Retrieve a gallery using the Flickr API

Use the Flickr API to get photo images from this Flickr gallery.

- Flickr Overview

- 1. Get an API key to make requests

- 2. Determine the resource and endpoint you need

- 3. Construct the request

- 4. Analyze the response

- 5. Pull out the information you need

- Final Result

Flickr Overview

In this Flickr API example, we want to get all the photos from a specific Flickr gallery called Color in Nature and display them on a web page. Here’s the gallery we want:

To achieve our goal, we’ll need to call several endpoints. Hopefully, this activity will demonstrate the shortcomings of just having reference documentation. When one endpoint requires another endpoint response as an input, you might have to communicate these workflows through tutorials.

1. Get an API key to make requests

Before you can make a request with the Flickr API, you’ll need an API key, which you can read more about here. When you register an app, you’re given a key and secret.

2. Determine the resource and endpoint you need

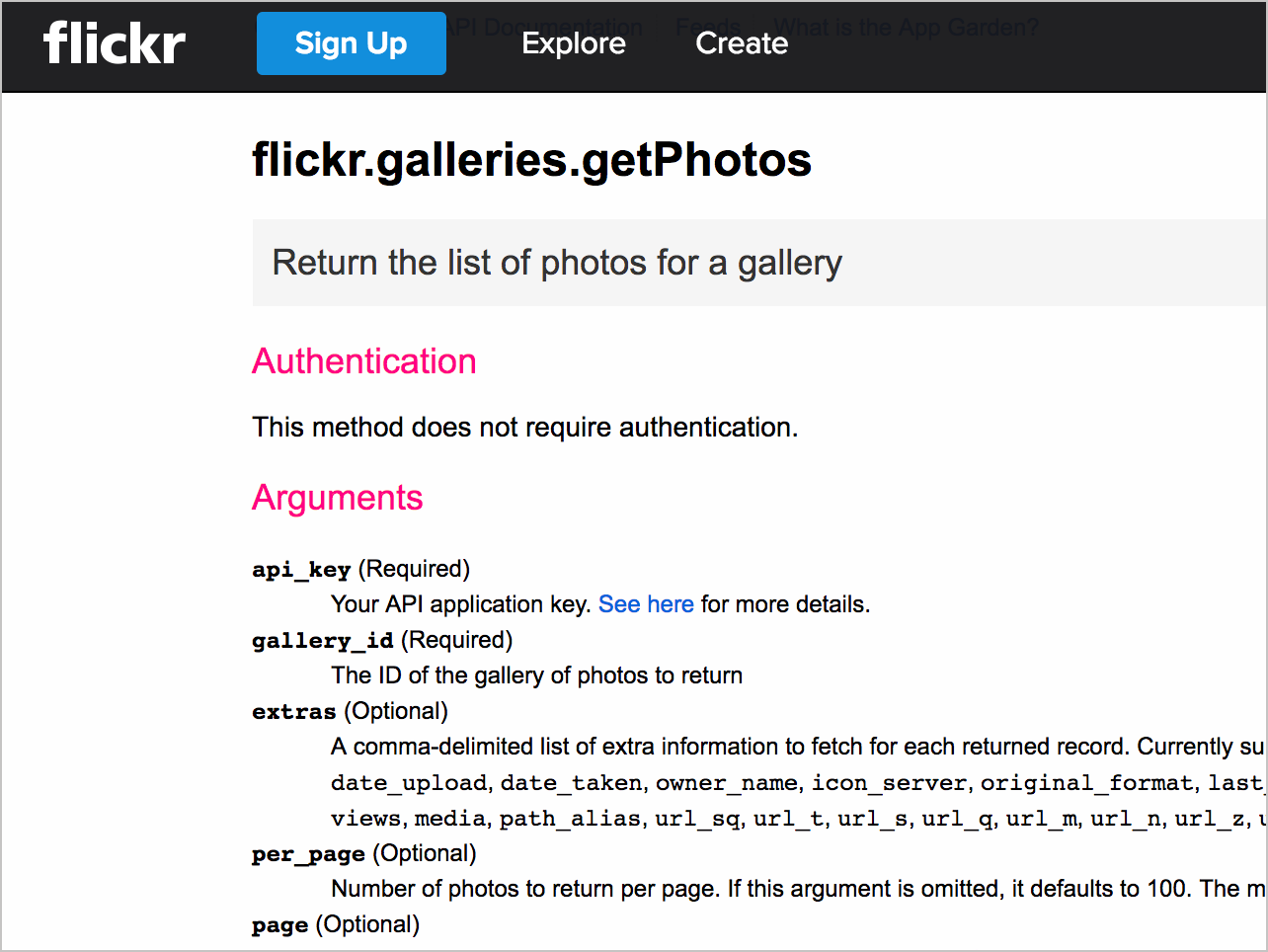

From the list of Flickr’s API methods, the flickr.galleries.getPhotos endpoint, which is listed under the galleries resource, is the one that will get photos from a gallery.

One of the arguments we need for the getPhotos endpoint is the gallery_id. Before we can get the gallery_id, however, we have to use another endpoint to retrieve it. Somewhat unintuitively, the gallery_id is not the ID that appears in the URL of the gallery.

