Different approaches for assessing information quality

In the previous topic, Measuring documentation quality through user feedback, I explained the challenges of getting feedback from user surveys as a way to measure documentation quality. In this section, I’ll survey the landscape on criteria and rubrics for assessing documentation quality.

- Common categories for information quality

- The problem with abstract definitions

- Other research

- Technical writing handbooks

- Standards specifications

- Other sources for quality

Common categories for information quality

Documentation quality is generally assessed against the following criteria:

- Readability

- Clarity

- Context

- Accuracy

- Organization

- Succinctness

- Completeness

- Findability

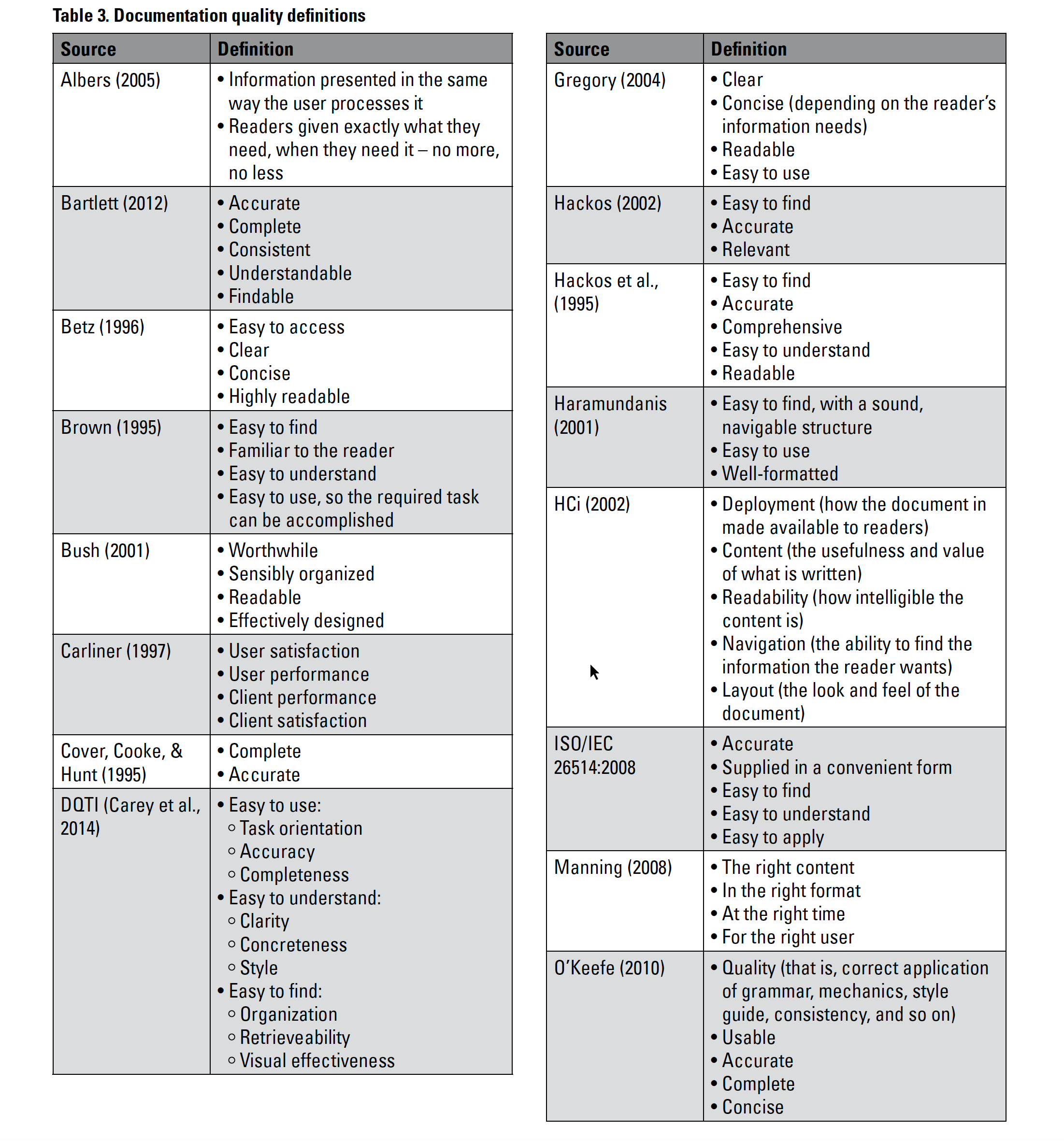

In Beyond Accuracy: What Documentation Quality Means to Readers, Yoel Strimling looks at previous research on the attempt to define information quality and finds a wide range of different quality definitions:

As you can see, defining information quality is a constant theme in tech comm research. While the characteristics are somewhat similar, they aren’t described in the same way, and they are mostly general and abstract. Troubled by the lack of a unified approach to documentation quality, and by the slipperiness of terms and lack of consistency, Strimling asks, which of these qualities matter most to users?

Strimling aligns with researchers Richard Wang and Diane Strong (1996) because of the way their research aligns with the “voice of the data customer” and because of the soundness of their framework and research. Wang and Strong’s research is the foundation for many other articles here as well. After describing 118 information quality dimensions, Wang and Strong boil them down to four main criteria. Yoel explains:

Based on their categories, Wang and Strong (1996) concluded that high-quality data must be:

- Intrinsically good

- Contextually appropriate for the task

- Clearly represented

- Accessible to the consumer

You can read the original article by Wang and Strong in the Journal of Management Information Systems if you have access to it, or online here. These researchers made a pivot in how they measured data quality — rather than considering the accuracy of the information on its own, they looked to see what aspects were important to users, and factored that user perspective into the quality assessment. They explain:

The salient feature of this research study is that quality attributes of data are collected from data consumers instead of being defined theoretically or based on researchers’ experience.

In other words, you can’t measure data quality (DQ) without analyzing what quality dimensions are important to users. In their research, they settled on the four criteria that Strimling summarized:

