2.2 Wayfinding requires you to be present in the world

The need to be attentive and present

The foundation of wayfinding involves a mindset of being present with the world around you. You have to pay close attention to the environment you’re interacting with.

O’Connor says, navigation “start[s] with practicing acute observation of the places you already live” (298). As she interacted with various wayfinding cultures—the Inuit, Oceania, Aboriginal Australians—and with wayfinding experts from the neuroscience and psychology fields, she asked people for tips on learning wayfinding and navigation. “Again and again, I was surprised by how simple the answers were,” she says. “Learn to draw,” said one professor, and then continued, “We don’t know how to represent the world well enough. Actually paying attention to the environment, making empirical observations and organizing them into a system—do that” (298).

The first principle of wayfinding is to be attentive to the world around you—so much that you could draw it. You have to be in the world, taking in the full sensory experience, not just the visual landscape, but the topography (inclines, declines), the wind patterns, the light, its history, and basically every detail you can observe and feel.

Being in the world requires that you mediate the world directly rather than by way of a screen. O’Connor says, “…wayfinding is an activity that confronts us with the marvelous fact of being in the world, requiring us to look up and take notice, to cognitively and emotionally interact with our surroundings whether we are in the wilderness or a city, even calling us to renew our species’ love affair with freedom, exploration, and place” (10).

Part of the reason I like interacting with maps so much, as I sit on my computer, is because maps represent a form of what’s out there, in the real world. By looking at places and planning routes, forays to different places, I feel the exhilaration of knowing that, eventually, I’ll no longer be sitting in this computer chair looking at the flat screen of a virtual world but will be physically out in the real world, feeling the sun or rain or looking at gray clouds as I move about on foot, on bike, or use some other mode of travel in the real world.

Unfortunately, even when we go out into the world, modern life erects barriers between us and the world. To get from place to place, we get into our cars and shut the door on the world (putting another screen between ourselves and the world). The sound outside quiets, we adjust the temperature of our artificial environment, turn up the radio, and then move forward without any physical exertion at all. Insulated from the raw experience of the environment, we accelerate across cement landscapes in our own private space, protected from interacting with others except as other car forms. Is it any wonder that, as we cut ourselves off from the experience of the world, our wayfinding skills suffer?

One of the Inuit people O’Connor interviewed said, “Being out on the land lifts you up spiritually, emotionally, and physically. It gives you medication, or meditation, however you want to call it” (36). As someone who spends most of his life working in tech, indoors, looking at screens, I feel a longing for more connection with the outside world.

When I am out in the world, though, it’s often in a car due to the infrastructure we as a society have built. The car as a mode of travel not only insulates us from a more direct experience of the environment, it travels too quickly for us to take in details (225). “In a car when you travel, you miss a lot of country, a lot of stories,” says one of the Aboriginal Australians O’Connor interviewed (193). John MacDonald, an Inuit researcher, says, “The faster you traverse the land, the less observant of it you become” (Connor 78). Speed has an inverse relationship with the details you take in—the faster the speed, the less detail. The less detail, the less interesting. Pretty soon, the outside is just a blur. Passengers often don’t look out the window at all, preferring their phones instead.

The fact that passengers often choose to look at their phones instead of the world passing by isn’t surprising. Many of the roads we take follow the fastest route, so there’s less to look at because the landscape along thoroughfares is generally more lifeless and plain. Driving down an interstate highway is an activity that induces hypnosis.

In this way, modern modes of travel are at odds with developing skills of wayfinding. Wayfinding experts say to be observant of the surrounding landscape, but our modern modes of travel (driving a car, following efficient GPS routes zipping along highways and thoroughfares) strip the landscape of interest and detail. Our minds tune out the surrounding areas and we focus instead on the radio or podcasts as a way to bide the time until we reach our destination. And yet, in many of the cultures O’Connor studied, the journey was part of the reason for the trip. One group in Oceania seemed to embark on a long sailing trip to a distant island to acquire some small grocery item, not for the item, but for the opportunity to sail across the water.

Sailing across ocean blue water is one thing, but driving across town at rush hour is quite another. In The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape, James Kunstler describes the appeal of walking through car-dependent infrastructures in suburban areas as follows:

Here there is no pretense of being in a place for pedestrians. The motorist is in sole possession of the road. No cars are parked along the edge of the road to act as a buffer because they would clutter up a lane that might otherwise be used by moving traffic, and anyway, each business has its own individual parking lagoon. Each lagoon has a curb cut, or two, which behaves in practice like an intersection, with cars entering and leaving at a right angle to the stream of traffic, greatly increasing the possibility of trouble. There are no sidewalks out here along the collector road for many of the same reasons as back in the housing development—too expensive, and who will maintain them?—plus the assumption that nobody in their right mind would ever come here on foot.

