API status and error codes

Status and error codes refer to a code number in the response header that indicates the general classification of the response — for example, whether the request was successful (200), resulted in a server error (500), had authorization issues (403), and so on. Standard status codes don’t usually need much documentation, but custom status and error codes specific to your API do. Error codes in particular help in troubleshooting bad requests.

- Sample status code in curl header

- Where to list the HTTP response and error codes

- Where to get status and error codes

- How to list status codes

- Status/error codes can assist in troubleshooting

- Example of status and error codes

- Activity with status and error codes

Sample status code in curl header

Status codes don’t appear in the response body. They appear in the response header, which you might not see by default.

Remember when you submitted the curl call back in Make a curl call? To get the response header, you add --include or -i to the curl request. If you want only the response header returned in the response (and nothing else), capitalize the -I, like this:

curl -I -X GET "https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?zip=95050&appid=APIKEY&units=imperial"

Replace APIKEY with your actual API key.

The response header looks as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: openresty

Date: Thu, 06 Dec 2018 22:58:41 GMT

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 446

Connection: keep-alive

X-Cache-Key: /data/2.5/weather?units=imperial&zip=95050

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST

The first line, HTTP/1.1 200 OK, tells us the status of the request (200). Most REST APIs follow a standard protocol for response headers. For example, 200 isn’t just an arbitrary code decided upon by the OpenWeatherMap API developers. 200 is a universally accepted code for a successful HTTP request. (If you change the method, you’ll get back a different status code.)

With a GET request, it’s pretty easy to tell if the request is successful because you get back the expected response. But suppose you’re making a POST, PUT, or DELETE call, where you’re changing data contained in the resource. How do you know if the request was successfully processed and received by the API? HTTP response codes in the header of the response will indicate whether the operation was successful. The HTTP status codes are just abbreviations for longer messages.

All too often, status codes are uninformative, poorly written, and communicate little or no helpful information to the user to overcome the error. Ultimately, status codes should assist users in recovering from errors.

You can see a list of common REST API status codes here and a general list of HTTP status codes here. Although it’s probably good to include a few standard status codes, comprehensively documenting all standard status codes, especially if rarely triggered by your API, is unnecessary.

Where to list the HTTP response and error codes

Most APIs should have a general page listing response and error codes across the entire API. A standalone page listing the status codes (rather than including these status codes with each endpoint) allows you to expand on each code with more detail without crowding the other documentation. It also reduces redundancy and the sense of information overload.

On the other hand, if some endpoints are prone to triggering certain status and error codes more than others, it makes sense to highlight those status and error codes on same API reference pages. One strategy might be to call attention to any particularly relevant status or error codes for a specific endpoint, and then link to the centralized “Response and Status Codes” page for full information.

Where to get status and error codes

Status and error codes may not be readily apparent when you’re documenting your API. You’ll probably need to ask developers for a list of all the status and error codes that are unique to your API. Sometimes developers hard-code these status and error codes directly in the programming code and don’t have easy ways to hand you a comprehensive list (this makes localization problematic as well).

As a result, you may need to experiment a bit to ferret out all the codes. Specifically, you might need to try to break the API to see all the potential error codes. For example, if you exceed the rate limit for a specific call, the API might return a special error or status code. You would especially need to document this custom code. A troubleshooting section in your API might make special use of the error codes.

How to list status codes

You can list your status and error codes in a basic table or definition list, somewhat like this:

| Status code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 200 | Successful request and response. |

| 400 | Malformed parameters or other bad request. |

Status/error codes can assist in troubleshooting

Status and error codes can be particularly helpful when it comes to troubleshooting. As such, you can think of these error codes as complementary to a section on troubleshooting.

Almost every set of documentation could benefit from a section on troubleshooting. In a troubleshooting topic, you document what happens when users get off the happy path and stumble around in the dark forest. Status codes are like the poorly illuminated trail signs that will help users get back onto the right path.