[Intrinsic DQ] The extent to which data values are in conformance with the actual or true values;

[Contextual DQ] The extent to which data are applicable (pertinent) to the task of the data user;

[Representational DQ] The extent to which data are presented in an intelligible and clear manner and

[Accessibility DQ] The extent to which data are available or obtainable.

Wang and Strong’s emphasis is on data quality, not necessarily documentation. Building on Wang and Strong, Strimling identifies 15 different dimensions to documentation quality and then asks users to rate them by importance. He concluded that these four categories are most important to users: accurate, relevant, easy to understand, accessible. These criteria are based on the level of importance assigned to them by the readers who participated in his study. He proposes that you can measure quality by asking users these four questions:

- Could you find the information you needed in the document?

- Was the information in the document accurate?

- Was the information in the document relevant?

- Was the information in the document easy to understand?

Strimling says you can ask users these questions during various interaction points (doc surveys, training situations, support interactions, onboarding, and more). The questions aren’t simply yes/no questions but would include follow-up questions asking for more details if problems are noted (you can see a sample survey here). Similar to Wang and Strong’s user-based DQ framework, these criteria aren’t priorities from writers but rather from users. (Note: In later research, Yoel found that “completeness” might be more important than “relevance.”)

The problem with abstract definitions

These four criteria seem like a solid way to evaluate documentation if you have a way to frequently interact with your users. But even if you could regularly survey your users, these abstract categories don’t provide details about how you might go about making the information more clear, relevant, accurate, and findable.

In other words, these categories are too high-level and general to be more actionable. For example, what does it mean for something to be clear when you consider different audiences and varying technical backgrounds? Is well-written code clear even if doesn’t have comments? The categories fail to specify tactics and tools for executing clarity, relevancy, accuracy, and findability. How do you make something more clear and relevant? What specific steps do you take? So even if you were to get feedback from a user who says that the documentation is not clear, is not relevant, and isn’t easy to understand, it would be difficult to take any specific actions based on this feedback without the user unpacking the detailed reasons for which he or she felt this way.