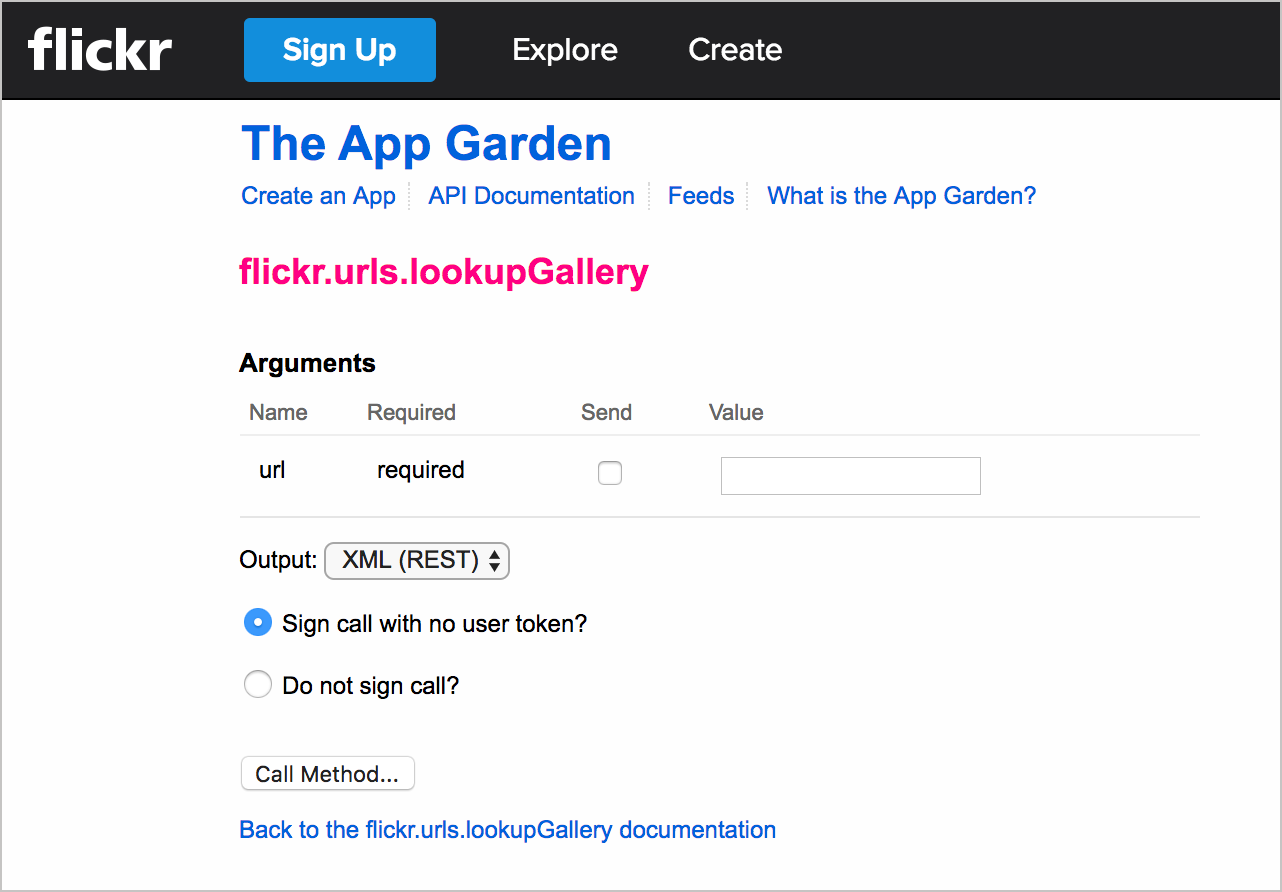

Instead, we use the flickr.urls.lookupGallery endpoint listed in the URLs resource section to get the gallery_id from a gallery URL:

The gallery_id for Color in Nature is 66911286-72157647277042064. We now have the arguments we need for the flickr.galleries.getPhotos endpoint.

3. Construct the request

We can make the request to get the list of photos for this specific gallery_id.

