Processes for reviewing documentation

Conducting a successful documentation review is challenging, especially with developer docs because the content is often highly technical and requires a lot of engineering input and review. At the same time, getting this engineering input and review doesn’t come easy. In this topic, I’ll outline a tactical approach to conducting doc reviews for large amounts of content.

- How to get reviewers to read long content

- Meeting 1: Outline review

- Meeting 2: Questions review

- Create a Slack channel

- Meeting 3: Doc review with the product team

- Meeting 4: Review with field engineers

- Review with support and legal

- Final signoff

- Post-release doc reviews

How to get reviewers to read long content

Getting people to review short amounts of content (one topic or less) isn’t so challenging. What’s challenging is getting engineering types to review dozens of pages. A recent project I worked on had 75 new pages. How exactly do you get engineers, PMs, and others to read and review that many pages, especially in a short amount of time (a few weeks before release)? Long-form reading of tech docs is not usually a characteristic of many people in tech. After 20 minutes, most people want to get back to work. Few will spend all afternoon going through your docs to provide a detailed review.

This puts technical writers in a bind. You end up in a situation where you’re highly dependent on the review and input of others (because the content is so technical or complex), but getting this input is increasingly hard because so few have the patience to read in a careful, meticulous way.

In Processes for managing large documentation projects, I already outlined five general stages of document review:

- Review with doc team

- Review with product team

- Review with field engineers

- Review with legal, support, and other stakeholders

- Review with beta partners

Previously, I didn’t go into detail about more granular processes or the tactical how-to detailing ways to approach these groups, what feedback tools to use, how to prompt action, and so on. In this topic, I’ll dive into these details in a practical, tried-and-true way. Remember that these are tips from a practitioner, based on actual experiences working as a technical writer in the real world doing doc reviews. This approach has worked for me, but also note that each company has a different culture and rhythm, so decide what might work for you in your situation.

Meeting 1: Outline review

In most writing classes, you learn to distinguish between higher-order concerns (e.g., organization, story) before lower-order concerns (e.g., grammar, word choice). The review process uses the same tiered approach. With long content, you want to first be sure that you have the big pieces in place. Draw up an outline of the steps and get the product team to agree on these large pieces and their order.

For example, suppose you identify about 12 steps for implementing a product, and the bulk of the docs are related to this implementation. Get buy-in and approval from the product team for the steps. If you have mini-outlines for each step, even better. In this outline review, the product team doesn’t need to actually read the content. You can talk through the steps and explain the outline at a high level. Once you’ve nailed down these large pieces, start drafting out the details in each topic.

In this phase of the document review, you’re drawing a map of the instructions. You’re not yet blazing the trail (writing the content). For tips about creating workflow maps in docs and why they’re important, see Principle 1: Let users switch between macro and micro views.

Meeting 2: Questions review

As you start drafting the content, no doubt you’ll have many questions about areas you’re unsure about. Especially if you’ve been trying to make the product work for yourself, you should have many questions about issues, unclear points, and other details that you need clarity about. List out about 20 of these questions in a collaborative document (such as Salesforce Quip or Google Docs), and then set up a meeting to ask these questions to the product team. People love to be asked questions, and having a list focuses the meeting on a specific agenda. Again, at this point, you haven’t asked the product team to review any documentation. You’re just asking them to answer questions.

See my article and video titled A tip for doc reviews – bring a list of questions for more details here.

Create a Slack channel

Batching up your questions for a meeting is great, but you will likely have many questions over the life of the project after the meeting. Also, you’ll find that during the meeting, reviewers will have some of the answers, but not all. Maybe questions you asked the product manager and engineering lead during the meeting drew blanks and shrugged shoulders for responses, while they indicated that some other person (e.g., “Sam” or “Sally”) might know. Any sizable project probably has 20+ people working on it, each with different perspectives and specialities. You can’t round them all up each time you have a question.

If your organization has Slack, use it. Create a Slack channel specific to documentation for the project (e.g., acme-tech-docs) and invite people to it. If you ask someone a question they don’t have the answer to, it’s easy for the person to tag another person for the answer, adding them to the channel. Having a dynamic channel like this to ask questions can be incredibly helpful and keep everyone informed about the documentation status.