If you’re not a user (but rather a technical writer) trying to assess documentation through these four questions, the questions are also not helpful. They can’t be fully answered by a non-user. For example, “Could you find the information you needed in the document?” Only the reader can answer this. “Was the information in the document relevant?” Again, only the reader can answer this, not the writer. “Was the information easy to understand?” Again, only the reader can answer this. So while these questions seem like a good approach, I’m not sure how useful they are.

How can we break away from the dependence on user surveys but still develop a method for quality based on the user’s perspective? This is my central question in this section.

Fortunately, if we take the starting categories here (accessibility, accuracy, relevance, clarity), and we are confident that these attributes align with user priorities, then we only need to define how these attributes can be implemented in documentation in specific, concrete, and actionable ways. This is a point Strimling starts to make in So You Think You Know What Your Readers Want?. He says, “In lieu of feedback, what we need is a proven model of how readers actually define documentation quality (DQ), which we can then use to ensure that what we produce is useful to our audience.” The checklist that I’ll define in the next section is a model that identifies specifics from these general qualities.

Other research

Before jumping into the rubric, let’s survey the information quality landscape a bit more, as there are a few other sources worth mentioning. First, Pronovix, a company that specializes in creating developer portals, holds regular Developer Portal Awards. As such, they provide general reasons why they rate some developer portals higher than others. For example, in What is the MVP for a Developer Portal? they write:

We compiled a first list of questions that provides users with the information they might need while working with your API product:

- What is this API?

- How do I get started with this API?

- What do I need to understand about this API?

- How do I get X done with this API?

- Do I know all the details of this API?

- How do I use your API in Y?

- Is somebody still working on this API?

- Where do I go when I have a problem with this API?

- How do I get access to this API?

- Can I afford this API?

- Can I trust this API?

When a user says the documentation is “unclear” or lacks “relevance,” it’s probably because the documentation does not address some of these questions. This is what I mean by being specific about how to make documentation clear without solely relying on survey feedback.

These bullet points are all good questions that one would expect documentation (or a developer portal) to cover. See these articles from Pronovix describing more best practices for documentation and developer portals:

- What goes into an award winning developer portal?

- How to Improve Developer Adoption and Onboarding

- The Best Developer Portals of 2020

Keep in mind that Pronovix’s focus is on developer portals, not standalone API documentation sites (they explain the difference here). As such, they place more emphasis on how users interact both inside and outside the documentation, such as getting API keys from an admin portal, checking service status pages, participating in a community, and more. Since most companies have multiple documentation sites, often aggregated in a portal, I think the emphasis on developer portals is actually more relevant than on documentation alone.

Also, unlike scholarly research, Pronovix looks for best practices and successful patterns in the field, without trying to justify their criteria based on research or from studies that objectively verify and rank these characteristics. Some standards they recommend include API explorers for interactivity, mechanisms to scan and locate reference material, site designs that inspires trust, clear use cases for the API, code samples available in multiple languages, frictionless onboarding, community integration, and more.

Another great resource is Nordic APIs. In 5 Examples of Excellent API Documentation (and Why We Think So), Thomas Bush evaluates 5 documentation sites based on these criteria:

- Authentication guide

- Quickstart guide

- Endpoint definitions

- Code snippets

- Example responses

Bush highlights reasons for admiring certain sites, noting that the lesson with Stripe is “don’t overdo it.” For Twilio, it’s “be beginner-friendly.” For Dropbox, it’s “cater to unique dev backgrounds.” For GitHub, it’s “save developer time wherever you can.” And for Twitter, it’s “be flexible with how you present information.”