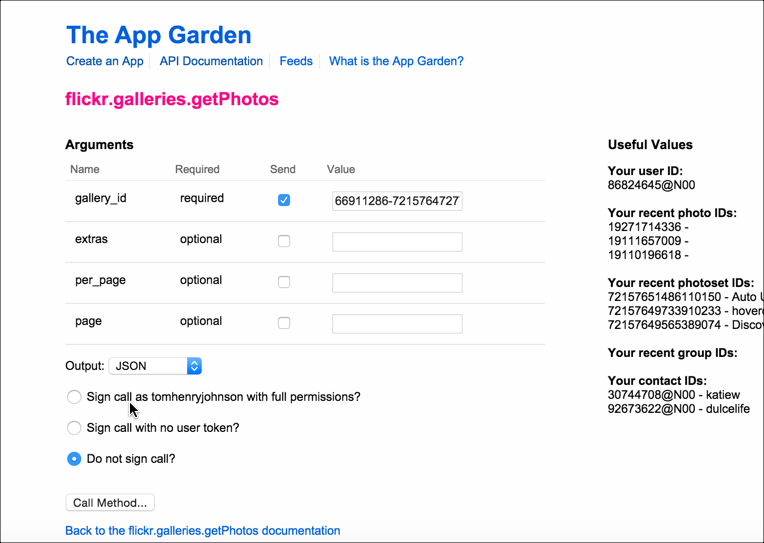

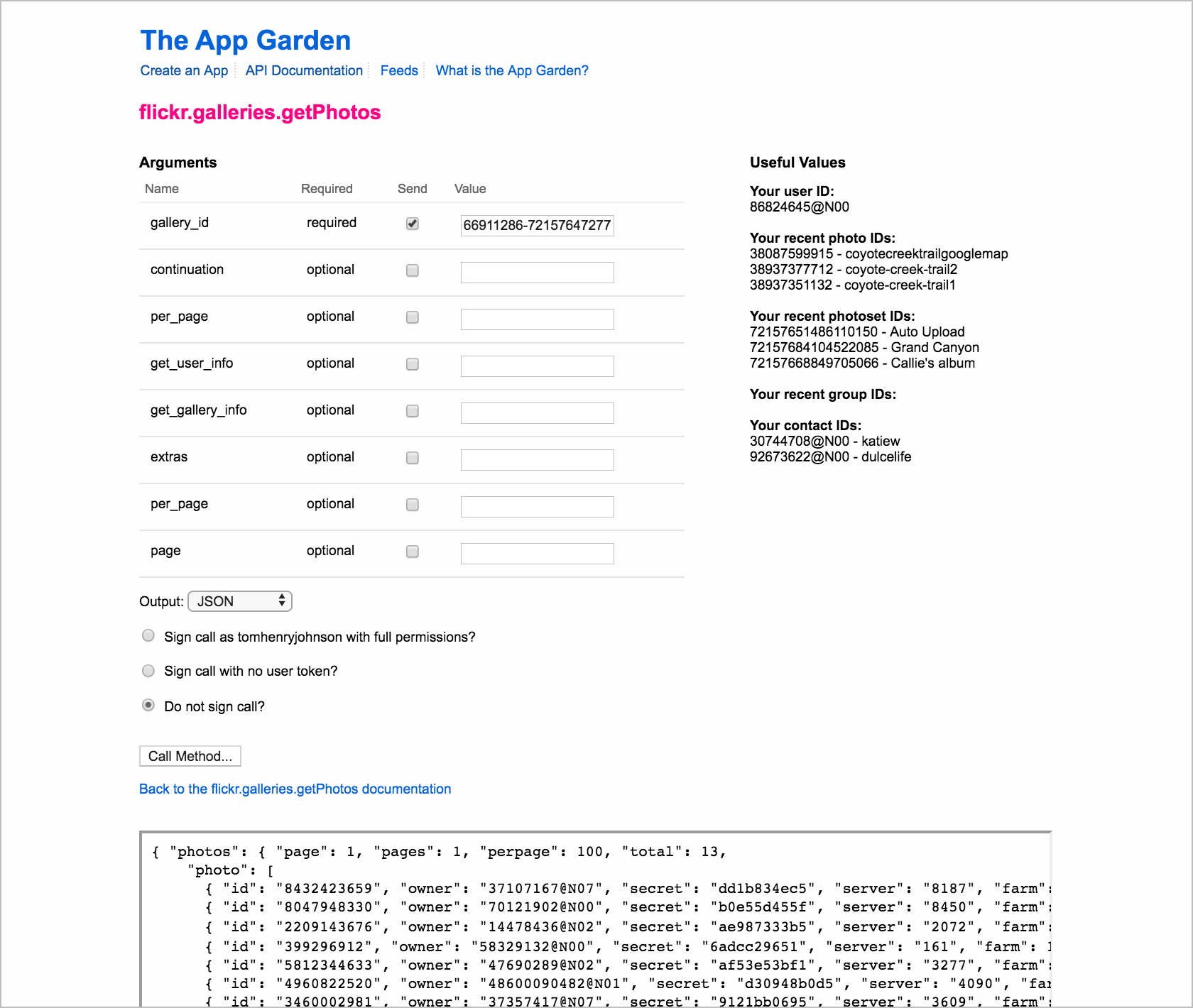

Flickr provides an API Explorer to simplify calls to the endpoints. If we go to the API Explorer for the galleries.getPhotos endpoint, we can plug in the gallery_id and see the response, as well as get the URL syntax for the endpoint.

Insert the gallery_id, select JSON for the output, select Do not sign call (we’re just testing here, so we don’t need extra security), and then click Call Method.

Here’s the result:

The URL below the response shows the right syntax for using this method:

https://api.flickr.com/services/rest/?method=flickr.galleries.getPhotos&api_key=APIKEY&gallery_id=66911286-72157647277042064&format=json&nojsoncallback=1

