Thoughts on Transforming Documentation Processes presentation at WTD: Evaluating the trend to treat documentation as code

Listen here:

You can watch the Transforming Your Documentation Process presentation here:

The panelists were Leon Barnard (@leonbarnard), Zach Corleissen (@zachorsarah), Ted Hudek (@tedhudek), and John Bulava (@jbulava).

(It’s funny that WTD lists the Twitter handle for each participant – in reality they should list the slack handle of the person on the WTD Slack channel.)

Riona started the panel by posing the problem that started her documentation transformation journey at Google. In internal tech surveys at Google, employees noted that documentation was hard to find. When you did find it, it was often incomplete or inaccurate. As a result, you didn’t know if you could trust the documentation (it might be outdated).

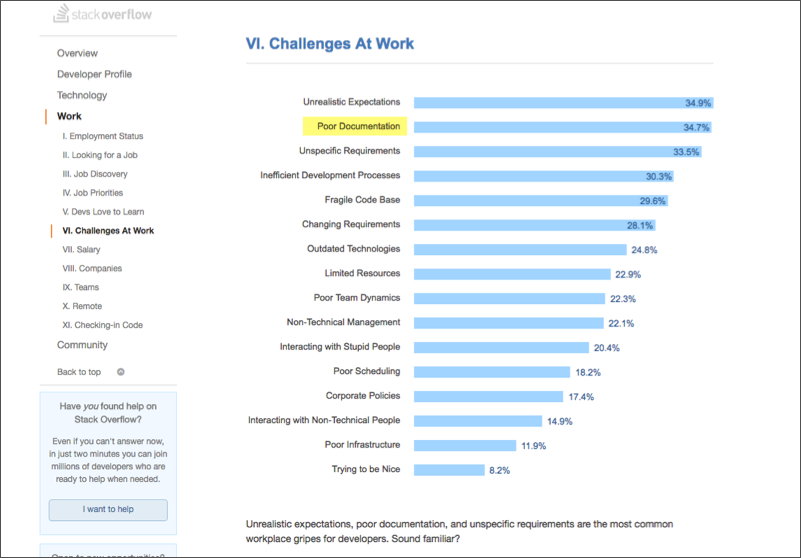

Riona said the survey’s findings closely paralleled those from the 2016 Developer Survey on Stack Overflow, which found that poor documentation was one of the greatest challenges in the workplace:

50,000 developers took the survey on Stack Overflow. Even if the sample is biased toward people who are inclined to value good documentation (and hence provide informaton / survey responses on Stack Overflow), it’s hard to dismiss the results about the importance of documentation to developers.

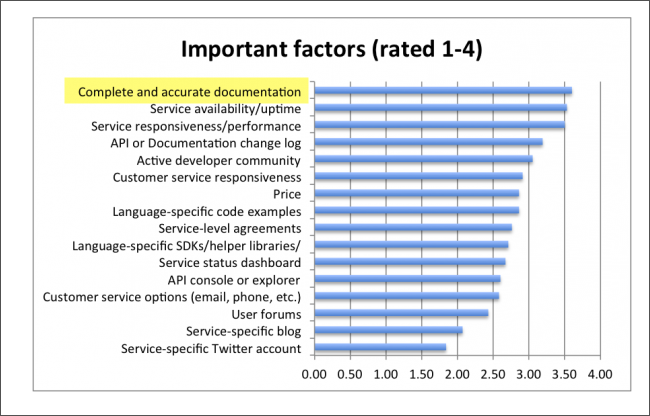

As more support for the value of docs, a 2013 survey conducted by Programmableweb (which included about 250 developers) also found that “complete and accurate documentation” was the most important factor in an API:

(As exciting as it is to find these surveys, don’t get too excited – few people seem to take them seriously, as evidenced by the steady decline or flatlining of employed tech writers. But let’s not dwell on that.)

The four panelists Riona chose all moved their documentation process toward openness and collaboration in similar ways:

- Leon implemented Hugo, a static site generator, along with Swiftype for search. In their new model, customer support agents contribute content directly using text editors and commits.

- Zach at Rackspace implemented a number of open source tools (which process Markdown) to leverage contributions and involvement with developers. The writers at Rackspace process hundreds of pull requests each month from contributing developers.

- Ted at Microsoft moved toward another open model involving Markdown with a repository. Anyone can contribute docs, and contributing developers have a lively, quick process that seems to have a tremendous momentum.

