Tech comm trends: Providing value as a generalist in a sea of specialists (Part IV)

- Identifying where the problems are

- Doc feedback buttons

- Surveys at select milestone events

- Summaries of weekly issues resolved

- Your reactions and input?

Identifying where the problems are

Another gap with specialists involves understanding users — their experience of the product, their feedback, their successes and failures. Generally, engineers are sequestered in their own spaces, isolated from the user experience. By understanding users and then relaying the user experience, you can help provide essential, guiding information to project teams.

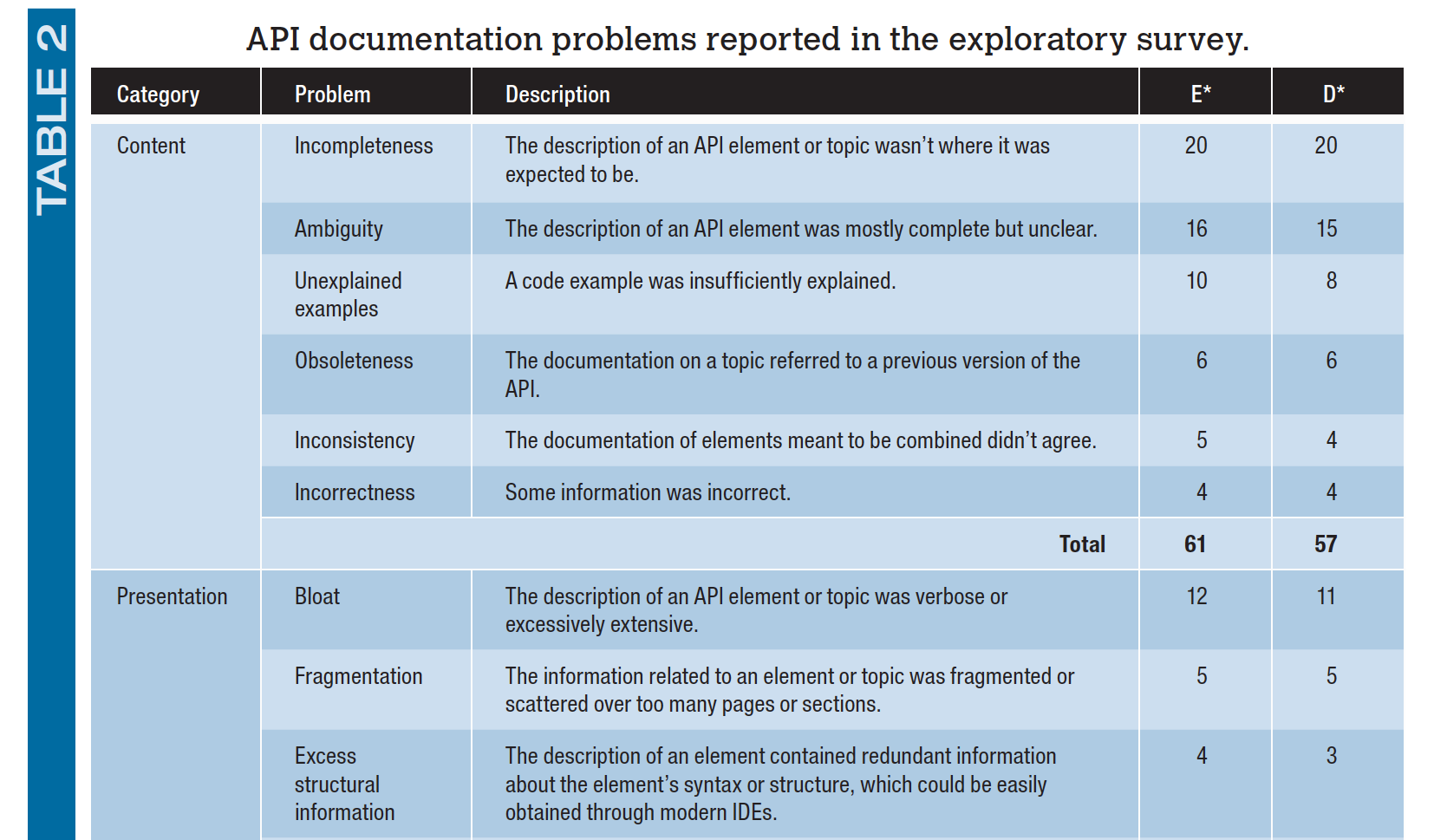

Some academic research indicates that identifying gaps and errors in docs can be one of the main contributions generalists can make. In an article titled How API Documentation Fails (published in IEEE Software), authors Martin Robillard and Gias Uddin surveyed developers to find out why API docs failed for users. They found that most of the shortcomings were related to content, such as information that is incomplete, inaccurate, missing, ambiguous, fragmented content, etc. They summarized their findings in this chart:

The problem, they explain, is that the very people who can fix this content are usually fully engaged in development work. Robillard and Uddin write:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the biggest problems with API documentation were also the ones requiring the most technical expertise to solve. Completing, clarifying, and correcting documentation require deep, authoritative knowledge of the API’s implementation. This makes accomplishing these tasks difficult for non-developers or recent contributors to a project.