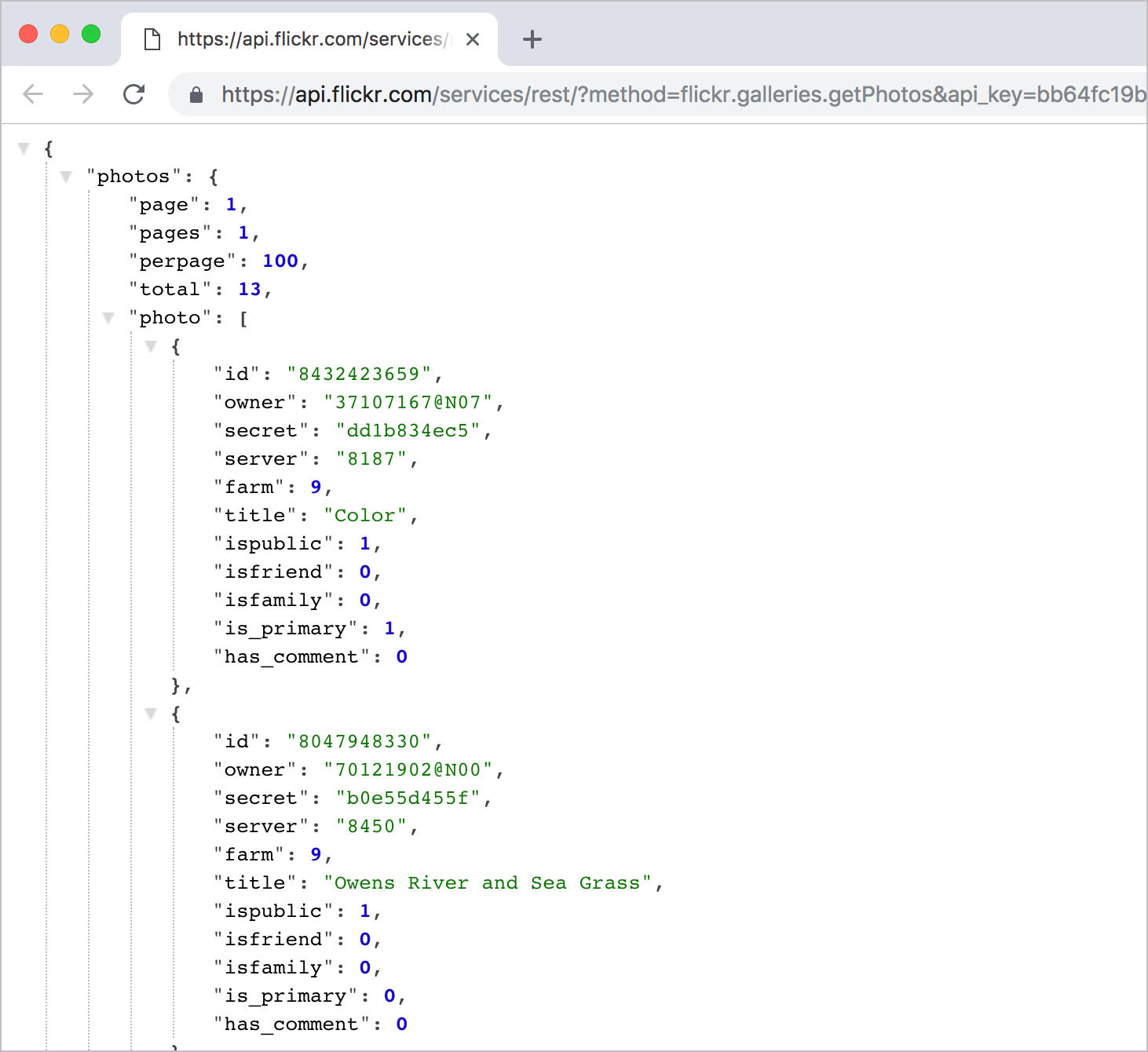

If you submit the request directly in your browser using the given URL, you can see the same response but in the browser rather than the API Explorer:

I’m using the JSON Formatting extension for Chrome to make the JSON response more readable. Without this plugin, the JSON response is compressed.

4. Analyze the response

All the necessary information is included in this response in order to display photos on our site, but it’s not entirely intuitive how we construct the image source URLs from the response.

In other words, the information a user needs to achieve a goal isn’t explicit in the API reference documentation. The reference docs explain only what’s returned in the response, not how to actually use the response.

The Photo Source URLs page in the documentation explains it:

You can construct the source URL to a photo once you know its ID, server ID, farm ID, and secret, as returned by many API methods.

