2.3 Spatial and scientific reasoning from wayfinding

- Origins of scientific reasoning

- Keeping the wayfinding mindset fresh

- Correlating the map to the world

- Getting lost

Origins of scientific reasoning

Regardless of whether you actually develop successful wayfinding skills, there’s another reason for wayfinding: it stimulates spatial reasoning within your brain’s hippocampus. This gets closer to the reasons why neuroscientists and other academics are fascinated by wayfinding. The hippocampus is the area of the brain that lights up during wayfinding. However, the hippocampus doesn’t just perform spatial mapping, it encodes events in a location context in your memory and gives rise to scientific thinking and imagination.

Some researchers think scientific reasoning developed as a result of early hunters tracking animals by interpreting signs. This is called the social trackways theory. O’Connor says, “Hominids are animals that learned to ‘read’ the tracks of other hominids and animals and eventually infer meaning about events that happened in the past from these symbols. This enabled them to predict future behaviors based on these stories and use them to find one another, avoid predators, and successfully hunt prey” (105). In other words, as early humans tried to find the locations of animals, they had to look closely at tracks and interpret signs in the environment. They had to assemble these signs into a coherent story that would explain which animals had been there and predict where they went.

Louis Liebenberg, Harvard professor of evolutionary biology, says “[trackers] have to create a working hypothesis in which spoor evidence is supplemented with hypothetical assumptions based not only on their knowledge of animal behavior, but also on their creative ability to solve new problems and discover new information.”Liebenberg argues that “rational scientific thinking didn’t originate with the ancient Greeks but with hunter-gatherers” (qtd. in O’Connor, 218-19).

Tracking requires a significant number of logical inferences and deductions. This thinking eventually led to similar analytical thought processes like Sherlock Holmes, Freud, and others, O’Connor explains (101). “Our existence depends on thousands of instances of inference and deduction that allow us to draw conclusions about other people and things, what has happened and what will happen,” O’Connor says (103). The hunter constructs a “narrative sequence” based on perceived signs to indicate what happened in a place and where an animal ventured to (102). These narrative sequences gave way to story and storytelling, which some academics believe is the centerpiece of human intelligence (122-23).

Apparently, this same reasoning process also led to autonoetic thought processes, in which humans are able to see themselves from an outside perspective. The “autonoetic consciousness” is “the capacity to be aware of one’s own existence as an entity in time” (105). If you can imagine why an animal was in a place and where it traveled to, you can apply the same thought processes to yourself. You can observe your own self as if an outside observer, analyzing and perceiving yourself and your actions as if from another person’s perspective.

As you can guess, these reasoning processes aren’t active when people blindly follow turn-by-turn directions in a GPS-based app. If you’re not making decisions, you’re not getting any of the benefits of wayfinding. In fact, most of my wayfinding doesn’t involve anything approaching the kind of observations and deductions required to track animals. In my wayfinding, I study a map beforehand, identify what appears to be a good route, commit it more or less to memory (maybe with some notes on paper, or by printing it out), and then navigate there. I make a minimal number of decisions about the route—optimizing for ease, efficiency, and sometimes scenery.

The type of reasoning involved in animal tracking is much more Sherlock Holmesian. While I was reading this section of O’Connor’s book, one of my daughters lost her iPhone. Other family members looked all day for it without success. Filled with confidence, I hoped I could track down the phone’s whereabouts. Like an early hunter thinking through the details, I narrowed down the last time she had the phone, events that day and since, potential places it could and could not be, a radius from the last known location before the battery died, common places where my daughter interacted in the house, and more. I thought I could think through the problem, or potentially eliminate all other possibilities until arriving at the location the phone must be. Alas, despite my initial confidence, I did not locate the iPhone. It is still lost.