So, how can we improve API documentation if the only people who can accomplish this task are too busy to do it or are working on tasks that have been given a higher priority? One potential way forward is to develop recommendation systems that can reduce as much of the administrative overhead of documentation writing as possible, letting experts focus exclusively on the value-producing part of the task. As Barthélémy Dagenais and Martin Robillard discovered, a main challenge for evolving API documentation is identifying where a document needs to be updated.

In other words, simply identifying the gaps in the documentation can provide a huge value for the engineering team. There are potentially hundreds of pages of documentation. How do you know where the problems are, where users are getting stuck, where steps are missing or inaccurate? In short, how do you identify the problems in the content based on the user experience?

The developer authors aren’t going to routinely review the content in meticulous ways. They are mostly blind to any questions or shortcomings users might experience. If tech writers can identify these gaps in the user’s experience of the content (even if they can’t write the content to address the issues themselves), this mere identification can provide tremendous value to engineering teams.

Doc feedback buttons

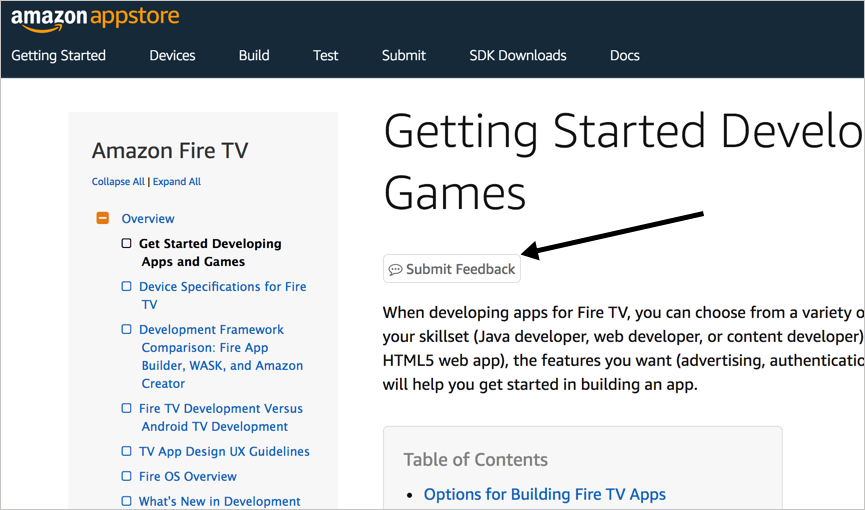

There are a variety of ways to gather this feedback and relay it to the appropriate engineering teams. One of the easiest examples is through the embedded feedback button.

On our docs, we added a “Submit Feedback” button directly below the title, like this:

In other experiments, we had the button off to the sidebar but most people simply missed it. We wanted the button to be unmistakably visible.

