Working in YAML (OpenAPI tutorial)

Before we dive into the steps of the OpenAPI Tutorial, it will help to have a better grounding in YAML, since this is the most common syntax for the OpenAPI specification document. (You can also use JSON, but the prevailing trend with the OpenAPI document format is YAML.)

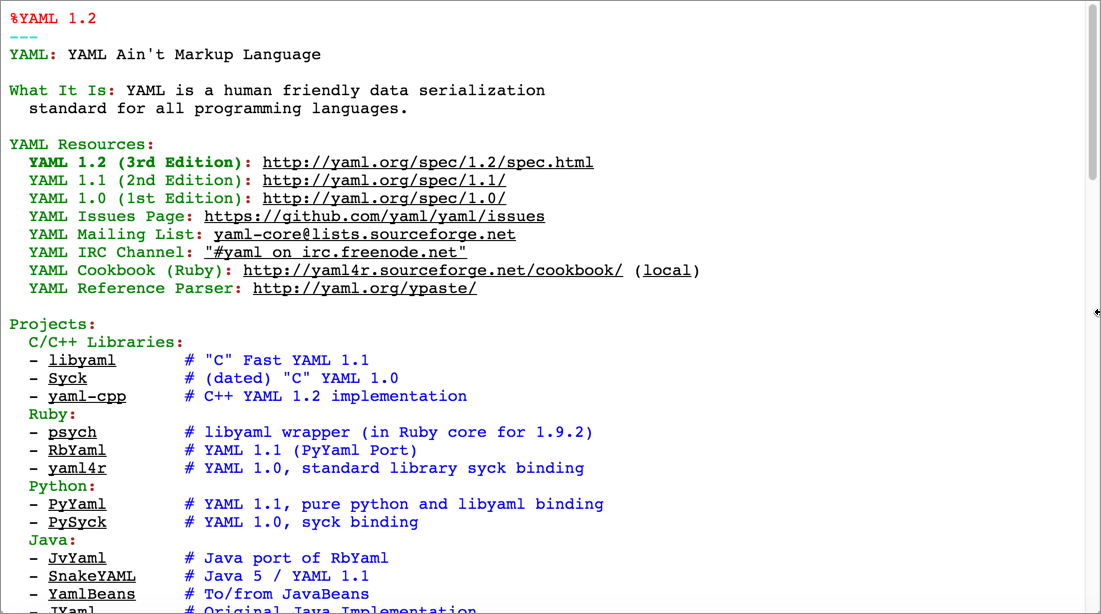

YAML stands for “YAML Ain’t Markup Language.” This means that the YAML syntax doesn’t have markup tags such as < or >. Instead, it uses colons to denote an object’s properties and hyphens to denote an array.

- Working with YAML

- YAML is a superset of JSON

- YAML syntax

- Comparing JSON to YAML

- Some features of YAML not present in JSON

- JSON versus YAML for the spec format

- Review and summary

- Let’s get started

Working with YAML

YAML is easier to work with because it removes the brackets, curly braces, and commas that get in the way of reading content.

YAML is an attempt to create a more human-readable data exchange format. It’s similar to JSON (which is actually a subset of YAML) but uses spaces, colons, and hyphens to indicate the structure.

Many computers ingest data in a YAML or JSON format. It’s a syntax commonly used in configuration files and an increasing number of platforms, so it’s a good idea to become familiar with it.

YAML is a superset of JSON

For the most part, YAML and JSON are different ways of structuring the same data. Dot notation accesses the values the same way. For example, the Swagger UI can read the openapi.json or openapi.yaml files equivalently. Pretty much any parser that reads JSON will also read YAML. However, some JSON parsers might not read YAML because there are a few features YAML has that JSON lacks (more on that below).

YAML syntax

With a YAML file, spacing is significant. Each two-space indent represents a new level:

level1:

level2:

level3:

Each new level is an object. In this example, the level1 object contains the level2 object, which contains the level3 object.

With YAML, you generally don’t use tabs (since tab spacing is non-standard). Instead, you space twice.

Each level can contain either a single key-value pair (also referred to as a mapping in YAML lingo) or a sequence (a list of items preceded by hyphens):

level3:

-

itema: "one"

itemameta: "two"

-

itemb: "three"

itembmeta: "four"

The values for each key can optionally be enclosed in quotation marks. If your value has a colon or quotation mark in it, enclose it in quotation marks.

Comparing JSON to YAML

Earlier in the course, we looked at various JSON structures involving objects and arrays. So let’s look at the equivalent YAML syntax for each of these same JSON objects.

You can use Unserialize.me to make the conversion from JSON to YAML or YAML to JSON.