Of course, one could scarcely conceive of an environment more hostile to pedestrians. It is a terrible place to be, offering no sensual or spiritual rewards. In fact, the overall ambience is one of assault on the senses. No one who could avoid it would want to be on foot on a typical collector road. Any adult between eighteen and sixty-five walking along one would instantly fall under the suspicion of being less than a good citizen. (116-117)

Kunstler’s book, written in 1993, couldn’t more accurately describe the suburbia where I live (Kent/Renton). It’s not a place where one walks. You drive everywhere. The walk score in my area is 10 (out of 100). If you do have to walk somewhere commercial, it’s usually an unpleasant experience, treading on hot sidewalks beside busy roads with cars flying by at 45mph. When I see other pedestrians here, my first question is usually, why is this person walking here? Are they stranded? Are they homeless?

The other day I decided to bike home from the train station (a 5-mile ride, partly uphill). I rarely biked this segment because there weren’t any suitable bike routes, so I pedaled along the sidewalks next to car-dominant routes. Here are some scenes from the ride:

These scenes wouldn’t inspire anyone. They look like any other suburban city street: unmemorable, boring. At one point I passed a lady sitting on a curb in front of a Starbucks. I couldn’t tell if she was lost or just waiting for someone. She looked down at the cement, as if her life had been one depressing event after another. Or maybe she was just bored and her phone was dead. I couldn’t tell, but her vacant stare toward the ground seemed fitting for the landscape.

In such suburban, car-dependent areas, can one develop an interest in the place? Can you ever develop the emotional attachment necessary to become a close observer of the land in a way that would yield more natural wayfinding abilities? Immersion in the cement infrastructure doesn’t uplift you spiritually, connect you with stories from your past, or invite you to explore its rich detail with a fully present mind. It’s more of a landscape where you want to get from point A to point B in the fastest way possible. It’s no wonder that we’ve lost interest in wayfinding.

In Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, Jeff Speck, an urban planner, argues that a city’s vitality and interest depend on its walkability. Unfortunately, thanks to city engineers and the prioritization of traffic flow, cities have largely been reshaped around the needs of the automobile, with wider streets and faster speeds along those streets. The prioritization of cars in cities “turned our downtowns into places that are easy to get to but not worth arriving at,” Speck says. That pretty much describes the suburban scene we live in. It’s easy to get to many of these places, but are they worth going to? There’s a little shopping district near my house, complete with Fred Meyer, UPS, T-Mobile, and a bunch of other stores that litter the country in similar shopping districts.

For downtowns to be walkable, Speck says “a walk has to satisfy four main conditions: it must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting.” Useful means you can get common household items. Safe means protected from cars hitting you. Comfortable means that many of the streets resemble “outdoor living rooms.” And “Interesting means that sidewalks are lined with unique buildings with friendly faces and that signs of humanity abound.” If walking doesn’t satisfy these conditions, we walk less.

I’ve only experienced a handful of urban hubs that satisfy these conditions. Walking down Broadway in New York, for example, or walking along Capitol Hill’s Broadway Street in Seattle, or walking in the financial district in San Francisco. The unique shops and people on these urban streets give them an interesting feel.

Most downtown areas near where I’ve lived, however, such as downtown Renton or downtown Tacoma, fail to meet any of these qualities. Walking to my local Fred Meyer might be useful, but the walk would take 45 minutes instead of a 5 minute drive. The walk is safe, but the cars are so loud and frequent, you can’t even listen to podcasts. The walk is comfortable in the sense that you’re not on the road, you’re on a sidewalk. But there’s no tree cover or other shade. It’s usually hot, long, and tedious. Finally, as for interesting, walking along these sidewalks does not provide any visual interest at all. There is only the road, cars, and more cement.

Affinity for a place

Paying close attention to the land requires some affinity for the place you’re in. If you have deep cultural, historical, and religious ties to the land, you are more likely to take in those details and remember them. Aboriginal Australians and their Dream Tracks are certainly examples of this. Even a watering hole might have a rich history to it.

O’Connor uses the term topophilia to describe “the sense of attachment and love for place” (296). If you establish a connection to the land, you’ll be more likely to carefully observe its details. “If you’re paying attention and listening, often there is a whole other story, telling us where we are,” explained one of the Oceania people, talking about sailing (245). You can’t see that hidden story unless you slow down and absorb the details of an area.

