Systems thinking: Limits to Growth, Complex Cause and Effect, and Shifting the Burden

- Introduction to systems thinking and Senge’s The Fifth Discipline

- Overview of Senge’s The Fifth Discipline

- Limits to Growth

- Shifting the burden

- Conclusion

- References

- Next post

Introduction to systems thinking and Senge’s The Fifth Discipline

In the previous post in this series, Systems thinking and developer portals, I introduced systems thinking as the discipline that focuses on big picture thinking. I wondered whether tech writers might benefit by focusing on systems thinking, as it seems to be a gap within the infrastructure of tech companies. Tech companies are frequently broken down into highly specialized technology groups that focus only on their stewardship of isolated features, which creates a gap when it comes to seeing the big picture.

After I published that post, one reader, Vinish Garg, pointed me to some related resources and recommended that I check out Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of Learning Organization, which I did. This book turned out to be a great recommendation on the subject and helped me better understand the dynamics of systems.

Overview of Senge’s The Fifth Discipline

Senge’s book The Fifth Discipline (initially published in 1990, revised in 2006) is a classic in the systems thinking genre. The initial chapters on systems thinking (the first 125 pages) deliver the highest relevance to this topic, and the remaining 250 pages focus more on the principles of a “learning organization,” which refers to an organization that embraces a learning mindset.

The learning organization isn’t my focus here, but since the book applies systems thinking to this area, I’ll briefly describe the idea. A learning organization continually asks questions, seeks to learn from different perspectives, explores mental models from different groups, builds on team vision at the grassroots level, and so on.

Senge describes four “disciplines” (pillars) in a learning organization: personal mastery, mental models, building shared vision, and team learning. Systems thinking is the fifth discipline and has key applications in each of these disciplines. The book applies system thinking to each of these disciplines. Senge explains how systems thinking permeates the learning organization disciplines:

“At the heart of a learning organization is a shift of mind — from seeing ourselves as separate from the world to connected to the world, from seeing problems as caused by someone or something “out there” to seeing how our own actions create the problems we experience. A learning organization is a place where people are continually discovering how they create their reality. And how they can change it. (12)

From a systems thinking perspective, each individual influences the company’s outcome rather than being separate and disconnected from it. That product released by another part of the org, which I might have had a tiny part of? I’m not a totally disconnected bystander but am co-creator in the company’s mission and outcomes.

In the chapters on system thinking, Senge describes common patterns and behaviors common to systems in general. These patterns are so common that Senge calls them archetypes. In using the term “archetypes,” think of common story structures that underlie literature. Most stories tend to involve similar structures or patterns — the hero’s journey, man against monster, rags to riches, the quest, the romance, and so on. Most stories can fit into a handful of common patterns. In the same way, systems share common patterns and plots that you can observe time and again. Becoming aware of the archetypes governing system behavior helps you better see the forces that drive change and influence within systems.

Senge provides a more straightforward description of each archetype in Appendix 2, so see that for a more comprehensive treatment. I’ll summarize those archetypes (patterns) that stood out to me, relating them to documentation and elaborating in my own way.

