SDKs (software development kits)

SDKs (software development kits) and sample apps are similar to code samples and tutorials but are much more extensive and usually involve a whole collection of files that work together as a package or sample app. The SDK might include libraries that you download and incorporate into your application, and can consist of tools, sample apps, and other code.

- What is an SDK?

- What is your role in documenting the SDK and sample app

- Releasing your SDK

- Sample SDKs and sample apps

- Activity with SDKs

What is an SDK?

The terms API and SDK are often used together, but they aren’t synonyms. SDKs implement the language-agnostic REST API in a specific language, such as Java or C++. REST APIs by themselves aren’t tied to any particular language; usually, you demonstrate the APIs by making calls using cURL, a command-line tool for submitting web requests and getting responses. But developers won’t use cURL requests when they implement your API. Instead, they will implement the API requests using the language their application is coded in.

For example, Python, C++, or Node applications make API requests in different ways. Each language has its own way of constructing requests to a web API. You can use Postman or Paw to auto-generate a simple request in a specific language (see Auto-generating code samples). However, the SDK takes the implementation to another level. SDKs might involve many more files or libraries as part of the implementation.

In What is the Difference Between an API and an SDK?, Kristopher Sandoval explains an SDK as follows:

SDK stands for “Software Development Kit”, which is a great way to think about it — a kit. Think about putting together a model car or plane. When constructing this model, a whole kit of items is needed, including the kit pieces themselves, the tools needed to put them together, assembly instructions, and so forth.

An SDK or devkit functions in much the same way, providing a set of tools, libraries, relevant documentation, code samples, processes, and or guides that allow developers to create software applications on a specific platform. If an API is a set of building blocks that allows for the creation of something, an SDK is a full-fledged workshop, facilitating creation far outside the scopes of what an API would allow.

Sandoval compares examples from both Facebook APIs and SDKs to clarify the difference. He sums up the difference as follows: “The SDK is the building blocks of the application, whereas the API is the language of its requests.” In other words, the SDK provides all the necessary code you would need to build an application that uses the API.

What is your role in documenting the SDK and sample app

In the SwaggerHub tutorial, I showed how to auto-generate client SDKs through SwaggerHub’s interface. But usually rather than relying on auto-generated SDKs, if your development team offers a client SDK, it will be code that the development team prepares and tests. The development team often provides the SDK in a few target languages based on their user’s main language, making it easier for users to implement the API.

As an API technical writer, documenting SDKs and sample apps presents a tough challenge because SDKs require you to be familiar with one or more programming languages. I explore the question of how much code you need to know in the Jobs section, so I won’t get into too much detail here. Usually, engineers don’t expect you to know multiple programming languages in depth, but some familiarity with them will be required in order to both write and review the documentation. When deciding whether to call a block of code a function, class, method, or another name, you need to have a basic understanding of the terms used in that language.

If you’re unfamiliar with the language, you can just take what engineers write, clean it up a bit, try to walk through the steps to get any sample apps working and see what feedback you get from users. Usually, if you can get a sample app installed and working, and make sure that the basic documentation for running the app works, as well as what the app does, that might be sufficient. But of course, making any significant contributions to SDK documentation will require you to be familiar with that programming language.

As I mentioned in the Code samples and tutorials, you don’t need to document how a particular language works, just how your own company’s SDK works. Presumably, if an engineer downloads the Java SDK for an API, it’s because the engineer is already familiar with Java. However, if your API was implemented in a particular way in Java, you should explain why that approach was taken. (Granted, understanding the difference between documenting Java and documenting a particular approach in the Java implementation also requires you to understand Java.)

Releasing your SDK

When you release the SDK, although engineers might handle the release, they will probably look to you for input on SDK readiness, including preparation of the Readme, documentation, licensing, and other details. See Processes for managing SDK release processes for more information about these details.

Sample SDKs and sample apps

The following examples show documentation for some sample SDKs and sample apps.

