text, and the words become even more external and foreign.

The widespread recognition of Forster’s quotation reinforces its validity. The more you write, the more likely you are to know what you think. Knowledge of what you think creates self-awareness, and it leads you to deliberate about whether you agree with what you’re reading or not. All of this complexity likely leads to more advanced thinking. And more advanced thought leads to more consciousness, the ability to step outside our frame of mind and analyze it formally, points of view, to be aware of ourselves and our mental processes, almost like an external observer looking at us.

Regardless of how language works, there’s no greater tool for thinking than writing. Not only can you see your thoughts in concrete form but you can also refine the logic of your arguments, trace out more complex trajectories of ideas, build elaborate narratives, and more.

The first time I became aware of consciousness

Language leads to thought, but thought alone doesn’t trigger consciousness. You need a complex external event to set your thinking wheels spinning in ways that make you aware of yourself.

I remember the specific moment when I first became aware of my thinking mind, or when I recognized my consciousness. When I was about 5 years old, I had a friend who didn’t talk much. One day I had lunch at his house. His mother made us a sandwich and chips, and we sat at his kitchen table, mostly eating in silence. As we ate in silence, I realized that I could think silently in my mind. I could think whatever I wanted, and no one else could know what I was thinking. Did others have this capability? Looking at my friend quietly eating his sandwich, I wondered, was he considering things in his mind too? Or was his mind blank, without any thoughts other than taking another bite of his sandwich?

The juxtaposition of a person in a seemingly opposite state prompts reflection, then awareness. My experience reinforces Csikszentmihalyi’s argument that when we “… see the world different from one another, [recognizing that] [t]here is no one right way to behave, and each role requires different skills,” it moves us toward consciousness.

My wife had a similar experience. She says when she was a young girl growing up in the Mormon church, someone explained to her the doctrine of polygamy, and she felt repulsed by it. She reacted so strongly that she decided that internally, in her mind, she could believe whatever she wanted and wouldn’t have to agree with polygamy. She realized her mind was a private sphere for her alone. No one else could enter her mind castle. It was her house, her space, and she could believe whatever she wanted. It was the first time she realized her private sphere of thought.

The moment I started introspecting while eating a sandwich with my silent childhood friend, or when my wife first realized she could think her own thoughts about polygamy—were these the starting points for a mental state increasingly filled with, as Csikszentmihalyi says, “unfulfilled wants, dashed expectations, loneliness, frustration, anxiety, guilt”? (230) In other words, is this the transition point when we move from the bright side of consciousness to the dark side of consciousness? And if so, is advanced thought itself to blame for our disordered consciousness? Does avoiding introspective thought lead to ordered consciousness?

Paradoxes of consciousness

As humans, we usually celebrate our rational faculties. I love to trace and explore ideas in my head. In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle says the contemplative life leads to the most pleasure: “For contemplation is at once the highest form of activity, since the intellect is the highest thing in us ….” Aristotle says this contemplative state is the highest form of human nature, so maximizing our highest nature leads to the highest form of living.

In fact, Csikszentmihalyi even says philosophy can lead to flow:

… playing with ideas is extremely exhilarating. Not only philosophy but the emergence of new scientific ideas is fueled by the enjoyment one obtains from creating a new way to describe reality. The tools that make the flow of thought possible are common property, and consist of the knowledge recorded in books available in schools and libraries. A person who becomes familiar with the conventions of poetry, or the rules of calculus, can subsequently grow independent of external stimulation. She can generate ordered trains of thought regardless of what is happening in external reality. When a person has learned a symbolic system well enough to use it, she has established a portable, self-contained world within the mind (127)

In other words, the seemingly absent-minded philosopher who is lost in deep thought, running ideas through logical syllogisms to dissect them to their core and then reassemble them back into a whole, enters a flow state, despite heightened consciousness. It seems paradoxical, though they are different types of consciousness. One is focused, directed thought. The other is freeform, scattered thought. Are they really so different?

The entropic mindset Csikszentmihalyi warns against isn’t the philosopher focusing on arguments about abstract ideas, but rather the idle person whose mind isn’t focused on anything at all (monkey mind, not curious mind). It’s “when we are left alone, with no demands on attention, the basic disorder of the mind reveals itself. With nothing to do, it begins to follow random patterns.” (119).