O’Connor says that to develop topophilia, we have to accumulate treasure maps of memories: “Across cultures, navigation is influenced by particular environmental conditions—snow, sand, water, wind—and topographies—mountain, valley, river, ocean, and desert,” O’Connor says. “But in all of them, it is also a means by which individuals develop a sense of attachment and feeling for places. Navigating becomes a way of knowing, familiarity, and fondness. It is how you can fall in love with a mountain or a forest. Wayfinding is how we accumulate treasure maps of exquisite memories” (297).

Not just maps, but treasure maps. To develop an affinity for a place, you have to learn its history and stories—its treasures. In the United States, we move from place to place every five to seven years, whether for job opportunities or other circumstances (or just boredom). As such, it’s difficult to know an area beyond a superficial level. With such transience, how do we move from superficial maps to treasure maps?

A place doesn’t have to be spectacular to be a treasure map. Our sense of place as home usually has deep roots in our psyche. Think about why one of the first questions we ask each other is “Where are you from?” Why does place matter so much? Where we grew up is much more than just a logistical question. Place references your home. And your home shapes our identity. So how does a place, even as dreary as commonplace drive-everywhere suburbia, become your home?

For O’Connor, her home “was the small, scrappy chicken farm that [she] had loved so much and so briefly as a child” (304), a place that “shaped [her] like clay” (305). I grew up in a small town in a dairy valley (Burlington, Washington), and like O’Connor, I can also still trace the map of my childhood’s neighborhood—the slough in the back along a dirt trail, the roads up to the city’s central park with its baseball fields and dirt mounds for biking, the long gravel roads along the dike out to the Skagit River and its sandy/dirty shoreline, the dirt farm fields where I rode around on my motorcycle, the strawberry fields where, as a sixth grader, I picked strawberries for my first job, the tall cherry tree we used to climb. The places on my treasure map are the small home I grew up in, especially the large tree out front that we used to climb up to watch people pass by. And then the large dirt farm field out back, which runs up to the edge of a dike protecting potential flooding from the Skagit River.

And yet, if a stranger were to drive through Burlington, this area would be indistinguishable. It looks like just any small town whose economic livelihood is waning and where people live in 75-year-old homes that haven’t changed much with the passage of time. But for me, the map is my treasure map.

Although Renton’s downtown area holds little appeal, I am, in fact, located in one of the most beautiful areas in the Northwest. South Seattle might be an unappealing industrial wasteland (with some warehouses and complexes that would make IKEA look small), but southeast King County (Kent, Renton) sits at the edge of the Cascades in a lush, green area filled with tall Fir trees, watersheds, and rolling hills. Drive east for 15 minutes from Kent and, given the rolling rural landscape, you might think you’re in another area entirely.