However, the experience made me more aware of this scientific reasoning and how it connects with wayfinding. I think similar modes of scientific thinking could be observed in non-wayfinding scenarios. For example, programmers who track down the source of tech bugs employ similar logical skills. To troubleshoot, programmers might isolate different elements to test. Or, they might strip down a piece of code to its simplest form and then build it back up piece by piece, analyzing the effects of each addition until the code breaks. They might search error messages, log files, recreate the issue and observe different analytics (memory usage, performance waterfalls, etc.) all trying to track down the whereabouts of the faulty code. They might identify all the components in a system and draw arrows in how they interrelate, and do other tests to suss out the issue.

When you’re problem solving, you’re paying close attention to detail and making many decisions and adjustments based on observations and feedback. Although it’s not animal tracking, I’ve spent many hours looking at bike routes in the areas near me, trying to find the most ideal routes. Which streets look safe? If the streets lack protected bike paths, are there sidewalks? Are the sidewalks long unbroken stretches, or are they full of intersections? If it’s just a bike shoulder, how fast are the cars traveling? Can they see me if I’m riding on the road? Does the route get me to a public transportation hub that could connect me to another part of the city? Would a bus, a train, a light rail, or some other transportation service be available at the starting location and destination I want to reach? What combination of car + train + bike would work best to get me there in about an hour? Which segment of the journey is best accomplished by each mode of travel? What’s the maximum length for each segment mode? Would a longer and more scenic route be safer even if it added 20 minutes to the ride? Would an eBike allow me to ride a longer distance or just create other issues? How does rain complicate the route? Is it uphill or downhill? Which time would be best to leave at? If I optimize for time but sacrifice exercise, is that actually saving me time? Can I be productive on a train? What about train productivity during rush hour, when only standing room is available?

I’ve spent days looking at maps, then exploring areas in experiential ways, taking note of the widths of bike paths, the inclines or declines, traffic congestion, stop-and-go momentum with lights, and more. Then I take this feedback and adjust my routes and plans. Does this attempt to find optimal bike routes qualify as wayfinding? Does it involve enough decision-making, experimentation, imagination, logical inferences from signs, feedback loops, and other judgements to cause my hippocampus and prefrontal cortex to come alive? It’s certainly using more of my brain than following GPS turn by turn.

Keeping the wayfinding mindset fresh

With wayfinding, one danger is that once you find a route, that route becomes a habit. When you no longer use your spatial reasoning and deductive powers to wayfind, your hippocampus no longer gets used. The caudate nucleus instead encodes the path as an automated habit. O’Connor says when this happens, “autopilot takes over. You see the white building, it acts as a stimulus and triggers a response to turn left to get to the bakery” (263).

This pattern befalls successful wayfinders, because as soon as you find your way and start taking that route time and again, all the brain benefits of wayfinding seem to disappear. To counter this, O’Connor says you need to vary your routes, try unfamiliar paths, and more. You want to avoid automation taking over. “Take new streets and shortcuts to get places; regularly draw a bird’s-eye view of your environment with landmarks; incorporate new behaviors and routes into your daily life” (268).

Reading this, I thought about how my wife likes to go hiking in the same trail system (Lake Desire). She’s been there so many times (75 or more within the past year, for sure) that she knows the right way to turn on the many unmarked trails. She no longer has to think about whether to turn left or right at the many forks and junctions. Although the trail junctions do have signs, she’s long past the point where she even looks at them. She can put aside any thoughts about wayfinding and focus on a podcast or chat with a friend. She turns at each fork in the trail without even thinking about which way to go. It’s the same way that driving home, when I get to about 2 miles from our house, I no longer have to look at road signs because the landscape is visually familiar.

