Some advice if you're just starting out your technical writing career

- Just starting out your career

- Avoid becoming Jerry

- When years of experience is detrimental

- Confronting anxiety about getting older

- Five ways to stay young (even as life wears on you)

- Avoid becoming Jayden

- Five ways to level up past novice mode

- Conclusion

Just starting out your career

If you’re just starting your career as a tech writer, this post is for you. You could be a student just graduating college, or someone who is transitioning from another career. There are many options and challenges at this point in your path.

To kick off this topic, let’s start with a question. You’ve just been assigned a new project, and you have to pick another tech writer to work on it with you. You have two choices:

Would you rather work with someone with 25 years of experience, or someone with 2 years of experience? Does it matter? Why or why not?

At these two extremes of the work experience spectrum, there are some common generalizations you’re no doubt familiar with. For workers with 25 years of experience, they might be too set in their ways, resistant to change, wed to specific tools, and often cynical and negative to the leadership around them.

Opposite to these workers are those with just a couple of years of experience. These workers might be mostly reactive, waiting for someone to assign them tickets, indicate the contact points, spell out doc needs, and define other details for the work. This person might require a lot of handholding and management.

Of course, these profiles are extremes. And I’m exaggerating the behaviors to make a point about what characteristics to avoid. If either generalization seems offensive, note that my larger goal is to explain how to avoid these extremes. Many people avoid them by implementing the principles I’ll talk about in this post.

To make this discussion more engaging, I’ve given these two profiles names: Jerry (left) and Jayden (right).

Avoid becoming Jerry

Meet Jerry. He has 25 years of experience and has worked at a variety of big companies.

At this point in his career, Jerry has become overwhelmingly negative. What happened during Jerry’s 25 years to make him bitter? Fictitious deadlines (for which he busted his butt getting docs ready), inexplicable layoffs (some of which he escaped, but not all), failed projects from poorly researched user needs (which required enormous documentation work only to be canceled at the last minute), CEOs oblivious to engineering best practices (and who never champion docs but rather bounce the tech comm team from group to group), and more.

In Jerry’s view, his manager and other senior leaders are incompetent. Product teams frequently loop him in at the last minute, providing little respect for the work he does. They assume he’s a tech newbie, even though he has extensive code experience. Jerry hasn’t devoted time to learning anything new in tech comm for years because everything he reads online seems so superficial. No matter the conversational scenario, even if you start out bearing good news, Jerry manages to turn it into a negative. Worst of all, he has constant backaches from sitting all day.

When years of experience is detrimental

I start off by describing Jerry to make a point: years of experience isn’t always an asset. Many times younger employees are much more desirable, not just because of presumed technical familiarity but due to other characteristics.

In The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization, Peter Senge (talking with other managers at a business conference) describes what young leaders possess:

…many of the more experienced managers at the conference began to see how their past knowledge and accomplishments could actually be an impediment in learning change…. By contrast, the young leaders were able to remain open, and, through their genuine inquiry, often enabled shared understanding and commitment in ways that strong advocacy can impede…. The young people work at remaining unattached to their views. (p. 371)

Young leaders are often open to change, are unattached to their views, have genuine inquiry, and share a commitment with others. By contrast, leaders with many years of experience might be more closed off to change (I’ve seen this before and it never works). Their previous experiences might have persuaded them about certain views (not this again …), and they might have little interest in deviating from what they found to work in previous roles (what’s the point of doing it this way? I already know what works).

As you progress through your career, how will you avoid the same trajectory as Jerry? It’s easy to retain the attributes Senge describes when you’re just starting out and haven’t had to deal with all the nonsense that Jerry has been dealing with for years. The trick is to retain your youthful attributes despite everything that’s going to happen during your career.

Confronting anxiety about getting older

Many tech workers have anxiety about getting older, and for good reason. In San Francisco, there’s even a camp people can attend to deal with becoming “old.” In New Luxury Retreat Caters to Elderly Workers in Tech (Ages 30 and Up), the author explains:

In and around San Francisco, the conventional wisdom is that tech jobs require a limber, associative mind and an appetite for risk — both of which lessen with age…. Their anxieties are well founded. In Silicon Valley, the hiring rate seems to slow for workers once they hit 34 ….