Taking the scenic route

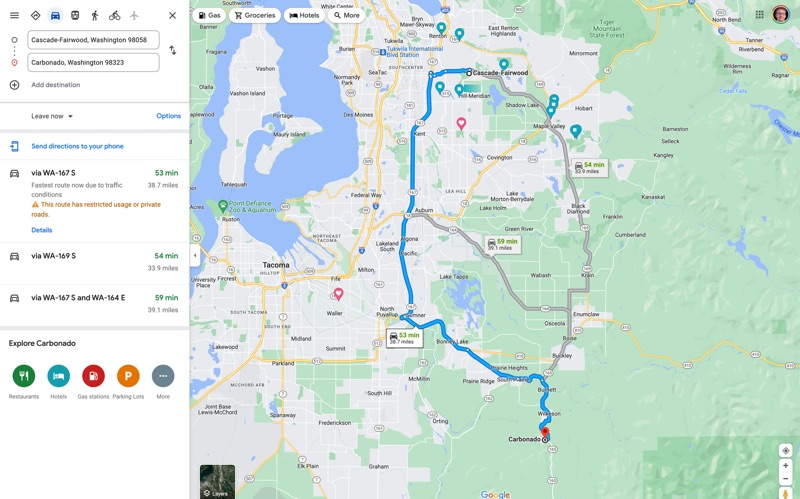

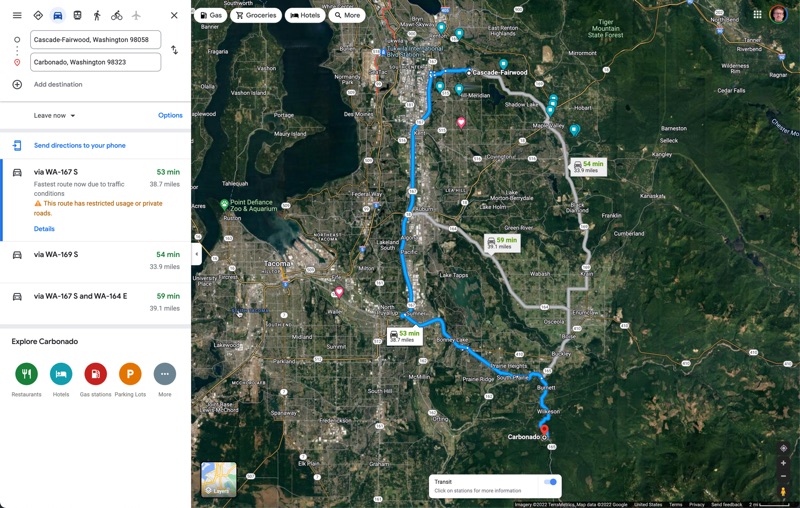

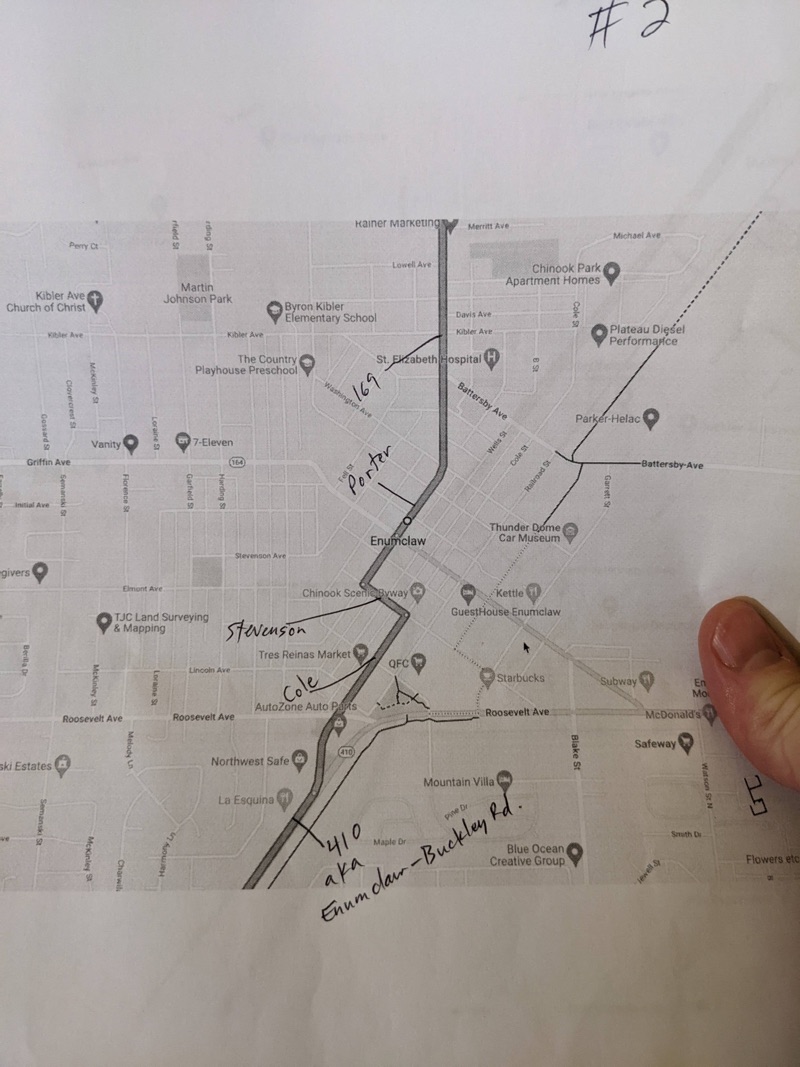

The other week I needed to drop my 11-year-old off at a week-long summer camp near the Cascade foothills. I first routed to the destination using Google Maps on my computer. The initial route followed Highway 167, which parallels I-5. Two alternates were also proposed. Trying to break out of the pre-programmed, lifeless road routes, I decided to travel along a custom scenic route. (Taking the route not optimized for speed is almost never the default.)

The recommended route following I-5 gets you there just 1 minute faster than the scenic route, which passes through the foothills of the Cascades with green wilderness and hills to the east. The scenic route adds just 1 minute of time. The freeway route even adds 5 more miles of distance, which means you’re traveling faster, so everything will be even more of a blur.