Limits to Growth

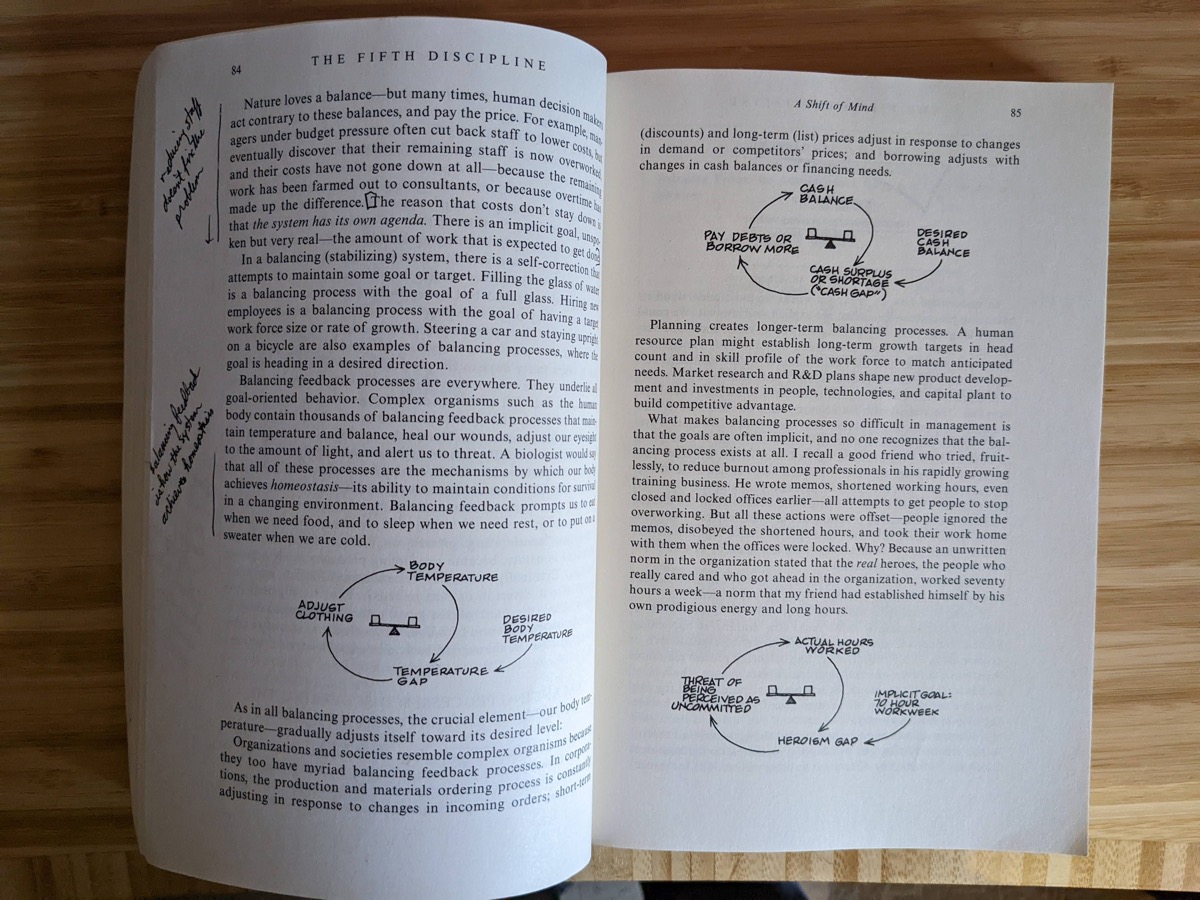

The Limits to Growth archetype shows that growth often slows from initial success to a flatline and later decline because the system compensates or counters with a balancing force. Senge compares the situation to a carpet bubble — you try to push that bubble out of a carpet, but as you flatten the carpet, you just end up pushing the bubble elsewhere (57).

The system compensates for certain gains by countering with other forces, almost like the system is a living organism, actively strategizing countermoves to resist change. Senge defines the Limits to Growth archetype as follows:

A reinforcing (amplifying) process is set in motion to produce a desired result. It creates a spiral of success but also creates inadvertent secondary effects (manifested in a balancing process) which eventually slow down the success. (94)

As an example, Senge says, “We might ‘solve’ sudden deadline pressures by working longer hours; eventually, however, the added stress and fatigue slow down our work speed and quality, compensating for the longer hours” (95).

In another example, Senge describes managers who cut staff to reduce expenses only to find they must now pay contractors more because the same amount of work is expected to get done, or the company must spend more on overtime pay. “The system has its own agenda,” Senge says. “There is an implicit goal, unspoken but very real — the amount of work that is expected to get done” (84). If the system can’t get the work done through staff that are no longer there, it finds another way: by overworking the staff that remain.

In the recent post in my smartphone series, From smartphones to Netflix: moving past plateaus in growth, I explained how I initially had great success in getting rid of my smartphone. I read a lot more, seemed to have better focus and concentration, and was feeling less stressed. But then gradually, I started watching Netflix more. I’d shifted the distraction time from my smartphone to the TV. That’s because I hadn’t really fixed the underlying problem of distraction, so after some gains in one area, the system found a way to push back with a balancing force elsewhere. The carpet bubble simply moved.