- John at Twitter is moving away from their Drupal environment and looking into Sphinx and other similar processes (though he’s still in the conceptual stage). Twitter apparently gave a seminal talk at last year’s WTD conference that influenced a great many attendees to embrace docs as code.

Referring to these transformation trends, Riona said there is “change in the air” – you can feel it in the breeze and on the water. Without question, many writers are moving towards a model that treats doc as code, closing the gap between engineering and tech comm, primarily integrating documentation into Github repositories and other code workflows with engineers.

The idea is to put docs in a space developers will look at and feel comfortable interacting in. This enables developers to easily make doc updates themselves and fosters more collaboration and community by having an open contribution process. These visionary writers want to move away from the model where only a few technical writers are allowed editorial access into the inner documentation sanctum.

But will treating docs as code achieve these technical writers’ goals? With Riona’s model, she says she’s having success. She looks at code commits and analyzes the number of times developers update the readme file when pushing updates. She finds that developers are updating the readme about a third of the time. This is because the docs are literally embedded in the code repositories, exactly where engineers prefer to work.

I wrote more about Riona’s doc process and previous WTD presentation here. If you haven’t listened to her talk, definitely do so. It’s inspiring.

Riona works in internal documentation for engineers. Will these other writers, who are more focused on external docs, be as successful in their efforts? Is the “docs as code” trend just another documentation fad, something to come and go, like wikis, or DITA? (ha ha)

More importantly, will treating docs as code actually solve any of the problems about documentation being poor, incomplete, and hard to find?

Although I’m a passionate Jekyll user and advocate treating docs as code, I’m wary about over-hyping this trend, as I don’t think it will actually solve the problems in a significant way.

Case in point, look at wikis. 10 years ago, wikis were all the rage. Wikis were (and still are) the epitome of openness and collaboration. They invite anyone to write, publish, and share information. But for some reason, wikis didn’t stick. About their only success is in replacing Sharepoint for internal information platforms at companies. (For more detail about why wikis failed, see When wikis succeed and fail.)

If wikis didn’t take off, why do we think this more current transformation process – writing docs in code repositories using text editors and following Markdown syntax – is going to be any more successful? Maybe Riona’s use case is too specific to internal engineering documentation only?

And if wikis didn’t inspire everyone at the company to contribute, what will inspire them? Why didn’t the wiki model prove to be a successful catalyst for enabling openness, information sharing, and doc contributions?

I don’t mean to completely undervalue success of wikis. Nearly every company has a wiki, and even though no one can ever find anything on it, people continue to add information to it. But very few wikis are used as external documentation platforms. Splunk and Genesys are some exceptions I know of (they use Ponydocs, a fork of Mediawiki).

99% of engineers have absolutely no interest in dedicating the lengthy amount of time needed to write, edit, and maintain documentation on a regular basis. This is precisely why technical writers exist. If engineers loved to write docs, we would not have jobs.

Even if engineers do want to write, they don’t have time for it. Look back at the Stack Overflow survey – the number one challenge is “unrealistic expectations.” Companies expect engineers to work little miracles each day, turning out new APIs and software applications overnight rather than over a period of months or years. (See my post, Why “Programming Sucks” and the fallacy of documentation in the context of code chaos for more details about why programmers have little time to spend writing documentation.)

I do think the move toward docs as code is positive, if only because the open source model is compelling and preferable to vendor lock-in, proprietary platforms, expensive tooling, black boxes, marketing, and other characteristics of the old guard model. (That’s another post, though.)

The reason the whole tech comm community hasn’t jumped onto the docs-as-code bandwagon is because it has yet to decidedly prove itself. It’s still novel – interesting and fun to use software engineering tools and workflows with docs, but the payoff? It helps tech writers get closer to engineering, for sure, and that proximity of environments is helpful.

At the end of the day, though, good documentation – the kind engineers would find helpful, credible, and productivity-enabling – is hard to write. It takes time and a lot of research to pull together code samples and good comments, sample apps, visual diagrams, tutorials, clearly articulated and logical concepts, easy-to-follow tasks, Hello World tutorials, and more.

Once published, maintaining docs requires regular updates, constant vigilance, and more. You need to keep aware of forum threads, support cases, newly added tickets, code changes, and more. All of this takes time and perseverance.

Good documenation is not easy to write – too often we look for a magic bullet with tools to solve our problems. Tools won’t solve the problem of poor documentation. At times tools alleviate some of the burdens of the authoring process, but at the end of the day, it’s the content you create that determines whether your documentation is helpful or not. Tools do not create content. People do.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.