The philosopher’s deep introspection and rigorous examination of ideas, which one might consider the pinnacle of conscious thought, isn’t the same dark consciousness that Csikszentmihalyi says is entropic and unordered. Philosophers get fully immersed and direct their focus on specific subjects, arguments, and other matters of logic and evidence. They immerse themselves so deeply they might appear catatonic, staring off into space while their mind actively explores an idea. Think of this state as the bright side of consciousness, the one that fills you with understanding of the world and human behavior. How then do we go astray with this consciousness and descend into darkness? Is it merely by not having something to focus on? As if by taking your foot off the accelerator in a car, the engine falls apart.

When consciousness trends toward the dark side

Obviously, monkey mind has been around long before tech, but I can’t help but wonder if some technologies have the potential to exacerbate it. Specifically, the internet exposes the human mind to a firehose of complexity and chaos. What is the relationship between surfing the internet, specifically doom-scrolling and boredom browsing, and monkey mind?

In What Technology Wants, Kevin Kelly describes his love for the internet in what is perhaps the most eloquent[ly disturbing] passage I’ve read. He marvels at how the internet compresses randomness into one continuous experience of chaos and beauty:

I am no longer embarrassed to admit that I love the internet. Or maybe it’s the web. Whatever you want to call the place we go to while we are online, I think it is beautiful. People love places and will die to defend a place they love, as our sad history of wars proves. Our first encounters with the internet/web portrayed it as a very widely distributed electronic dynamo—a thing one plugs into—and that it is. But the internet as it has matured is closer to the technological equivalent of a place. An uncharted, almost feral territory where you can genuinely get lost. At times I’ve entered the web just to get lost. In that lovely surrender, the web swallows my certitude and delivers the unknown. Despite the purposeful design of its human creators, the web is a wilderness. Its boundaries are unknown, unknowable, its mysteries uncountable. The bramble of intertwined ideas, links, documents, and images creates an otherness as thick as a jungle. The web smells like life. It knows so much. It has insinuated its tendrils of connection into everything, everywhere. The net is now vastly wider than I am, wider than I can imagine; in this way, while I am in it, it makes me bigger, too. I feel amputated when I am away from it.

I find myself indebted to the net for its provisions. It is a steadfast benefactor, always there. I caress it with my fidgety fingers; it yields to my desires, like a lover. Secret knowledge? Here. Predictions of what is to come? Here. Maps to hidden places? Here. Rarely does it fail to please, and more marvelous, it seems to be getting better every day. I want to remain submerged in its bottomless abundance. To stay. To be wrapped in its dreamy embrace. Surrendering to the web is like going on an aboriginal walkabout. The comforting illogic of dreams reigns. In dream time you jump from one page, one thought, to another. First on the screen you are in a cemetery, looking at an automobile carved out of solid rock; the next moment, there’s a man in front of a blackboard writing the news in chalk, then you are in jail with a crying baby, then a woman in a veil gives a long speech about the virtues of confession, then tall buildings in a city blow their tops off in a thousand pieces in slow motion…. (322-323)

In other words, he loves the web for bringing everything together in one seemingly continuous, paradoxical space.

Since the publication of What Technology Wants (2010), more insights about the harmful effects of internet content algorithms have emerged. Algorithms optimize for what gets clicked the most—usually thought-provoking or sensational content. Thus, the internet firehose isn’t just randomness, but extreme chaos and complexity that challenges your ideas (by presenting alternative perspectives). The firehose of content shocks you into heightened levels of awareness, often forcing you to make sense of opposing lifestyles and viewpoints. It’s content that, as Csikszentmihalyi would say, prompts you to “see the world different from one another. There is no one right way to behave, and each role requires different skills.” On the internet, you see “specialized roles that often require conflicting thoughts and actions from the same person.” You realize that we “see the world different from one another,” that there is “no one right way to behave,” that there are “increasingly contradictory goals” and “incompatible opportunities for action.” In short, the internet offers you a “cacophony of disparate values, beliefs, choices, and behaviors”—streamed right into your brain for many hours a day.

Does the internet become a catalyst for encouraging our minds to jump around in the same way we jump around from site to site, topic to topic, search to search, online?

The internet brings everything together into one experience. It presents the mind with far more chaos and complexity than anything before it. You move from scene to scene as different as night and day, moving across cultural and geographical boundaries without even noticing. You are exposed to ideas of every kind, often contradictory, challenging, or upsetting. Maybe this cacophony pushes our conscious brain into overdrive, such that our mental patterns trend toward entropy rather than order. We get too much awareness, too many associations, too many connections.