The social narrative is basically, midlife is a crisis and after a crisis you have decrepitude,” Mr. Conley said. “But you actually are much happier in your 60s and 70s, so why aren’t we preparing for that?”

Youth have the advantage of naturally possessing a more limber mind, making new connections, and taking risks, according to the article. I wrote about the fear of aging in a post titled Confronting the fear of growing older when you’re surrounded by young programmers.

In my post, I conducted a survey asking whether others felt any anxiety about increasing in years, and what they’re doing to stay young. 73% agreed or strongly agreed with the following statement: “I sometimes fear what will happen as I get older in the technology field.”

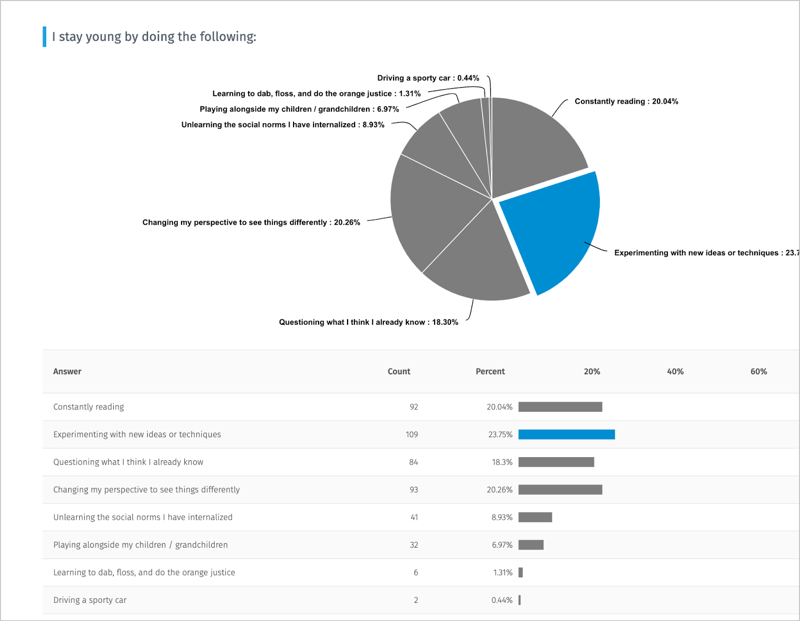

When asked what people do to stay young, the top results (from 140 respondents) were as follows:

- Experiment with new ideas or techniques (109)

- Change my perspective to see things differently (93)

- Constantly read (92)

- Question what I think I already know (84)

This was just an informal, fun survey to get a general pulse on the topic. (You can see the full survey results here.)

Five ways to stay young (even as life wears on you)

Based on the trends in the survey and my own experiences, I recommend these five ways to stay young (and avoid becoming Jerry):

- Read

- Experiment

- Ask questions

- See mental models

- Take risks

I’ll expand on each of these principles in the sections that follow.