A section on troubleshooting could list error messages related to the following situations:

- The wrong API keys are used

- Invalid API keys are used

- The parameters don’t fit the data types

- The API throws an exception

- There’s no data for the resource to return

- The rate limits have been exceeded

- The parameters are outside the max and min boundaries of what’s acceptable

- A required parameter is absent from the endpoint

Where possible, document the exact text of the error in the documentation so that it easily surfaces in searches.

Example of status and error codes

The following are some sample status and error code pages in API documentation.

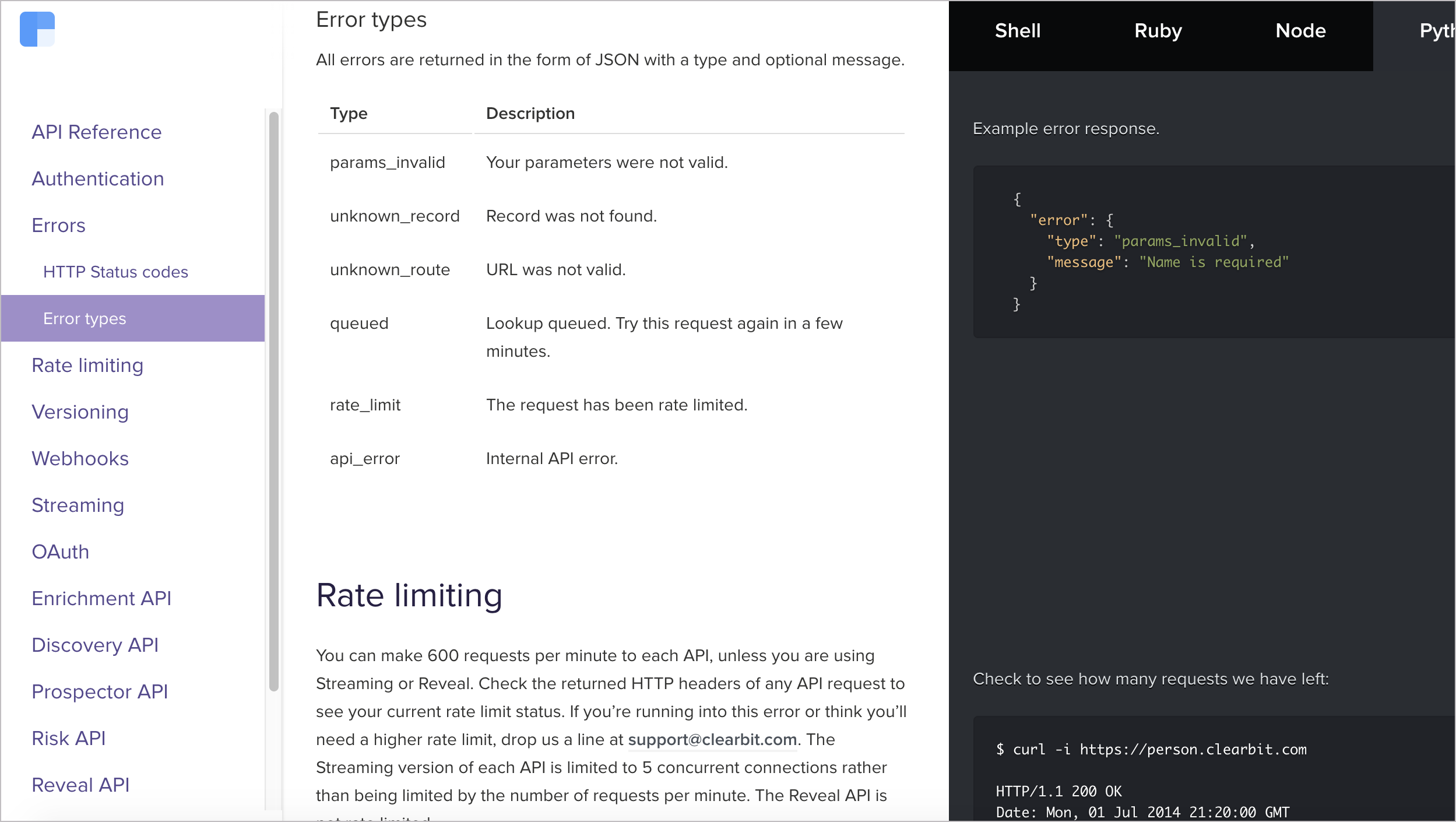

Context.io

Clearbit not only documents the standard status codes but also describes the unique parameters returned by their API. Most developers will probably be familiar with 200, 400, and 500 codes, so these codes don’t need a lot of explanatory detail. But if your API has unique codes, make sure to describe these adequately.