The URL takes the following format:

https://farm{farm-id}.staticflickr.com/{server-id}/{id}_{secret}.jpg

or

https://farm{farm-id}.staticflickr.com/{server-id}/{id}_{secret}_[mstzb].jpg

or

https://farm{farm-id}.staticflickr.com/{server-id}/{id}_{o-secret}_o.(jpg|gif|png)

Here’s what an item in the JSON response looks like:

{

"photos": {

"page": 1,

"pages": 1,

"perpage": 100,

"total": 13,

"photo": [

{

"id": "8432423659",

"owner": "37107167@N07",

"secret": "dd1b834ec5",

"server": "8187",

"farm": 9,

"title": "Color",

"ispublic": 1,

"isfriend": 0,

"isfamily": 0,

"is_primary": 1,

"has_comment": 0

},

...

]

}

}

You access these fields through dot notation. It’s a good idea to log the whole object to the console just to explore it better.

5. Pull out the information you need

The following code uses jQuery to loop through each of the responses and inserts the necessary components into an image tag to display each photo.

<html>

<style>

img {max-height:125px; margin:3px; border:1px solid #dedede;}

</style>

<body>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

var settings = {

"async": true,

"crossDomain": true,

"url": "https://api.flickr.com/services/rest/?method=flickr.galleries.getPhotos&api_key=APIKEY&gallery_id=66911286-72157647277042064&format=json&nojsoncallback=1",

"method": "GET",

"headers": {}

}

$.ajax(settings).done(function (data) {

console.log(data);

$("#galleryTitle").append(data.photos.photo[0].title + " Gallery");

$.each( data.photos.photo, function( i, gp ) {

var farmId = gp.farm;

var serverId = gp.server;

var id = gp.id;

var secret = gp.secret;

console.log(farmId + ", " + serverId + ", " + id + ", " + secret);

// https://farm{farm-id}.staticflickr.com/{server-id}/{id}_{secret}.jpg

$("#flickr").append('<img src="https://farm' + farmId + '.staticflickr.com/' + serverId + '/' + id + '_' + secret + '.jpg"/>');

});

});

</script>

<h2><div id="galleryTitle"></div></h2>

<div style="clear:both;"/>

<div id="flickr"/>

</body>

</html>

Here’s what the code is doing:

- In this code, the ajax method from jQuery gets the JSON payload. The payload is assigned to the

dataargument and then logged to the console. - The data object contains an object called

photos, which contains an array calledphoto. Thetitlefield is a property in an object in thephotoarray. Thetitleis accessed through this dot notation:data.photos.photo[0].title. - To get each item in the object, jQuery’s each method loops through an object’s properties. Note that jQuery

eachmethod is commonly used for looping through results to get values. For the first argument (data.photos.photo), you identify the object that you want to access. For thefunction( i, gp )arguments, you list an index and value. You can use any names you want here.gpbecomes a variable that refers to thedata.photos.photoobject you’re looping through.irefers to the starting point through the object. (You don’t need to refer toibeyond the instance here unless you want to begin or end the loop at a certain point.) - To access the properties in the JSON object, we use

gp.farminstead ofdata.photos.photo[0].farm, becausegpis an object reference todata.photos.photo[i]. - After the

eachfunction iterates through the response, I added some variables to make it easier to work with these components (usingserverIdinstead ofgp.server, etc.). And aconsole.logmessage checks to ensure we’re getting values for each of the elements we need. - This comment shows where we need to plug in each of the variables:

// https://farm{farm-id}.staticflickr.com/{server-id}/{id}_{secret}.jpg

The final line shows how you insert those variables into the HTML:

$("#flickr").append('<img src="https://farm' + farmId + '.staticflickr.com/' + serverId + '/' + id + '_' + secret + '.jpg"/>');

A common pattern in programming is to loop through a response. This code example used the each method from jQuery to look through all the items in the response and do something with each item. Sometimes you incorporate logic that loops through items and looks for certain conditions present to decide whether to take some action. Pay attention to methods for looping, as they are common scenarios in programming.