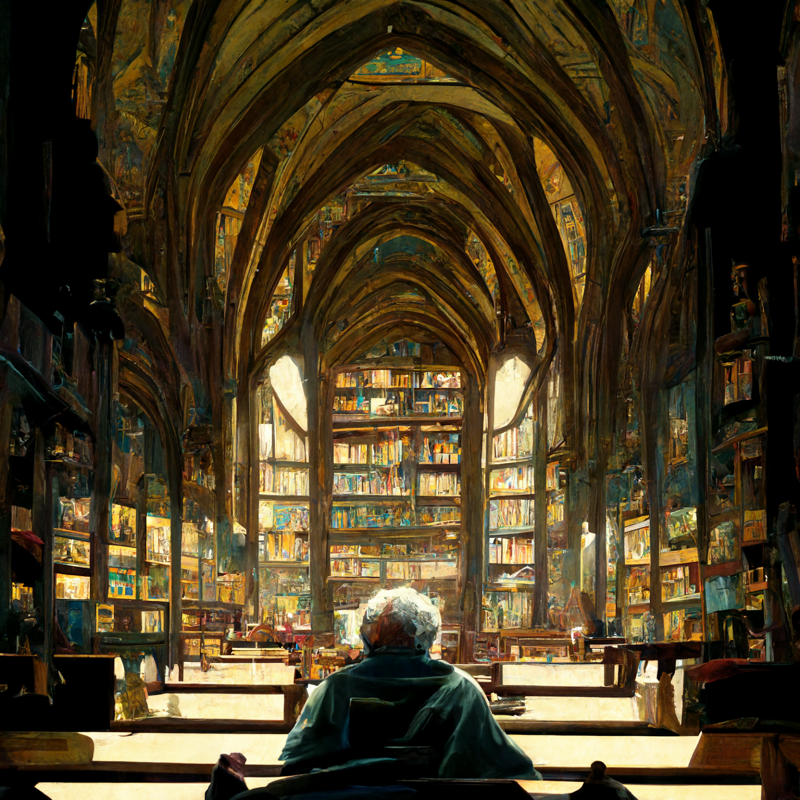

1. Read

Reading introduces you to new information, which helps you continue learning. Continuing to learn helps you keep an open mind and stay receptive to new information that might contradict or supplement existing information you have.

In reading, focus on high-value content, such as books, journal articles, or other in-depth content. Scrolling Twitter and other social media feeds involves reading, but the information is often low-value. Consider printing content out and annotating it with a pen as you read.

Without any incoming information through reading, we continue operating on our existing knowledge and experiences. As such, we’ll be more likely to remain fixed and repeat our same approach again and again.

2. Experiment

Experimenting with new techniques, tactics, tools, and processes can be a way to expose you to new ideas as well. The experiments might change previous assumptions or lead you to new epiphanies or other insights.

When I did my smartphone experiment and gave up my smartphone for a time, it led to many new ideas and feelings. Another experiment, moving from WordPress to Jekyll, and then adopting docs-as-code tools for documentation, likewise led to many new realizations and ideas.

In this post, I’m experimenting with a new tool for creating images: Midjourney. Using this art AI tool led me to question some techno-skeptic ideas that I’d recently been following, and I started to believe that maybe anything is possible with tech. Perhaps I just wasn’t patient enough.

Experimentation should naturally follow from reading. If you’re learning new ideas from the content you’re consuming, try the ideas out.

3. Ask questions

Asking questions is also key to retaining a young, open mindset. When you ask a question, you move in the direction of the unknown to the known, and it can sometimes be exciting to uncover new ways of looking at the world.

When we start asking questions, we often come to realize how little we know. The most mundane, taken-for-granted topic can turn upside down with the right question. It’s only when we start asking questions that we recognize our lack of knowledge. The most basic, almost fact-like idea can seem perplexing with the right question (like when a child regularly stumps you with a “why” question).

Asking questions about whether there are “non-trends,” or trends that have fizzled, led me to an entire series of posts called Trends to follow or forget.

In asking questions, be sure to turn the questions onto yourself as well, interrogating your own assumptions and beliefs. Turning questions onto your own point of view can help you avoid defensiveness and myopia.

Questions also help you build personal skills. Have you ever talked to someone who never asks you questions of any kind during the course of a conversation? These one-sided “conversations” are my least favorite.

For more posts on asking questions, see the following:

4. See mental models

Mental models are the stories people tell themselves to make sense of the world. Peter Senge says mental models constitute one of the four disciplines in a learning organization. He defines mental models as follows:

Two people with different mental models can observe the same event and describe it differently, because they’ve looked at different details and made different interpretations.” (164)

I had a recent family experience that reinforced the importance of mental models. One of my daughters had been complaining about another girl at school who was turning others against her. Though she was once a friend, this girl had since become more of an enemy. To my surprise, the girl’s mother reached out to us one day to complain that our daughter and others were bullying her daughter. What? I wanted to say it was the opposite.

But my wife asked to see the Discord threads that were at the heart of the friction between the two. As my wife looked through the exchanges, there was some evidence that my daughter had acted inappropriately. Looking at the data started to change our views. It also helped my daughter see her actions from another perspective as well, making her open to the idea that she had acted inappropriately too. She could see how the other girl felt that she was sort of being bullied. (I didn’t totally agree, but I could understand that the story might not be so straightforward as I previously thought.)