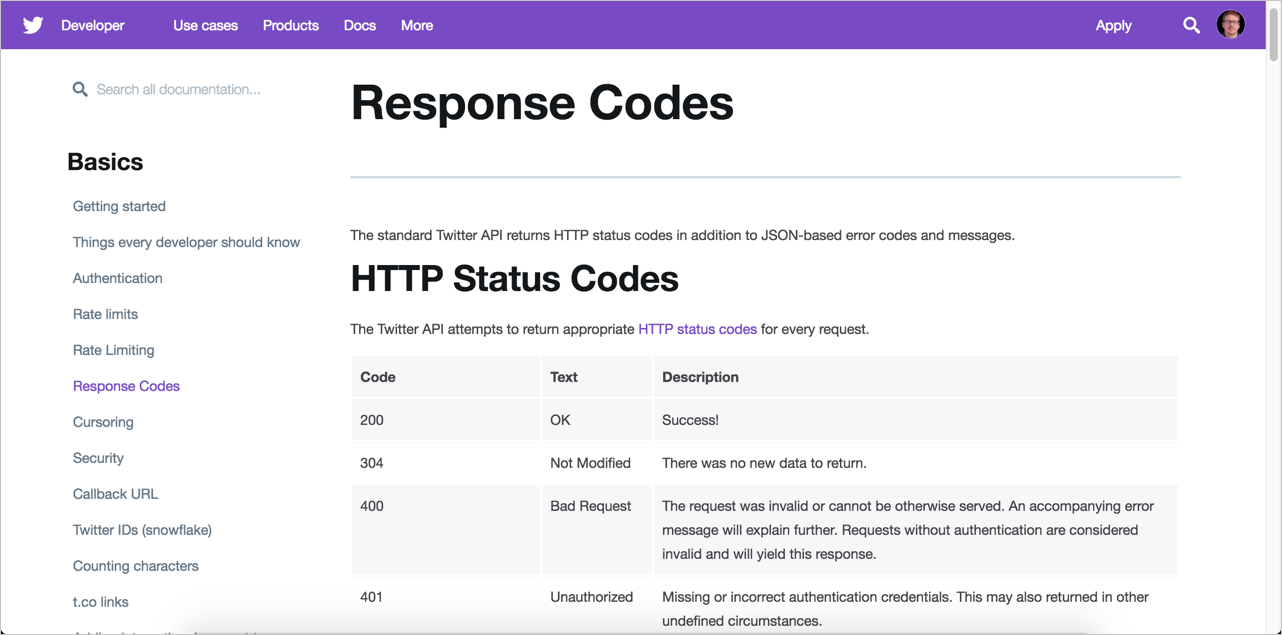

With Twitter’s status code documentation, they not only describe the code and status but also provide helpful troubleshooting information, potentially assisting with error recovery. For example, with the 500 error, the authors don’t just say the status refers to a broken service, they explain, “This is usually a temporary error, for example in a high load situation or if an endpoint is temporarily having issues. Check in the developer forums in case others are having similar issues, or try again later.”

This kind of helpful message is what tech writers should aim for with status codes (at least for those codes that indicate problems).