Kelly’s depiction of his internet experience is one of “beauty” for technology. He enjoys how so many diverse experiences are juxtaposed into one. But others don’t see it that way. Here is one Amazon reviewer’s description of the internet, riffing off a theme in Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows:

The brain, confronted with a glowing screen and the ability to hypertext its way from one interruption to another across the universe of knowledge from what its buddy in Australia thinks of rutabagas, to the spelling of rutabagas to the history of rutabagas to dishes that can be prepared from rutabagas leaves the brain sliding from one fact of surface interest to another fact even less useful, until it occurs to the brain to pursue the prompt on the pop-up menu and check the weather and get off of this slide onto the weather channel where a five minute video on playful seals on San Francisco Bay can be watched for free which does remind the brain that it could slide over to Facebook and find out if anyone “liked” the picture of the family cat posted an hour ago. And many do. Twenty-three “likes,” praise the Lord. (Cowan)

In other words, the pattern on the internet promotes unstructured thought. You move from topic to topic by seemingly tenuous association, such that after 30 minutes of browsing, it would be nearly impossible to trace back the logic. This pattern fragments any linear, sequential thought into an endlessly random teleportation into different worlds every minute. For a fun video that encapsulates the internet’s randomness, see Bo Burnham’s “Welcome to the Internet” (youtu.be/k1BneeJTDcU).

Internalizing a 19-second pattern

Putting aside the internet’s cacophonous content, the mere pattern of web-surfing behavior might trigger similar web surfing in the mind. A 2014 study found that when people use laptops, “switches occurred as frequently as every 19 seconds, with 75% of all on-screen content being viewed for less than one minute” (Firth 6). Throw in smartphone behavior on top of this, with its attention-fragmenting notifications, and you get continuous context-switching for most of the day.

If we constantly switch online throughout the day (every 19 seconds), is it surprising that our brain might switch topics every 19 seconds as well? When we teach our brain a pattern, it learns to follow it.

What I’ve noticed {#what-i’ve-noticed}

As I read, I noticed a fascinating phenomenon. When I tried to sleep at night, if I had read a book that day (say, 50 pages of something), my mind seemed to follow a more linear, sequential pattern, similar to the calm order in which my eyes moved left to right across a page, following a larger narrative or argument an author was making. The act of reading imbued my mind with more order even in a natural, unfocused state.

One researcher explains that books’ story structure can instill a more sequential order in our brains:

Story structure encourages our brains to think in sequence, expanding our attention spans: Stories have a beginning, middle, and end, and that’s a good thing for your brain. With this structure, our brains are encouraged to think in sequence, linking cause and effect. The more you read, the more your brain is able to adapt to this line of thinking. (“Your Brain on Books: 10 Things That Happen to Our Minds When We Read”)

In other words, your brain gets accustomed to thinking in story structures and imprints that same structure in the brain. This helps internalize sequential and causal thinking patterns.

On days when I haven’t read a book but instead have been immersed online, my brain has a different pattern. Instead of linear, focused thought, my mind skips around more. I get monkey mind, jumping from topic to topic. If I’m trying to fall asleep, my racing thoughts will keep me up unless I put an audiobook in my ear to focus my attention until I fall asleep.

I might not have noticed this contrast in mental states without my smartphone experiment. These past two months, I’ve been more relaxed in my technology rules. Earlier on in my experience, I adopted strict rules about when I would use a phone. My journey away from smartphones led me to read more. When I returned to my smartphone, I relapsed in other ways too, checking sports and news more frequently. Then my work provided me with a phone, equipped with work email and calendar. I started checking work email more often, in addition to checking my own email almost obsessively. I started reading Feedly (an RSS aggregator) more often.

At night I would use Youtube.com for entertainment (as an alternative to Reddit). On Youtube, I even unsubscribed from every channel to see what the algorithms would serve up, hoping the videos would lose their appeal, but they didn’t. I watched multiple videos, usually humor-related, until I was too tired to stay awake.

But when I closed my eyes and tried to get to sleep, thoughts raced in my head. My mind jumped and flittered from topic to topic. The only way to sleep was to stay up (watching more videos or movies) until I was so tired that exhaustion itself put me out.

Unfortunately, the internet itself isn’t something one can obviously abandon in modern life, and as I said before, monkey mind predates the internet (as well as Csikszentmihalyi’s flow). But to avoid the random pattern of unfocused thought (instead of becoming idle and jumping down endless rabbit holes), I started writing interesting quotations from the books I was reading onto a notecard. Then I carried the note card in my pocket. When I had periods of idleness, instead of letting my mind wander and get bored, I would reflect on the quotation and try to ask some questions about it in my mind. The quotation served as a point to ponder, something to keep me from the psychic entropy that Csikszentmihalyi described.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.