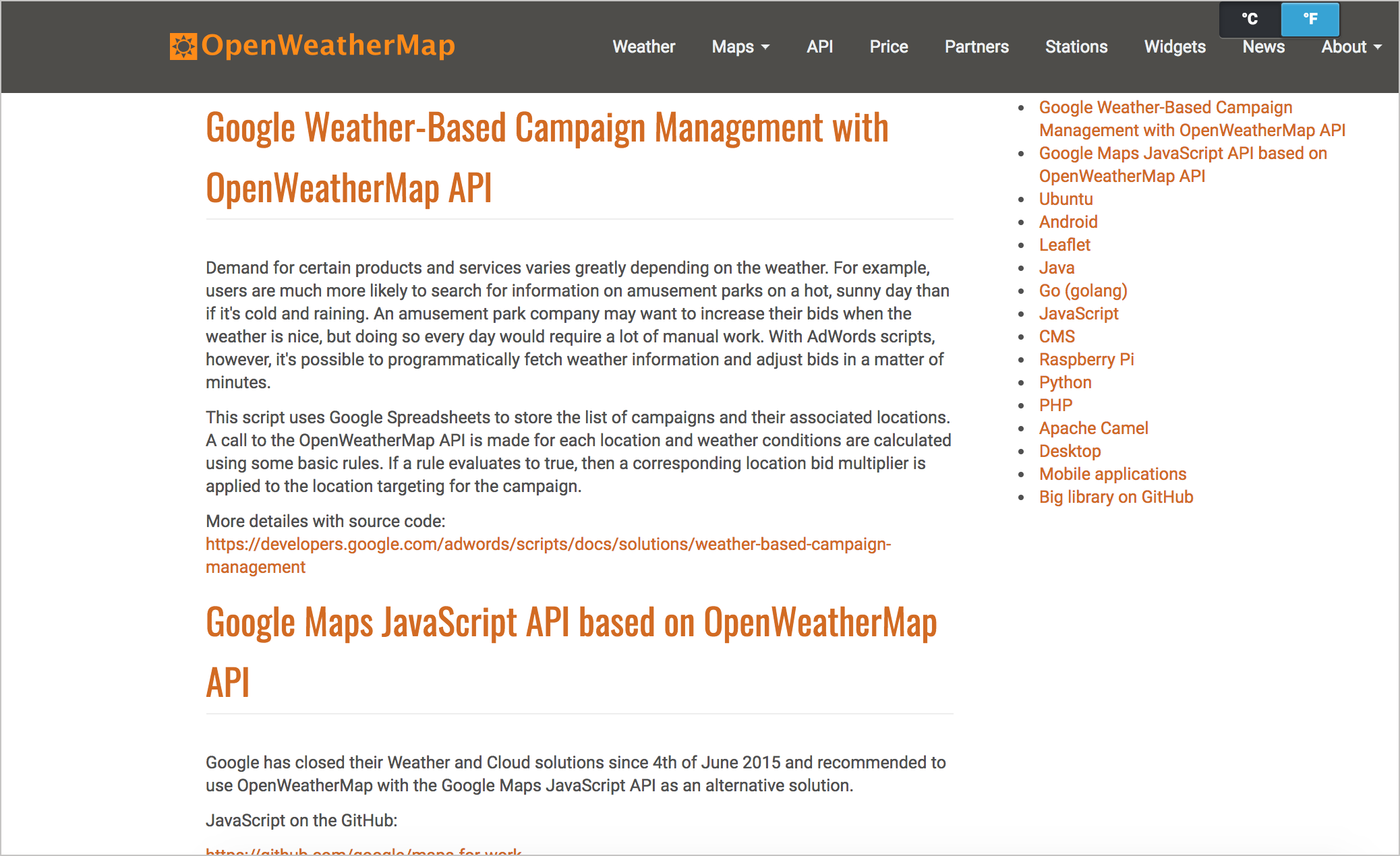

OpenWeatherMap API

The example integrations for the OpenWeatherMap API aren’t just short code snippets that show how to call an endpoint. Instead, they are full-fledged, sophisticated integrations across a variety of platforms. As such, many of the code samples are stored in GitHub. Each scenario has a detailed explanation.