As another example, think of dieting. Many years ago, I decided to go vegan (for a week). I avoided cupcakes and dairy only to realize that I was gorging on chips and nuts instead, and ended up gaining more weight. Reason being, the body (a system) has an agenda: to gather a certain amount of energy. When cupcakes weren’t available, the system countered with another option to achieve stasis.

To identify the Limits to Growth archetype, Senge says to ask, “What ‘slowing action’ or resisting force starts to come into play to keep the condition from continually improving?” (102) Most importantly, the answer isn’t to double down on the action that gave you initial success, nor even to play whack-a-mole with the carpet bubble moving around the org, but rather to identify what’s really causing the carpet bubble in the first place.

Limits to Growth applied to documentation

How might the Limits to Growth archetype apply to the documentation world? Consider a scenario where you’re writing and publishing massive amounts of documentation, like a publishing win streak. You’re getting copious amounts of information from engineers, complete with details and code snippets and even error message codes. You’re publishing document after document onto the developer portal, looking like a rock star. You’re 10x more productive than your colleagues.

But then bug reports start coming in related to all the new documents. To find the needed information, you have to track down people no longer in the same roles as before. The fixes require tedious testing and verification. Without the pressure of a pending release, reviewers avoid getting back to you; they reschedule meetings and blow off the follow-up action items.

The system has found a way to limit your growth. There’s a counterbalance that has emerged to bring your initial success to a flatline, and then to a decline. Pretty soon, you haven’t published a new document for months, and during your annual review, as you gather up your accomplishments, you have seemingly nothing substantial to show.

Complex cause and effect

Complex cause and effect isn’t an archetype so much as a pattern related to limits of growth. It naturally follows that when you begin looking for the causes explaining limits to growth (for example, why are we suddenly declining?), you naturally turn to cause and effect (what’s the cause for our slowed growth?).

Systems thinkers look at cause and effect in more complex ways. Cause and effect aren’t often tightly coupled, and the effect might come many months after the cause. There might be interim events that confuse the true cause behind the effect. The organizational distance between cause and effect might also be broader than what most people immediately see, with fixes in one organization creating problems in another part of the organization (58). These different groups might never interact, yet the cause-and-effect relationship could exist between their groups.

Senge explains:

Underlying all of the above problems is a fundamental characteristic of complex human systems: cause and effect are not close in time and space…. There is a fundamental mismatch between the nature of reality in complex systems and our predominant ways of thinking about the reality. The first step in correcting that mismatch is to let go of the notion that cause and effect are close in time and space. (63)

In other words, systems thinkers look beyond the obvious factors and expand their notions of time and space when analyzing cause and effect.

How does the complex cause and effect pattern relate to documentation? Using developer portals as an example, a change in tools one year might not show an effect until several years later, when team productivity might unexplainably slow down. The initial docs-as-code system that simplified authoring through a streamlined Markdown format, which everyone seemed to learn overnight and welcome with open arms, might now be leading to repeated Git merge errors as writers, unaccustomed to content management through Git, accidentally push unreleased branches into production.

Or perhaps a new topic added to the developer portal by one group (releasing a new version of Android) might create issues with the instructions written by a different group (the group developing the ACME API, whose instructions don’t match the new Android version). The two groups are likely in different parts of the company. The company releasing the new version of Android sees only fixes to problems, happy to put that old clunky version in the rearview mirror, while another group in the org inherits problems related to the fix. Now in the new group, many tools no longer work and the instructions must accommodate multiple versions, some unsupported.

It can be hard to see the causal relationships when groups are siloed from each other. As such, we tend to latch onto more visible near-term events as causes. Senge says seeing short-term events as the causes “may be true, but they distract us from seeing the longer-term patterns of change that lie behind the events and from understanding the causes of those patterns” (21). In other words, just because a CEO announced a new org structure last month, it doesn’t mean the high turnover this month is a direct cause of the reorg. The turnover could be a consequence of some other factor, such as gradually declining salary levels due to rising inflation.

Seeing cause and effect across siloes

The specialized silos in an organization make it especially difficult to trace causes and effects, since the influences usually spill across department boundaries. Senge says companies break themselves into smaller components, and these siloes make it harder to see cause and effect relationships.