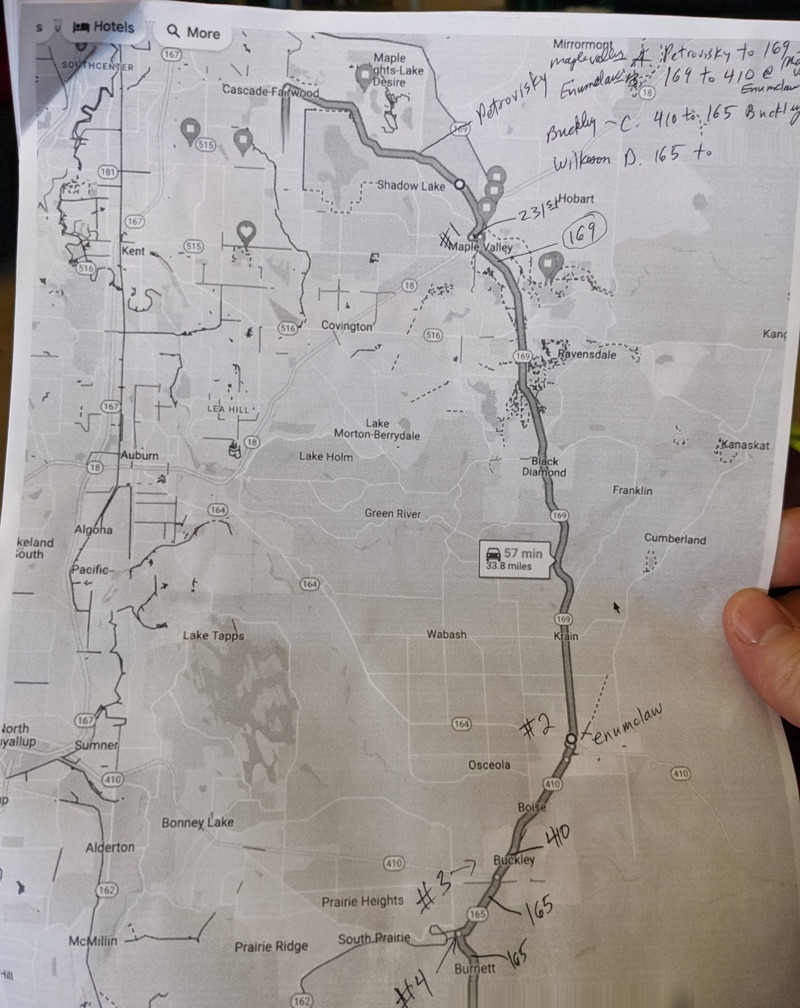

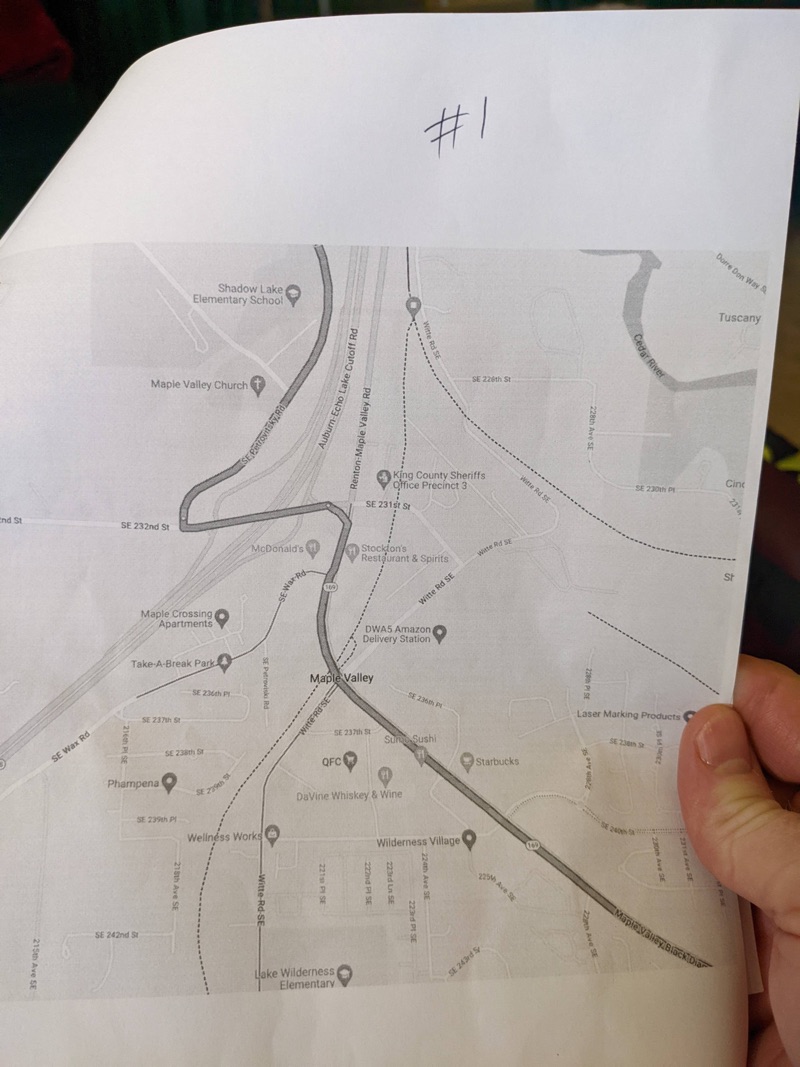

I didn’t want to use GPS to get to the camp, so I ended up printing off the map. Even traveling this short distance (a one-hour trip) made paper maps problematic. My printed map of the area (a GM Johnson City Map) didn’t extend into Enumclaw, and I didn’t have another map of that area with the needed detail. I tried printing off the route overview but it lacked the scale for the various connection points and turns that I’d need to make. This is one problem with relying on a printed map—if you drive more than an hour, you often exceed the scope of the map. If you get a larger scale map, it doesn’t show detailed information in the areas you’re driving. And I didn’t have a Washington Atlas.