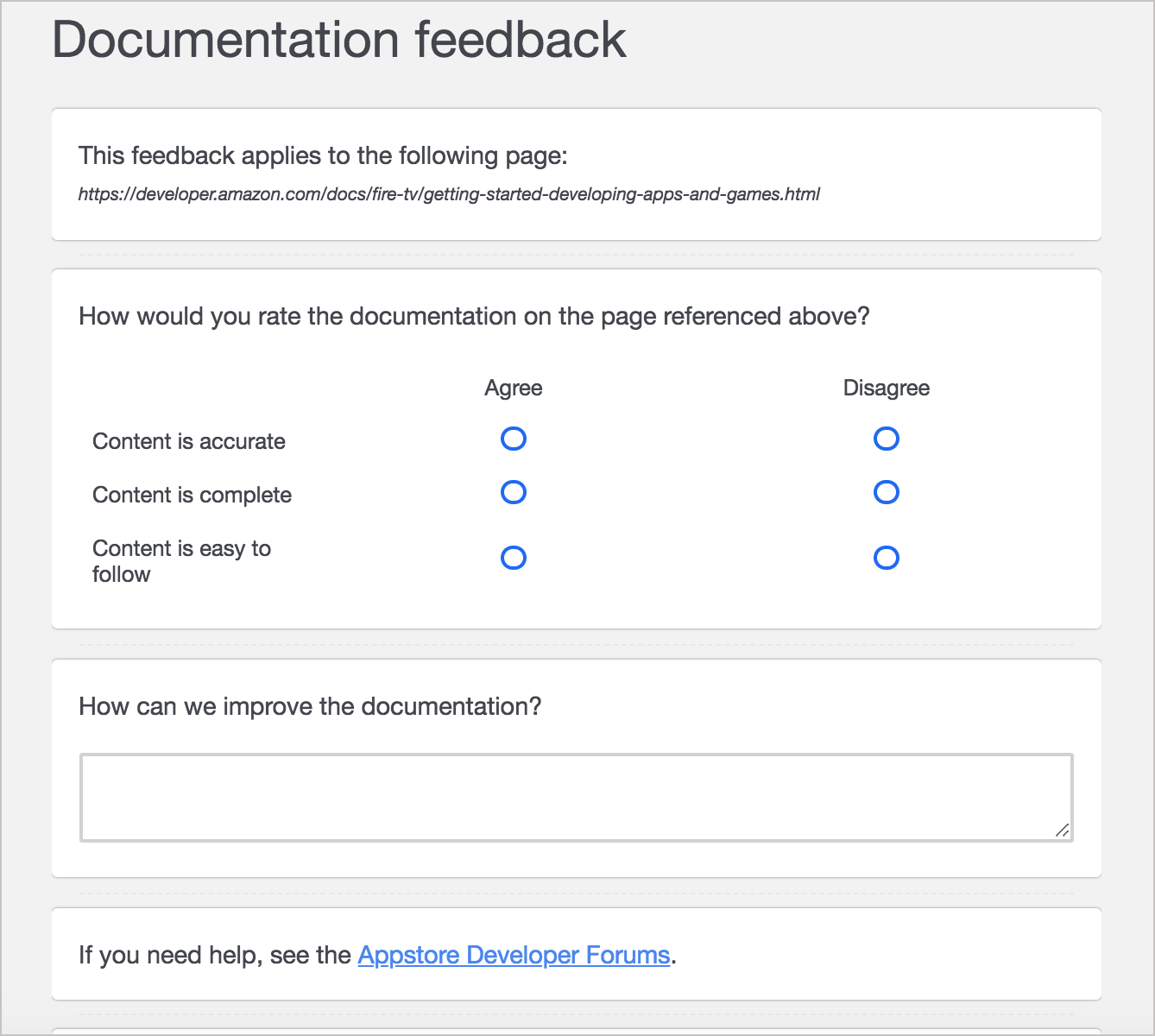

The feedback form is pretty simple. It looks like this:

The form is just a survey. On average, we get only a handful of responses each week, but the responses are usually worthwhile. They identify gaps or other problem areas that we otherwise wouldn’t realize. Since we work with a lot of doc sets, not all of which we directly authored or own, when we receive doc feedback, we create an issue for it in our issue tracker and assign it to the appropriate engineering team to address. In this way, we don’t always play a direct role in authoring the content ourselves, but we do help identify problem areas and connect engineers with those problems.