This is the beauty of thinking about mental models: it frees you from the idea that events have only one interpretation. When you can see multiple interpretations for the same data, it helps you keep a more open mind about the interpretations.

To get a better sense of mental models, Senge recommends these strategies:

Ask ‘What is the ‘data’ on which this generalization is based?” Then ask yourself, “Am I willing to consider that this generalization may be inaccurate or misleading?’ (180)

Actively inquire into others’ views that differ from your own (i.e., ‘What are your views?’ ‘How did you arrive at your view?’ ‘Are you taking into account data that are different from what I have considered?’ (p. 186)

In other words, look at the data that gives rise to the stories you tell yourself, and then ask if there’s another way to interpret the data. By seeking out different ways to interpret data, it helps you keep an open mind and stay unattached to your views. (If there was ever a golden principle that helps relationships stay healthy, it’s this principle about mental models.)

5. Take risks

The final recommendation is perhaps the hardest: take risks. I’m a cautious person in most areas of my life, from driving to sports, finances, and more. When I worked at Amazon for nearly 5 years, I could feel that I was starting to get too comfortable. Things were becoming automatic for me. I felt like I could stay in my position for 10-15 years.

Even though it was uncomfortable, I decided to take a big leap by not only switching to a new company (Google) but also relocating to a new state (from California to Washington). We even bought a house we’d never actually seen in person! It all worked out, fortunately.

Why does taking risks keep us young? Think of the analogy to company innovation. Clay Christiansen talks about why big companies, thriving and dominant for a time, can suddenly be overtaken by a much smaller company. The reason? The large, established company invests in sustaining innovations (small improvements to their existing technology), while the smaller company operates in stealth mode and takes a swing at disruptive innovations. Eventually, the disruptive innovations hit a maturity point and put the larger company out of business (think about Netflix and Blockbuster). I wrote a series of posts about this here: Sustaining and disruptive innovations.

Our careers operate in the same way. It’s easier to make small improvements, but sometimes the disruptive innovations in our lives can yield large improvements. For example, my API doc course was a tremendous success from many points of view (workshops, advertising, feedback from others). But at the start of this year, as I reflected on the previous year, I realized I wanted to double down on some writing projects and techniques that I’ve been thinking about for years. I want to write essays following a common theme, and connect those essays together into published books. The time required to do this, however, would mean less time devoted to my API doc site maintaining and improving the content there. I decided to take the risk of devoting 2022 to seeing these projects through. I have three series I’m working on:

- Trends to follow or forget

- Journey away from smartphones

- A hypothesis about influence on the web and the workplace

It’s now August and I’m hoping to bring at least one of the series to completion by the year’s end. I’ll dig back into my API course a bit later in the year, probably.

Before finishing this section, I want to conclude with one of my favorite quotes. Picasso said, “It takes a long time to become young.” The ability to read constantly, experiment regularly, ask questions, and take risks involves lifelong attributes to develop and cultivate.

Avoid becoming Jayden

Meet Jayden! Jayden has two years of experience. He recently graduated from college and even had an internship. He’s new, so he’s still learning a lot. But in his current state, he needs a lot of hand-holding.

Jayden mostly waits for tickets to be assigned to him. If no one assigns him tickets, he doesn’t seek out the work. As a junior writer, he mostly operates in listen-only mode. He has good writing skills, but he needs most of the information collected for him. He has a hard time reaching out to different stakeholders to set up meetings and pull information from engineers’ heads. Jayden has a fun personality and people enjoy chatting with him, but he requires a lot of management to be productive. Jayden is still operating in novice mode.

Five ways to level up past novice mode

To level up past novice mode (and avoid becoming Jayden), I recommend five strategies:

- Be proactive rather than reactive

- Develop the mental skills to focus

- Stop expecting reviewers to read docs on their own

- Specialize your skillset

- Use writing to influence stakeholders

I’ll expand on each technique in the sections below.