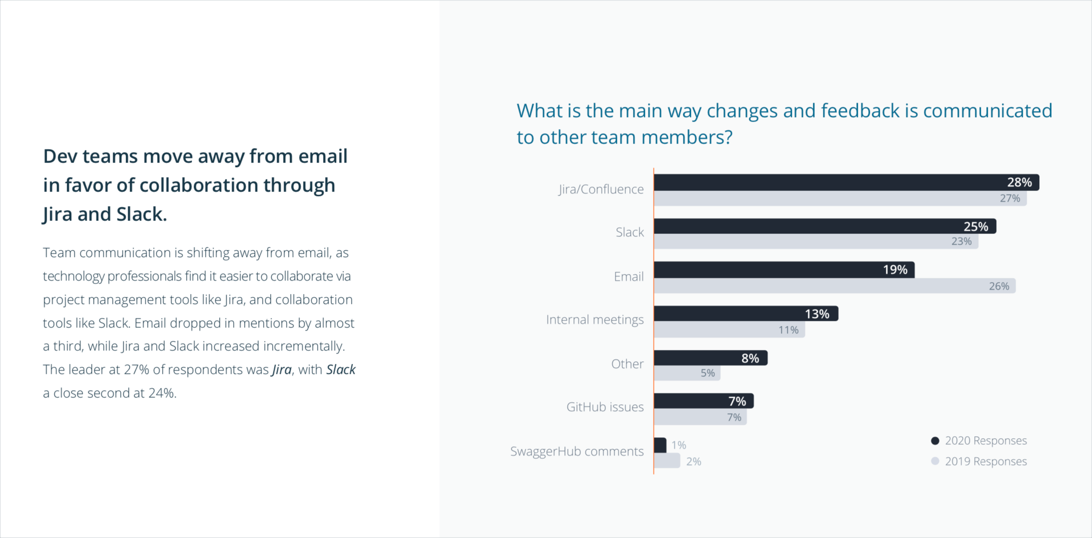

Also, note that Slack is trending as a way for teams to communicate. The SmartBear 2020 API survey found that JIRA and Slack (not email and meetings) are how engineering teams prefer to communicate feedback:

You can read more insights about SmartBear’s 2020 trends in this post: SmartBear’s 2020 API report finds ‘Accurate and detailed documentation’ to be second-most important characteristic of APIs.

Meeting 3: Doc review with the product team

At some point during the content development process, you will have finished a first draft of the documentation. Reaching this point is a huge milestone, so pat yourself on the back. When you finish this first draft, it’s time to formally review the material with the product team to make sure it’s accurate at a foundational level. You’re essentially walking them down the trail you blazed.

The documentation might not be entirely usable or understandable for outsiders to the team (the trail might have many rough spots), but at this point you want to ensure it’s accurate and complete from the product team’s perspective.

It’s helpful to set up a meeting to review this first draft. One technique I’ve learned at Amazon is to dedicate part of the meeting to actually reading through the doc. At Amazon, it’s normal to start meetings by distributing a document that everyone reads for 20 minutes. In Jeff Bezos: This is the ‘smartest thing we ever did’ at Amazon, the author explains:

Jeff Bezos has a nontraditional management style at Amazon, and he says Amazon’s unique twist on meeting structure is the “smartest thing we ever did.”

“Many, many years ago, we outlawed PowerPoint presentations at Amazon,” Bezos said at the Bush Center’s Forum on Leadership in 2018. “And it’s probably the smartest thing we ever did.”

To replace the PowerPoint presentations, Bezos created a new way to hold meetings: Meetings start with each attendee sitting and silently reading a “six-page, narratively-structured memo” for about the first 30 minutes of the meeting.

“[The memo is] supposed to create the context for what will then be a good discussion,” Bezos said.

Although this passage describes business documents (“six-pagers” as they’re called), the same document review culture exists for technical documentation as well. People don’t often feel expected to read documents outside of meetings. It’s not the corporate culture. If you want someone to review something, you set up a meeting and give them time to read the document.

Part of me dislikes this approach because it suggests that people are too lazy/busy to read anything on their own time, and you’re limited to what people can read in 20 minutes (6-10 pages, more or less). But if you’re struggling to get people to read something, this approach works (for about 6 pages). If you have 75 pages to review, you could break up the document review into a series of meetings.

After people finish 20 or so minutes of reading, devote the rest of the meeting to collecting their feedback. You can start with any overall comments and then proceed page by page.

The more executive the reviewer, the more they tend to want to control the meeting and discussion. If I notice this alpha behavior, I usually let the person lead out the discussion rather than forcing them down a predefined path of review topics — assuming the discussion stays focused on documentation.

If you have so many reviewers in different time zones and with different schedules that a focused meeting for the doc review isn’t feasible, or if the documentation is too long to review in one sitting, and you dread setting up 5 meetings to review it, you can encourage the review outside of a meeting. However, you need to set a deadline for collecting feedback. There must be a due date to kick people into action. About the worst thing you can do is send a blanket email to a group asking them to review a lengthy document, without any due dates or commitments to follow up. In Outlook, create an artificial meeting that simply has a due date associated with it as a reminder.

Meeting 4: Review with field engineers

After the product team has reviewed and approved the documentation, incorporate the changes and widen the circle to the next level of reviewers: the field engineers. The “field engineer” role varies from company to company, but if you’re working in developer docs, you probably know which role interfaces with the partners or third-party developers. Who can represent the partner/customer? Who works with partners/customers on a regular basis to implement the company’s products? Maybe it’s an evangelist, a sales engineer, solutions architect, customer experience, technical integrator, etc. Find these people (you should probably already be working with them) and set up a doc review meeting.