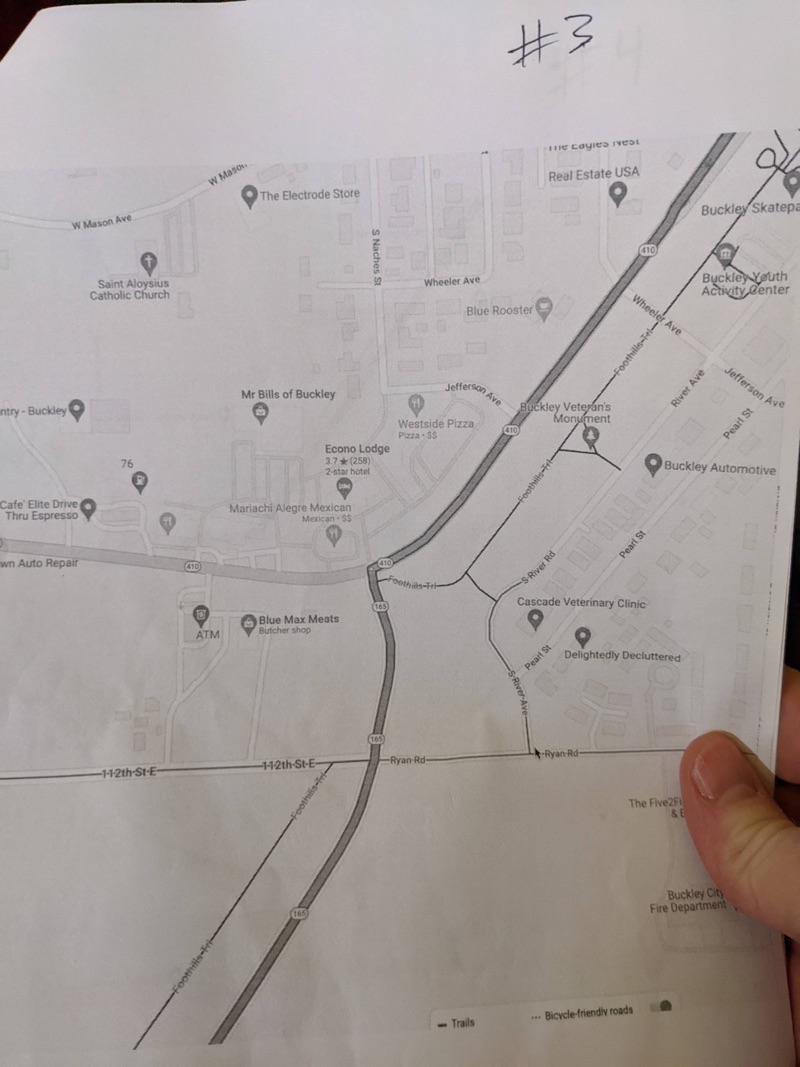

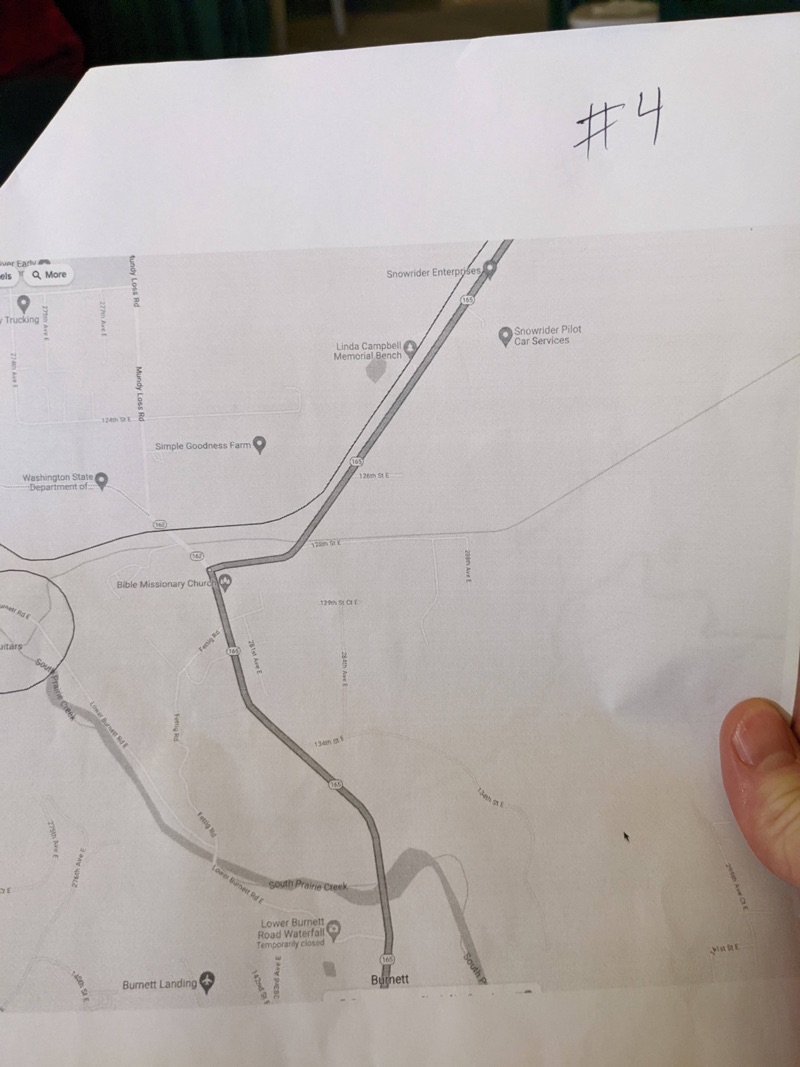

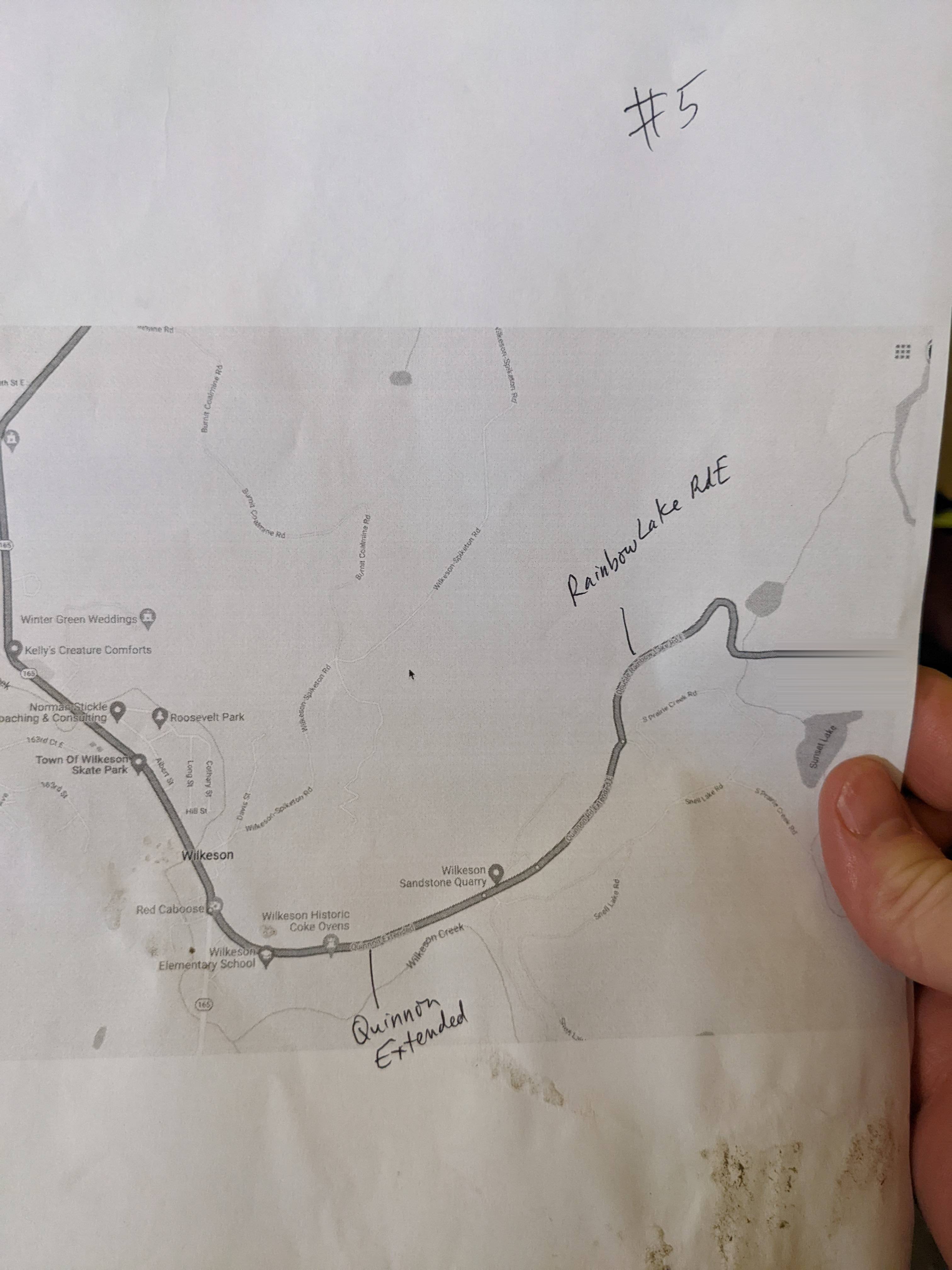

In the end, I took screenshots of the various connection points and referenced them from the larger map, with a few notes.

Albeit tedious, this method also allowed me to study the route a bit more. The drive was, in fact, much more scenic and enjoyable than the time-optimized route along I-5. My 15-year-old and 17-year-old are both learning to drive, so I sat in the front passenger seat, fully attentive and alert (even more so than when I’m driving because they’re both still novices), and navigated for them while they drove. We stopped in Wilkeson and ate at a small diner called a Simple Goodness Soda Shop that had interior decor described as “Americana Mining Town chic.”

Modern GPS technology optimizes our route algorithms on the principle that getting to a destination the fastest way possible is the preferred route. There’s no setting to adjust for that. Instead, you have to venture out of your way to find more scenic routes. Even as my children drove (which can be somewhat terrifying), it was much more peaceful to travel a bit slower and through this lush green area. I developed more of an interest in the towns and scenery. I wanted to know more about the history of places like Buckley, Enumclaw, and Kangley.