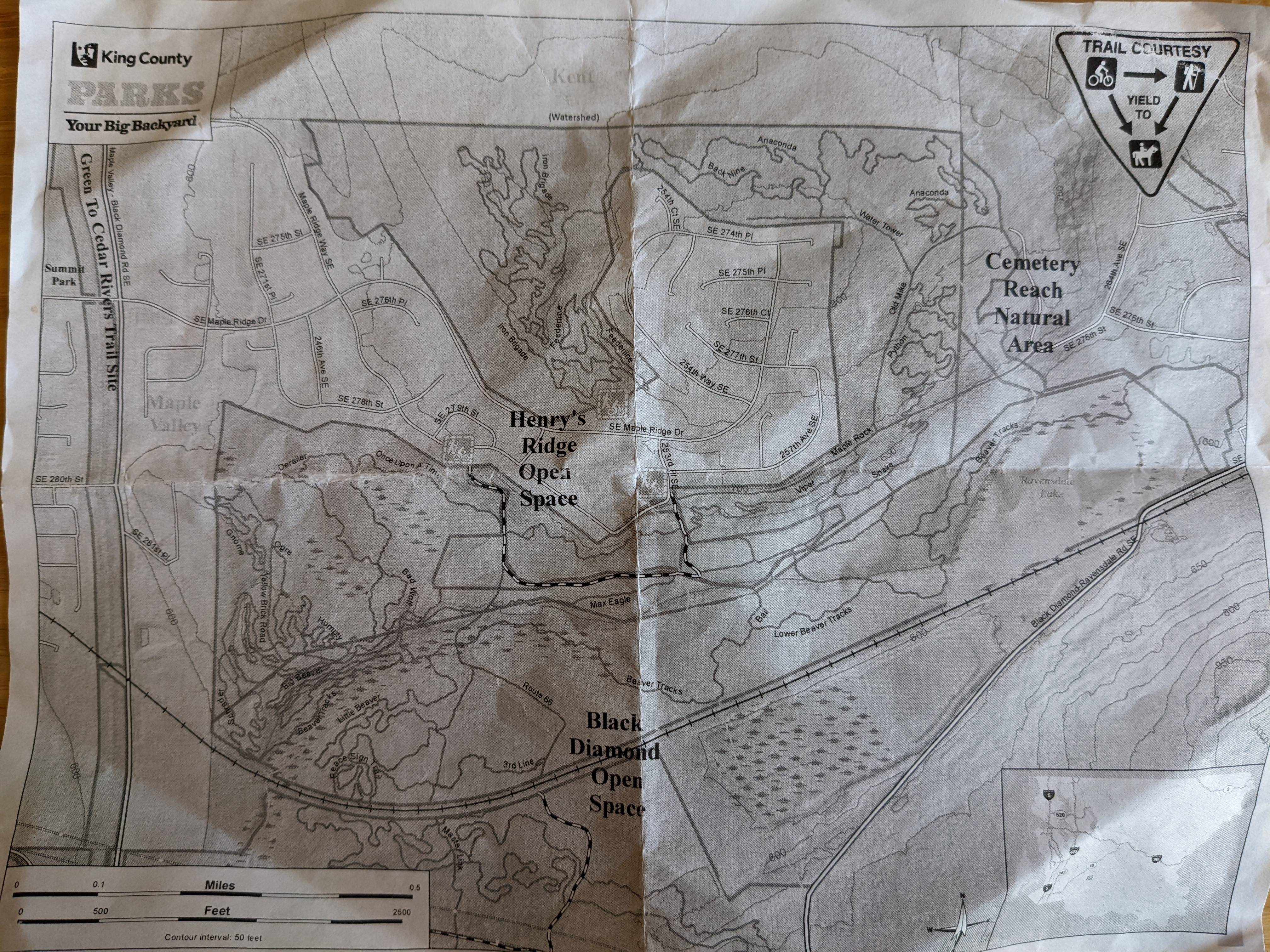

I sometimes accompany my wife on hikes. On the most recent outing, I asked if we could explore somewhere entirely different. So instead of Lake Desire, we headed to Henry’s Ridge. The trails were spaghetti (a compressed pattern designed more for mountain bike riding, it seems, rather than hiking). I printed out a map and we tried to navigate by looking at various signs. However, the map was rudimentary and seemed incomplete compared to the reality of the trails. Nevertheless, we compared signs posted on trees with trail names on the map and made educated guesses.