If you can put your sample apps and SDKs on GitHub, it’s usually a good idea to do so. Storing code on GitHub accomplishes two purposes: First, it usually puts the burden on engineering to maintain and test the code samples as well as respond to issues users might log against the project. Second, it makes it easier to provide fully functional code, since users can clone the project and start working with it immediately. The development team can also push out updates easily.

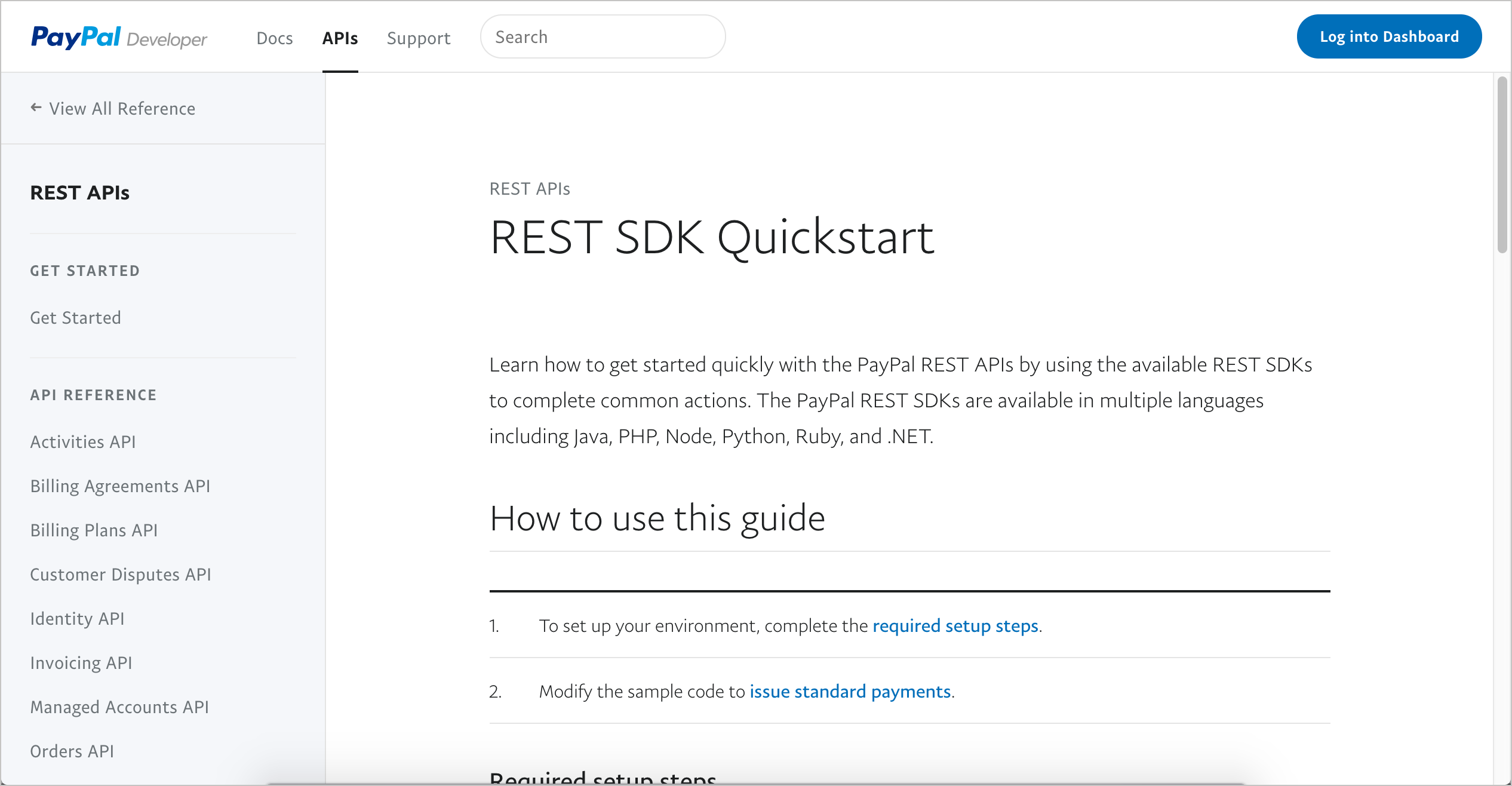

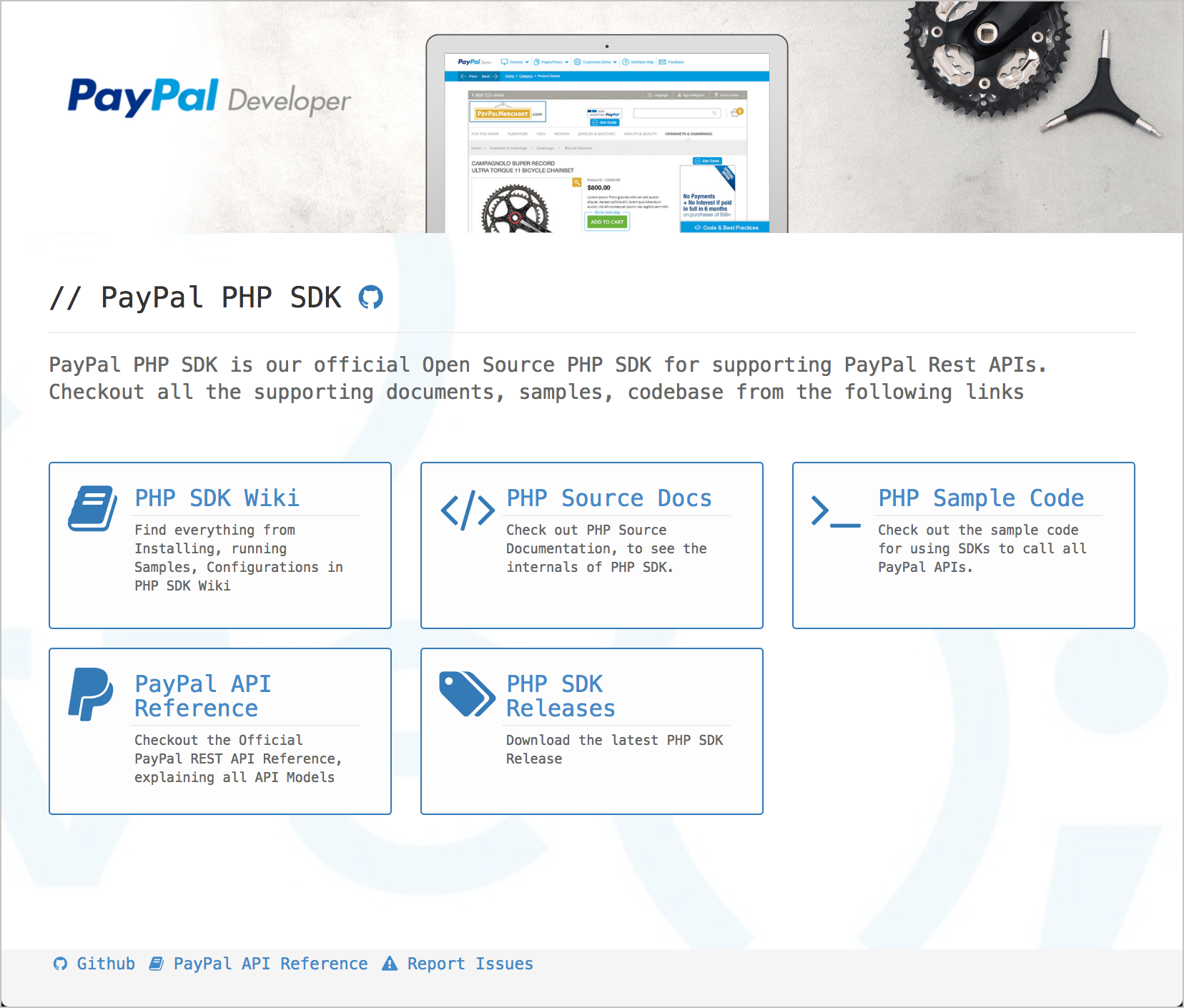

Paypal REST SDK

The SDKs in the Paypal’s Additional information section include Node JS, PHP, Python, Ruby, Java, and .NET SDKs. Each implementation has its own GitHub site, with its own wiki, sample code, source docs, and more. If you browse some of these GitHub pages (such as the site for PHP), you can see the whole collection of language-specific files for this SDK. These sites show how SDKs include a variety of file types.