Senge explains:

Traditionally, organizations attempt to surmount the difficulty of copying with the breadth of impact from decisions by breaking themselves up into components. They institute functional hierarchies that are easier for people to “get their hands around.” But functional divisions grow into fiefdoms, and what was once a convenient division of labor mutates into the “stovepipes” that all but cut off contact between functions. The result: analysis of the most important problems in a company, the complex issues that cross functional lines, becomes a perilous or nonexistent exercise. (24)

For example, even if “Alpha” group and “Omega” group work on the same product, if the company componetizes them into distinct groups within the organization, with different reporting chains, all-hands meetings, goals, and other unique fiefdoms, pretty soon they look only within their group rather than at the larger system, even though they’re obviously both contributing to the product outcome.

Senge never talks about the Butterfly Effect, where the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in one hemisphere might be responsible for hurricanes developing in another, but a systems thinking mindset would consider it. Cause and effect relationships aren’t straightforward, and they aren’t one-way. “In systems thinking it is an axiom that every influence is both cause and effect. Nothing is ever influenced in just one direction,” Senge says (75). These principles lead to the idea of mutualism, which suggests that members of a system influence each other bidirectionally.

“Reality is made up of circles but we see straight lines,” Senge says. “Herein lie the beginnings of our limitation as systems thinkers” (73).

Reality is much more intertwined, with circles showing points of interaction and feedback loops.

Cause and effect with documentation

Let’s bring the complex cause and effect pattern to the tools example with documentation. The mutualism (reciprocal influence) echoes the “Actor Network Theory” that surfaced in my conversation with Guiseppe Getto during his work with wikis and iFixit. Bruno Latour looked at all the actors within a network and even included tools as actors because those tools had reciprocal influences on the users. The tools used influenced the type of content created, which is particularly true in wiki systems where communities engage in collaborative content creation processes that involve feedback loops within feedback loops. As Guiseppe says, “We pick up a tool and use it without fully considering how that tool is influencing us.” I also argued this line in How you write determines what you write, and others have echoed the same with Marshall McLuhan’s argument that “the medium is the message.”

At any rate, no matter what the actors are, Senge says, “The key to seeing reality systematically is seeing circles of influence rather than straight lines” (75). Straight lines are much easier to comprehend. They map better with our brain’s limited comprehension of the world. But if you read Senge’s book, you’ll see that it’s full of circular diagrams, or figure eights, where the relationships between different components within a system are depicted.

Shifting the burden

Another archetype Senge describes in the book is Shifting the Burden. This archetype fits great with the Limits to Growth and the complex cause and effect pattern because it’s basically misinterpreting the problem. Instead of addressing the fundamental cause, people interpret a set of symptoms as the problem instead. This shift not only fails to address the fundamental cause but through neglect, exacerbates it.

Senge defines the Shifting the Burden archetype as follows:

An underlying problem generates symptoms that demand attention. But the underlying problem is difficult for people to address, either because it is obscure or costly to confront. So people “Shift the burden” of their problem to other solutions — well-intentioned, easy fixes which seem extremely efficient. Unfortunately, the easier “solutions” only ameliorate the symptoms; they leave the underlying problem unaltered. The underlying problem grows worse, unnoticed because the symptoms apparently clear up, and the system loses whatever abilities it had to solve the underlying problem. (103)

One of the best examples, Senge says, is addiction. With alcoholic addiction, Senge says people start drinking in response to some stress (for example, increased workload, marital problems, or maybe the loss of a job). The symptomatic solution manifests itself as negative emotions (feeling depressed, anxious, hopeless, afraid, etc.). These negative emotions are symptoms of the fundamental cause, not the fundamental cause itself. (Just like sniffles and sneezes are symptoms of a cold, but the fundamental cause is really the viral infection.)

But rather than addressing the fundamental cause (such as formulating strategies to decrease the workload, increasing communication with your spouse, or building your skillset to find employment), the person shifts the burden to focus on the symptomatic solutions instead. Alcohol does wonders for addressing those feelings of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, fear, etc. The buzz melts those negative emotions away and gives the person confidence and good feelings. The drinking makes them feel better for a while, relieving the stress/tension and giving the appearance of having solved the problem.