1. Be proactive rather than reactive

The first strategy is to shift from being reactive to proactive. This shift, I’m convinced, is the core principle of leadership.

As a concrete example, think about your doc tasks. How do you figure out what doc work needs to be done, without your manager telling you? I recommend setting up biweekly meetings with two general groups: each product team that you support, and the partner engineering (devrel) group that interacts with partners. (The name of this “partner engineering” group varies by company — just find whoever interacts with your users, and meet with this group.) These two groups will help identify the doc work for you.

When working with product groups, ask for their roadmaps, as this will give you a clear idea about what’s on the horizon (rather than being informed at the last minute). With partner engineering groups, look at the incoming tickets to help identify trends and start conversations about the work that needs to be done. These two information sources can help define the agendas for these meetings.

When you set up a biweekly rhythm like this, meeting regularly with these two groups, you’ll have a clear sense of the needed documentation work and won’t need to rely on others, especially your manager, to define what needs to be done.

Proactivity extends beyond just discovering the doc work, of course. When you take action without being asked or assigned the task, you’re leveling up past novice mode. There are many ways to do this.

2. Develop the mental skills to focus

Social media, from Slack to Twitter, Reddit, Youtube, and more, makes us feel connected and in step with the latest information and trends. But with that sense of connection comes the risk of attention fragmentation and constant distraction. My entire series on smartphones dives into this topic in extensive ways. If you can’t mute the distractions around you, you’ll struggle to enter into deep focus modes that allow for sustained productivity.

Without sustained focus, you’ll be unlikely to make much progress against projects. You might find that you’re constantly interacting in chat, email, social media, and other channels all day, feeling busy, but not making much progress on projects.

Here are a few tips to develop focus. Put your phone on Do Not Disturb mode (except for family notifications), and try to carry the phone in your bag more than your pocket. Remove work email from your phone (but not your work calendar). Turn off instant Slack notifications and email/chat notifications that will pull you out of the moment. Consider using the Pomodoro technique to set 20-minute sessions of focused work.

In general, experiment with ways to focus that will make you productive. The people around you don’t need immediate responses. You’re a technical writer, not an emergency room doctor. Read Cal Newport’s Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World for more concrete and powerful strategies for focus.

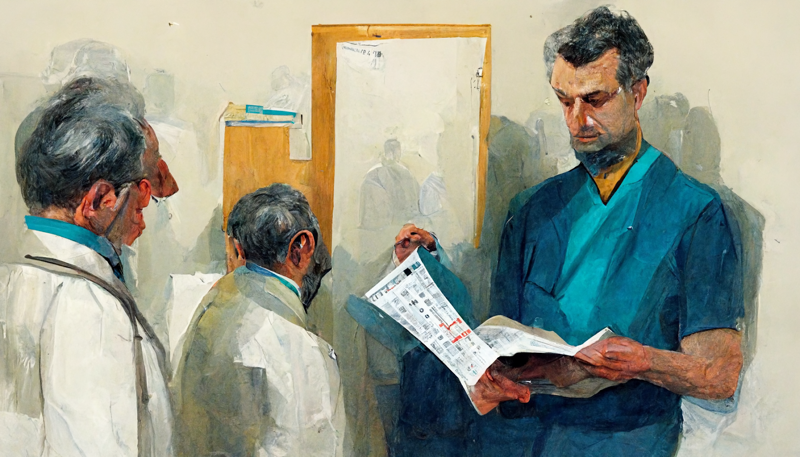

3. Stop expecting reviewers to read docs on their own

As a beginning writer, I thought I could send an email to a relevant stakeholder group asking them to review a doc, and they would review it on their own time. I was surprised when no one responded. It took years before I fully abandoned this method.

We all need input from reviewers (engineers, product managers, partner engineers, and other stakeholders) on the documentation we’re writing to bring it up to production quality. Rather than ping people to review content asynchronously like I initially did, bake in time for people to read the document during the review meetings.

Seriously, when you begin the review meeting, give people the option to silently read the document for the first 20 minutes. Most of the time, reviewers will prefer to comment as they read. If so, I tell reviewers to vocalize their feedback while I take notes. This allows them to make much faster progress through the document. This review technique is one I learned while at Amazon (see Matching documentation review practices to company culture for more details).