For more information, see these topics:

- Inspect the JSON from the response payload[](docapis_json_console.html)

- Access and print a specific JSON value

- Dive into dot notation

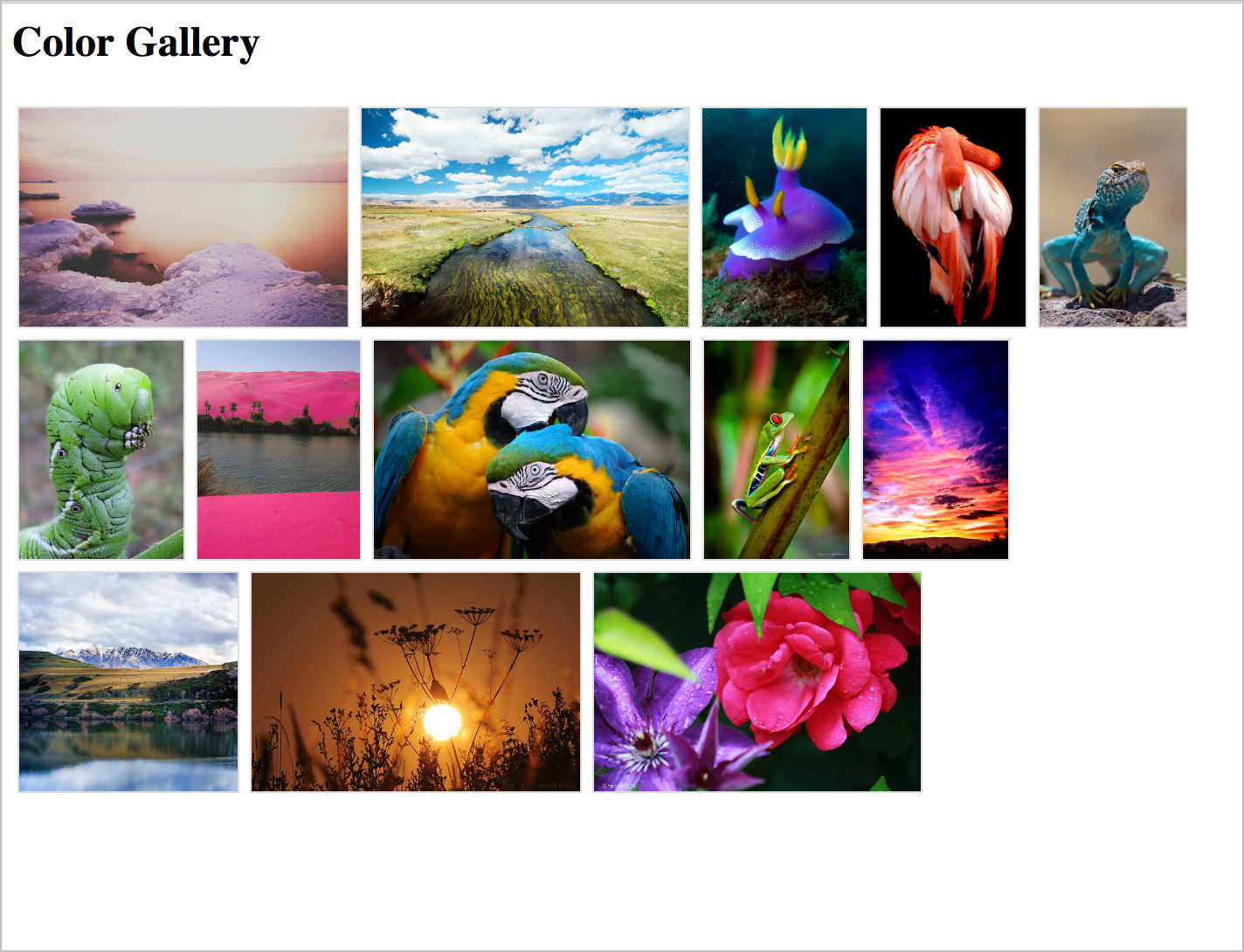

Final Result

You can view a demo of the Color Gallery integration here.

The result looks like this:

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

161/168 pages complete. Only 7 more pages to go.