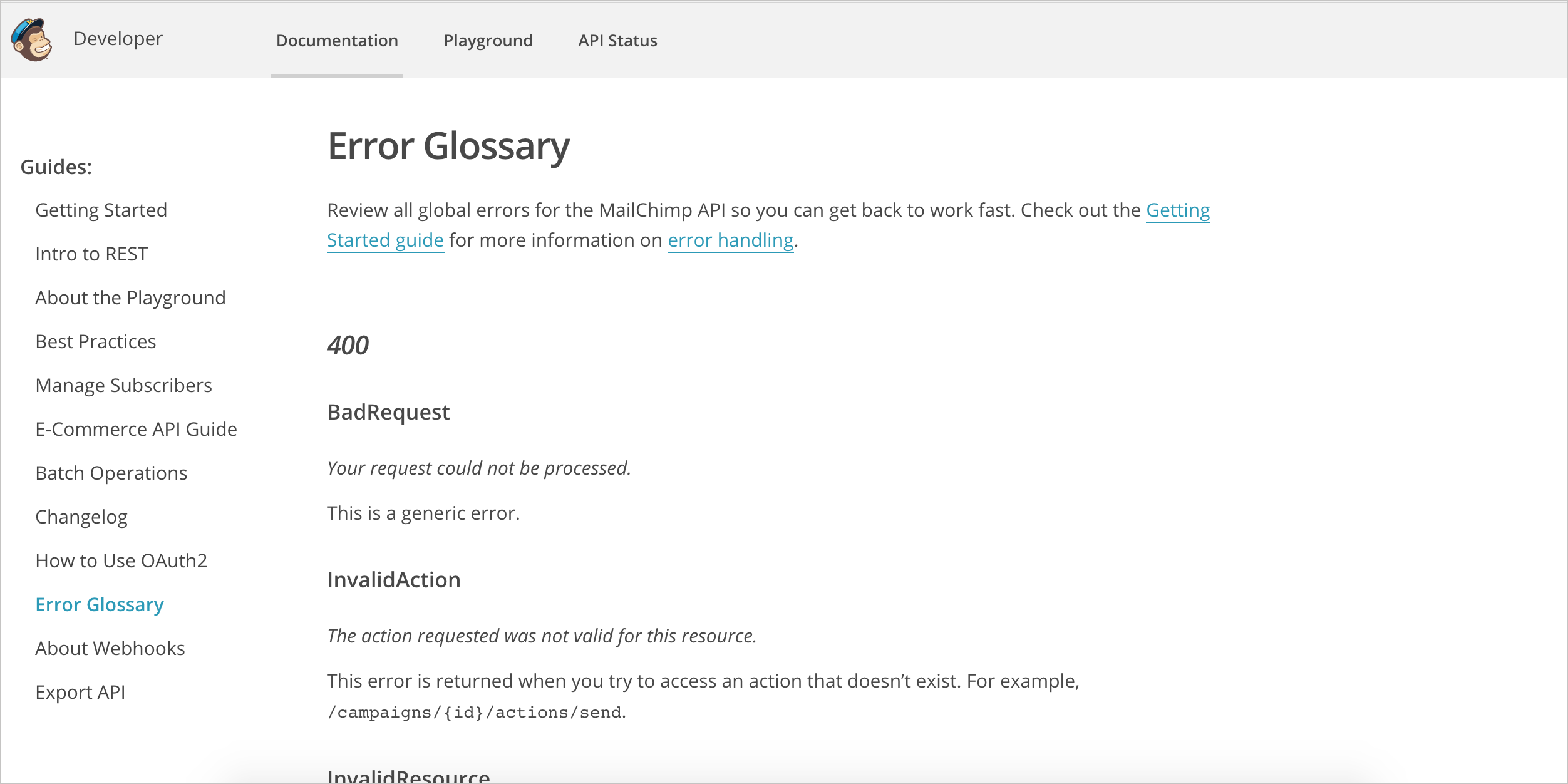

Mailchimp

Mailchimp provides readable and friendly descriptions of the error message. For example, with the 403 errors, instead of just writing “Forbidden,” Mailchimp explains reasons why you might receive the Forbidden code. With Mailchimp, there are several types of 403 errors. Your request might be forbidden due to a disabled user account or request made to the wrong data center. For the “WrongDataCenter” error, Mailchimp notes that “It’s often associated with misconfigured libraries” and they link to more information on data centers. This is the type of error code documentation that is helpful to users.