We walked first along Stingr trail and then on Beaver Trax, over to Ravensdale Lake, then up Snake trail and across Bail trail and then following some wider general access paths and who knows what—eventually, we just started walking in a general direction toward the lake, and then on the return, the general direction toward the car. My wife checked her GPS to ensure we were heading in the right direction.

By trying an unfamiliar route, we were forced into a state of more acute awareness of the environment, especially when we weren’t sure which way to go. This hyper awareness prompted my wife to take more stock of the many types of trees, plants, and other vegetation. At least a half dozen times she paused to use her naturalist app to identify the type of tree/plant/shrub we were passing.

Her awareness and sense of detail were heightened precisely because we’d taken an unfamiliar route in an unfamiliar location. This is my entire point here. When you try new routes and places, your hippocampus wakes up, your spatial senses kick into gear, and your alertness and awareness of everything around you spikes.

Correlating the map to the world

In fact, a few times we could no longer correlate our location on the map. Comparing a map’s drawings with what you see in real life is always a mismatch, which is the whole difficulty of wayfinding. The mismatch reinforces the notion that maps are metaphors for the environment, optimizing for some detail the map maker wanted to emphasize. By definition, maps must be a rudimentary subset of what we actually observe in the environment. This mismatch between the map (what we see on paper) and the world (what we see looking around us) is what forces our brains to make associations, interpretive leaps and to infer conclusions from small details. We interpret a 2D line on paper to represent the trail ahead.

When we’re faced with this mismatch, we’re forced to use spatial reasoning to make some kind of correlation between a model on paper and a model of reality. When the map doesn’t seem to match reality, that’s when the brain’s spatial powers kick into overdrive. On the map, do we see a bending scribble for this trail fork? But why is only one path shown on the map rather than a fork? What other landmarks can we see to confirm that what we’re looking at is in fact this mark on the map?

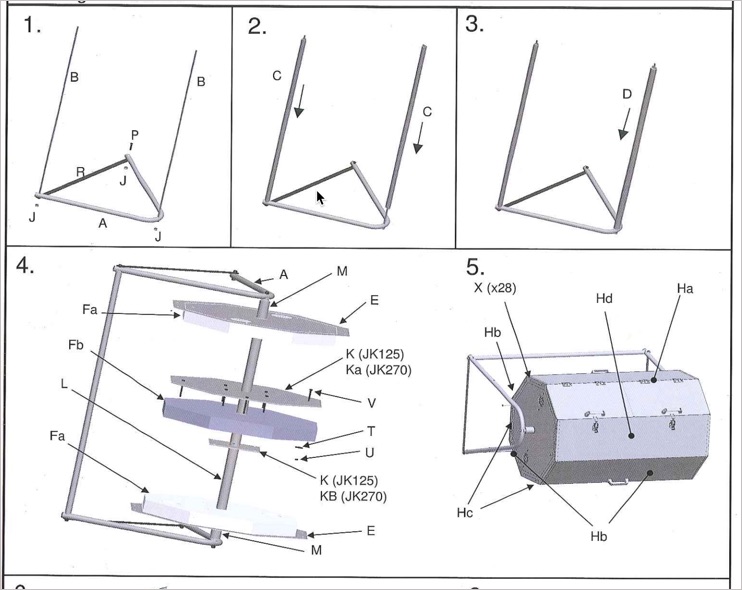

Following a trail map is similar to following product instructions to put together some physical product, such as a dresser or, in our latest purchase, a composter. One locates the instructions, looks at the pictures, and then tries to map the how-to guide’s images to the physical pieces, screws, and other unfamiliar gizmos in the box. Then step by step, we correlate the assembly actions with the various pieces strewn all over the floor until we build the object.

In other words, instructions (especially highly visual ones) are a map that the user must try to follow. It involves a high degree of spatial reasoning, comparing, matching, intuiting, and more. Pieces might look almost similar except for the presence or absence of a single screw hole. Assembling things isn’t something anyone can do without practice. My youngest daughter (11 years old) is a skilled artisan with cardboard, but she flounders when assembling an IKEA desk.