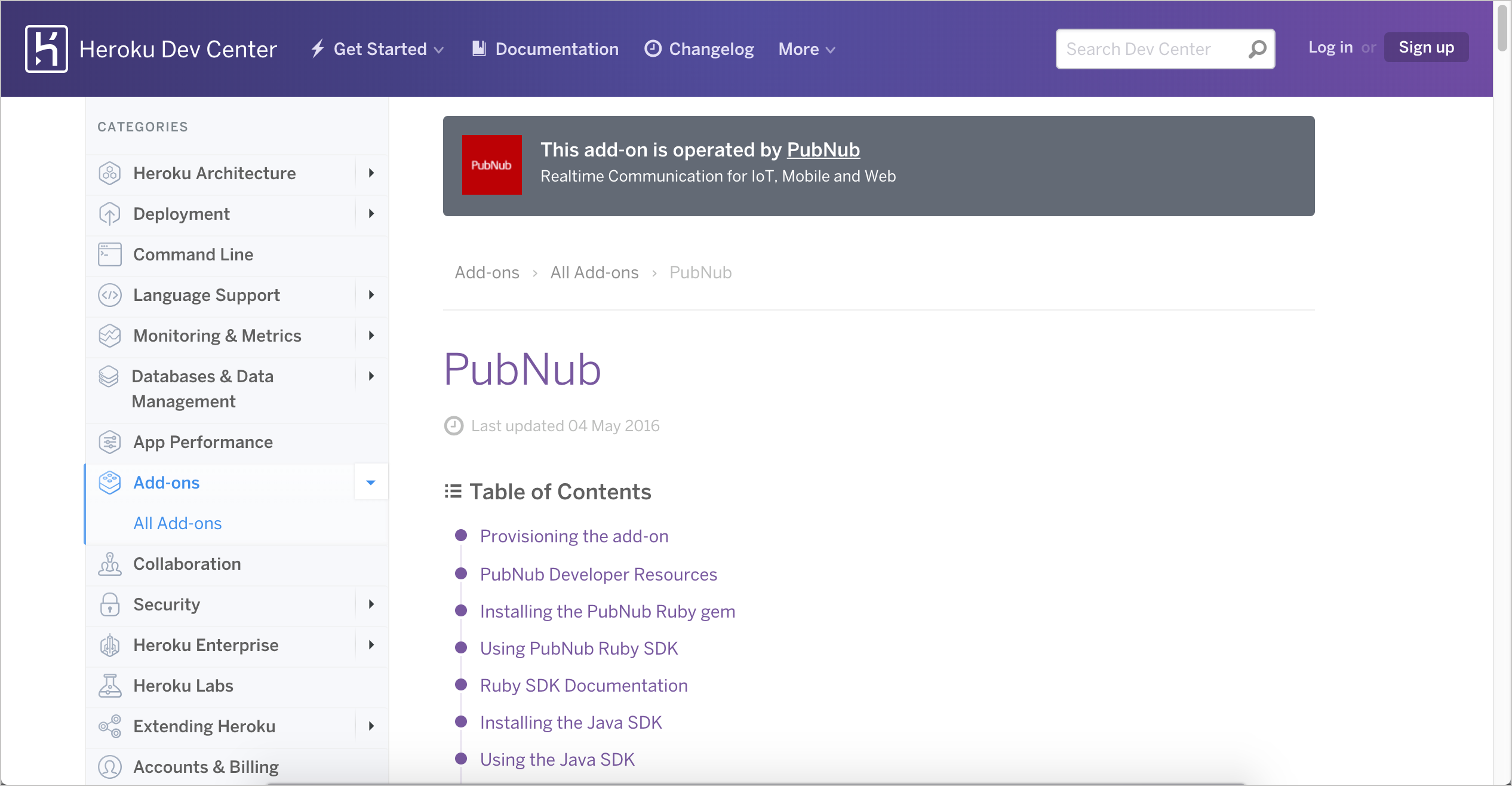

Heroku SDK

The Heroku SDK is actually operated by PubNub and includes a Ruby, Java, Node JS, Python, and PHP SDK. If you look at, for example, the Python SDK documentation, you see links to Getting Started, Tutorials, and API reference.

As I mentioned earlier, it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to contribute significantly to either writing or reviewing the SDK documentation unless you’re somewhat familiar with the language. Development groups usually don’t expect technical writers to be conversant in half a dozen languages. More likely, you’ll be reliant on engineers who are conversant in these languages and frameworks to author this content. But doing so will require you to interact skillfully with engineers and be somewhat familiar with programming jargon and concepts.

If engineers tell you that users should know X, don’t just submit to their judgment out of ignorance with the language. Instead, find some developers in that language (even internal engineers in other groups) to test the documentation against. If those users push back and say they need more detail, you can interface with the engineering team to provide it.

Without more familiarity with the language of the SDK, technical writers act more as mediators between the engineering authors and the engineering users. Technical writers identify and fill gaps in the documentation, and they often manage the publishing and distribution of the docs. But the content itself might be too technical for most technical writers to play a content authoring role. (I explored this topic in depth in an essay in my Simplifying Complexity series called Be both a generalist and specialist through your technical acuity.)