Surveys at select milestone events

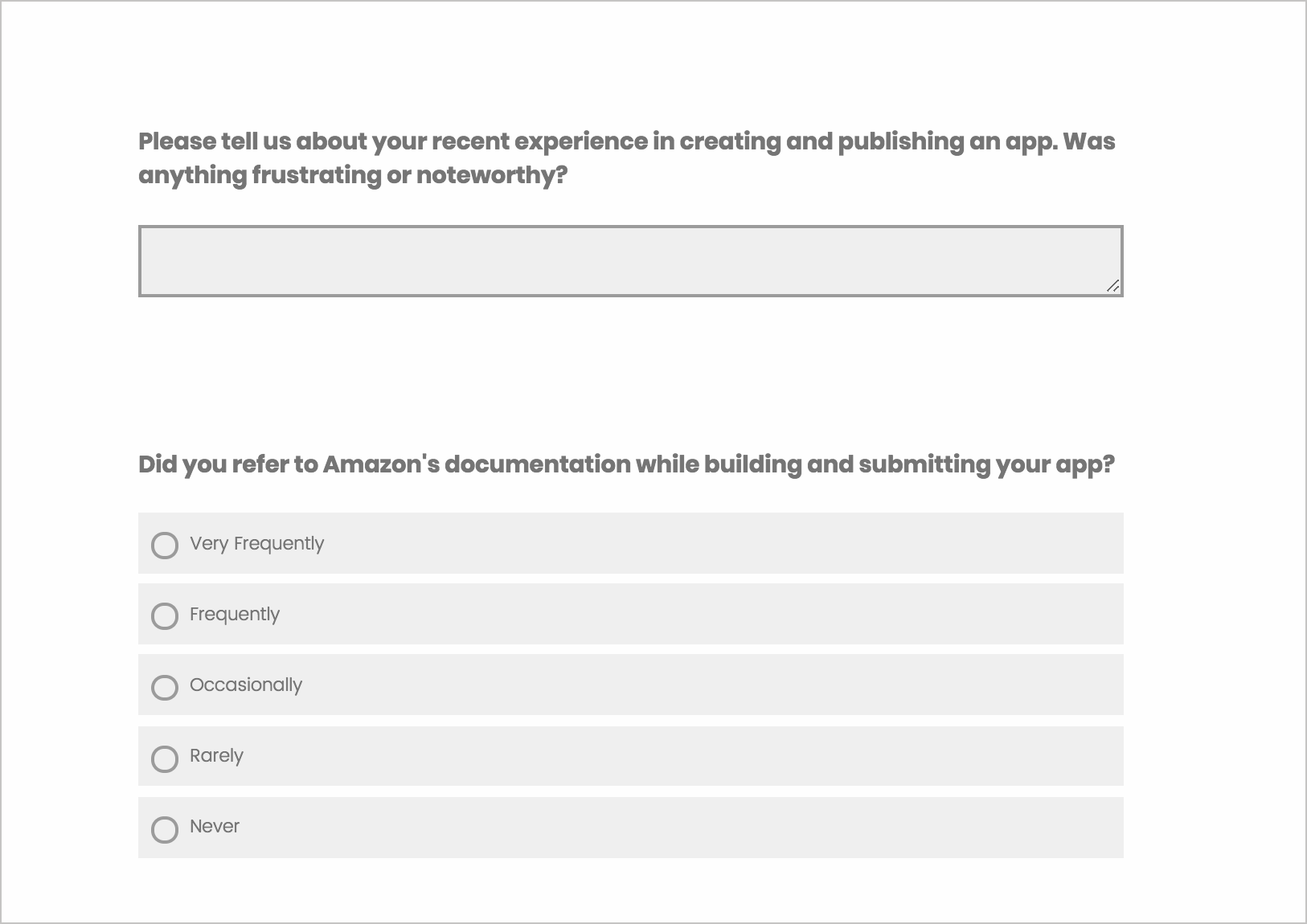

Besides embedding visible feedback forms on doc pages, here are a couple of other strategies. When someone completes a milestone (in our case, when they publish an app in the Appstore), we want to take the opportunity to reach out and ask the developer some brief questions, so we send them a short survey.

I just started doing this, but the results so far are good. I gather up the email addresses for developers with recently published apps and then find out what they found frustrating or noteworthy in their experience.

Responses to the survey usually indicate higher-level trends, noting the experience overall and frustrations with certain processes rather than calling attention to specific errors or gaps in existing documentation pages.

More details on the results of these surveys is still forthcoming. Another group in our organization initiates a larger, more comprehensive survey at least yearly (sometimes more often). The survey comprehensively covers all aspects of the developer experience and highlights larger trends across the user journey.