Here are some key-value pairs in JSON:

{

"key1":"value1",

"key2":"value2"

}

Here’s the same structure expressed in YAML syntax:

key1: value1

key2: value2

Here’s an array (list of items) in JSON:

["first", "second", "third"]

In YAML, the array is formatted as a list with hyphens:

- first

- second

- third

Here’s an object containing an array in JSON:

{

"children": ["Avery","Callie","lucy","Molly"],

"hobbies": ["swimming","biking","drawing","horseplaying"]

}

Here’s the same object with an array in YAML:

children:

- Avery

- Callie

- lucy

- Molly

hobbies:

- swimming

- biking

- drawing

- horseplaying

Here’s an array containing objects in JSON:

[

{

"name":"Tom",

"age":43

},

{

"name":"Shannon",

"age":41

}

]

Here’s the same array containing objects converted to YAML:

-

name: Tom

age: 43

-

name: Shannon

age: 41

Hopefully, by seeing the syntax side by side, it will begin to make more sense. Is the YAML syntax more readable? It might be difficult to see in these simple examples, but generally it is.

JavaScript uses the same dot notation techniques to access the values in YAML as it does in JSON. (They’re pretty much interchangeable formats.) The benefit to using YAML, however, is that it’s more readable than JSON.

However, YAML might be more tricky because it depends on getting the spacing just right. Sometimes that spacing is hard to see (especially with a complex structure), and that’s where JSON (while maybe more cumbersome) is perhaps easier to troubleshoot.

Some features of YAML not present in JSON

YAML has some features that JSON lacks. You can add comments in YAML files using the # sign. YAML also allows you to use something called “anchors.” For example, suppose you have two definitions that are similar. You could write the definition once and use a pointer to refer to both:

api: &apidef Application programming interface

application_programming_interface: *apidef

If you access the value, the same definition will be used for both. The *apidef acts as an anchor or pointer to the definition established at &apidef.

You won’t use these unique YAML features in the OpenAPI tutorial, but they’re worth noting because JSON and YAML aren’t entirely equivalent. For details on other differences between JSON and YAML, see Learn YAML in Minutes. To learn more about YAML, see this YAML tutorial.

YAML is also used with Jekyll. See my YAML tutorial in the context of Jekyll for more details.

JSON versus YAML for the spec format

Let’s clear up some additional details around JSON and YAML in the context of the OpenAPI specification. The specification document in my OpenAPI tutorial uses YAML, but it could also be expressed in JSON. JSON is a subset of YAML, so the two are practically interchangeable formats (for the data structures we’re using). Ultimately, though, the OpenAPI spec is a JSON object. The specification notes:

An OpenAPI document that conforms to the OpenAPI Specification is itself a JSON object, which may be represented either in JSON or YAML format. (See Format)

In other words, the OpenAPI document you create is a JSON object, but you have the option of expressing the JSON using either JSON or YAML syntax. YAML is more readable and is a more common format (see API Handyman’s take on JSON vs YAML for more discussion), so I’ve used YAML exclusively in code samples here. You will see that the OpenAPI specification documentation on GitHub always shows both the JSON and YAML syntax when showing specification formats. (For a more detailed comparison of YAML versus JSON, see “Relation to JSON” in the YAML spec.)

YAML refers to data structures with three main terms: “mappings (hashes/dictionaries), sequences (arrays/lists) and scalars (strings/numbers)” (see “Introduction” in YAML 1.2). However, because the OpenAPI spec is a JSON object, it uses JSON terminology — such as “objects,” “arrays,” “properties,” “fields,” and so forth. As such, I’ll be showing YAML-formatted content but describing it using JSON terminology.

Review and summary

So that we’re on the same page with terms in the upcoming tutorial, let’s briefly review. Each level in YAML (defined by a two-space indent) is an object. In the following code, california is an object. animal, flower, and bird are properties of the california object.

california:

animal: Grizzly Bear

flower: Poppy

bird: Quail

Here’s what this looks like in JSON:

{

"california": {

"animal": "Grizzly Bear",

"flower": "Poppy",

"bird": "Quail"

}

}

The specification often uses the term “field” in the titles and table column names when listing the properties for a specific object. (Further, it identifies two types of fields — “fixed” fields are declared, unique names while “patterned” fields are regex expressions.) Fields and properties are used synonymously in the OpenAPI spec.

In the following code, countries contains an object called united_states, which contains an object called california, which contains several properties with string values:

countries:

united_states:

california:

animal: Grizzly Bear

flower: Poppy

bird: Quail

In the following code, demographics is an object that contains an array:

demographics:

- population

- land

- rivers

Here’s what the above code looks like in JSON:

{

"demographics": [

"population",

"land",

"rivers"

]

}

Hopefully, those brief examples will help align us with the terminology used in the tutorial.

Let’s get started

With that information about YAML, hopefully the upcoming step-by-step sections that walk through each section in the OpenAPI spec, using YAML as the primary format, will make more sense. Let’s get started with Step 1: The openapi object (OpenAPI tutorial).

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

51/168 pages complete. Only 117 more pages to go.