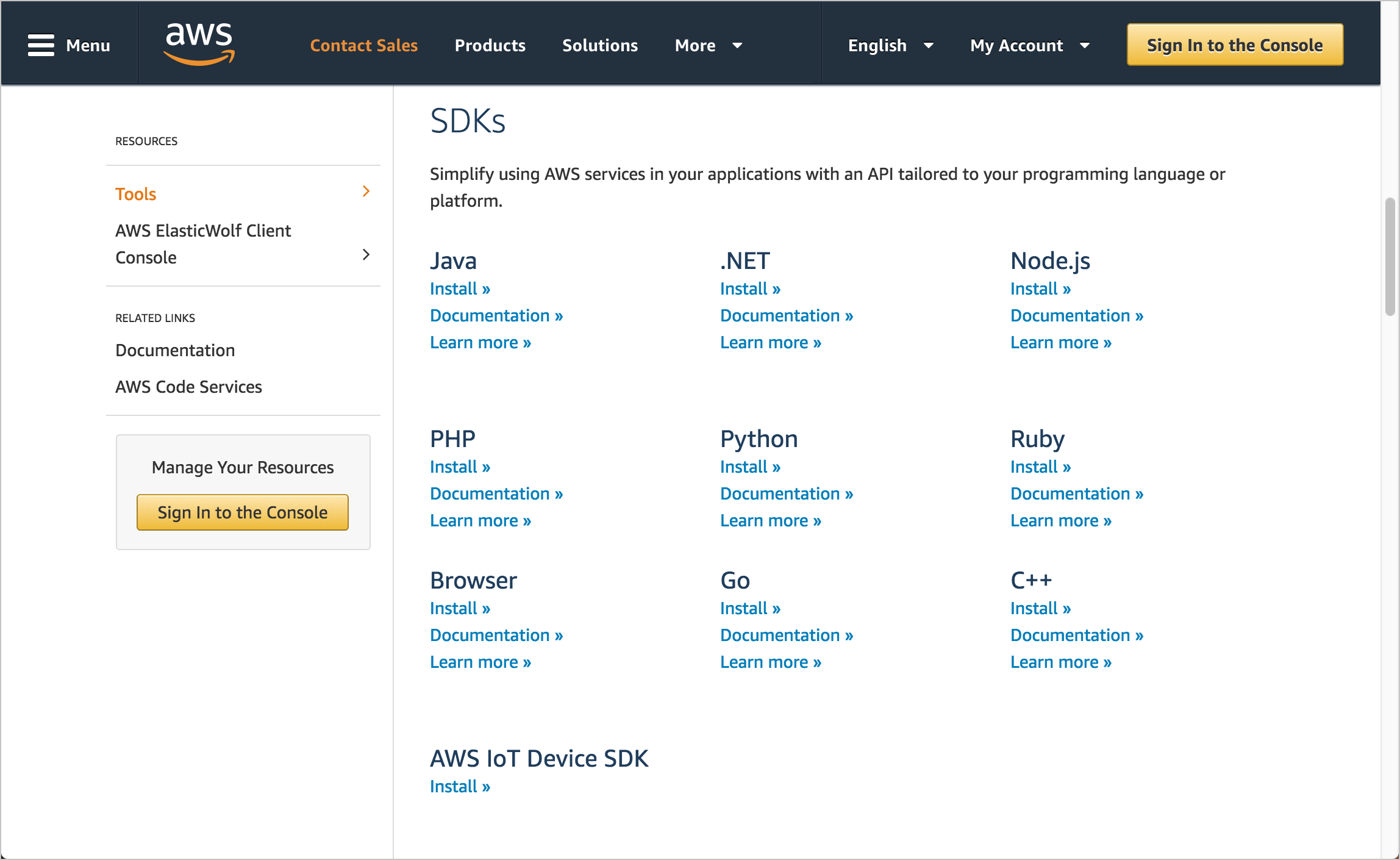

Amazon SDK

One notable characteristic of the AWS docs is their consistency from doc set to doc set. The consistency leads to predictability and hence usability. However, in the SDK docs, you can see that different document generators are used to generate the docs for the various libraries. If you look at the API references for each of these SDK libraries, you’ll see a C++ document generator for C++ SDK docs, a Ruby document generator for Ruby SDK docs, a PHP document generator for PHP SDK, a .NET document generator for .NET SDK docs, a Java document generator for Java SDK docs and so on.

Each programming language typically has its own unique annotation syntax and document generation tools. The annotation syntax (which programmers use directly in the code — see Javadoc tags for an example of Javadoc tags) differs by language and tool but is mostly similar. Because the documentation is generated from annotations in the code, engineers usually write and maintain this documentation. (Having engineers write and maintain it also reduces documentation drift.)

Even so, there is probably quite a bit of variability from one library to the next. How do engineers ensure they use the same description for a class in Java that they do for Ruby and PHP? These document generator tools aren’t usually smart enough to leverage snippets or includes stored in a shared online repository. You also can’t usually use variables or other single-sourcing techniques. As a result, there might be a lot of variation from one SDK’s documentation to another for mostly the same concepts.