All the while, that original problem keeps building and becoming worse. The workload or marital problems grow more severe. The employment outlook grows less and less likely. As a result, the negative emotions return, but even stronger. So they drink some more to address those symptoms.

In the case of addiction, a physical addiction soon sets in and makes it even worse because now you have two forces to contend with: the insurmountable problems (workload, marriage, employment) and the physical addiction. Senge explains:

What makes the shifting the burden structure insidious is the subtle reinforcing cycle it fosters, increasing dependence on the symptomatic solution. Alcoholics eventually find themselves physically addicted. Their health deteriorates. As their self-confidence and judgment atrophy, they are less and less able to solve their original workload problem. … stress builds, which leads to more alcohol, which relieves stress, which leads to less perceived need to adjust workload, which leads to more workload, which leads to more stress. These are the general dynamics of addiction. In fact, almost all forms of addiction have shifting the burden structures underlying them. All involve opting for symptomatic solutions, the gradual atrophy of the ability to focus on fundamental solutions, and the increasing reliance on symptomatic solutions…. The longer the deterioration goes unnoticed, or the longer people wait to confront the fundamental causes, the more difficult it can be to reverse the situation. (108-109)

In a weakened state (constant drunkenness), the person can only see one solution to alleviate the tension: more alcohol.

Documentation and shifting the burden

This dynamic explains addiction, but how might it relate to documentation systems? How do we shift the burden with documentation? Consider this scenario. A product is released but receives little adoption. The product team feels that the API isn’t intuitive enough, and the documentation is confusing as well. So the product team doubles down on developer UX resources to make the parameters intuitive, simplify the response structures, and add more endpoints. The product team asks the tech writers to make the docs better, so the tech writers add conceptual diagrams, split the content into shorter, more digestible pages, add more examples, format content into bulleted lists, and add glossaries.

With these fixes, the product team hopes to have addressed the issue, but partner adoption still lags. Meanwhile, team resources attrition, there’s less time because the roadmap has moved on, and no one is left to refactor the API. What’s really going on, however, has nothing to do with the technical ease of the API and documentation comprehension. The partner is actively choosing not to adopt the API because the data it returns actually has little value to their business case. It’s a low priority for them. In designing the API, the product team failed to align the company’s goals with the developer’s goals, and this API serves the former rather than the latter.

I wrote about this misalignment of goals in my Simplifying Complexity series, Principle 8: Align the product story with the user story. In that post, I talk about an experience at Amazon working on Fire TV apps that would simplify the building of Android apps for TV content. The team assumed that the barrier blocking partner adoption was the technical challenge of building apps. If we could just make it easy to build an app, we would unlock a flood of new content, we thought. But in reality, the challenge wasn’t so much the technical challenge of the app but in producing worthwhile content. Those who had worthwhile content wanted to monetize it. In lowering the technical bar, we ended up attracting low-quality content that almost seemed the equivalent of spam. Had we investigated more deeply what factors were blocking high-value content creators from developing apps, we might have taken a different approach instead of building a simpler tool.

Conclusion

There are many highly valuable sections in Senge’s book that I haven’t covered here. As I explained in the previous post, developer portals present interesting intersections of content. The content in a developer portal is usually generated from different groups in an organization, most of them siloed from each other. By adopting more of a systems thinking approach, we can move past more shallow, linear thinking and sees larger interactions involving limits to growth, cause and effect, shifting the burden, and more. Systems thinking requires a lot of effort and deep thinking, but when you start seeing patterns and archetypes that Senge mentions, the dynamics come more sharply into focus.

References

Johnson, Tom. How you write influences what you write — interpreting trends through movements from PDF to web, DITA, wikis, CCMSs, and docs-as-code. idratherbewriting.com. Feb 20, 2020

Johnson, Tom. Principle 8: Align the product story with the user story. idratherbewriting.com. July 31, 2018.

Johnson, Tom. Reciprocal knowledge networks and the iFixit Technical Writing Project – Conversation with Guiseppe Getto . idratherbewriting.com. July 25, 2018.

Senge, Peter M. The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Broadway Business, 2006.

Image credit: Images were generated through Midjourney, an art AI tool.

Next post

Continue to the next post in this series: ‘Putting together things’: Articulating a thesis about the effects of hyper-specialization on documentation.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.