Summaries of weekly issues resolved

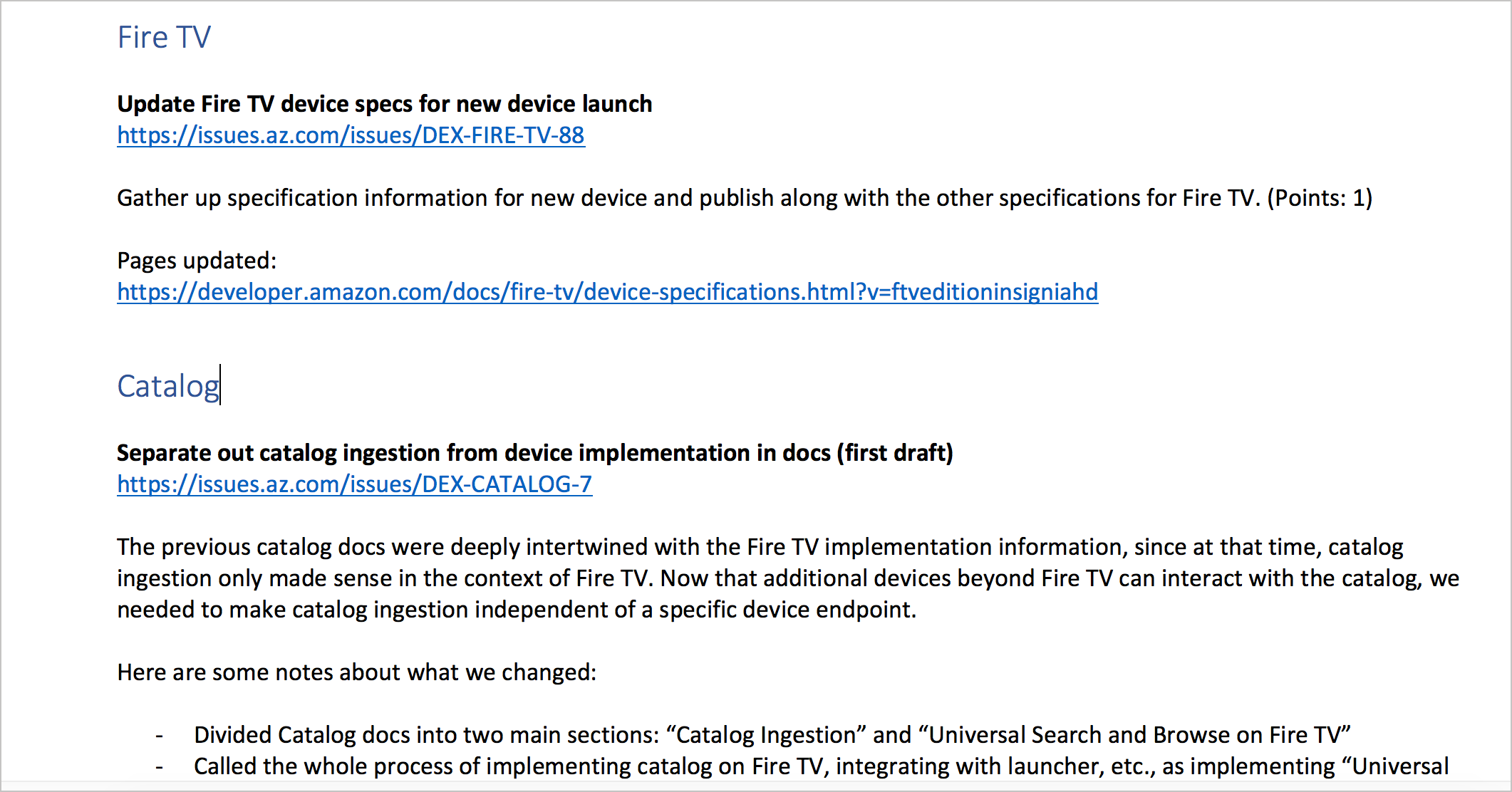

Another technique we use is less common but also has interesting results. Each week, we write a summary of all the issues we tackled during that week. We already do this as a reporting mechanism for our group, but we also send this list of resolved doc issues out to a wider group of people that includes product managers, field engineers, tech evangelists, marketers, and support groups. The email contains all the tickets we resolved and a short description of each issue.

This weekly email works quite well for letting others know what we worked on, since most people tend to be unaware of what doc updates take place (and when and by whom). The regular communication (particularly with the field engineers and support group) lets them know who to reach out to with their doc feedback. Since the field engineers and support teams are our most important groups for receiving doc direction and feedback, we want to keep open the lines of communication and allow information to flow as much as possible.

I’ve found that documentation is a common intersection point for nearly every group in the organization, since almost every group uses docs as tools in their job. Some months ago, I depicted this intersection point in a graphic and posted it on Twitter. This tweet had 73 favorites and 37 retweets:

Marketing uses tech docs in their blog posts, support agents point to it in responses, training uses docs in their materials, product evangelists use docs in their webinars and presentations, field engineers use docs with partners, and even internal engineers all use the documentation.

If docs are at this intersection point within the organization, we should be able to gather feedback from all of these different groups about the docs. Many of these groups regularly interface with customers, which means they can relay the user experience.

Imagine a scenario where, even in a large organization, everyone knows who writes the docs, which docs they work on, and how to influence change in docs. When you have good communication with these groups, feedback flows in.

Much more could be said about how to gather feedback from users. I wrote about this in more depth in Reconstruct the absent user.

Your reactions and input?

You can see the responses (so far) here.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.