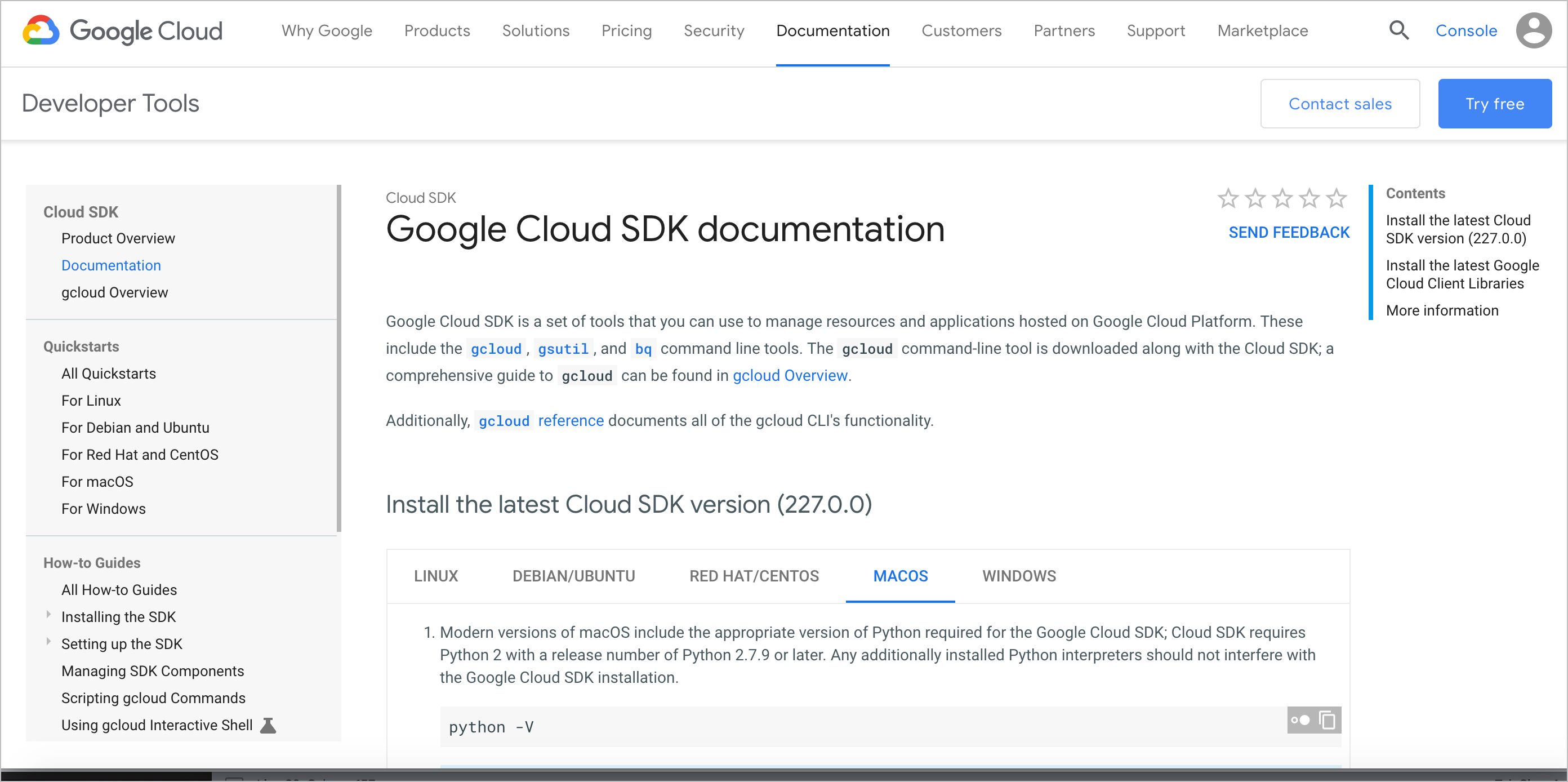

Google Cloud SDK

The Google Cloud SDK provides quickstart guides for Linux, Debian, Ubuntu, and other operating systems. The guides explain how to install, set up, and manage the SDK commands. An API reference for the commands is also included.

Looking at the Google Cloud SDK versus the Amazon SDK shows some of the breadth and variety of technologies you might have to document in SDK territory. These SDKs are specific to a particular programming language, operating system, or another framework, and as such, it can be daunting to try to ramp up to document this category of tools. For SDK documentation, you’ll need to work closely with engineers and listen to feedback from users.

Activity with SDKs

With the open-source project you identified, identify the information about any SDKs for the API. Answer the following questions:

- Does the API project include any SDKs?

- In what languages are the SDKs provided?

- Why did the developers choose to make the SDK available in that particular language?

- How extensive are the instructions for working with that SDK?

- Where is the code for the SDK stored and delivered? In GitHub? In a separate downloadable zip file?

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

87/168 pages complete. Only 81 more pages to go.