If I really wanted to develop wayfinding skills, the next step would be for me to learn the stories of these places, to maybe make day trips into these areas and be more observant of their city details and environment. In short, to cultivate a sense of topophilia. Topophilia doesn’t naturally develop from a picturesque vista or two. Topophilia comes from spending time and having experiences in an area, either by living there or learning from those who do.

<figcaption>Scenery in the green area</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption>Scenery in the green area</figcaption></figure>

At least the paper maps helped me stay focused on the environment. We did get lost briefly, though it involved only a 10 minute detour. I sensed we were off course, checked the GPS to confirm it (I pulled my phone out of my bag), and then backtracked to realign with our planned route. I don’t think GPS itself is bad; it’s relinquishing our own decision-making to the turn-by-turn directions of an algorithm that might be at odds with our goals (like optimizing for speed instead of for place), without thinking about that algorithm or questioning its omniscience.

As we drove, I kept my focus on the area. In other words, I looked up. Some researchers say navigation involves connecting vistas, “traveling along a particular route so as to generate or re-create the temporally structured flow of information that uniquely specifies that path to the destination” (O’Connor, 181). These vistas connect in sequences that mimic the temporal harmony of music. Véronique Bohbot, in The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map,” explains:

Once you have learned the relationship between landmarks, you can derive a novel route to any destination from any starting position in the environment. Spatial memory is allocentric [outside your own perspective], it’s independent of your starting position. You use spatial memory when you can picture the environment in your mind’s eye” (qtd. in O’Connor, 263).

Some landmarks can help orient me—a flowing river, for example, or mountains in the distance, especially Mt. Rainier. Distinctive landmarks aren’t often visible through a barrier of similar-looking fir trees, though. But by studying my route, I’d become familiar with the sequence of towns: Maple Valley to Black Diamond, then to Enumclaw, Buckley, Burnette, Wilkeson, and so on. As we drove, road signs often indicated junctions to those connecting towns (this way, rather than looking for the junction to the 410 or the switch to the 165, you just followed the sign that pointed to the next town in the sequence). Rather than natural landmarks, the small towns themselves provided visual cues about how to navigate without GPS.

Did this more scenic route and heightened attentiveness unlock wayfinding in a way that would allow me to make the journey again by memory? I doubt it. But perhaps if we drove it a couple more times, yes.

Besides wayfinding, though, there’s something else that’s valuable: the mindset that comes from being in control of where you’re going.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.