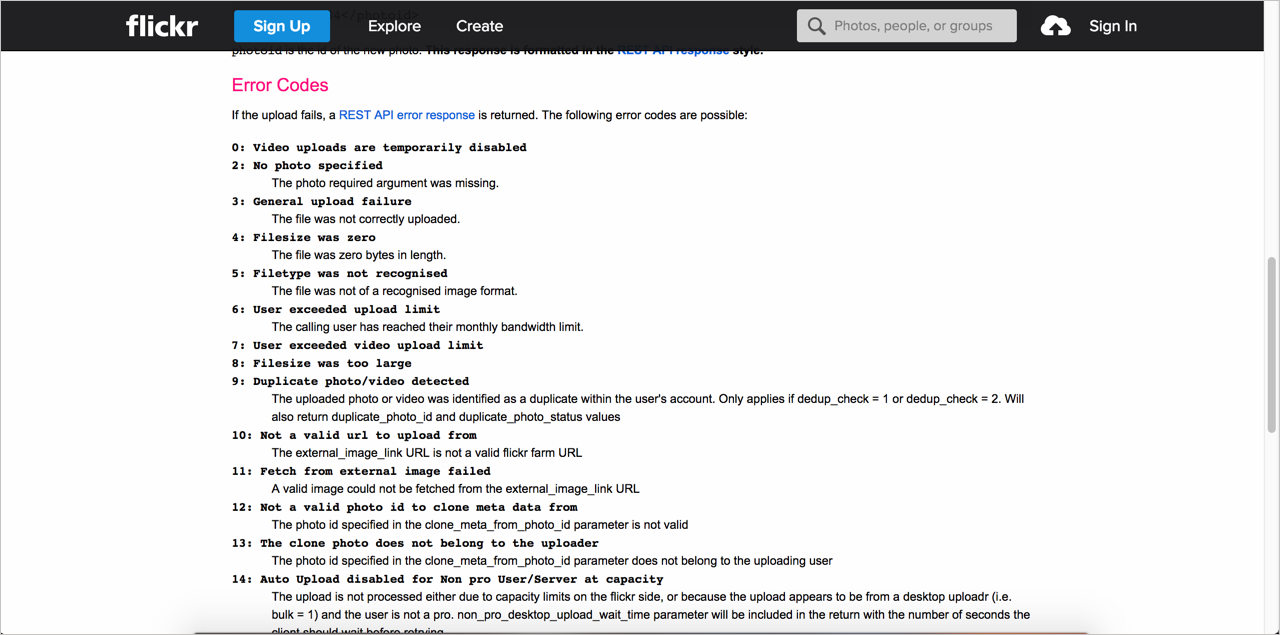

Flickr

With Flickr, the Response Codes section is embedded within each API reference topic. As such, the descriptions are short. While embedding the Response Codes in each topic makes the error codes more visible, in some ways it’s less helpful. Because it’s embedded within each API topic, the descriptions about the error codes must be brief, or the content would overwhelm the endpoint request information.

In contrast, a standalone page listing error codes allows you to expand on each code with more detail without crowding out the other documentation. The standalone page also reduces redundancy and the appearance of a heavy amount of information (information which is just repeated).

If some endpoints are prone to triggering certain status and error codes more than others, it makes sense to highlight those status and error codes on their relevant API reference pages. I recommend calling attention to any particularly relevant status or error codes on an endpoint’s page and then linking to the centralized page for full information.

Activity with status and error codes

With the open-source project you identified, identify the status and error code information. Answer the following questions:

- Does the project describe status and error codes?

- Where is the status and error code information located within the context of the documentation? As a standalone topic? Below each endpoint? Somewhere else?

- Does the API have any unique status and error codes?

- Do the error codes help users recover from errors?

- Make a request to one of the endpoints. Then purposefully change a parameter so that it invalidates the call. What status code gets returned in the response? Is this status code documented?

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

73/168 pages complete. Only 95 more pages to go.