Another Nordic API article, 7 Items No API Documentation Can Live Without, discusses 7 essential components in API docs:

- An Authentication Scheme

- HTTP Call Type Definitions

- Endpoint Definitions

- URI Structures, Methods, and Parameters

- Human Readable Method Descriptions

- Requests and Examples

- Expected Responses

In my quality checklist, I’ve listed each of these items but only briefly and generally. Sites like Nordic APIs and Pronovix provide more detailed guidance about how to optimize your documentation in each of these areas.

Technical writing handbooks

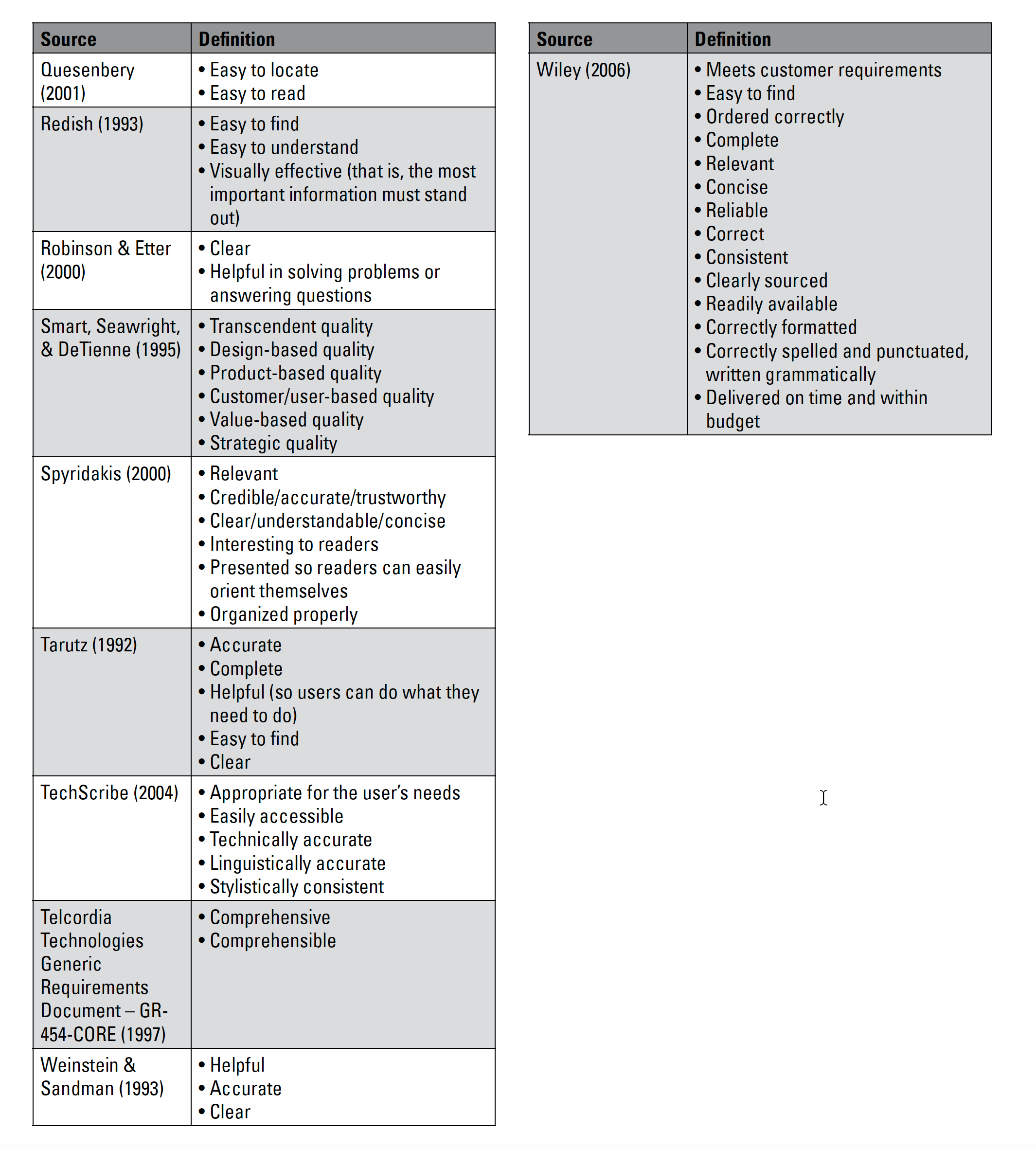

Another place to find quality checklists and guidance for implementing general characteristics like clarity, relevance, accuracy, etc., is in technical writing handbooks. In Developing Quality Technical Information: A Handbook for Writers and Editors, the authors provide a mountain of detail for best practices. They divide their guidelines into these categories and subcategories:

- Easy to use

- Task orientation

- Accuracy

- Completeness

- Easy to understand

- Clarity

- Concreteness

- Style

- Easy to find

- Organization

- Retrievability

- Visual effectiveness

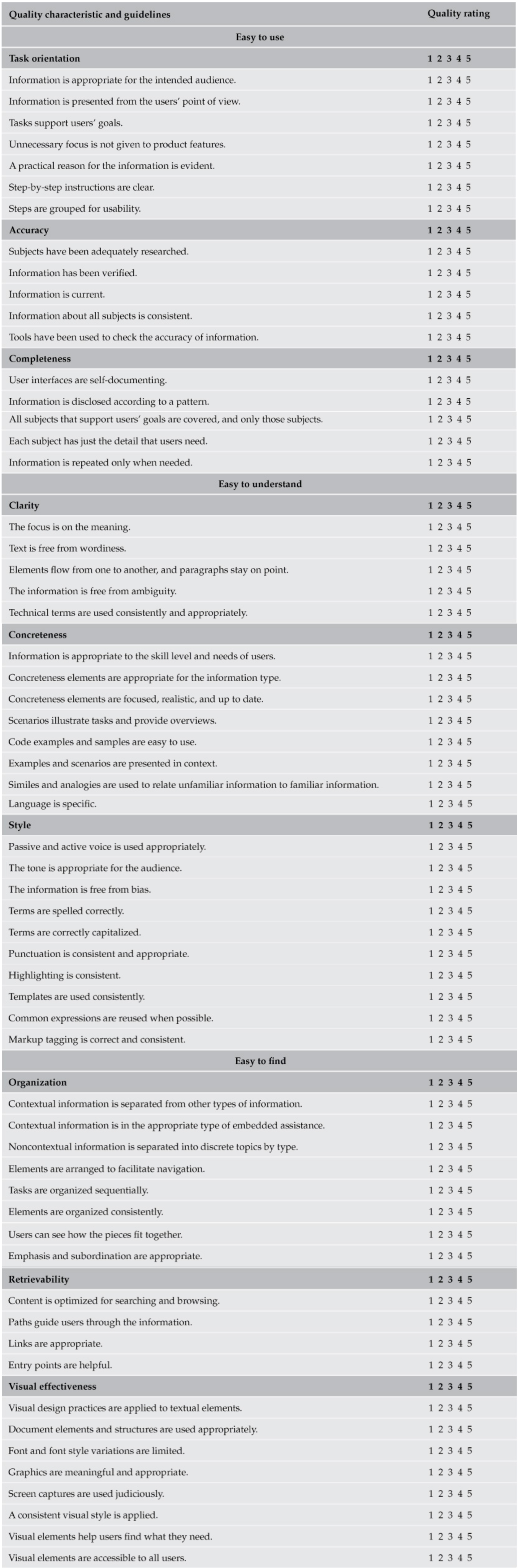

In this model, you might score docs from 1 to 5 depending on how well the docs fulfill each characteristic. The textbook has a lot of examples and detail about how to go about each of these characteristics. There’s even treatment of code samples. Here’s the comprehensive quality checklist provided in the Appendix:

Overall, there are 60 specific characteristics within the various categories. Why not simply adopt this quality checklist? It wouldn’t be a bad approach, for sure. And the principles are so widely held that few would object to them. But I wanted something even more concrete, actionable, and focused on API documentation and developer portals.