Based on years of tested experience, I’ve found that this approach works. It ensures that people review your content, allowing you to meet deadlines and other release timelines for your content.

This approach might seem awkward or odd at first, and it can feel like you’re babysitting someone through tasks they can do on their own. But in my experience, few people read docs outside of review meetings. If they do, their reading is usually cursory. If you have multiple reviewers in the same meeting, it’s guaranteed that some will have read the material outside the meeting while others won’t have. Then you have to either wait for those who haven’t read the doc to read it, frustrating those who have. Or you’ll have to skip the unprepared reviewers from reading and giving feedback. In short, it’s just much easier to give everyone time to read the material during the review meeting.

This technique might seem pretty specific, but it connects with a larger principle of documentation quality and excellence. Too often, earlier in my career I would try to write everything myself, independently, by playing with the application, looking at the code, and learning through trial and error. As I got older, I realized that good writing gathers input and feedback from a large collection of people.

4. Specialize your skillset

As you gain more experience, you’ll inevitably gravitate toward some kind of specialization within the tech comm field. This specialization helps you sustain interest in the career long term, and it brands your professional expertise.

Some example areas of specialization include the following:

- API documentation

- Developer portals

- Developer UX

- Style guides

- Tools

- Usability

- eLearning

- Management

- Intelligent Content

- Consulting

- Content management systems

- Cross-product collaboration

- Video production

- Graphic design and illustration

Beyond rejuvenating your career with added interest, specialization also makes you more marketable. By itself, writing is often seen as a commodity. Career experts like Jack Molisani, who runs Lavacon and a tech comm staffing agency, recommend making your job title a hybrid (for example, a tech writer / usability expert, a tech writer / content management expert) to be much more attractive to employers.

But besides the career benefits of specialization, it just makes the tech comm career more engaging. About 10 years ago, I found that I actually liked working with API documentation and developer portals. I discovered that the realm of developer docs (where APIs and dev portals abound) was a rich, unexplored landscape that led me to develop an entire course on the topic: API documentation. This focus rejuvenated my career.

5. Use writing to influence stakeholders

My final tip is to use writing (your superpower) to influence stakeholders. We often don’t recognize how influential writing can be, but if I’ve learned anything from blogging, it’s that the formula for influence is rather simple: write and share, repeatedly.

I’ve always been amazed by how visible I’ve become in tech comm circles. People across the globe seem to know me. How can you reproduce the same visibility techniques inside a corporation to achieve a similar effect? This is the focus of my series A hypothesis about influence on the web and the workplace. To use writing in a way that influences stakeholders inside a company, try these three tips:

- Type of notes of meetings and distribute them to wider channels

- Send out newsletters detailing the documentation work going on

- Start a book club and share details about domain-focused, relevant books

When you share content regularly, your name will become more well-known. When people think of docs, they’ll think of you. That association can make you a more relevant presence in the organization.

Conclusion

I realize that I initially focused on generalizations about years of experience that are behavior extremes. Truth be told, the first half — how to avoid becoming Jerry — is written primarily for me, as this has been a growing fear of mine for some time. My whole point is that we can avoid becoming either Jerry or Jayden. I want to be the 60-year-old technical writer that all young engineers specifically request for their projects. I’m convinced that, no matter your age, when people get to know you, when they sense your curiosity, passion to experiment and try new things, when they see how you question even your own long-held assumptions and can shift to other points of view, the wrinkles on your skin won’t matter.

In the same way, if you’re just starting out and barely know how to find the supply room at work, but you know how to discover the work that needs to be done, how to define the doc work (through biweekly meetings with stakeholders), how to make progress toward large documentation projects (through sustained focus), and how to get information from engineers (through effective doc reviews), people will look past your age and inexperience. You’ll be seen as a vital member of the team and a project leader.

In conclusion, age is neither an asset nor a liability. What matters are the characteristics and behaviors you embrace. Keep these principles in mind whether you’re just starting out or whether you’re on the last leg of your career journey.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.