My wife, on the other hand, scored high on the ASVAB test (a military spatial-reasoning test), and seems to have a knack for interpreting instructions to assemble products. When I assist, I often want to be the grunt who does what she says (e.g., insert this screw here, bolt this there) because I know that being the interpreter, her role, requires much more reasoning, spatial interpretation, and identification. It often makes my brain hurt. I supply the screwdriver, she supplies the brain.

Getting lost

There’s also an argument for ditching the map entirely and just going with the flow. In Mary Oliver’s essay “Upstream,” Oliver remembers a time during her youth when others thought she was lost, but she was really just following a river far upstream, entranced by the beauty of the natural world so much that she ceased to take note of her camp location or the standard trails and other boundaries. Remembering this time, she writes poetically:

Sometimes the desire to be lost again, as long ago, comes over me like a vapor. With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats. I didn’t choose them, I don’t fault them, but it took time to reject them. Now in the spring I kneel, I put my face into the packets of violets, the dampness, the freshness, the sense of ever-ness. …. May I stay forever in the stream.” (7)

There’s a kind of beauty in being pulled into a natural setting in an immersive way such that all other matters fade into oblivion. This kind of getting lost means becoming engrossed in nature’s detail rather than in the cares of the world.

Oliver’s celebration of being lost is quite a different type of lost than Bill Kilday describes in Never Lost Again. Kilday, a member of the Keyhole team that created the app that later became Google Maps, recounts a time when trying to navigate through Boston’s streets to find his way home to a wife. His wife, trying to calm a screaming baby, had called him twice asking when he’d be home, but he kept getting turned around and couldn’t find the right exit or turn. Many roads in Boston have the same names (e.g., “Cambridge”) because they were named after the place the road led to. Kilday writes:

My wife, Shelley, at home with a screaming baby, had already called twice. ‘Where are you?’ In frustration, I pounded my fist against my car’s dashboard, yelling at nobody but myself, while driving five miles in the wrong direction down Route 2, looking for the next roundabout. Or maybe it was 3A? From 2000 to 2003, I lived in Boston—and I was frequently turned around. The city was merciless to a transplanted Texan: It was like a foreign language. The locals seemed to take pride in the missing signage, serpentine streets, and roundabouts. You needed to solve a math equation to navigate some intersections.” (xi)

In Wayfinding, O’Connor talks with a landscape historian named John Stilgoe who says that becoming lost is a rare treat, as it allows the mind to wander. Stilgoe says that “busy, rushed Americans … no longer take the time to explore and discover their surroundings and have lost their capacity to even see them directly” (290). O’Connor explains:

To him, getting lost is an opportunity for discovery, one that demands that all the senses come alive, and creates a maximum alertness in which observation and possibility are heightened (290).

When you’re in an unfamiliar surrounding, not sure of which way to go, it changes your sense of perception. Everything looks new.

The other week I went for a walk outside my house and ran across a small path through a wooded area that I’d never noticed before. I took it and soon emerged onto another street that was entirely new to me, as it didn’t have any other connecting streets in our neighborhood. As I walked down the new street, I noticed the houses were much older than the more recent subdivision buildouts. My eyes traced the lines of each house I passed. I felt like I’d stepped back in time to the 1980s, possibly in a different town. The street continued much longer than I anticipated, and I started to second-guess which direction I was heading.

“If I’m lost and I don’t have anyone to ask, I love that feeling,” Joe Stilgo says. O’Connor notes that Stilgo distinguishes “between being desperately lost in dangerous circumstances and getting lost in a generally unknown place. In the latter case, to go off track is really about challenging the borders of one’s familiarity, pressing beyond the known spaces of our understanding and experiences and into the new” (291-292).

I’m sure that if Kilday were to suddenly become intrigued by Boston’s serpentine streets and get lost in thought as he explored the area with novelty and wonder, he would have found his clothes and belongings on the porch when he finally arrived home. Even so, whether you’re intentionally lost or accidentally lost, your perception determines the value of the experience.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.