In the doc review, you can start by talking through the documentation at a high-level. Then follow the same pattern as before with dedicated meetings to read and review the documentation. Or if it’s not feasible to read the documentation during the meeting, assign them the review as homework with a follow-up due date for feedback. If these field engineers will be guiding partners with this documentation, they are intrinsically motivated to make sure the docs are accurate, clear, and complete. Otherwise, customers/partners will ping them with questions and issues.

To collect feedback from field engineers, try putting your docs on the same collaborative platform for collecting feedback that your company has already established. For example, in many companies, teams use Salesforce Quip or Google Docs as collaboration tools. Both are highly similar, as these tools allow you to annotate text and make comments in the margins, and then reply to the comments. Commenters get notified about replies, and so on. Collaborative tools invite more of a discussion around content, not just a static reading experience. If you can write and edit your docs in a collaborative space, this is ideal.

However, suppose your docs aren’t already in a collaborative space (e.g., maybe they’re already in your authoring system because the project involves a high degree of integration that isn’t feasible to do last minute by copying and pasting from Quip or Google Docs). In this case, you could create a blank page in Quip or Google Docs and invite people to list out questions and issues there, with their initials before their comment. This works well because many times comments apply to the documentation as a whole, or are topics not answered in the documentation.

When a reviewer adds a question, if you follow up with a response, the reviewer will likely add more questions — they learn that you’re listening to their feedback. The reverse is also true. If you don’t respond to questions or comments, reviewers stop leaving them.

If your workplace has another common practice for review, follow it. For example, maybe it’s common that people use track changes in Microsoft Word documents, passing them from one team member to another in a baton-like way. Or maybe everyone uses code review tools to handle comments and doc reviews. Identify the common doc review culture and toolset at your company and plug into it. You’ll have the most success that way. Many documentation systems might have special reviewing features, but if you require people to learn new tools, or worse, to log in to unfamiliar third-party systems, you might not get many people reviewing your docs.

See my post A simple way to write, edit, and publish documentation online using Google Docs and Markdown for stories about the success I had using Google Docs to review content at a former company. See also Matching documentation review practices to company culture.

Review with support and legal

After incorporating the edits from the field engineering review, widen the circle even further to include your support teams, legal team, and any other stakeholders interested in the doc. At this level, the reviewers might not have substantial insights here or technical expertise with the product, but they might need to be aware of it (especially if support will be handling cases about it), and your legal team might need to be involved with any code distribution (sample apps, SDKs, client libraries, etc.). Legal mostly gets involved with your SDK releases. You don’t need to create a meeting for this review, usually. Instead, you can just send these groups a link to the docs and request feedback asynchronously.

At this point, one challenge you might run into is how to deal with all the questions and issues people bring up during the review process. Suppose you end up with dozens and dozens of questions about every possible scenario and fringe case. Adding them into the documentation might make the docs long and verbose. You don’t want to balloon your docs with information that applies to only a small number of cases or partners. Every extra sentence you add dilutes the other sentences.

In these cases, if the question and answer doesn’t logically fit in with the core flow of documentation, consider adding an “Additional Questions” topic (or “FAQ,” if you want to erroneously call it that). Or you can add a section called “Additional information” at the end of the relevant topic. This can be a place where you at least address a question, even if you don’t give more space to it in the regular documentation.

Final signoff

By this time, you should have amassed a significant amount reviewer feedback, and your doc should have gone through multiple iterations and edits. Hopefully, your documentation is nearly ready for release. Now you’re ready for the signoff stage. Identify about five key people who you want to formally sign off on the docs. This might be the product manager, the engineering lead, the manager of field engineers, your legal representative, and the support director. Create a document (maybe a Quip or Google Doc) with their names and an option to select Approve. Send them an email asking for their formal signoff prior to publishing the docs.

This is important: Do not publish the docs until you get their signoff. As a technical writer, you don’t have much leverage to force people to review docs (nevertheless, you’ll be held responsible for any errors or inaccurate information). Your one piece of leverage is to not click the publish button. Especially if you’re working on a new release, many teams are eagerly looking forward to release day. By requiring signoff before you publish the docs, you can force teams to review the content and assume some responsibility. After you click publish, if you failed to get a comprehensive review from key people, they will not likely be incentivized to review documentation post-release. Lack of documentation might not hold up a software release at many companies, but most product teams require documentation as part of their product release. Use your leverage as needed.

Post-release doc reviews

After release, you’re still not done with the documentation. You might have entered a beta period, where beta partners are trying out the docs. Or maybe the docs are entirely public and generally available. Pay attention to the first users and other external feedback. Incorporate a feedback button that allows users to reach out with comments. Also, monitor support channels and forums for feedback.

However, at this stage, you will likely have identified the most significant questions and issues already and addressed them. I’ve found that the best doc reviews happen prior to release, not after. If users have issues, it’s usually with the actual product rather than the documentation. You can’t fix a poorly designed product with great docs — this is why some tech writers tend to gravitate toward product design. (For more on that direction, see Playing a product design role as a content designer – podcast with Jonathon Colman.)

If you have tips for doc reviews, feel free to add them in the comments below.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

140/168 pages complete. Only 28 more pages to go.