Standards specifications

Another place to look at information quality would be standards such as the ASD-STE100. The ASD-STE100 standard was developed by the Aerospace and Defense Industries Association (ASD) to encourage Simplified Technical English (STE). STE consists of a dictionary of about 900 allowed words and a set of 65 writing rules intended to encourage more simplified English.

Another standard is ISO/IEC 26514:2008 - Systems and software engineering — Requirements for designers and developers of user documentation, which is a standard that “specifies the structure, content, and format for user documentation, and also provides informative guidance for user documentation style.”

In the realm of documentation standards, there’s also IEC/IEEE 82079-1 - Preparation Of Information For Use (Instructions For Use) Of Products - Part 1: Principles And General Requirements. Referencing an ISO standard might make your embrace of the standard more defensible. Embracing standards defined here would allow you to benefit from principles already debated, vetted, and finalized. If only the ISO publications were more accessible (e.g., without paywalls), these information resources could be much more valuable.

Another resource developed by SAP and later generalized and adopted by tekom is Standards and Guidelines for API Documentation, by Anne Tarnoruder. You can read a summary of the 68-page book in a tcworld article here: Standardizing API documentation. Tarnoruder emphasizes clear naming guidelines for APIs, noting:

Names are the user interface of APIs. Meaningful, clear, and self-explanatory naming is a key factor in API’s usability and adoption.

Technical writers might work with developers on names to ensure best practices with API design, especially regarding names. I covered some of these principles in my summary of Arnaud Lauret’s book, The Design of Web APIs. However, my focus here is more on documenting an API that has already been finalized rather than providing input on best practices for API design.

Tarnoruder’s book provides comprehensive guidelines for writing the descriptions of API elements in the OpenAPI definition files, illustrated by examples. Tarnoruder also provides templates for REST and OData APIs, if you’re not already using something like OpenAPI. And she provides detailed guidelines for documenting APIs such as Java with Javadoc.

For developer guides, Tarnoruder provides guidelines such as including “conceptual, setup, quick start and how-to information” and avoiding “implementation details irrelevant to users.” This advice is fairly commonplace. However, more interesting, she also encourages writers to address both a code-first learning style and a concepts-first learning style. She writes:

Various usability studies show that API documentation users differ in their learning preferences:

Those with a top-bottom approach would first read all the conceptual topics, and only then start trying the API calls. Those who prefer a bottom-up approach would delve right into code samples to get a quick hands-on experience with the APIs. (Standardizing API documentation)

This is a pattern I described in How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study and is based on research by Michael Meng, Stephanie Steinhardt, and Andreas Schubert in How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study. The authors describe “opportunistic” behavior (people who learn by immediately trying out code and learning by trial and error) versus “systematic” behavior (people who start by carefully reading the manual before acting) as two common patterns of observed usage for developers using documentation. They encourage documentation to accommodate both learning styles.

Other sources for quality

Many other sources can inform documentation quality. For example, the Good Docs project aims to create templates that incorporate best practices. For example, by using the Overview template, you’ll automatically address the various questions and topics needed here. The project has templates for an overviews, quickstarts, reference material, discussions, how-to tasks, logging, tutorials, and more.

Another place to look for information quality is perhaps with information typing models (Information Mapping, DITA, and more). But I’ve already surveyed the landscape sufficiently here. My intent is not to exhaustively survey research on information quality. As Strimling’s earlier research pointed out, most people generally agree on the high-level categories. I want to instead provide specifics on implementation, especially for developer docs.

Continue on to the next section, Quality checklist for API documentation, where I’ll list the details of my information quality checklist for developer docs.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

150/168 pages complete. Only 18 more pages to go.